- SPEECH

Introductory statement

Speech by Andrea Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the press conference on the results of the 2021 SREP cycle

Frankfurt am Main, 10 February 2022

Jump to the transcript of the questions and answersWelcome to our press conference on the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process – SREP for short.

For the 2020 SREP cycle, we adopted a pragmatic approach given the outbreak of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. We focused on how banks were handling the challenges arising from the crisis and kept most Pillar 2 requirements (P2R) and Pillar 2 guidance (P2G) stable.

In 2021 we returned to a full SREP assessment. I will outline the results by concentrating on four main topics. First, the resilience that banks have shown. Second, the risks that could still materialise from the COVID-19 fallout. Third, the structural challenges which predate the pandemic but continue to weigh on banks. And fourth, risks that are still emerging but already require immediate action.

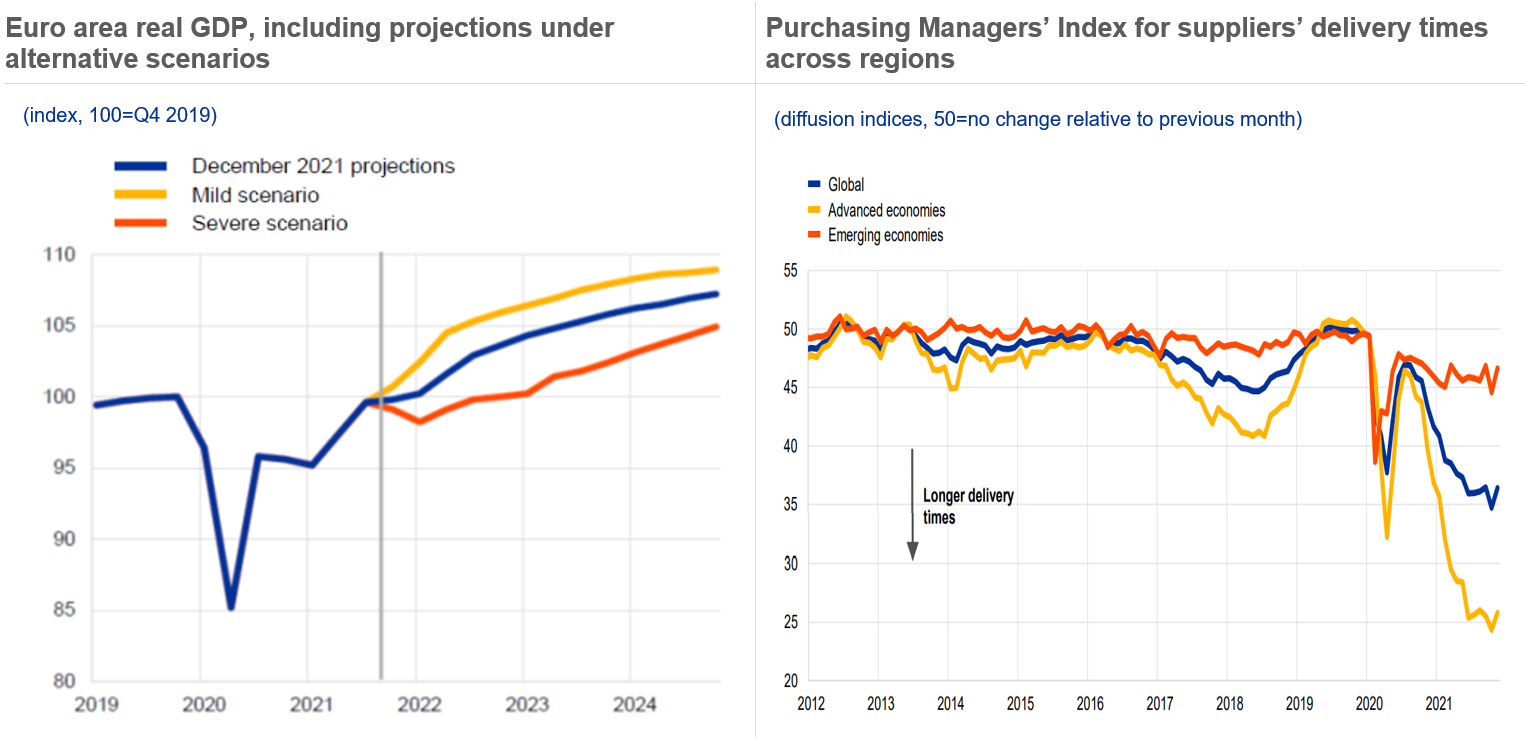

A resilient banking sector navigating through an uncertain macroeconomic environment

When I spoke at last year’s press conference, economic forecasts projected that output would return to pre-pandemic levels in mid-2022, following the record drop in activity during the first phase of the pandemic. Thankfully, the recovery was even faster than expected. Output has already rebounded to pre-pandemic levels, and economic growth is projected to remain strong over the next three years. But there is still uncertainty about how the pandemic will evolve, mostly owing to the potential spread of new virus variants, and supply chain disruptions are weighing on trade and overall economic activity.

Chart 1

The euro area economy is continuing to recover, but the evolution of the pandemic and supply bottlenecks are weighing on the outlook …

Source left-hand chart: December 2021 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area.

Note left-hand chart: The vertical line marks the start of the projection horizon.

Source right-hand chart: ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 8, 2021.

Notes right-hand chart: The global Purchasing Managers’ Index for suppliers’ delivery times quantifies developments in the time required for the delivery of inputs to firms and captures capacity constraints of a different nature (e.g. intermediate goods shortages, transportation delays or labour supply shortages). The latest observations are for November 2021.

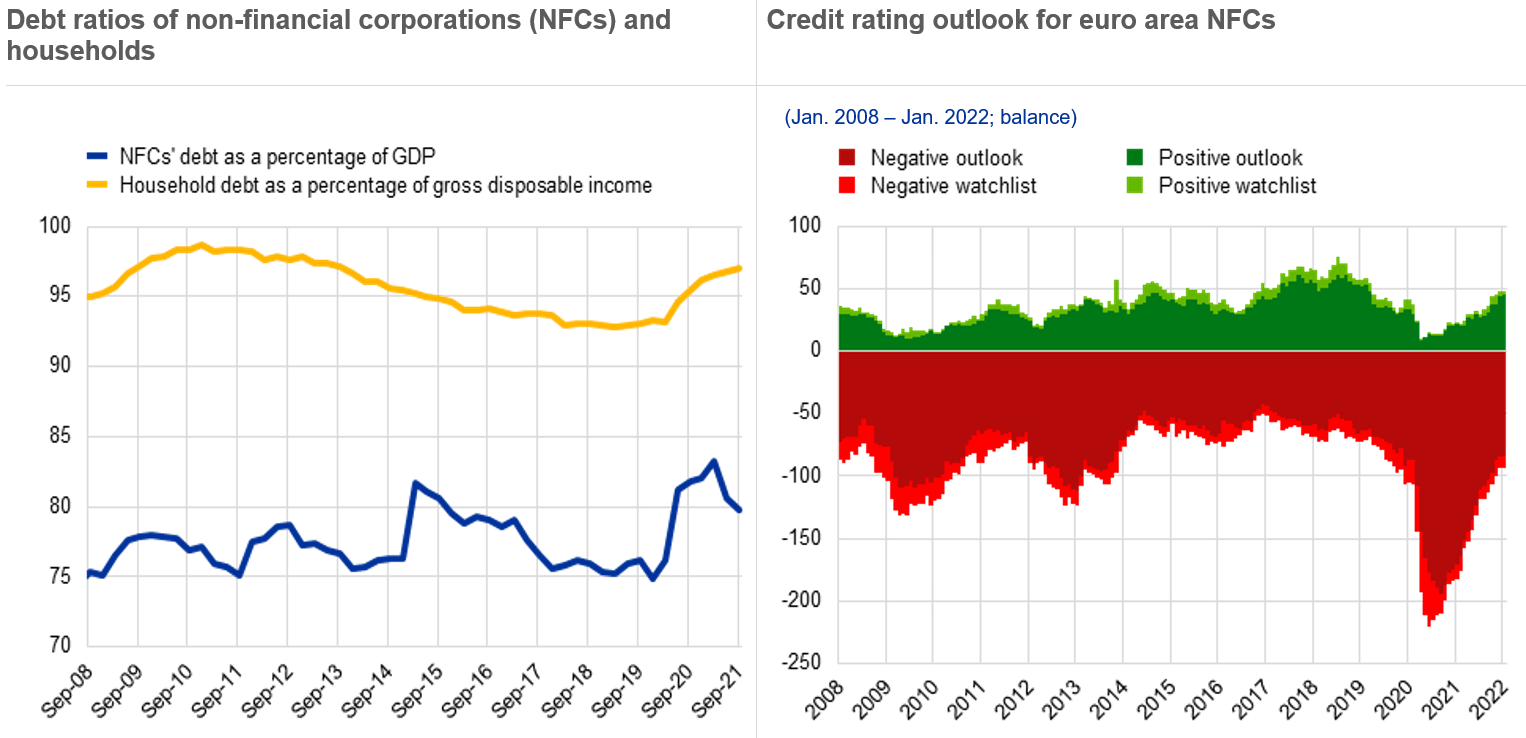

While the macroeconomic outlook has brightened during the past year, elevated levels of private sector debt and the risk of credit rating downgrades leave households and firms in a potentially vulnerable position.

Chart 2

... highlighting potential medium-term vulnerabilities stemming from high private sector indebtedness and future challenges

Sources left-hand chart: Eurostat and ECB.

Note left-hand chart: The latest observations are for September 2021.

Sources right-hand chart: S&P and ECB calculations.

Note right-hand chart: This chart shows stocks of positive/negative outlooks and watchlists for S&P ratings of NFCs domiciled in the euro area. The number of negative outlook and watchlist ratings is inverted. The latest observations are for 1 January 2022.

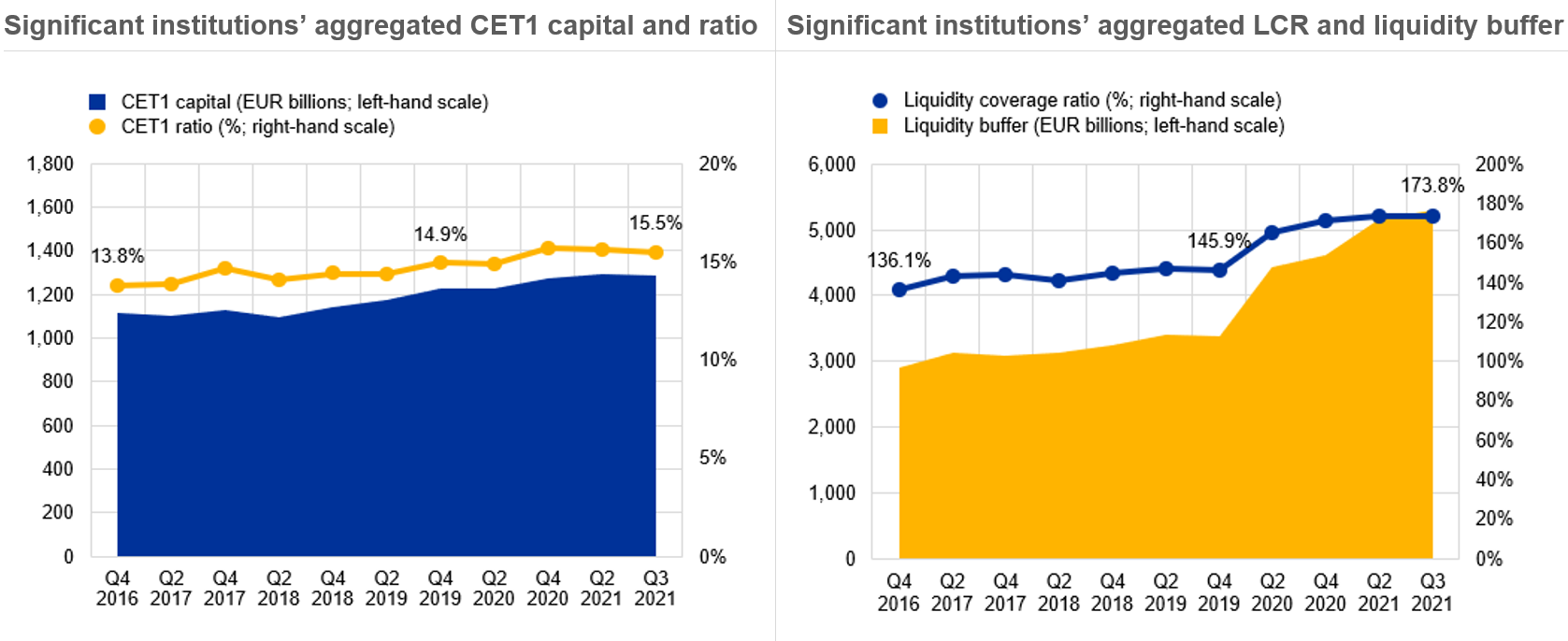

This makes it all the more crucial for European banks to have ample capital and liquidity positions. After all, these allow banks to protect themselves in the event that firms or households have difficulties servicing their loans. Fortunately, capital and liquidity ratios have not only avoided a hit during the pandemic, they are actually higher now than they were when the first pandemic-related restrictions were put in place.

Chart 3

Significant institutions have maintained solid capital and liquidity positions

Source: Supervisory reporting.

Notes: The sample for Q3 2021 comprises 113 SIs. The number of SIs can change from one reference period to another owing to amendments to the list of SIs following assessments by ECB Banking Supervision.

Note left-hand chart: The chart shows the transitional CET1 ratio.

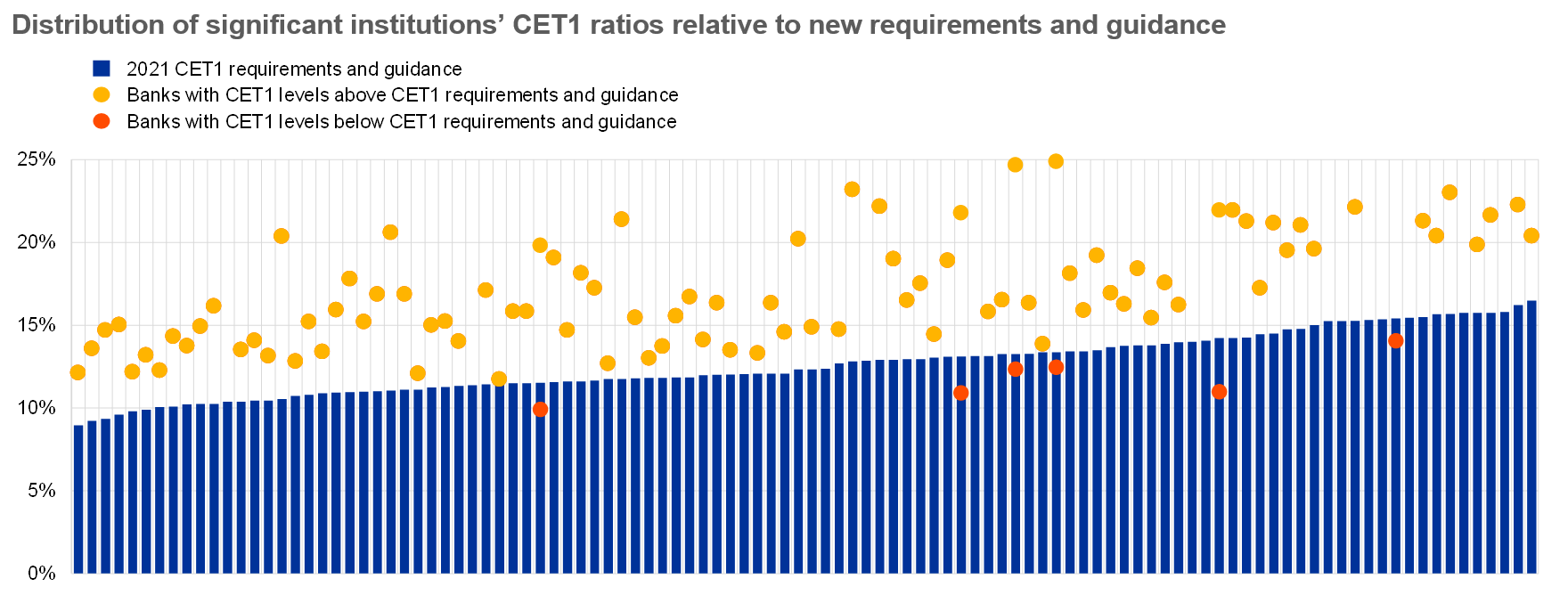

Only a handful of the banks under our supervision operate at capital levels below those set by the CET 1 overall capital requirement and guidance, with two instances of breach of the combined buffer requirement (at total capital level). In all cases, the use of buffers seems to have been driven by longstanding structural issues rather than by the impact of the pandemic.

The ample capital headroom and the rebound in profitability in 2021 also brought distribution plans back to pre-pandemic levels, with banks increasingly relying on share buy-backs to release part of the payments that were frozen during the first stages of the pandemic. This had a positive impact on banks’ valuations. Our supervisors closely scrutinise distribution plans, focusing on the robustness and reliability of banks’ capital projections.

When the first wave of the pandemic hit, we helped banks to absorb losses and continue lending by taking a series of extraordinary capital and liquidity measures. We asked banks to limit distributions but allowed them to dip into their liquidity and capital buffers. In September 2020, to make it easier for banks to implement the extraordinary monetary policy support, we also granted partial relief from the leverage ratio requirement, allowing banks to exclude certain central bank exposures from the calculation of their required capital.

In 2021 the gradual improvement in macroeconomic conditions, the results of the stress tests, and our assessment of banks’ individual capital plans prompted us to take concrete steps on the path to normality. We lifted our dividend recommendation as of last September and in December we confirmed that the relief from the liquidity coverage ratio would not continue into 2022. Given the ample capital headroom banks have at their disposal, we can today confirm the exit plan from the remaining support measures. From 1 January 2023 the ECB will expect banks to operate above their overall capital requirements and Pillar 2 guidance. And after March 2022 we will no longer allow any exemptions from the calculation of the leverage ratio.

Chart 4

The vast majority of significant institutions have CET1 ratios that go beyond the new requirements and guidance, with very few exceptions

Sources: CET1 requirements and guidance include P2Rs/P2G based on 108 SREP decisions applicable as at Q1 2022, as well as any AT1/T2 shortfalls that need to be covered with CET1; CET1 ratios are as at Q3 2021; systemic buffers (G-SII, O-SII and systemic risk buffers) and countercyclical capital buffers are as at Q1 2022.

Key findings and results of the 2021 SREP exercise

In the 2021 SREP cycle we not only zoomed in on risks to credit quality stemming from the pandemic, we also looked at aspects related to the legacy stock of non-performing exposures (NPEs), as our supervisory expectations on the provisioning for NPEs became applicable. To cater for any shortfalls in provisions relative to those expectations, we introduced a targeted Pillar 2 requirement add-on. We were pleased to see how banks responded to this policy and our draft SREP decisions, with several booking additional provisions or capital deductions and making additional NPE transfers until the last quarter of 2021. The aggregate shortfall in NPE provisions decreased by over 75% during the year, leaving only a small number of banks subject to fairly low add-ons in our final SREP decisions. This policy is the main driver of the marginal increase in the average Pillar 2 requirement from 2.1% in 2020 to 2.3% in 2021 (individual requirements are published on the ECB website).

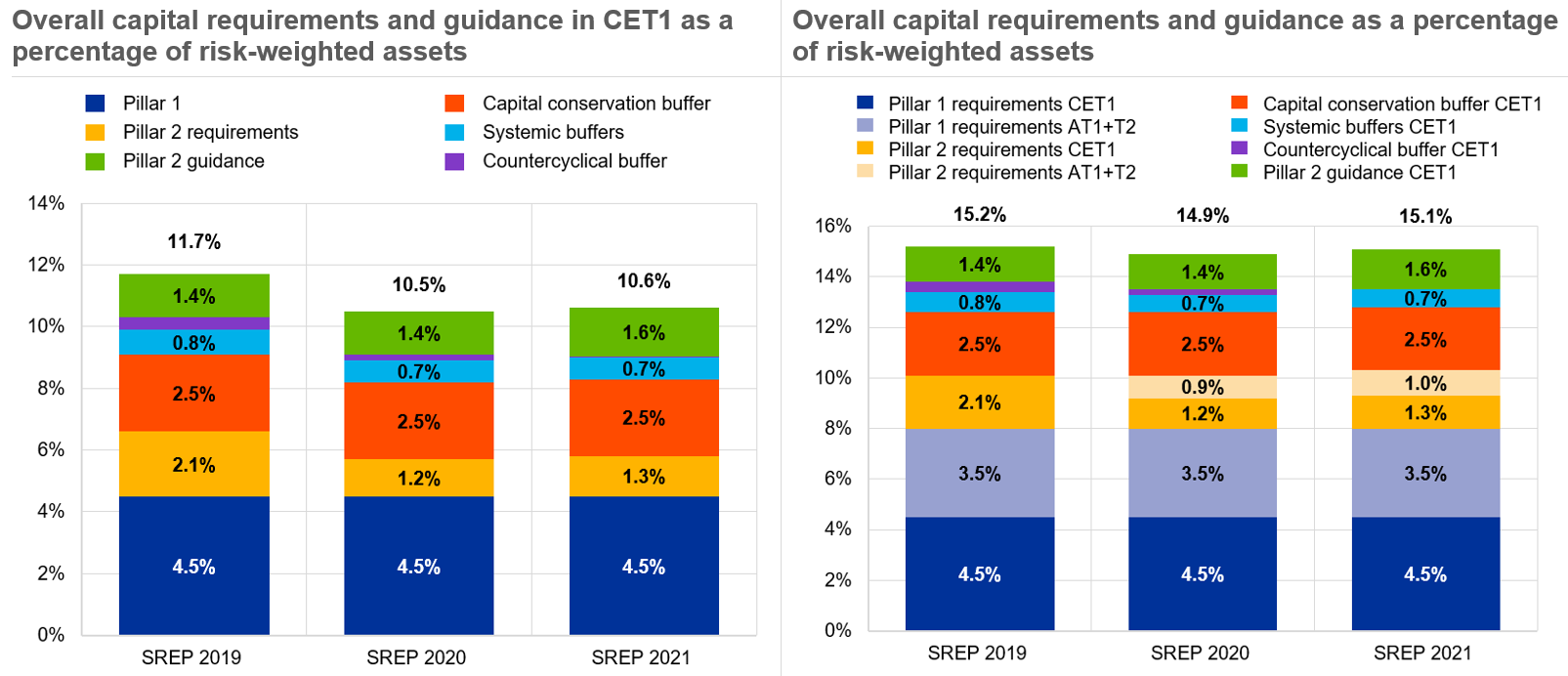

The results of last year’s stress test exercise indicate that the banks we supervise are resilient overall and would be able to cope with further adverse economic developments were they to arise in the future. But the exercise also identified downside risks. Under the adverse scenario, the CET1 capital ratio of the banks in the sample fell by 520 basis points. In this scenario, capital depletion was mostly driven by loan losses and, for larger banks which are more exposed to equity and credit spread shocks, by losses stemming from asset repricing adjustments. Our decisions on Pillar 2 guidance followed a new methodology, strengthening the link between the guidance and the stress test result, and were for the first time published in accordance with a bucketing approach, so as to increase the transparency of supervisory methodologies and outcomes. On average, the downside risks identified by our stress test led to a marginal increase in the Pillar 2 guidance, from 1.4% in 2020 to 1.6% in 2021.

The overall total capital requirement (OCR) and guidance increased by only 20 basis points in 2021, reaching 15.1% on average (up from 14.9% in 2020). This is because the increase stemming from our SREP decisions was partially offset by a decrease in the average countercyclical capital buffer.

Chart 5

SREP requirements and guidance have increased marginally

Sources: SREP 2021 values based on 108 decisions applicable as at Q1 2022; SREP 2020 values based on 112 decisions; SREP 2019 values based on 109 decisions.

Note: Capital requirements and guidance decided during an annual SREP assessment are applicable as of the following year.

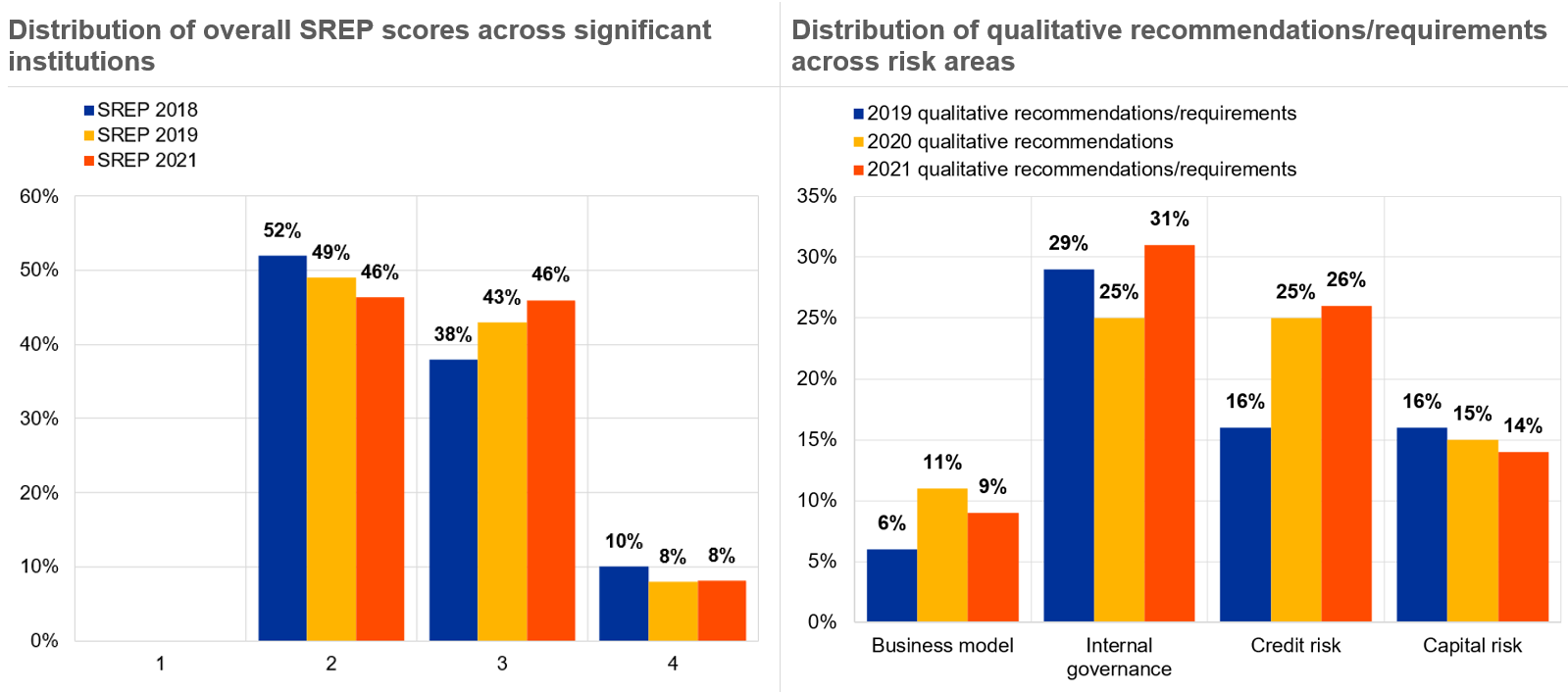

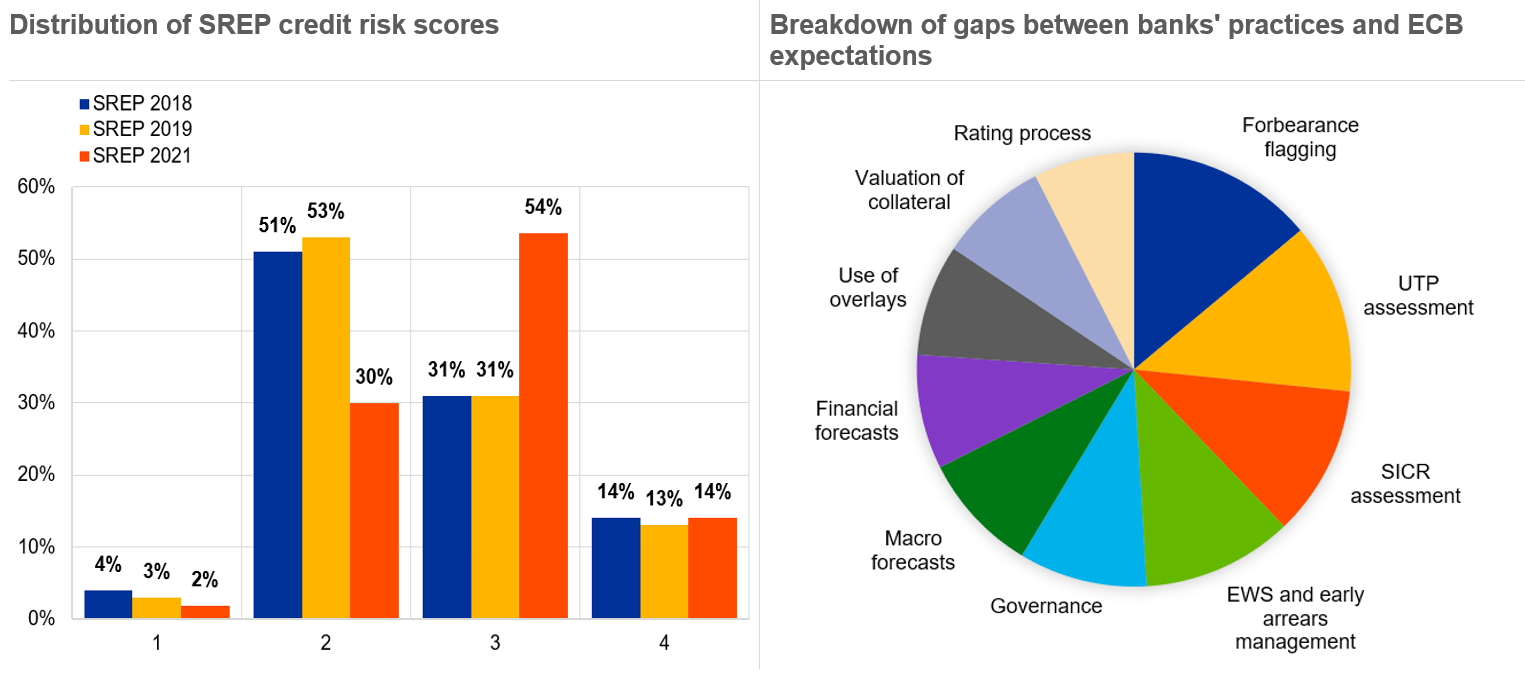

The average overall SREP score of supervised banks remained broadly stable in 2021 compared with 2019. It is fair to say that these results are better than anticipated: supervisors and banks faced tremendous uncertainty when the pandemic broke out, which led supervisors to suspend most components of the SREP methodology in 2020. At the end of the pragmatic SREP 2020, the risk outlook for banks remained shrouded in uncertainty. Cliff effects were a real and valid fear, owing to the expiry of debt moratoria and other support measures. But as the European economy stabilised during 2021, the uncertainty subsided, largely thanks to continued support by the official sector. In the end, there was only a minor increase in the number of banks receiving a score of 3 compared with 2019 and a corresponding decrease in banks awarded a score of 2 (see Chart 6).

Chart 6

SREP 2021 results are broadly stable relative to previous years’ scores; credit risk and internal governance remain the primary focus of supervisory action

Sources: SREP 2021 values based on 108 decisions; SREP 2020 values based on 112 decisions; SREP 2019 values based on 109 decisions; SREP 2018 values based on 107 decisions.

Credit risk controls remain the key focus

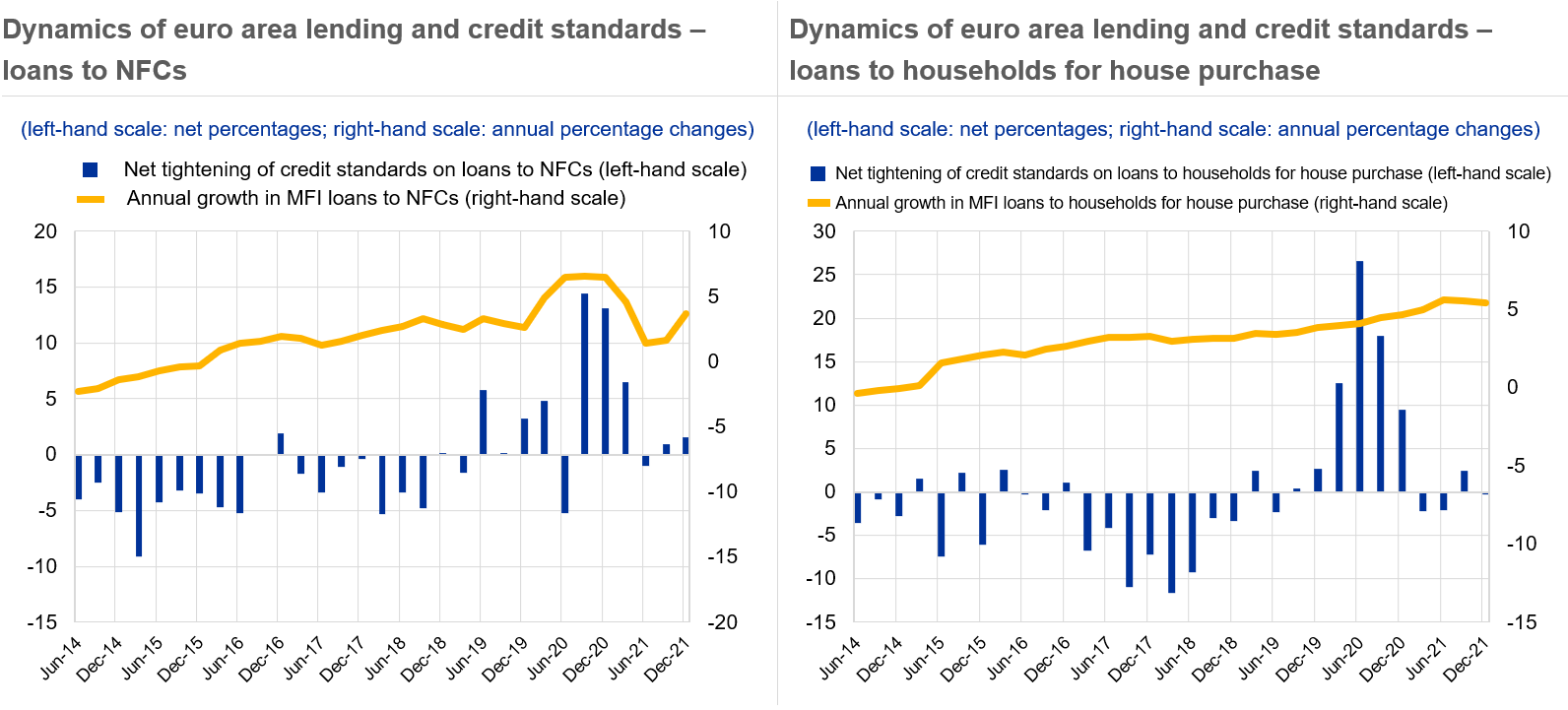

When I presented the results of the previous SREP cycle roughly one year ago, I discussed the key role of public support and supervisory relief measures in curtailing lending procyclicality at the onset of the pandemic. Aggregate lending continued to grow throughout 2021, albeit not uniformly across different borrower types. After a significant acceleration in 2020, which allowed firms to stock precautionary liquidity, corporate lending slowed down markedly in 2021. By contrast, lending to households continued to grow, driven by record high increases in residential mortgage lending. These dynamics spurred house price inflation, which prompted the ECB to flag the build-up of vulnerabilities in several countries in its Financial Stability Review. In this context, we will maintain our strong focus on credit risk controls.

Chart 7

Growth in lending to NFCs has moderated after firms borrowed heavily at the start of the pandemic, while mortgage lending has driven growth in lending to households

Sources: Euro area bank lending survey and BSI data.

Notes: The MFI sector excludes the Eurosystem. Loans are adjusted for loan sales and securitisation; in the case of NFCs, loans are also adjusted for notional cash pooling. Net percentages are defined as the difference between the sum of the percentages of banks responding “tightened considerably” and “tightened somewhat” in the bank lending survey and the sum of the percentages of banks responding “eased somewhat” and “eased considerably”. The latest observations are for December 2021.

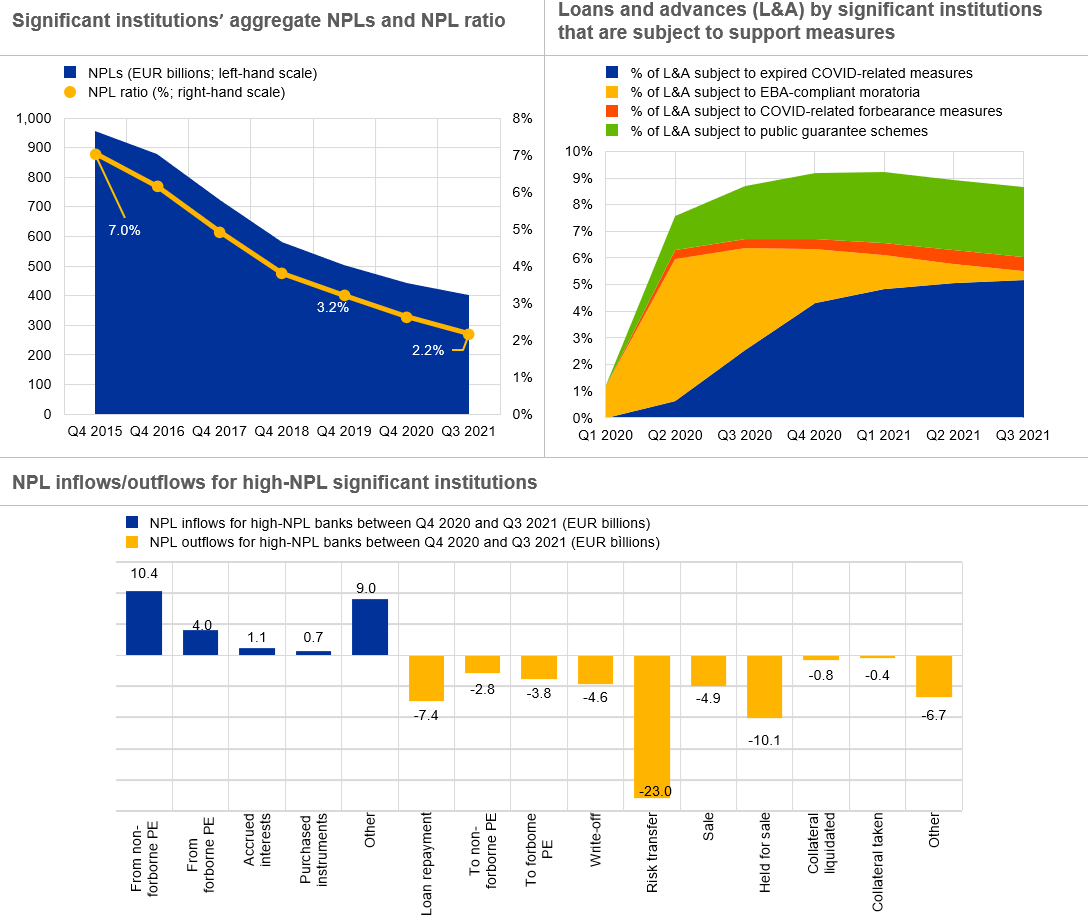

Credit has continued to flow to the real economy and, as yet, there has been no clear evidence of a deterioration in asset quality. The non-performing loan (NPL) ratio of significant banks continued to fall throughout the pandemic. Market stability and investors’ search for yield enabled high-NPL banks to make substantial progress with their NPL resolution strategies. Most importantly, far-reaching government support measures for households and corporates have temporarily preserved borrowers’ capacity to repay loans.

Chart 8

Stocks of non-performing loans (NPLs) have declined further, thanks in particular to the execution of high-NPL banks’ strategies and exceptional public support measures

Sources: Supervisory reporting and ECB calculations.

Notes top charts: The sample for Q3 2021 comprises 113 SIs. The number of SIs can change from one reference period to another owing to amendments to the list of SIs following assessments by ECB Banking Supervision.

Note top-right chart: Data on forbearances related to COVID-19 measures are unavailable for Q1 2020.

Note bottom chart: This chart shows flows for high-NPL banks between Q4 2020 and Q3 2021. The sample for Q3 2021 comprises 23 SIs.

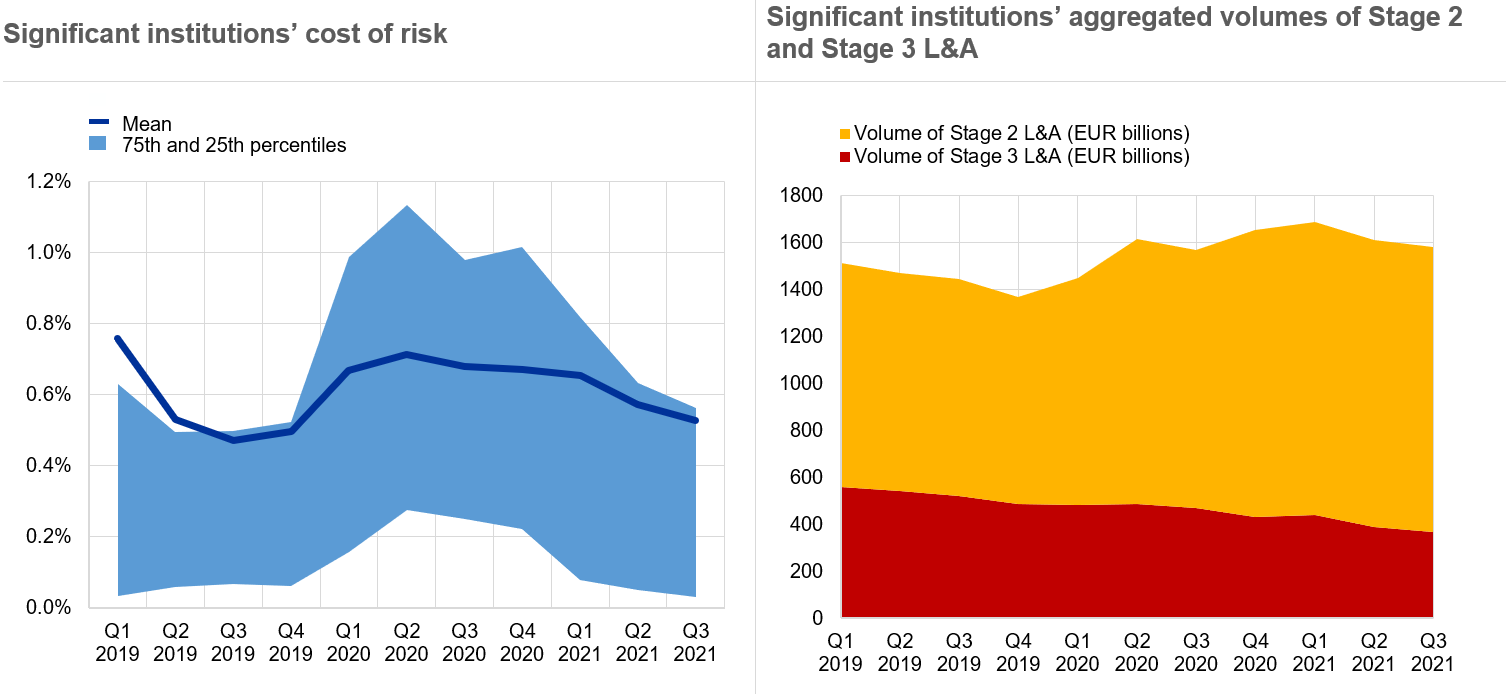

The positive developments of 2021 and the continued improvement of macroeconomic forecasts prompted banks to reduce the cost of risk – a measure of their provisioning– from the peak levels seen in 2020, while still keeping it slightly above the levels seen before the pandemic. As part of the SREP, we assessed banks against the supervisory expectations on credit risk controls set out in our 2020 letters to CEOs, imposing mostly qualitative measures where banks’ remedial actions were considered unsatisfactory. Assessing the level of risk remains challenging, and the outlook still points to signs of latent credit risk, so it is crucial that banks strengthen their credit risk controls as much as possible.

Chart 9

While banks’ cost of risk is falling back towards pre-pandemic levels, signs of deterioration in credit quality continue to be observed …

Sources left-hand chart: Supervisory reporting and ECB calculations.

Notes left-hand chart: The mean represents a weighted average across SIs. The sample for Q3 2021 comprises 108 SIs. The number of SIs in the sample can change from one reference period to another owing to amendments to (i) the list of SIs following assessments by ECB Banking Supervision and (ii) banks’ reporting requirements.

Source right-hand chart: Supervisory reporting.

Notes right-hand chart: The sample for Q3 2021 comprises 103 SIs. The number of SIs in the sample can change from one reference period to another owing to amendments to (i) the list of SIs following assessments by ECB Banking Supervision and (ii) banks’ reporting requirements.

The share of underperforming loans (known as stage 2 loans) did not recede in 2021. In some of the sectors considered more vulnerable to the pandemic, underperforming loans continued to increase substantially during 2021. This is especially noticeable in accommodation and food services, and the air transport and travel-related sectors. Loans which benefit or have benefited from COVID-19 support measures also appear to have a riskier profile than the aggregate loan book. In sum, while credit quality looks benign on the whole, certain segments of the balance sheet may still deteriorate. These deserve close attention.

Chart 10

… raising asset quality concerns in relation to specific sectors and loans that have benefited from support measures

Source top chart: AnaCredit.

Notes top chart: This chart shows the economic sectors (NACE Rev. 2 classification) with the largest absolute increases in Stage 2 exposures between Q3 2020 and Q3 2021. The sample comprises credit institutions reporting the selected data points to AnaCredit as at September 2021.

Source bottom chart: Supervisory reporting.

Notes bottom chart: The sample comprises 113 SIs. The number of SIs in the sample for a given reference period reflects changes resulting from amendments to the list of SIs following assessments by ECB Banking Supervision.

Our review of banks’ credit risk controls focused on areas such as the reporting of forbearance measures, the reclassification of loans into different stages of IFRS 9 and unlikely-to-pay assessments. We identified credit risk deficiencies in 70% of banks under our supervision and followed up accordingly, issuing 14% more qualitative credit risk measures than in the previous year. The severity of the findings increased as well, a further indication of our heightened supervisory scrutiny of credit risk management practices. But while the dynamics of the pandemic highlighted deficiencies in credit risk practices, the issues were typically structural. Almost two-thirds of the banks under our supervision saw no change in their credit risk score, while almost one-third saw a deterioration.

Chart 11

In SREP 2021 we followed up on legacy issues and made renewed efforts to improve credit risk controls

Sources: SREP 2021 values based on 108 decisions; SREP 2019 values based on 109 decisions; SREP 2018 values based on 107 decisions.

Note right-hand chart: A letter to banks’ CEOs spelled out the ECB’s expectations. Their feedback and remedial actions were reviewed centrally, and supervisors communicated the results of that assessment to banks.

Banks must tackle structural business model and governance shortcomings

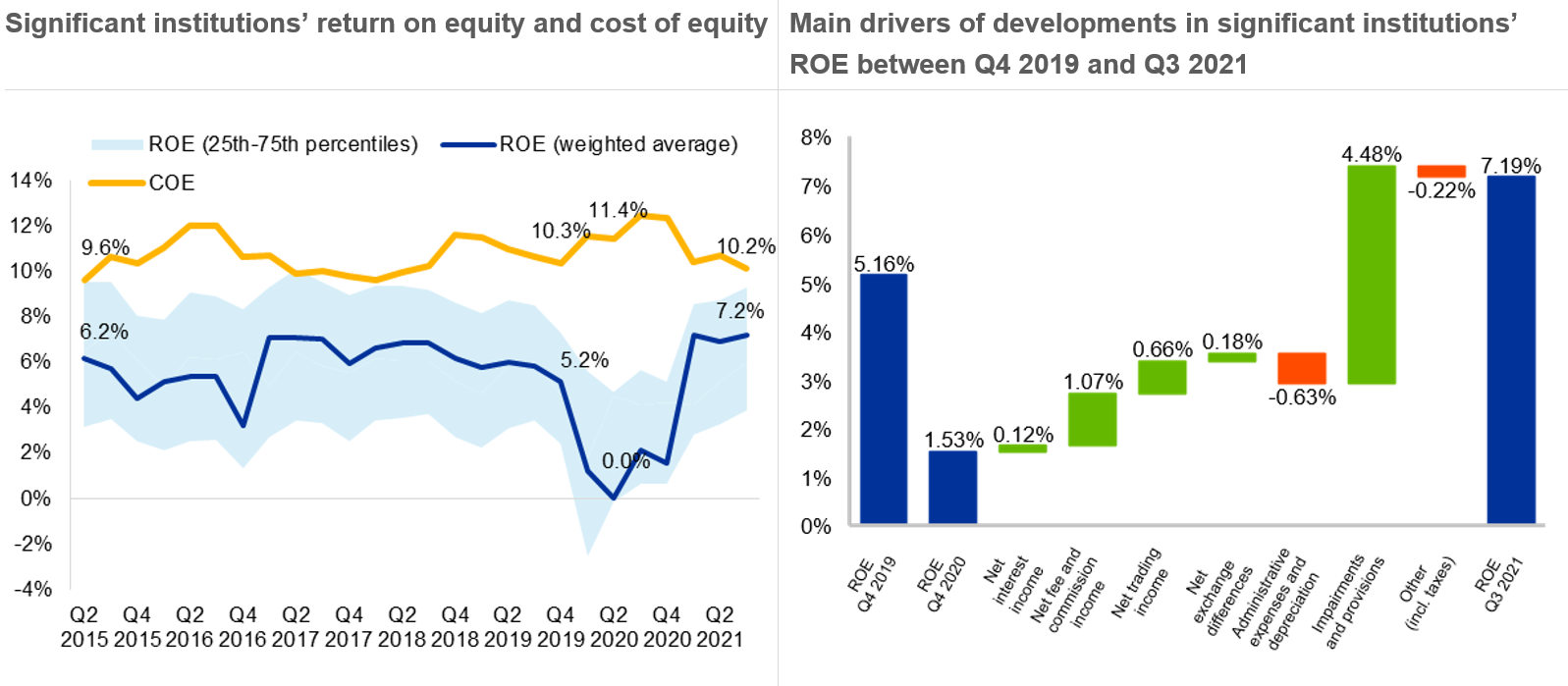

Structural issues are at the core of another challenge for European banks: profitability.

Since the financial and sovereign debt crises, most European banks have not been able to earn their cost of equity. While return on equity rebounded quite strongly in 2021, this improvement was largely cyclical and driven by the release of provisions.

Trading business and fee and commission-generating activities also played a supporting role, confirming that income diversification can be a source of resilience in the face of shocks. Analysis carried out by the ECB[1] shows that, during the pandemic, euro area banks increased their global market share of investment banking activities related to debt capital markets and syndicated lending. If this proves to be a sustainable development and is not simply the result of buoyant debt issuance during the pandemic, it may help European banks improve their profitability. From a supervisory perspective, we will be working to ensure that income growth, and non-interest income in particular, is not pursued outside properly defined risk appetite and risk management frameworks, in the context of aggressive search-for-yield strategies such as those observed even during the pandemic.

Chart 12

Significant institutions’ profitability recovered in 2021, but remains structurally low overall

Sources left-hand chart: Supervisory reporting and ECB calculations.

Notes left-hand chart: For return on equity (ROE), the sample comprises 113 SIs as at Q3 2021. The number of SIs can change from one reference period to another owing to amendments to the list of SIs following assessments by ECB Banking Supervision. Cost of equity (COE) is computed based on data for the 113 banks classified as SIs in Q3 2021 (constant sample) and following the methodology in the ECB publication “Measuring the cost of equity of euro area banks”. The chart plots the weighted average using the book value of equity.

Source right-hand chart: Supervisory reporting.

Notes: The sample comprises 113 SIs for Q3 2021, 112 SIs for Q4 2020 and 113 SIs for Q4 2019. The chart displays linearly annualised profitability figures. The number of SIs can change from one reference period to another owing to amendments to the list of SIs following assessments by ECB Banking Supervision.

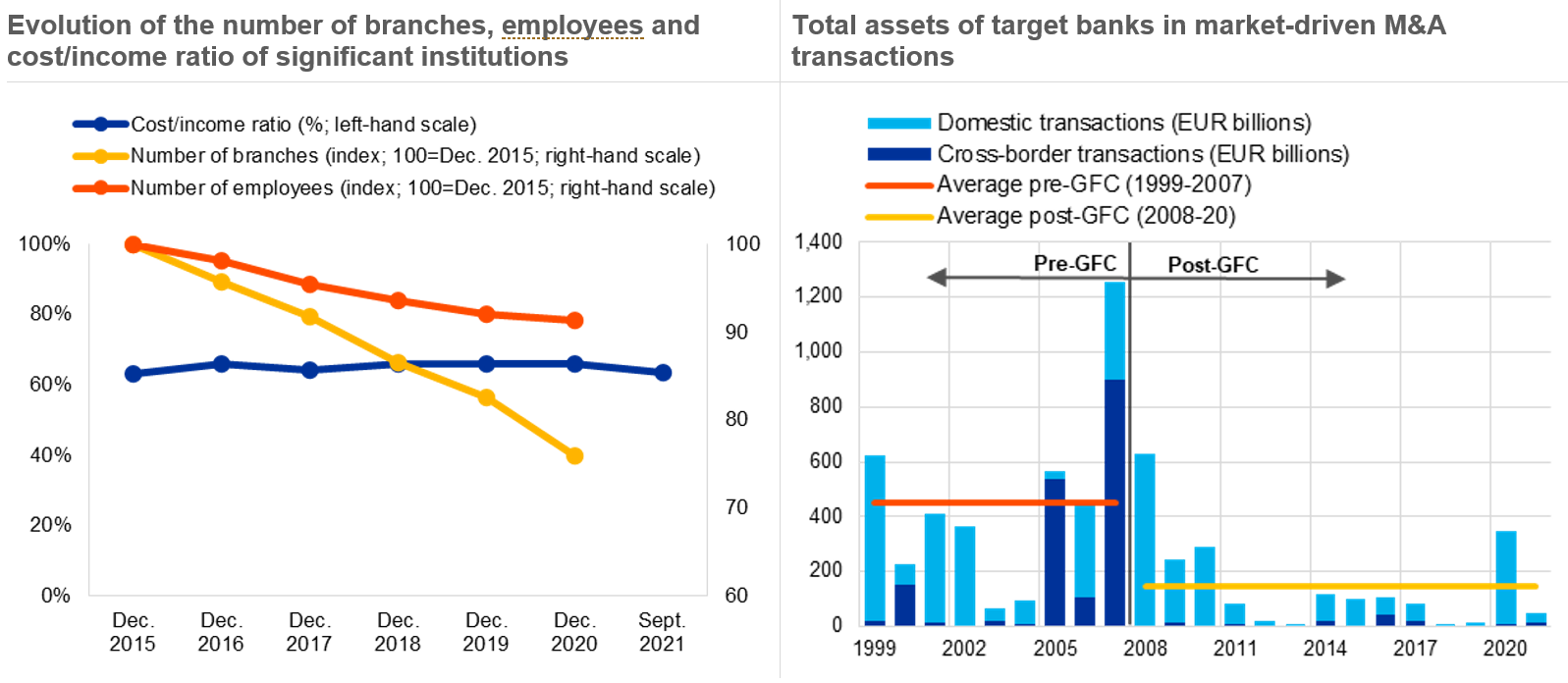

The only realistic way for banks to address the profitability challenge is for them to take decisive action to improve their cost efficiency and refocus their business models towards longer-term value creation opportunities. It is precisely in relation to sustainability – in other words, the capacity to steadily generate medium to long-term profitability – that we issued the majority (63%) of our qualitative recommendations in the 2021 SREP assessment of business models. In recent years we have seen banks make successful cost reduction and structural transformation efforts, with more consolidation at the level of business lines and a revival in mergers and acquisitions in 2020. But large parts of the banking sector are still plagued by long delays in implementing these changes, an inability to adapt business models to the challenges raised by the pandemic, and limited capacity to act on previous supervisory measures targeting business models.

The aggregate cost-to-income ratio, which has fluctuated between 63% and 66% for several years now, decreased only marginally in 2021, to below pre-pandemic levels. While some of the cost reductions observed in 2020 proved to be only temporary, evidence suggests that profitability and cost efficiency metrics respond to transformative changes with a slight delay, owing to the material upfront costs of structural measures and the delayed realisation of the synergies. Behind this aggregate result, the most important improvements in cost efficiency for 2021 were reported by custodians and asset managers, corporate and wholesale lenders and global systemically important banks. Overall, only a handful of banks under our supervision saw an improvement in their business model SREP score in 2021, while for the majority this score was unchanged.

Chart 13

While structural business model vulnerabilities persist, ongoing efforts to address banks’ efficiency may pay out in the longer term

Sources left-hand chart: Supervisory reporting and ECB Banking Structural Statistical Indicators (SSI).

Notes left-hand chart: Cost/income time series considers a changing sample of institutions which comprises 113 SIs as at Q3 2021. ECB SSI database includes euro area (changing composition) institutions, and latest available data are for 2020.

Sources right-hand chart: Dealogic, Orbis Bank Focus, Refinitiv, and ECB calculations.

Notes right-hand chart: Relevant M&A transactions exclude the acquisition of assets, repurchases, privatisations, leveraged buyouts, joint ventures and restructurings. They meet the following criteria: (1) the acquired stake is above 10%, corresponding to a qualifying holding; (2) the initial stake is below or equal to 50%; and (3) the final stake is above 50%. In cases where multiple banks are involved in a deal as target and/or acquirer, at least one of the targets and/or acquirers have to be domiciled within the euro area. GFC stands for global financial crisis.

No bank can afford to overlook the potential for efficiency improvements offered by digital technologies. The pandemic has significantly accelerated the shift to services being provided digitally, and banking has been at the forefront of this development. Most people are now acquainted with online or mobile banking. This changed environment creates opportunities for banks to boost their revenues – they can increase their customer base without the need for a physical presence. New digital products and services can be offered at very low marginal cost, and pricing can be improved through advanced techniques for processing massive amounts of data. Digital technologies offer banks the potential to increase their cost efficiency by trimming branches and reducing personnel expenses, and by enabling them to provide more integrated platforms, data repositories and distribution tools across their groups.

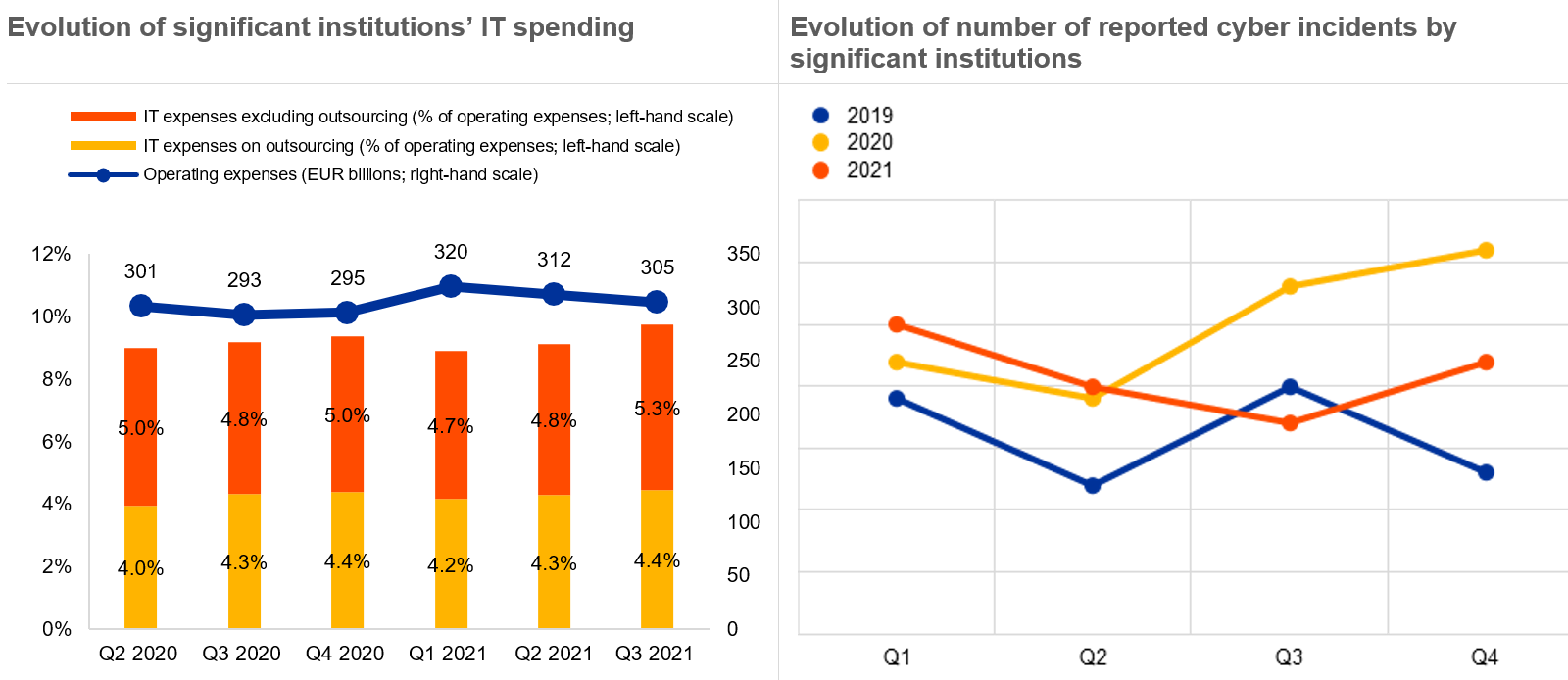

While digital technologies can provide new answers to fundamental and pressing questions, they pose new challenges, too. And not only to banks; they also pose challenges for regulators and supervisors. IT and cyber risk is increasingly becoming a key area of focus for ECB Banking Supervision.

Banks are expected to act to mitigate IT and cyber risks. Where security vulnerabilities have been detected, banks have been asked to draft and implement remediation plans. They have also been asked to establish and document their IT strategy, to adequately staff critical IT functions and to enhance staff training. The recent increase in IT spending that has accompanied the increased reliance on digital strategies has often taken the form of increased reliance on outsourcing, which may raise issues around the continued availability of critical functions if third-party providers suspend their services. And despite the supervisory pressure exercised in recent years, weaknesses in banks’ IT infrastructure and risk data architecture are still a major obstacle to effective data aggregation at the group level. For example, we often see different IT systems being used to perform the same or similar tasks across banking groups.

Chart 14

Sound digital transformation strategies seen as a catalyst to foster efficiency, but related IT/cyber risk challenges need to be tackled

Sources left-hand chart: Supervisory reporting and ECB calculations.

Notes left-hand chart: The sample consists of 110 SIs. The number of institutions is consistent over the reference periods represented. Chart displays linearly annualised operating and IT expenses figures. The cut-off date for data was 24 January 2022.

Sources right-hand chart: ECB cyber incident reporting and ECB calculations.

Notes right-hand chart: The reporting sample consists of all significant institutions. The number of SIs can change from one reference period to another owing to amendments to the list of SIs following assessments by ECB Banking Supervision.

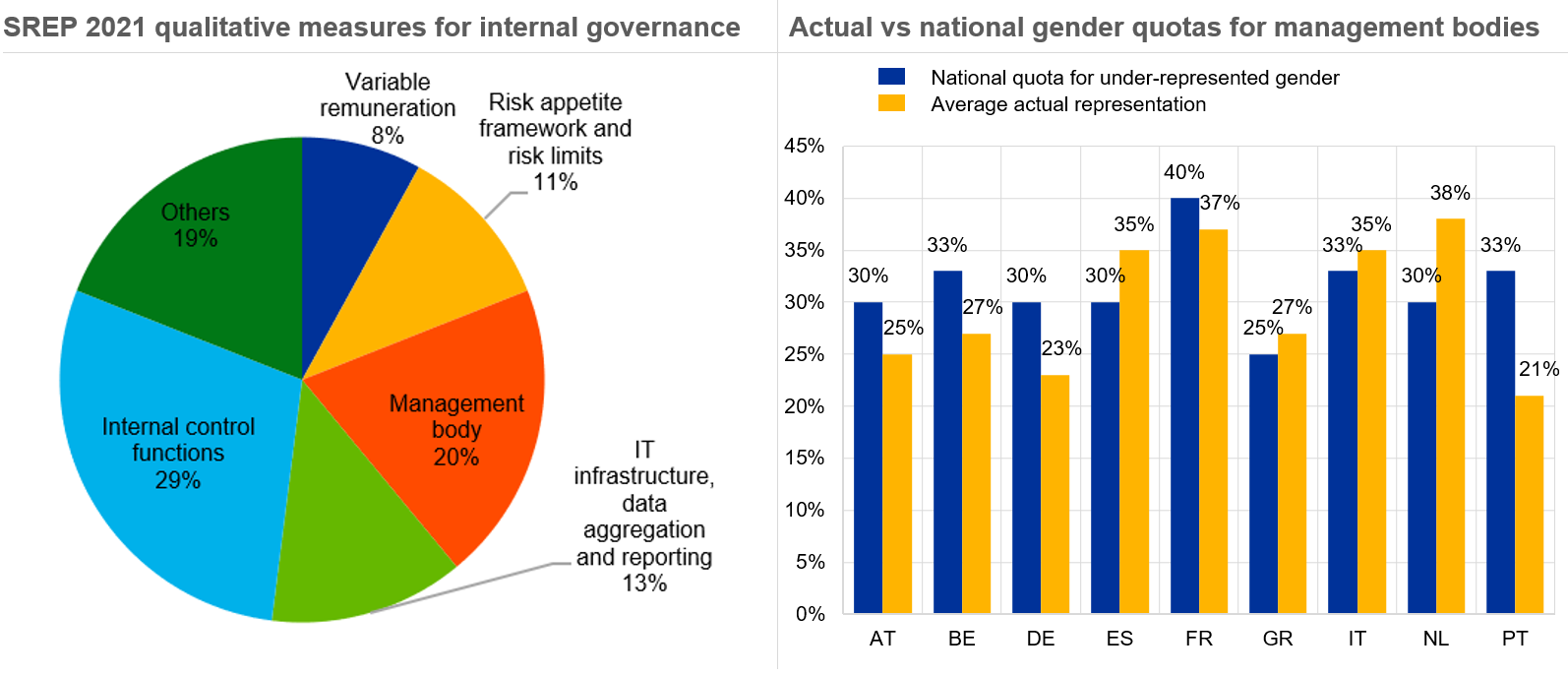

In the 2021 SREP, internal governance remained the area that attracted the highest proportion of our supervisory recommendations. The bulk of these were in response to weaknesses in the functioning of management bodies. First, banks’ supervisory functions often prove ineffective in challenging their management. Second, there is often inadequate staffing of the second line of defence in terms of quantity, quality and status – in a number of cases senior management do not devote sufficient attention to the work of the risk management and compliance functions and do not sufficiently follow up on their findings. And third, insufficient attention is paid to actual and potential conflicts of interests of members of the management body.

These shortcomings in internal governance may blur lines of responsibility, hinder effective risk management and weaken internal checks and balances at all levels. They often go hand-in-hand with insufficient policies to promote diversity across the organisation, starting with the management body. All of this damages banks’ resilience. Diversity in leadership has long been recognised as crucial for effective governance.[2] Targeted policies should span several dimensions, such as age, gender, geographical provenance, and educational and professional background. Succession policies should aim to increase the representation of women in the management body, remuneration policies should be gender-neutral and information should be available on the gender pay gap.

There are national gender quotas for management bodies in nine of the countries participating in the banking union, and there are several cases of significant banks falling short of the quota. Shortcomings in gender balance have been a focus of ECB Banking Supervision for several SREP cycles now. So far, the speed of progress has been disappointing.

Chart 15

Structural deficiencies of management bodies call for a focus on collective suitability and diversity as key drivers of effectiveness

Source left-hand chart: SREP 2021 measures for internal governance (Element 2) based on 108 SREP decisions.

Source right-hand chart: ECB stocktake conducted in 2021.

Notes right-hand chart: The sample comprises 93 SIs. National gender quotas for management bodies apply in nine of the euro area countries (displayed in the chart); in the other euro area countries banks are left to determine their own targets. The scope and application of the quotas may differ according to national legislation.

Risks emerging from market exuberance and climate change

The current business environment for banks is characterised by the increasing pressure of digitalisation and greater competition between banks. And the euro area banking sector is facing at least two additional risks as the end of the pandemic draws nearer.

The first is the risk that the exit from the low interest rate environment may be bumpy, and characterised by sudden corrections in asset prices and spreads, costly deleveraging and unexpected channels of direct and indirect contagion. The second risk is that of a sudden and significant increase in climate and environmental risk.

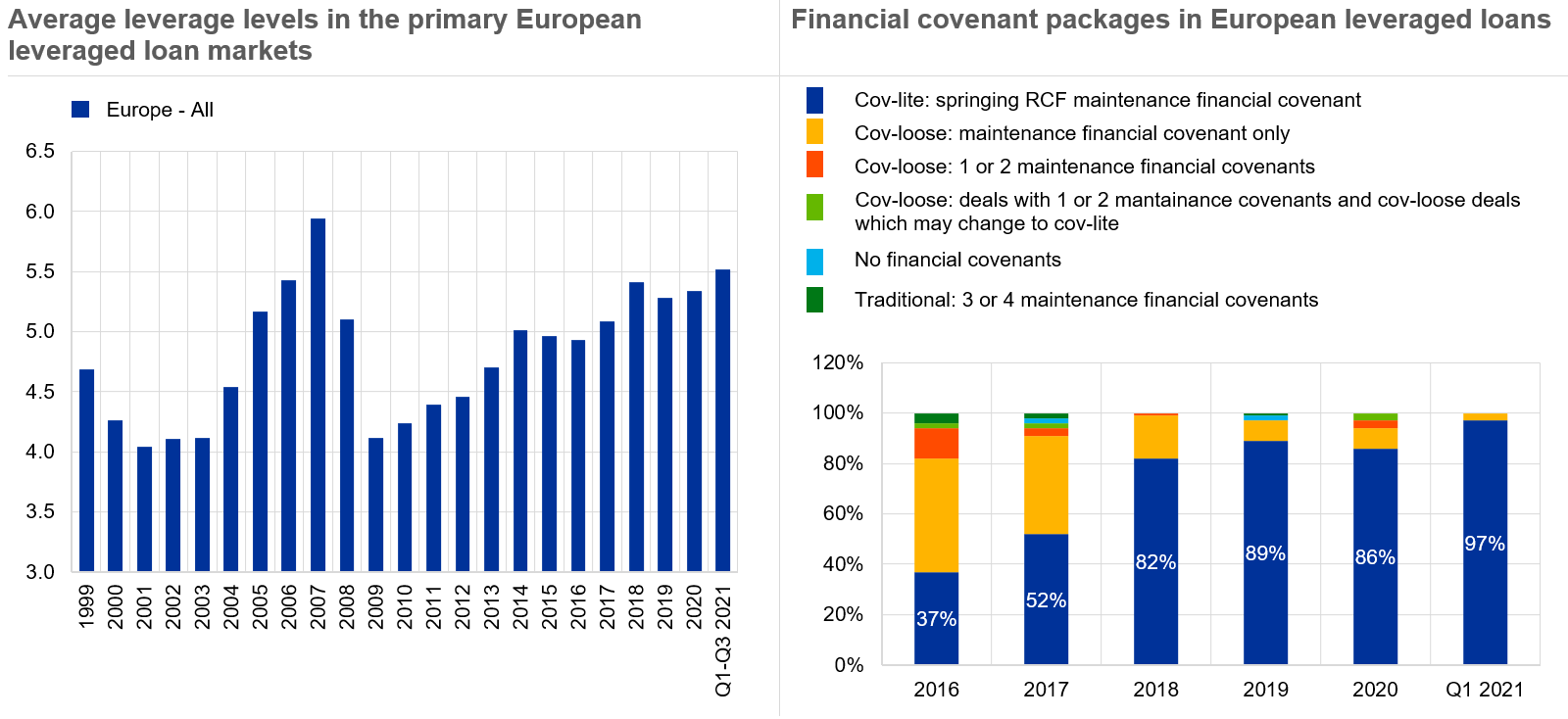

Taking these two risks in turn, the risk of unexpected, material increases in interest rates or credit spreads is a cause for concern in the light of the search for yield strategies some banks have been pursuing in recent years, including throughout the pandemic. The leveraged finance business is a case in point. Lending to structurally riskier counterparties has progressively increased as leverage limits were lifted and investor protection covenants progressively lowered or disregarded. This runs totally counter to our publicly disclosed supervisory expectations. Following a number of dedicated recommendations in the 2021 SREP cycle, we are preparing a letter to banks that are particularly active in the leveraged lending market to clarify our expectations. And we may well consider quantitative requirements in the 2022 cycle if banks fail to respond to our expectations.

Chart 16

Vulnerabilities are growing in the leveraged finance segment on the back of search for yield, higher leverage and weaker covenants …

Sources left-hand chart: S&P Leveraged Commentary & Data (LCD), Q3 2021.

Notes left-hand chart: Leverage is computed as total debt/EBITDA using pro-forma and unadjusted EBITDA levels. EBITDA stands for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation.

Source right-hand chart: Reorg Research, Q1 2021.

Note right-hand chart: Figures based on Reorg calculations.

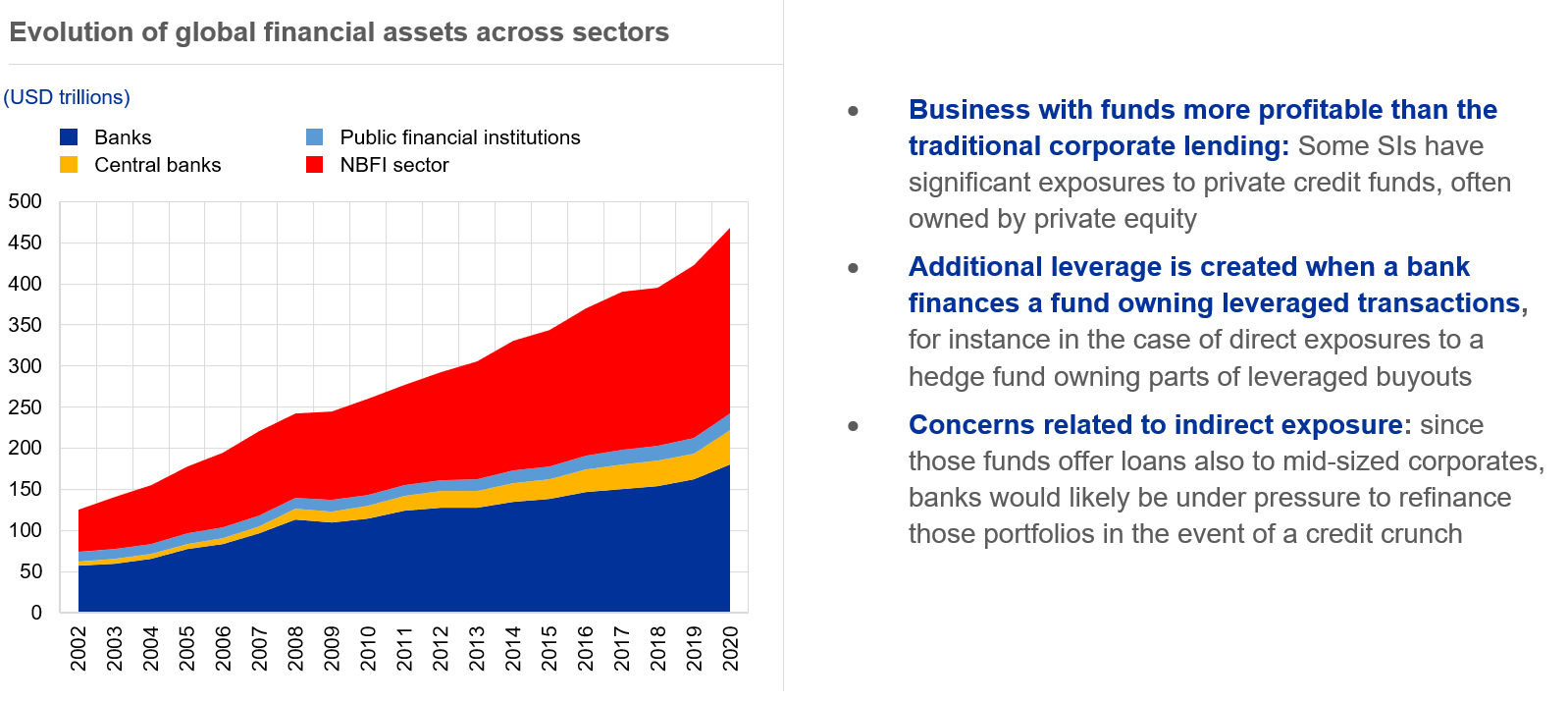

As the overall indebtedness of the private sector increased during the pandemic, the banking sector also increased its indirect exposure to leverage through non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs), such as private equity-owned credit funds or family offices, as a means of exploring more profitable alternatives to traditional banking.

Diverse risk management practices for counterparty credit risk, weak client management principles and insufficient transparency clearly emerged as sources of global concern in this area. Vulnerabilities stemming from the interplay between credit, market and counterparty risks showed their negative potential in the Archegos case and will attract enhanced supervisory attention.

Chart 17

… but also towards NBFIs where higher risk-taking and lagging transparency observed in some segments have triggered large losses for some banks

Source: Financial Stability Board, Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation 2021.

Note: Financial assets held in the euro area and 21 other countries (AR, AU, …) from 2002 to 2020.

Turning to the second risk I mentioned, climate change also demands decisive and immediate action from banks. Physical and transition risks are already materialising and having a direct impact on banks. Extreme weather events can harm borrowers’ ability to repay their debts and depreciate the value of the assets used as collateral against bank loans. Legislation and policies aimed at driving the transition to a low carbon economy, such as carbon-pricing or the banning of carbon-intensive activities, together with shifting consumer preferences towards goods and services that are more sustainable, will have a significant impact on climate-sensitive economic sectors and the broader economy, particularly in the case of an abrupt transition.

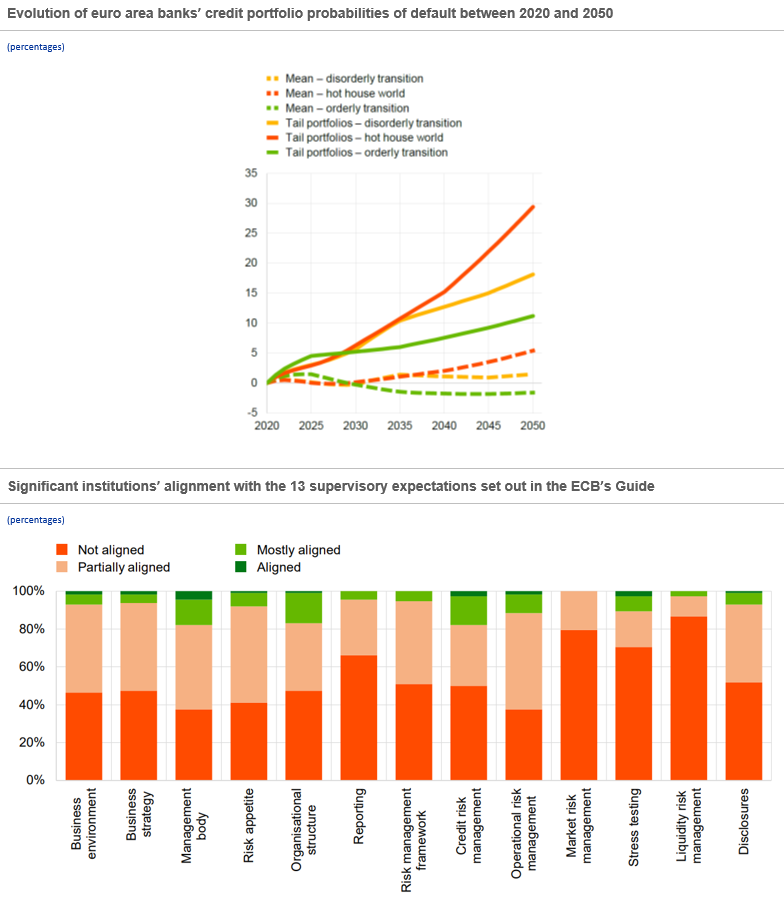

Last year we finalised our benchmarking of banks’ self-assessments in relation to the supervisory expectations set out in the ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risks. All banks acknowledged that they are all still a long way from meeting the supervisory expectations we have laid out for them. We have flagged the gaps between practices and expectations in our SREP letters, which include a number of qualitative recommendations.

This supervisory action will be intensified in the 2022 SREP cycle: we will conduct a thematic assessment of the progress banks have made in strengthening their ability to identify, measure and manage climate and environmental risks. We will also run our first climate stress test exercise. The outcomes of the 2022 supervisory assessments will only be reflected in qualitative measures and recommendations. Any possible quantitative impact will be indirect, via the SREP scores on Pillar 2 requirements. But I must stress that this is not the ultimate goal. We will gradually start treating climate-related risks just like any other risk, meaning they will be reflected in all relevant supervisory requirements.

Chart 18

Banks’ management of climate-related and environmental risk lagging behind despite major challenges ahead

Sources left-hand chart: ECB calculations based on NGFS scenarios (2020), AnaCredit, Orbis, Urgentem and Four Twenty-Seven data (2018).

Notes left-hand chart: The sample of bank exposures covers around 80% of total AnaCredit exposures held by approximately 1,600 euro area banks which reported non-zero exposures in the AnaCredit database in December 2018. For a full description, see ECB, “ECB economy-wide climate stress test”, Occasional Paper Series, No 281, September 2021.

Sources right-hand chart: ECB Banking Supervision, “The state of climate and environmental risk management in the banking sector”, November 2021.

Notes right-hand chart: The assessment covered significant institutions at the highest level of consolidation as at 1 January 2021. For a full description of the 13 supervisory expectations, see ECB Banking Supervision, “Guide on climate-related and environmental risks”, May 2020.

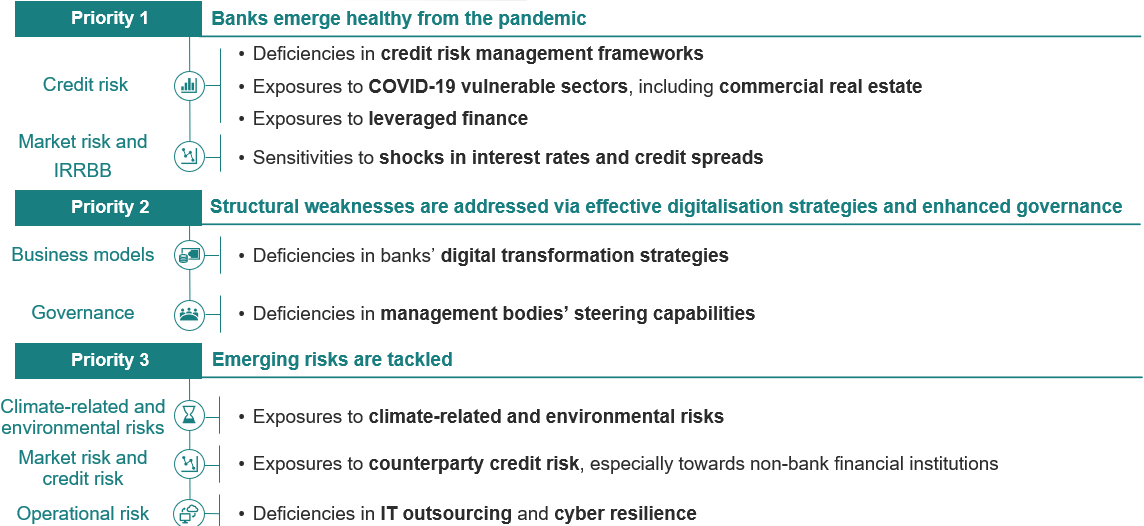

Looking ahead: supervisory priorities for 2022-24

The 2021 SREP cycle mainly focused on the challenges raised by the pandemic, and in particular on credit risk controls and the follow-up to the expectations we set out in our letters to CEOs in 2020. But it also identified and started tackling the emerging risks linked to the exit from the extraordinary support measures deployed during the pandemic, to digitalisation in financial services and to climate change.

In December we published our supervisory priorities for the next three years. The most immediate challenge is to ensure that banks emerge from the pandemic healthy. They also have an unprecedented opportunity to decisively tackle the structural weaknesses that have adversely affected their profitability and market valuations in recent years. Concrete steps towards completing the banking union in the coming months would create momentum for the necessary structural adjustments. But banks have to do their part by reviewing their business models and market positioning within the banking union. Our supervisory processes will accompany this transition. Finally, our priorities will gradually move towards the emerging risks triggered by the digital transformation of banking, the climate transition and the excessive leverage in our economy, risks that are also being fuelled by new, less regulated players outside the banking sector.

Chart 19

2022-24 supervisory priorities tackle the impact of the pandemic, banks’ long-lasting vulnerabilities and emerging risks

Source: ECB Banking Supervision - Supervisory priorities for 2022-2024.

Thank you very much for your attention. I now look forward to your questions.

* * *

My first question is on those six banks that came up short of your total requirements. So can you tell us more about that? Last year you said that banks that failed to meet were chiefly to do with structural issues rather than the pandemic; is it still the case? Or are we looking here at cases where the impact of the pandemic resulted in banks falling short?

My second question is about cyberattacks, because some of your colleagues on the other side of the ocean have warned US banks about possible retaliatory attacks from Russia in the context of the Ukraine crisis. How is the ECB tackling that risk?

First of all, let me say that six banks – that, as I mentioned, should go back to four at the end of the year – is an improvement compared to the previous year, when we had around ten banks in that region. As I mentioned, this is mainly due to structural reasons, so these are banks that have, let’s say, long-standing difficulties and are gradually trying to rebuild their franchise, rather than a specific pandemic-driven impact.

Cyber risk is indeed an area of increased attention for us. We had an extensive discussion in our Supervisory Board recently and decided to raise the level of priority that we are attributing to this issue going forward. So it will be an area of attention generally for our banks. We are indeed also asking them to strengthen their cyber hygiene measures and look at a potential increase in attacks and in the danger of these attacks going forward. I would say that this is something which we will focus on more during this year, and something which we also flag to the attention of banks in relation to the potential worsening of the global tensions that could indeed trigger more attacks.

When do you see the peak for non-performing loans (NPLs), and what amount of NPLs are you expecting at this peak? You were pessimistic at the beginning of the pandemic, but what are your expectations now?

Secondly, you have removed capital and leverage relief for banks, but what about public measures? Would you be in favour of an extension of moratoria in public guarantees?

Well, luckily enough the peak in NPLs is behind us so I hope that… If you look at the trajectory of NPLs in recent years, let’s say it has been continuously going downwards. If I remember well, the NPL ratio, the latest figure we have from Q3 of the NPL ratio is 2.2%, which is the absolute minimum since the start of the banking union. I must say, I also have to pay tribute to those banks which had significant legacy portfolios of NPLs for having been able to continue addressing this issue via securitisation, sales or write-downs of these NPLs, even during the pandemic. So, improving their position also during the pandemic.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that we should lower our guard. Our point to banks and our focus on credit risk controls is exactly that: in order to avoid a still-possible fallout of the pandemic when the public support measures are totally withdrawn – also the ones that are supporting banks’ borrowers, so households, and small and medium enterprises and corporates – we will need to make sure that banks are tackling these issues in a timely fashion, that they correctly classify the loans, that they correctly perform the “unlikely to pay” assessments. This has been the focus, actually the core focus, of the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) exercise this year.

On the removal of our measures – we removed our relief measures because we think that now the banks are in a fairly strong position and there doesn’t seem to be any need for those measures. And we see that all other relevant measures are being withdrawn as well. You mentioned moratoria; moratoria have been removed in most Member States. Our assessment, if I remember well, is that only 0.3% of the loans of significant institutions under our supervision are now benefiting from moratoria. So there is only a very marginal portion of lending under moratoria. But anyway, it’s not very important because we asked banks in any case to look through moratoria and assess the quality of their counterparts irrespective of the support measures.

Thanks very much to the press department for sending out the press release before the press conference. For us newswire journalists it makes a huge difference, so thank you. We enjoy the press conference more. I have a few questions on leveraged loans and the actions you’re taking there. First of all, I love the ECB’s very polite language. Maybe you could tell us what “dedicated recommendations” are. I take it it’s a bit more forceful than the term implies.

Then if you could also tell us what quantitative requirements could be, what’s in your toolbox here? Is it just the hard stick of saying: your Pillar 2 Requirements (P2R) will go up next year if you do not comply? Is it maybe something more in terms of a limit, a cap on the volume of highly leveraged transactions, for example? I guess along the lines of what you do with large exposure limits in other parts of supervision.

Then maybe you could also spell out to us a little bit: you’ve been talking about leveraged loans for so long, it feels, now, and I understand that you need to have a grounded base on which you can issue recommendations or you can tell banks to do something. But how come it’s taken so long? And surely if there is so much risk out there right now, then why is it okay to wait until next year to have the actual quantitative impact from that?

You’re right, this is not a new topic. We have been raising this issue for a while now. We actually set out our guidance in 2017 and we told banks “we expect that you only exceptionally grant exposures which have an excessively high leverage”. We quantify this “excessively high” as a loan-to-EBITDA ratio greater than six. This was also something that we discussed and agreed with our colleagues at the global level. Now, there hasn’t been sufficient follow-up to this guidance. The way in which our teams operate in these cases is that they engage with the banks, because of course we need to tailor our general guidance to the specific risk profile, the risk controls of each individual bank. Our attention has been focused very much on what we call the risk appetite framework. So we asked banks to have a mechanism internally in their risk management, setting clear limits and helping to lower the risks in this part of their portfolios.

This has been a long dialogue with the banks. We have achieved some successes, but also in some cases we notice some reluctance of banks to follow up on our qualitative recommendations in these areas. We have seen that the amount of highly leveraged transactions increased. The share of covenant-lite transactions increased as well, so the protection for banks decreased. So we still perceive that there is a significant risk in this area. This is not across the board; some banks have improved and strengthened their internal mechanisms. So we are now at the moment in which we will clarify in a letter, as I mentioned, our expectations for all banks. Then we will do dedicated work for each bank and if, eventually, we are not satisfied with the progress, it would be mainly the capital stick that will be used, so the Pillar 2 charges. That’s the basic idea.

Three small questions. One: the Russian exposure of European banks, how big is it in size?

Then: have you specifically warned against Russian cyberattacks, or was it a general warning?

Third question: with business models, what would happen if a bank would spin off or want to spin off a business line which is profitable and which leaves this bank as a monoliner? Is this in a wishful scenario for a banking supervisor?

On your first question, Russian exposures: let’s say the direct exposures to Russian counterparts, Ukrainian counterparts, are not a major cause for concern. The exposures are overall contained, but of course when there are tensions and when there is the possibility of sanctions floated, of course this is an issue that raises concerns. We need banks to prepare. Our teams contacted the banks and asked them to investigate which type of assessment they were making and which preparations they were making.

On cyberattacks, let’s say again: our push on banks is a general push to increase their defences. We have seen an increase in cyberattacks in 2020 in particular, but in general the number also remained above pre-pandemic levels in 2021. So it is an issue in general in which banks need to strengthen their defences.

On the business model: I’m sure you have some bank in particular in mind which escapes my attention! Anyway, let’s say it is not up to us to define which business lines the banks should focus on. What we are telling banks is: you should understand which area of business is your strength, which area of business is instead not generating a sufficient stream of profits in the medium-to-long term, and focus your business on those areas which are generating income in the medium-to-long-term perspective. So they need to do this work of repositioning themselves. That’s crucial, that’s what we are trying to push them on. We are supervisors; we cannot drive their car, so they need to… It’s up to the management and, eventually, to their shareholders to decide where they need to put their focus. There are banks which are specialised, which are focused on specific segments of business, and very effective in doing so. So we don’t have any preclusion to that.

I have two questions specifically about Portuguese banks. What is your view on the behaviour of these banks in 2021? And also, how do you see the situation surrounding the CEO of Novobanco?

I am sorry, you know that first of all I dislike giving comments on a country’s banking sector. I do it sometimes when I do country visits, but especially in this type of conference, I tend to focus on the big picture of European banks more than national banks. I would focus even less, of course, on individual cases. The only thing I would say is that whenever there are new reports on challenges and concerns reflecting individual banks, you can be sure that our teams are following these issues closely. Maybe the other thing that I would say is that in general, I mentioned this already before, but in general banks that have been hit particularly hard during the past crises – the great financial crisis, the sovereign debt crisis – in terms of asset quality and that was the case for Portuguese banks, as well as for Spanish, Italian, Irish and Greek banks. In all these cases, there has been significant improvement in recent times.

I was concerned. To be honest, if you asked me a year-and-a-half ago when the pandemic struck, I was concerned that this would have interrupted the improvement in the cleaning of the banks’ balance sheets and strengthening the banks’ balance sheets. This instead has not happened, and I view this very positively.

Could you just talk to us a bit more about what you’d like to see the banks doing to prepare for potential increases in cyberattacks? Also, could you talk to us a bit more about what you want to see the banks doing to prepare for a likely increase in interest rates? That seems to be one of the supervisory concerns that you’ve raised. What can banks do? Normally rising interest rates is actually good for banks because it increases their net interest margin. But where do you see the risks as interest rates rise?

On cyberattacks: I mentioned this a bit in my introductory remarks. Let’s say the issues are mainly… what my team tells me is that what is crucial is especially basic cyber hygiene measures and investing sufficiently in terms of staff. We know that experienced staff in this area are more and more difficult to find, but having the right staff and training the broad staff in this respect is particularly important. Another point which we are focusing on a lot is the fact that banks could also have important and effective security measures. But then if they outsource critical functions to a third party and these third parties are taken offline by a cyberattack, then they should be able to continue providing their services. So they need to cover also for these aspects. In general, let’s say, we have also been promoting, sometimes even sponsoring, and asking banks to perform so-called red team tests. Penetration testing is also a key ingredient in the cyber protection and the cyber preparation that we ask from banks.

In terms of the increasing interest rates, of course you are right – the perspective of a gradual and smooth exit from the low interest environment is, in general, a positive for banks, especially if coupled with strong and continued growth, because that would imply higher interest margins from a steeper yield curve. It would imply greater lending volumes from increased demand. So, in general, we see that also markets discount the probability of higher interest rates in perspective as a positive for banks. Having said that, of course there is also a differential impact across banks according to their business model. Some banks could be more impacted than others by downward revisions in some valuations of assets. Some could suffer maybe from their customers having more difficulties in paying back their debt. The point on which I focus more is not so much the increase in interest rates in itself, but the risk of having sudden shocks, surprises, unexpected developments, credit spread shocks which could hit particularly the fringe areas of the banks' portfolios where they maybe took excessive risks. So especially in exposures to non-bank financial institutions, to highly-leveraged segments of the clientele, to areas which are particularly exposed to concentration risk and high leverage.

We saw elements of this in the spring of 2020. When the pandemic struck there was a significant impact in some segments of the market: equity derivatives, leveraged lending. It was thanks to the strong support measures that these segments of the markets did not create excessive pain for the banks. So, these are the areas and the instances where I think that banks should focus their attention.

The first question is on the options on the table that we hear about to react to a hypothetical Russian invasion of Ukraine. Out of these options, S.W.I.F.T. has been mentioned. Maybe it is not on the table, but can you give us an idea of how disruptive it could be if a message payment system with a global business was involved?

My second question goes back to interest rates, but focusing on the specific impact that downgrades or credit risk could have on government bonds. I know that you look forward to banking union progress. You always mention that, and maybe this year there could be progress, but maybe the government bond holdings are going to slow the process – just because this year, we could have price corrections.

Again, as you say, there has been mention of potential sanctions and even the idea of interventions on payments. Of course, any intervention that affects S.W.I.F.T. payments would be the most impactful. If I remember correctly, that is something which has only been done in one case, for Iran, in the past, so it's a very extreme measure. In general, I think that banks need to prepare and banks are doing their preparation. If any type of sanction will be issued, banks will have to make sure that these sanctions are properly applied for all counterparts they have their business with. It is very key from our perspective as supervisors that we make sure that this is indeed the case.

On interest rates: again, for the time being, as I mentioned, we see the developments as gradual and smooth, so mainly on the positive side. We think that, in general, there is no aspect that concerns us. Yesterday we had a regular meeting with a market contact group in which we meet with investors and analysts and try to get a little bit of market intelligence. We were maybe positively surprised to see how upbeat some of the comments were in terms of how the potential developments in interest rates would be for European banks.

You mentioned climate change being an area in which you'd provided recommendations to banks. It had previously been suggested there could be quantitative add-ons under Pillar 2 this year for climate change risks. Could you confirm whether that happened and what areas the qualitative recommendations that you made were in?

Frank Elderson: I will take this question, thanks a lot. Indeed, climate change, and banks’ management of climate-related and environmental risks, is one of our key priorities for the coming years. To just take a small step back, more than a year ago we published our expectations. Last year was a year in which we asked the banks to actually look at how they self-assessed themselves against these expectations. There was good news: banks were very forthcoming and very open. There was bad news, and that was that banks generally do not comply with our expectations. So, we sent letters to the banks, we asked for action plans and this year will be the year which I will describe as the one where the rubber hits the road. I think as the Chair said very well in the introductory statement: we expect banks to take real actions.

Now, what will we do? We will have a micro stress test, as you said. On the one hand it’s true, this micro stress test is still a learning exercise. It is not a pass or fail exercise, it is not a capital exercise, it's a learning exercise for us as a supervisor and for the banks. As we have said repeatedly, and let me say it here as well: there are no direct – and the Chair said as well – there are not going to be direct capital consequences. It might be that indirectly, via the scores, there might be effects on Pillar 2 requirements but these, if any, will be indirect. It is true that, apart from the stress test, we will also have a thematic review and all these results will feed into the SREP. They already did to a certain extent this year. They will do so next year and gradually climate-related and environmental risks will become more and more part of our regular dealings with the banks and will have effects on how we look at the various risks that climate and environmental risks translate into.

A quick question on the follow-up on leveraged loans: you mentioned that next year could be a time where you're going to perhaps make some requirements on capital related to leveraged loan exposure for some banks. I just wanted to clarify, though, that it seems like that has already been done – I know of one bank at least this year. So there are banks that were already increasing their capital – selling some of their capital because of leveraged loan exposure – is that correct? I think Deutsche Bank mentioned that in the second quarter result last year.

Then the second question is on inflation. Interest rates are supposedly great for banks but it's coming on the back of high inflation. Are you worried about anything related to high inflation and how that can impact banks, from cost to salaries and things like that?

Andrea Enria: I will not comment. Of course, we give individual results on the overall SREP outcomes, but we do not comment on the individual measures for individual banks. Again, what I described to you in response to a previous question is an escalation process that we have with banks. We first set out the guidance, the expectations. We see how the banks measure against this yardstick and if we are dissatisfied we start asking for changes. If these changes do not materialise then we start asking in a stronger way and eventually, if nothing changes, we start activating our measures also in terms of capital charges. That's exactly the type of progression that we are following on leveraged finance, as for other areas.

On your other point on inflation. I read a paper recently saying that we expect that now the bulk of people operating in banks have never experienced a period of inflation in their professional lifetime. So, it is something that we will have to see what the impact will be. There could be different channels through which inflation impacts banks' balance sheets. For the moment we don't see pressure on the cost side, but of course that's an area that will need to be kept under control. More generally, I think that the greatest issue will be whether there will also be an impact on growth. You need to look at the triad: inflation, interest rates and growth. As long as you have an impact via a smooth increase in interest rates, and growth remains as it is currently expected – strong for the next three years – I think that the impact is going to be broadly positive. These are the main areas right now, but indeed there could be aspects that might require greater attention.

We have seen that inflation and inflation differentials are also driving different paths in monetary policy in different jurisdictions. This could also imply, for instance, that in some emerging markets there could be disruptive developments that could impact banks through that channel. So there could be a number of channels we might have to focus our attention on going forward, but in general the baseline for us is that there should be a positive development.

I have two quick questions. One is on TLTRO III: I was wondering if you think this instrument is still necessary, given the fact that there is no real lack of willingness to lend and given the banks' recent good figures.

The second question is that you mentioned there is still bad governance in banks. Has this got worse and do you see it all over the place, or in some countries? Is it a problem that you see all over the place?

On the TLTROs, this is probably the wrong press conference to ask about it – it's more a monetary policy measure. My understanding is that the expectation is that these will expire next year, if I remember correctly. So from our point of view as supervisors, we will only look at the effect this might have on bank funding. Banks have probably been benefiting on the funding side in recent years from the extraordinarily accommodative monetary policy. So, in the future we think that banks will have to devote more attention to their funding plans, and we will follow that.

In terms of bad governance, I definitely don't see country patterns. It's an issue that is quite widespread and the point which concerns me is that we have seen this persisting. It's very difficult to have correction through time. I understand it is difficult, because to change the composition of the board you need to have succession and the like. Again, the key point that I mentioned also in my introductory remarks is that banks needs to focus on this. They need to develop succession plans, make sure that they have the right composition of the board, the right interaction between the supervisory and the management function, the right role and the staffing and status of the second line of defence. These things are crucial, and we will keep insisting on that. Eventually also in this area we will have to find our proper escalation processes when banks don't react as we want them to.

A follow-up on sanctions: for banks that do have Russian exposures, can you explain what kind of steps you're asking them to take to prepare for sanctions but also for a possible S.W.I.F.T. intervention?

There is often a focus on direct exposures. First of all direct exposures, as I mentioned before, are relatively contained. Second, in many cases they are also accompanied by local funding, so they are not as relevant as a source of risk. In my view, the concerns from a supervisory perspective in the event of a deterioration of tensions between Russia and Ukraine is more in the area of potential sanctions and the role that banks might have in ensuring that these sanctions are properly enforced, and the possible broader turbulence in financial markets. These are the two main areas in which I would see supervisory concerns. For banks, when you also have ownership links and the like, you need to make sure that in the event of sanctions there would be a proper follow-up. These are the areas in which our teams are approaching banks and asking for proper preparations to be made.

- ECB Financial Stability Review, 17 November 2021.

- See, for example, “Report of the High-Level Group on Financial Supervision in the EU”, 25 February 2009.

Banco Central Europeu

Direção-Geral de Comunicação

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Alemanha

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

A reprodução é permitida, desde que a fonte esteja identificada.

Contactos de imprensa-

10 February 2022