- SPEECH

The many roads to return on equity and the profitability challenge facing euro area banks

Speech by Andrea Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the 26th Annual Financials CEO Conference organised by Bank of America Merrill Lynch

Frankfurt am Main, 22 September 2021

Introduction

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to take part in today’s very important conference and to address such a broad and comprehensive audience of financial market participants. I would like to focus my remarks on European banks’ profitability and business models.

Supervisors are neither bankers nor consultants. It is not our job to make decisions about banks’ business model strategies, corporate structures, business lines or risk appetite. Why then, do we venture into discussing the finer details of the quest for profitability?

Banks’ profitability is a key driver of capital strength, financial stability and resilient financial intermediation. First, organic profits are the first line of defence against shocks to the economy. Second, banks’ ability to raise capital when needed depends on their profitability. And third, unsustainable business strategies, such as gambling for resurrection or unhealthy pricing competition among banks, lead to an altogether riskier banking sector, threatening financial stability.

Whatever choices they make, banks need to ensure their business model performance is sustainable throughout the cycle, including in challenging business environments, such as those that followed on from the great financial crisis, the sovereign debt crisis and, more recently, the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

However, European banks have actually been struggling with low profits for more than a decade. In my speech today, I will review the cyclical and structural hurdles that have contributed to this. I will argue that the pandemic shock has prolonged the pressure on interest margins but has also created favourable conditions for a more radical revamping of business models and for restoring profitability to sustainable levels.

What levers do banks have to try and enhance their profitability? And are they pulling the right ones?

Asset quality has been a drag on European banks’ profitability for quite some time. We are glad to see that more decisive action has been taken in recent years to resolve the burden of legacy non-performing loans (NPLs). The massive progress achieved should not lead banks to lower their guard on credit risk, as the actual impact of the pandemic on asset quality has not yet become apparent. A recovery in profitability based on a sharp and sudden reversal of provisions might not prove durable if the optimistic expectations of banks do not materialise and, as public support is gradually phased out, the risk environment turns out to be worse than currently expected. Many banks have been longing for a normalisation of the interest rate environment as a panacea for restoring profits. It is now clear that the pandemic has extended the time frame for that adjustment. And even when it does occur, the new normal won’t look like the old normal. The digital transformation has accelerated during the pandemic and is changing the competitive landscape for good. Environmental, social and governance risks are growing in importance, reshaping the business environment and impacting on business strategies. At the same time, the regulatory overhaul that followed the great financial crisis rules out strategies boosting leverage and pursuing risk taking as shortcuts to achieving a higher return on equity.

The only serious way to address and win the profitability challenge is to take decisive action towards enhanced cost efficiency and to refocus the business model towards longer-term value creation opportunities. And this is where I become more optimistic. My take is that beyond what can be seen in the aggregate data on cost efficiency, which admittedly tells the story of sticky inefficiencies, there have been recent signs of concrete improvements, and more changes seem to be occurring than is generally acknowledged. Where there has been healthy pressure from shareholders combined with focused strategic steering from managers, we have seen more ambitious cost reduction programmes and transformation plans taking shape. The fact that upfront transformation costs have to be borne implies that results are often not yet visible in profit and loss (P&L) outcomes. But, with some delay, tangible improvements in cost efficiency and profitability can be achieved.

Bank mergers and acquisitions (M&As), generally considered the boldest and most transformative type of adjustment, seem to have gained some momentum in 2020 despite the pandemic. Beyond what we can see in aggregate M&A data, some banks have also engaged in more targeted consolidations at the line of business level as well as in other forms of business model optimisation. In the areas of asset management, custody and settlement services and payment technology, some players have been expanding or diversifying while others have been downsizing in order to redirect resources and refocus. Fully-fledged bank M&As remain predominantly domestic, but some of the more targeted transactions feature a cross-border dimension, thus also contributing to financial integration within the EU.

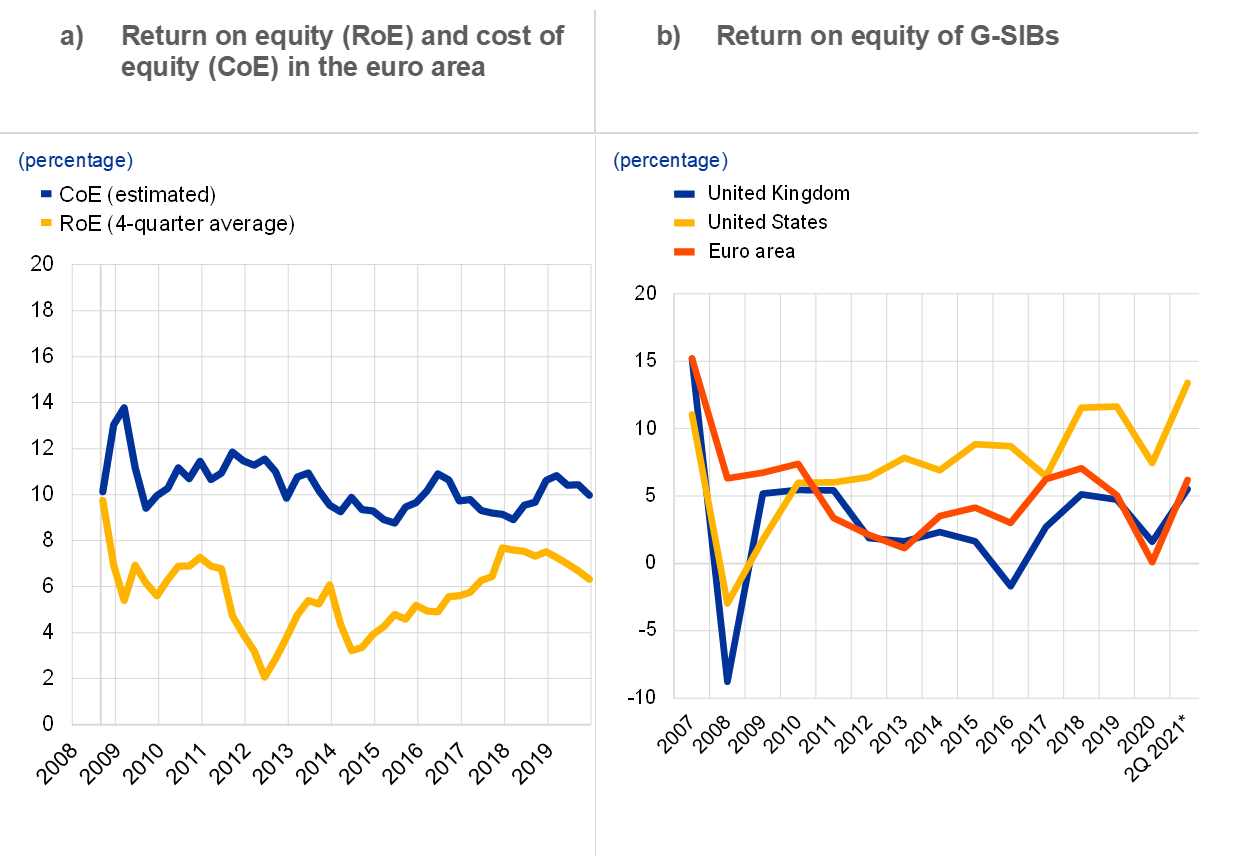

At the root of a long-lasting challenge

The profitability of euro area banks has come under significant pressure since the great financial crisis of 2007-08. Return on equity (RoE) hit its lowest point at the peak of the European sovereign debt crisis and took several years to stabilise at the 6%-7% average values observed during 2017-19 up until the pandemic shock. Absolute RoE values prior to the great financial crisis are not necessarily a good benchmark, as they stem from far lower capital levels than those we are seeing today, as well as attitudes and practices that no one wants to see return. However, as research published by the ECB[1] shows, the great financial crisis does represent a structural break in that, since it occurred, the average euro area bank has been unable to earn the sector’s estimated cost of equity, which is commonly used to measure the compensation investors demand for investing in and holding bank equity (Chart 1, panel a).

A look at the comparative performance of global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) across jurisdictions shows that the post-crisis profitability adjustment has been steadier and somewhat faster in the United States than in Europe (Chart 1, panel b), although this trend can also be explained by EU-specific sovereign debt crisis events.

Chart 1

Panel a):

Sources: Bloomberg, Refinitiv, Kenneth R. French data library, S&P Market Intelligence and ECB calculations.

Note: the latest observation is for December 2019.

Panel b):

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB calculations.

Note: Q2 2021 data are annualised.

There is a general consensus regarding the key factors that have contributed to keeping the average profitability of euro area banks at unsustainably low levels for longer than a decade.

Two of these factors are cyclical in nature: the deterioration in asset quality caused by the financial and sovereign debt crises, and the low interest rate environment that prevailed after both crises. NPLs are a drag on banks’ profits because: i) they generate less income than performing loans; ii) they attract higher loan loss provisions; iii) they tend to be associated with higher funding costs; and iv) they divert capital and operational resources away from more productive areas. The impact of persistently low interest rates, however, is more complex to disentangle. Although banks’ interest margins have been compressed, lower rates may simultaneously have had an overall positive effect by supporting banks’ lending volumes and trading book valuations while keeping impairments at bay[2].

In addition to cyclical forces, a set of structural factors have played a major role in constraining the profitability of EU banks over the last decade. First, EU banks inherited a heavy and costly branch structure put in place as part of the pre-crisis expansionary cycle, characterised by high costs for staff and premises and limited cost efficiencies. Second, due to a multiplicity of factors, including institutional and regulatory features, the sector proved unable to generate a systematic healthy flow of bank consolidations and market exits. As I have discussed on previous occasions, a much lower number of banks were resolved or liquidated in the EU than in the United States in the wake of the financial crisis. In addition, there were very few consolidations in the EU during the same period. As a result, the European banking sector is still suffering from an enduring excess capacity problem and currently remains less concentrated than in the United States. When it stems from weak and unprofitable peers, competition can be at the root of unsustainable pricing practices and other unhealthy business dynamics, which contribute to eroding the profitability of the whole sector and tend to feed risk. In this regard, the review of significant institutions’ underwriting standards[3] published by the ECB in 2020 found some evidence of loan mispricing. This was evident in particular in the weak correlation between loan spreads and levels of expected losses across exposures belonging to the same portfolio, and instances of loan spreads not high enough to cover those losses.

In addition, European banks have had to face forms of competition other than those stemming from an overly crowded market of traditional banks. The steady increase in the population’s access to internet services and use of electronic money since the early 2000s has significantly changed the banking environment. Digital banks and fintech companies have been entering the traditional banking arena as well as other new markets for digital financial products and services.

Unsurprisingly, some of the fundamentals that have weighed on the profitability of the banking sector have also contributed to shaping investors’ risk perception about banks and therefore the rate of return they seek on bank equity investments. Research published by the ECB[4] shows that, based on data from 2008 to 2019, NPL ratios, the relative reliance on interbank and therefore less stable funding sources, and cost-to-income ratios are all statistically significant drivers of the euro area estimated cost of equity.

Banks are starting to pull the right levers: greater focus on structural transformation is the only sustainable way forward

In the face of these cyclical and structural challenges, there is some evidence that a number of banks are finally starting to pull the right levers and to drive the necessary structural transformation of their business strategies. Let me elaborate on how the different challenges are playing out.

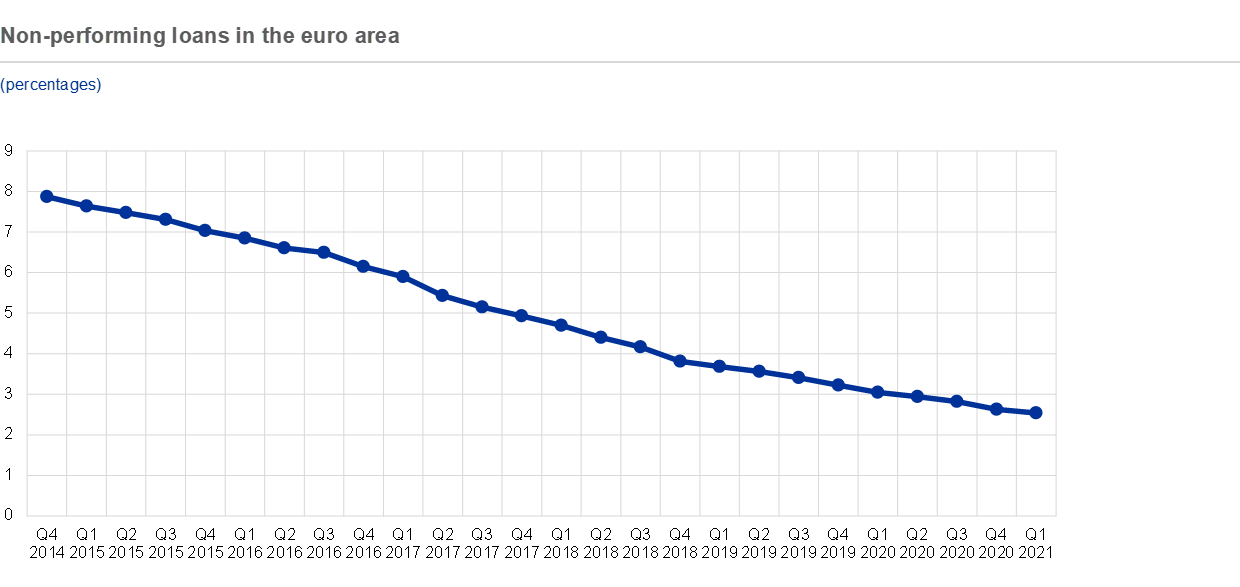

Cyclical challenges: the old normal may never return

Since the Single Supervisory Mechanism was established, euro area banks have made tremendous efforts to resolve legacy credit risk. At the end of the first quarter of 2021 the NPL ratio of banks under ECB direct supervision stood at 2.5%, down from approximately 8% at the end of 2014 (Chart 2), with the bulk of the outstanding volumes concentrated in a few jurisdictions hit particularly hard by the financial and sovereign crises. Behind the average metric, the “high NPL banks” – i.e. institutions overloaded with above average levels of bad loans – continued to make very good progress in resolving legacy risk, including during 2020, despite the turmoil caused by the pandemic.

Chart 2

Source: Supervisory reporting.

Note: varying sample.

If we were not halfway through a delicate recovery phase and coming out of a crisis whose NPL legacy is still not clear, I would be tempted to say that NPLs no longer represent a widespread burden on the profitability of our banking sector. But it is clearly too early to lower our guard. The pandemic-induced freeze on economic activity initially dealt a major blow to banks’ profits: the RoE hit bottom at 0.01% in the second quarter of 2020, down from 6% the year before (second quarter of 2019) owing mainly to increased impairments of financial assets (Chart 3, panel a). Against the backdrop of a continuous improvement in the macroeconomic outlook and ongoing measures by national governments to support the economy, most banks have started reducing their impairment levels. In the first quarter of 2021, driven by the reduction in impairments, the sector’s RoE bounced back to 6.1%. Banks seem to be dismissing the possibility of a material deterioration in asset quality in the wake of the pandemic: based on their projections submitted at the beginning of the year, the NPL ratio will keep decreasing over the next two years (Chart 3, panel b) and impairments will return to pre-pandemic levels by 2023 (Chart 3, panel a).

As supervisors, we remain highly focused on monitoring banks’ credit risk management and control practices as the economy gradually recovers from the pandemic. In our view, banks should refrain from using overly optimistic assumptions on the asset quality trajectory to portray rosy short-term profitability prospects.

Chart 3

Panel a):

Sources: FINREP, EBA funding plans.

Notes: balanced sample of 93 significant institutions (SIs). Overhead costs are the sum of staff expenses, other administrative expenses and depreciation. For comparison purposes, overhead costs in 2018 and 2019 are adjusted for cash contributions to deposit insurance schemes using the 2020 level of these contributions (around €8.9 billion).

Panel b):

Source: EBA funding plans.

Note: balanced sample comprising 91 SIs.

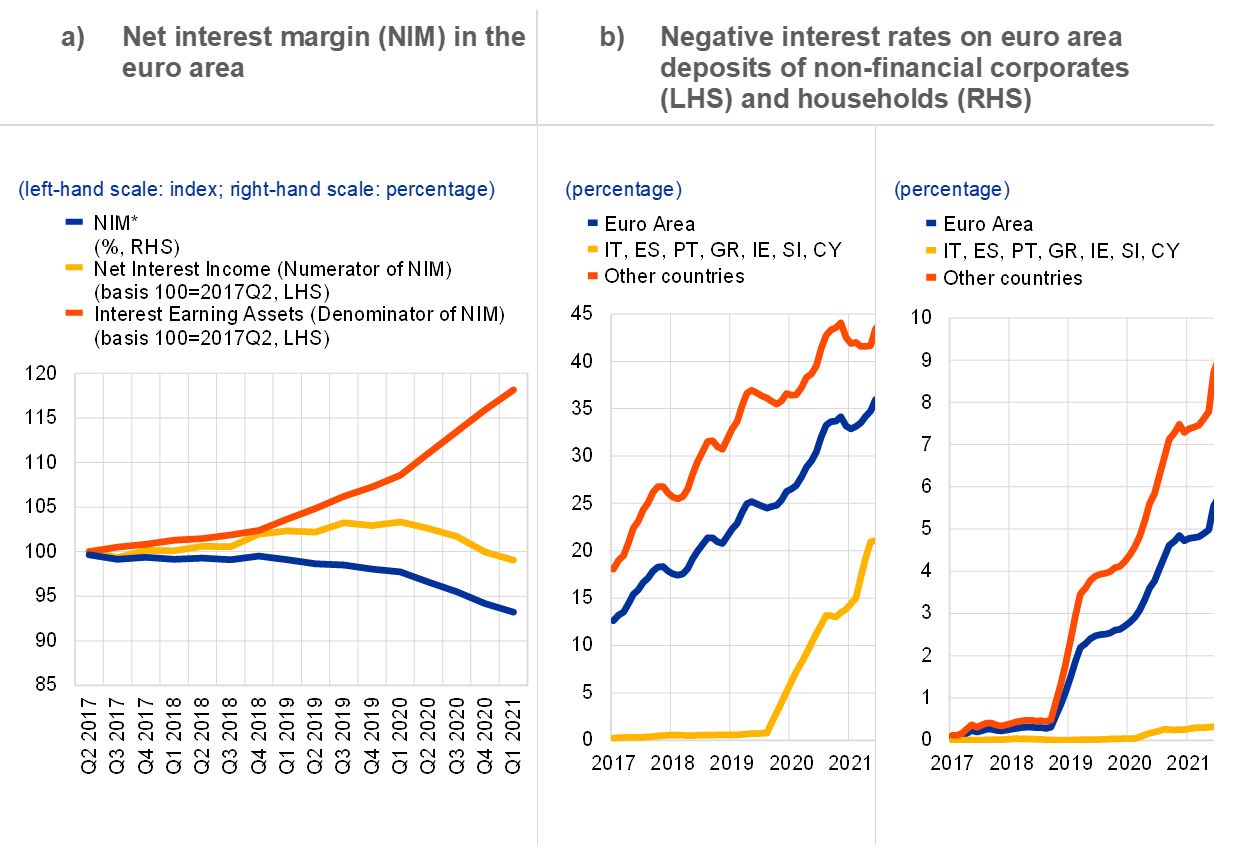

Before I turn my attention to the topic of structural transformation, let me briefly elaborate on banks’ income-generating capacity during challenging phases of the business cycle.

Available evidence shows that since 2020, the already slim bank interest margins have come under intensified pressure (Chart 4) despite the positive effects of the accommodative monetary policy stance in terms of higher lending volumes and support for borrowers’ repayment capacity. In fact, thanks partly to public loan guarantees, lending to the real economy by significant institutions has increased overall by more than 4% since the end of 2019[5]. However, this was not enough to offset the impact of the pandemic in terms of supporting net interest income, which has been falling ever since (Chart 4, panel a).

For quite some time, many banks maintained “wait-and-see” approaches, pinning their hopes on a rapid normalisation of the interest rate environment. The COVID-19 pandemic and the strong policy response to limit its economic impact have now led to the broader realisation that banks will have to operate in a low interest rate environment for some time to come. Banks have been increasingly passing negative rates on to customer deposits (Chart 4, panel b), but it is clear that this will not be a panacea.

Other sources of income, including trading and fee and commission-generating activities, have proven more resilient to the shock for most business models. This highlights the resilience of business diversification strategies.

Chart 4

Panel a):

Source: FINREP data.

Notes: Constant sample of 94 SIs. Annualisation: rolling four quarters.

Panel b):

Sources: ECB (iMIR, iBSI) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Deposit rates on outstanding amounts as reported by individual banks for each of the available product categories weighted with the respective outstanding amounts. Household deposits include deposits from private households (in line with the European system of accounts (ESA) 2010, S.14) and deposits from non-profit institutions serving households (S.15, ESA 2010). The latest observation is for July 2021.

Another illusory avenue to boost the return on equity is the hope for some relaxation of regulatory standards, which would enable banks to operate with lower levels of Common Equity Tier 1 and adopt a riskier profile. The debate on the implementation of the final elements of the Basel III reforms reflects quite a unified stance by the supervisory community, which is opposed to a looser or delayed application of standards that are essential to ensure the reliable and consistent calculation of risk-weighted assets.

The pandemic also revealed that when uncertainty spikes and market volatility reaches abnormal levels, myopic shortcuts to profitability based on excessive leverage and complexity become sources of material losses. In this instance, I am referring to the losses that some banks suffered on complex structured equity derivatives at the onset of the pandemic. Equally revealing were the significant losses incurred by a few global prime brokers as a result of the insolvency of Archegos, a firm in the family office sector. I have on previous occasions warned against the disruption that the risky segments of the credit and equity business may cause, if, for example, investors’ expectations regarding the path of inflation and interest rates suddenly change, bringing about widespread corrections in asset prices.[6]

The pandemic has also accelerated a structural change in the competitive environment in which banks operate, as the wider acceptance of digital tools for payments and financial services has significantly enhanced the ability of new entrants to eat into incumbents’ profits at different points along the value chain. Banks need to engage in bolder, forward-looking structural change for the sector to thrive on a more sustainable basis.

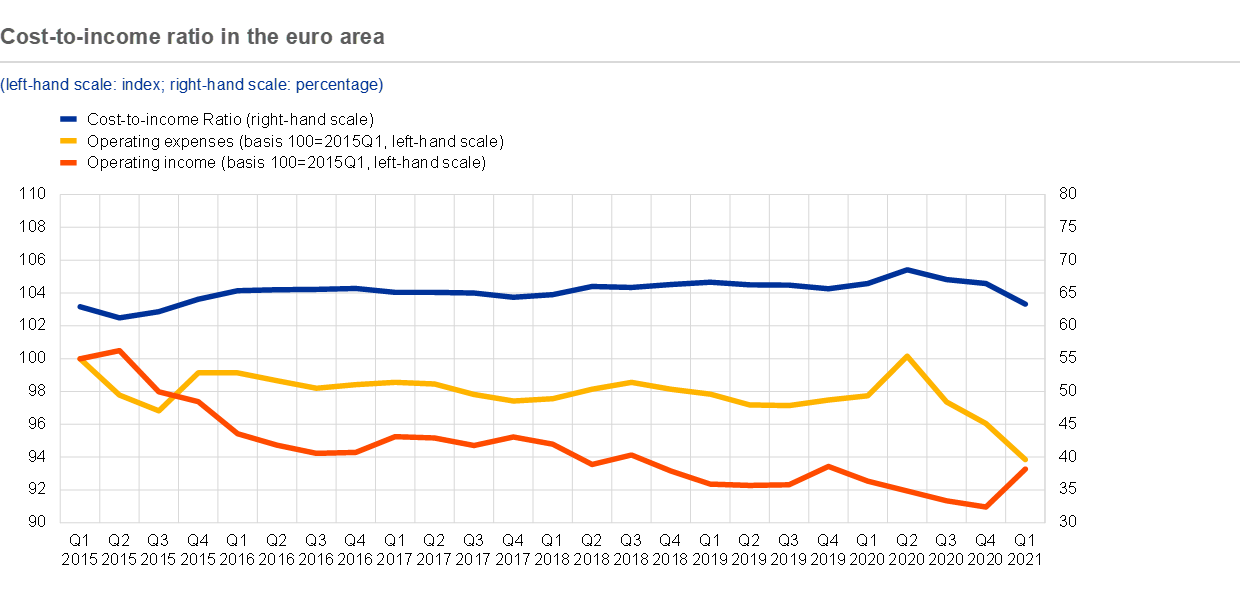

Structural transformations: beyond cost reductions, banks need a strategy for value creation

The aggregate dynamics of the cost-to-income ratio (CIR) since 2015 (when supervisory data started to be submitted to the ECB) tell the story of an enduring inefficiency problem. The average cost-to-income ratio has been fluctuating around 65% without showing any lasting signs of improvement, with operating income falling as fast as operating expenses (Chart 5).

Chart 5

Source: FINREP data.

Notes: Constant sample of 84 SIs. Annualisation: rolling four quarters.

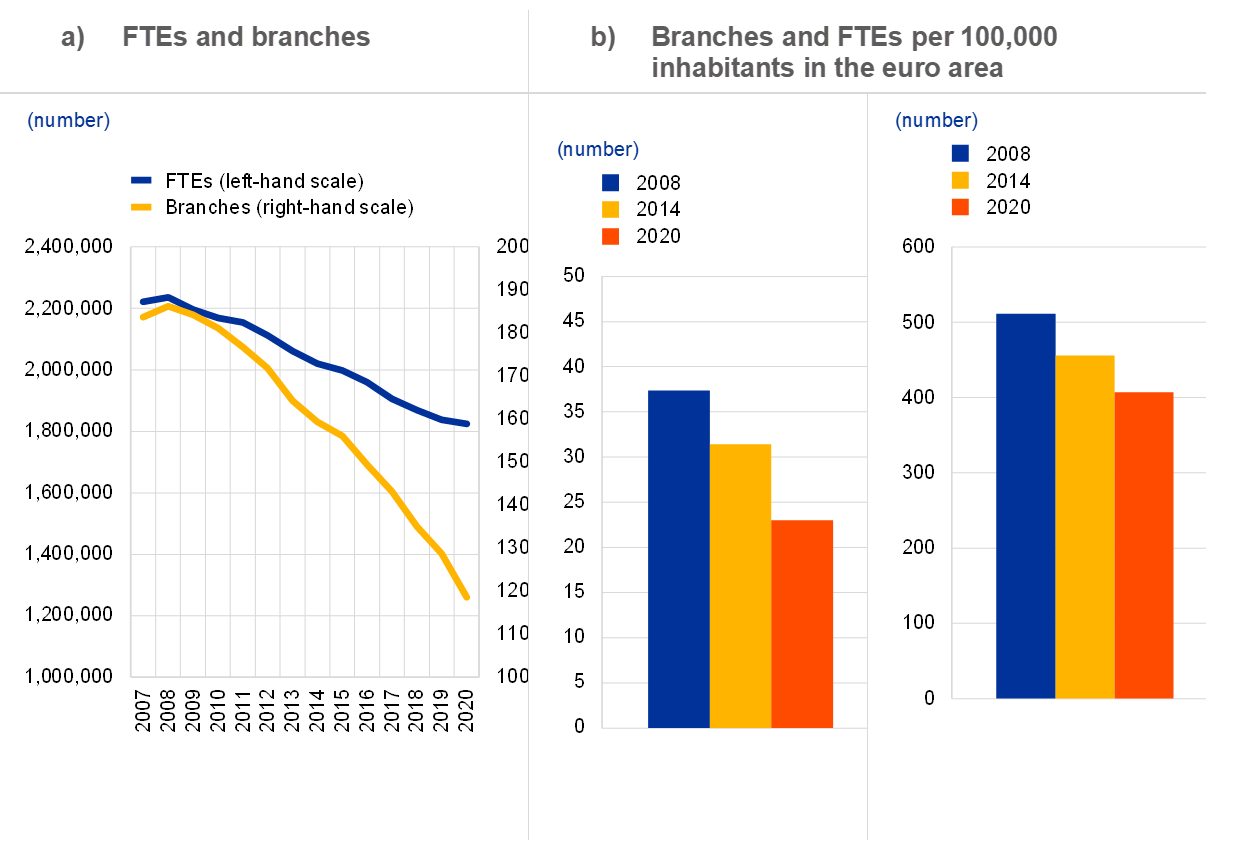

The euro area sector as a whole has continued to work towards reducing staff and branch expenses. These notably account for a high share of banks’ operating expenses[7], and are the first concrete quantitative metrics we look at when analysing cost efficiency. Between 2007 and 2020 the number of full-time equivalent positions, or FTEs, fell by around 18%, while branches were cut by around one third. According to market research, only a few euro area banks achieved very substantial branch reductions, ranging between 50% and 80%. In 2020 the euro area banking sector operated with 23 branches per 100,000 inhabitants, down from 37 in 2008, and 407 employees per 100,000 inhabitants, down from 511 in 2008 (Chart 6).

Chart 6

Panel a):

Source: ECB.

Note: varying sample.

Panel b):

Source: ECB.

Note: Both number of branches and population are sourced from the ECB Data Warehouse (SSI: Banking Structural Financial Indicators; number of employees, euro area (changing composition), domestic (home or reference area), breakdown by country).

Many view these as slow moving dynamics, especially given the excess capacity generated in the run-up to the great financial crisis and the hopes that markets have been increasingly placing on the digitalisation of the banking business as a way to reduce front, middle and back-office headcount and cut down on branch banking. Some analysts maintain that large banks are only halfway through their post-crisis branch reduction journey and that FTEs should be reduced much further.

What is it that is making cost efficiency so sticky in the euro area? Will further reductions in staff and branch expenses, in isolation, turn this around?

Part of the problem indeed stems from a fairly large number of banks that haven’t yet taken any material measures to bring costs down. As I mentioned earlier, similar “wait-and-see” strategies are in my view bound to fail and, in this vein, I fully support market analysts’ calls for the sector to focus chiefly on reducing costs.

However, there could be more to it than simple cost cutting. Some banks may have hastily focused on reducing expenses and laying off staff without sufficient strategic steering towards value creation and income-generating capacity. These choices suggest little awareness of the fact that structural cost savings mean investing in structural transformation.

This is in line with the main findings of a thematic review on profitability and business models that the ECB conducted between 2016 and the first quarter of 2018.[8] Costs, taken in isolation, are not the decisive factor behind a positive profitability performance; reducing costs can be ineffective without long-term strategic steering.

Several banks have recently taken the route of comprehensive and tech-driven cost optimisation programmes, often in the context of wider plans to structurally refocus their business models. Most banks in this last category, moving in the right direction, inevitably incur material upfront transformation costs of a one-off nature and typically see the expected gains from their investments materialise only some time after execution. Although this contributes to making their cost-to-income ratios sticky, it does eventually deliver long-lasting improvements in profitability.

The features of the cost reduction programmes of each bank are thoroughly analysed by our joint supervisory teams. Prior to the pandemic, we ran an in-depth horizontal assessment of a handful of cases, covering institutions of different size, business model and geographical location. Among these, some did manage to bring their cost-to-income ratios down considerably as a result of cost cutting, even achieving double-digit percentage-point reductions. The review revealed that a consistent set of key factors might be among the drivers of a successful transformative cost reduction programme.

One of those factors concerns the governance of the cost reduction programme, including the presence of qualified and highly motivated management, the development of a clear cost reduction strategy and a good level of internal communication on the strategy itself. Another success factor consists of having detailed knowledge of the cost/income structure of the bank’s business. This includes the ability to safeguard existing costs that are essential for the income-generating capacity of the bank, and costs that are essential to ensuring that the internal control, risk management and compliance and audit functions continue to perform properly. There should also be a forward-looking focus on key “transformation costs”, for example in the area of digitalisation. Transformation costs are costs that are instrumental in preparing the bank for a more cost-efficient steady state, as well as costs that enable the bank to gain additional sources of income. Other success factors include investment in IT and process optimisation, including initiatives and investments for simplifying and digitalising processes. A cost reduction programme should also include labour market considerations, including the legal framework for reducing FTEs and the instruments available to manage that process.

Bank M&As: encouraging signs of a rebound in bank consolidation in Europe

Wider structural transformations, which may not only bring cost reduction and cost efficiency, but also growth and diversification, often entail consolidation strategies.

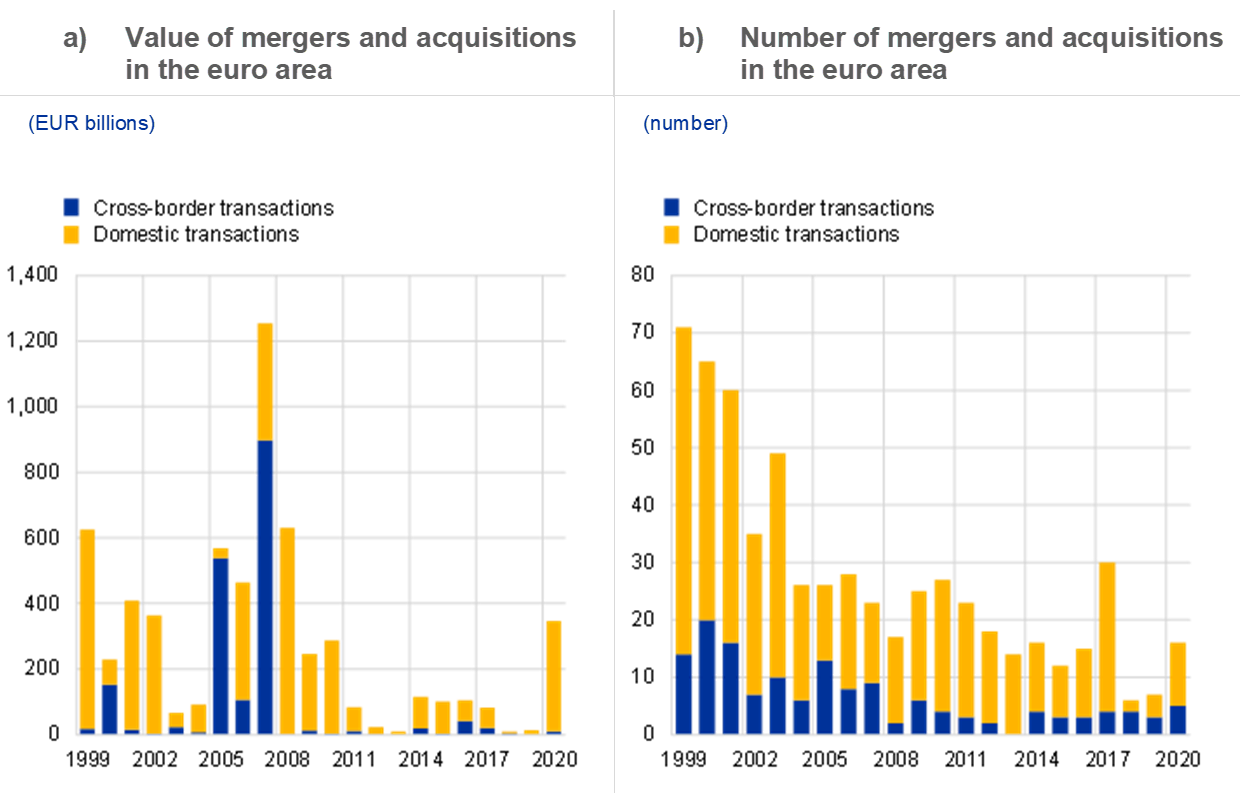

We have long discussed the subdued dynamics of bank M&As in the EU. As we remain focused on the need to eliminate any potential supervisory obstacle to these transactions[9], we should take comfort in the fact that encouraging signs of a rebound in bank consolidation have emerged from 2020 data. Indeed, the pandemic has brought about levels of consolidation not seen since 2008, with transactions worth more than €300 billion (Chart 7). Some of these transactions, for instance in Italy, Spain and Slovenia, increased the level of concentration of the respective national banking markets considerably and should allow the entities involved to see cost efficiency improvements in the years ahead as a result, inter alia, of the existence of overlapping distribution networks.

Chart 7

Sources: ECB calculations based on Dealogic and Orbis BankFocus

Notes: Transactions associated with the resolution of banks and distressed mergers were removed from the sample. Transactions are reported on the basis of the year in which they were announced. Total assets refer to the target’s total assets.

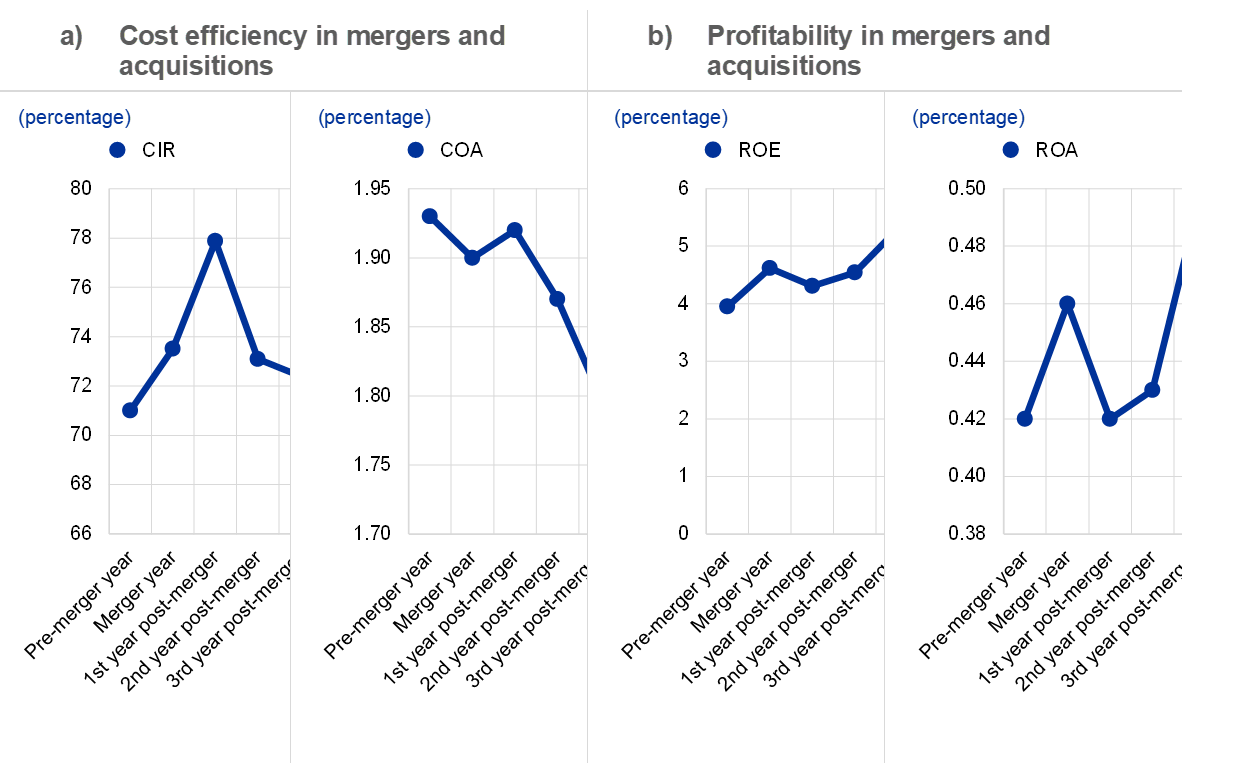

Even more than cost-cutting programmes, M&As entail high one-off restructuring costs and tend to deliver gains with some delay. According to evidence we have gathered on a large number of M&As among less significant institutions during 2015 and 2016, the average consolidation project delivers on cost efficiency and profitability only two or more years after it is implemented (Chart 8).

Chart 8

Source: ECB

Note: Based on year-end data for a sample of 150 less significant institutions (LSIs) that acquired another LSI in 2015 and 2016. COA refers to overhead costs over total assets.

Aggregate statistics on bank M&As do not enable us to accurately monitor the interesting recent trend of more targeted adjustments to banks’ business models. Some players are acquiring or divesting from individual business lines or fintech infrastructures or are creating joint ventures with other European competitors in specific business areas. These and similar more targeted consolidations are no less important than fully-fledged bank M&As in delivering cost efficiency improvements, value creation opportunities, competitive gains and effective rebalancing of banks’ business models. They are beneficial not only to acquirers but also to sellers, as the latter identify no longer profitable or core markets or lines of business and exit from them, with the aim of redirecting resources towards more sustainable sources of profit. To the extent that such adjustments allow European entities to better face the competition from extra-EU players, they also help reposition the sector in the global arena. Also, more frequently than fully-fledged bank M&As, these targeted consolidations occur across borders, thus adding to the important dimension of financial integration in Europe.

We have seen institutions strengthen their position in the fee and commission income-generating business by, for instance, acquiring asset management, custody or securities services business lines from competitors or merging their businesses with them. By doing so they further diversify their business and they increase the scale of their operations, which is a very important condition for success in these areas.

The pandemic-induced shift away from cash is pushing some institutions to strengthen their position in payment technology, including through the acquisition of payment technology and assets from peers or the rollout of own technology across geographical areas where they are well-established lenders. In some national markets, partnerships among banks are making it possible to successfully face the scale challenge of the payments business. The business of payments acceptance, in particular, has been consolidating substantially in the last few years, with players showing the ambition to build a European franchise in the field. In an area where scale technological investment and know-how are essential, banks seem compelled to reassess their busines model strategies and decide whether to expand or exit. This year, for instance, this seems to be happening within the Greek banking sector, where one after the other, major lenders are offloading their payment infrastructure.

Similar dynamics are playing out in other segments of the banking business, and the list could be long. One last example I could mention, which is particularly relevant from a regulatory and supervisory perspective, is that of the NPL servicing market, where a substantial wave of cross-border consolidations, promoting know-how, economies of scale and scope on a pan-European level, has led several institutions to discard their infrastructure in favour of other more specialised and efficient set-ups.

Supervisory approach to profitability and business model sustainability

Although they operate from different perspectives, at the current juncture supervisors’ and shareholders’ objectives should, in my view, be pretty much aligned. Let me elaborate on this.

In the context of our supervisory review and evaluation process (SREP) we look into banks’ ability to generate profits, including from a long-term perspective, and the risk that this ability may become impaired either because of external factors, such as a challenging business environment and changed competitive landscape, or internal deficiencies, such as inefficient pricing, inappropriate business strategies, insufficient execution capabilities and poor capital or funding structures. In our view, a sustainable business model should allow a bank to generate returns, achieve strategic positioning and remain resilient to shocks throughout the business and economic cycle.

Pressure from shareholders, including active investors such as private equity and hedge funds, has often been an important catalyst in promoting change and turning weak bank franchises around in the aftermath of the crisis. And shareholders will also play an important role in sharpening management’s focus on business transformation in a post-pandemic environment. I am aware that shareholders have been frustrated by the constraints imposed by the ECB and other supervisors on dividend distributions and buy-backs. Now that these constraints have been lifted, there is a reasonable expectation to see pay-outs resuming in a material way. I would like to stress that the ECB does not intend to take a restrictive stance and will limit its interventions to cases in which the proposed payments would not be consistent with prudent capital planning and the continued respect of regulatory requirements. At the same time, I would like to state that at this delicate juncture, bank shareholders should consider putting more focus on long-term value creation opportunities as opposed to immediate pay-out outcomes. I hope to see them engage more and more in a proactive dialogue with managers on the need to identify growth opportunities and ways to refocus business models. These actions require upfront investments but are the only viable routes to sustainable profitability and, linked to that, the recovery of bank stock valuations.

The sustainability of banks’ business models continues to be one of our supervisory priorities. In early 2021 we initiated a campaign of inspections on business models and profitability, covering 11 institutions and various business models and business lines. The campaign will continue throughout 2022 and extend to other banks. It covers four dimensions of profit sustainability: profitability analysis, financial projections, strategy review process and loan pricing. We are assessing a number of aspects, ranging from the management board’s ability to set up a strategy to the institution’s ability to analyse the drivers of profitability, including the detailed allocation of cost and income sources, the components of the bank’s loan pricing framework and the assumptions and scenarios used in the bank’s business plan. Further engagement with banks and supervisory activities are also expected in the area of digitalisation, including the launch of pilot inspections.

Conclusion

As the economy proceeds surprisingly quickly along the path to recovery, despite some persistent elements of uncertainty, we need to think about how the banking sector can best prepare for the “new normal” that will eventually come. The challenge of profitability, or low profitability, is a long-lasting, deeply rooted one. On many occasions we have gathered to discuss the likely causes and potential remedies. This time, however, is different: the unprecedented shock of the COVID-19 pandemic carries with it useful lessons and opportunities for change, which we’d better not let go to waste. Much more remains to be done, but concrete signs of improvement are in sight. With all the tools we have available, as supervisors we remain committed to monitoring and discussing with banks the key challenges and how these should be addressed.

- Altavilla, C., Bochmann, P., De Ryck, J., Dumitru, A., Grodzicki, M., Kick, H., Fernandes, C., Mosthaf, J., O’Donnell, C. and Palligkinis, S. (2021), “Measuring the cost of equity of euro area banks”, Occasional Paper Series, No 254, ECB, January.

- See Altavilla C., Boucinha, M. and Peydró, J.P. (2018), “Monetary policy and bank profitability in a low interest rate environment”, Economic Policy, Vol. 33, No 96, pp. 531-586.

- European Central Bank (2020), “Trends and risks in credit underwriting standards of significant institutions in the Single Supervisory Mechanism”, June.

- See footnote 1.

- If only loans granted in the euro area by all resident banks were taken into account and adjustments were made for loan sales, securitisation and notional cash pooling, the resulting lending growth would be even higher.

- See Enria, A. (2021), “Enhanced outlook and emerging risk in the banking union”, speech at the University of Naples, Frankfurt am Main, July.

- According to Autonomous Research, in 2020 staff costs and branch premises costs at global (including non-euro area) banks represented, respectively, 53% and 7% of total expenses.

- European Central Bank (2018), “SSM thematic review on profitability and business models”, September.

- In January 2020 the ECB published a guide clarifying its approach to the supervision of mergers and acquisitions. See European Central Bank (2021), “Guide on the supervisory approach to consolidation in the banking sector”, January.

Europese Centrale Bank

Directoraat-generaal Communicatie

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Duitsland

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproductie is alleen toegestaan met bronvermelding.

Contactpersonen voor de media