- SPEECH

How can we make the most of an incomplete banking union?

Speech by Andrea Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the Eurofi Financial Forum

Ljubljana, 9 September 2021

The urgent need for progress in banking integration

Ladies and gentlemen,

I am grateful for the opportunity to deliver this address at the biannual Eurofi Forum. We have finally been able to gather in person and, after such a challenging time, it is a relief and a pleasure to see friends and colleagues once again.

This forum has often played host to discussions on the integration of the European banking sector. Industry representatives have frequently complained about the lack of progress towards a European internal market for banking services that is truly borderless. The debate has traditionally focused on issues related to the euro area institutional framework and legislative reforms. But despite the advances towards a more integrated European institutional and regulatory framework, progress has been underwhelming. For many banking products and services, our market remains deeply segmented along national lines.

Today I will focus on the concrete actions we can take to achieve real progress towards a truly integrated prudential jurisdiction within the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and within the current institutional and regulatory environment. And by “we” I mean all of us, supervisory authorities and market participants alike. At the ECB we are fully prepared to play our part, but such progress must also be shaped by sound projects and initiatives by banks.

Some argue that, until a fully fledged banking union with all its three pillars is in place, there is very little chance of integrating the European banking sector and we are condemned to a collection of national banking sectors, even within the single prudential jurisdiction.

But just before the summer break we had a timely reminder of the difficulties in achieving immediate political breakthroughs. After years of protracted negotiations, the Eurogroup failed to reach an agreement on the roadmap to complete the banking union.[1] While I am confident that agreement will eventually be found, we cannot simply stand still while complex political negotiations play out.[2]

Moreover, as already mentioned, the political agreement will take the form of a roadmap, with a number of intermediate targets. Completing the banking union, including a fully mutualised European deposit insurance scheme (EDIS), will take some time.

But, in the meantime, we cannot wait. There is an urgent need for material progress towards an integrated banking sector in the euro area. And considering the delicate role the banking sector has to play in supporting a robust recovery from the pandemic crisis, this is a matter of even greater urgency than in the past.

These last 18 months have been extraordinary for a number of reasons. First and foremost, we faced a severe public health crisis which created extreme uncertainty for the trajectory of our economies and the risks facing our banks. But we also had to deal with a whole host of issues in a very compressed time frame. This could have potentially sown the seeds of further fragmentation in the banking union, with uneven national responses. However, I am very pleased that – for the first time – there has been a completely unified European supervisory response to the challenges that the pandemic crisis has posed for euro area banks. We have taken unprecedented supervisory decisions quickly, in close coordination with monetary policy measures.

We have also seen the banking sector successfully adapt its operations to the unprecedented constraints imposed by the measures taken to fight the pandemic. Banks adjusted to a dramatic increase in the use of technology, in terms of both how they work and how they interact with their customers. This digitalisation also gave banks an opportunity to make their business models more sustainable, increase their profitability and become more attractive to long-term investors. With this in mind, in January 2021 we published a Guide on the prudential treatment of mergers and acquisitions.[3] We clarified how we assess merger transactions so that banks know what to expect from us, and we think these clarifications have had an impact on consolidation in the euro area banking sector. In the past few months, we have directly applied the supervisory principles set out in the Guide to several transactions.

But most consolidation transactions still take place within Member States. The European banking sector remains segmented along national lines, even within the single prudential jurisdiction of European banking supervision.

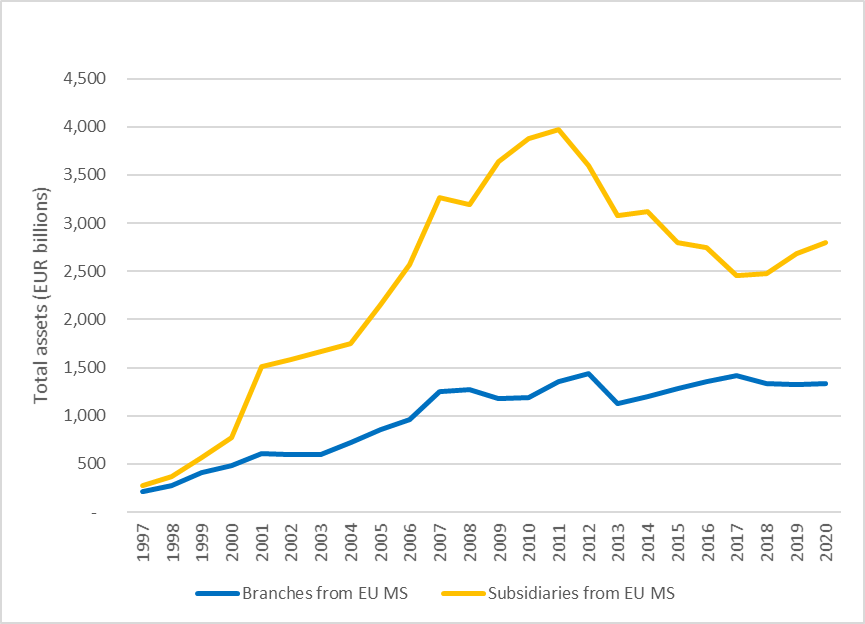

Looking back, much of the progress in cross-border integration that we saw following the creation of Economic and Monetary Union was reversed in the aftermath of the great financial crisis. And the cross-border integration of the sector has progressed at snail’s pace in recent years, even after European banking supervision was established in 2014 (see Chart 1). In fact, the measures adopted by national governments in response to the great financial crisis also led to the “repatriation” of many assets that were previously held in local subsidiaries of cross-border groups. The launch of the SSM has not yet reversed this trend. On the whole, subsidiaries currently account for around two-thirds of EU foreign assets in the euro area, while branches make up the remaining third.

Chart 1

Total EU cross-border assets in the euro area

Source: ECB structural financial indicators.

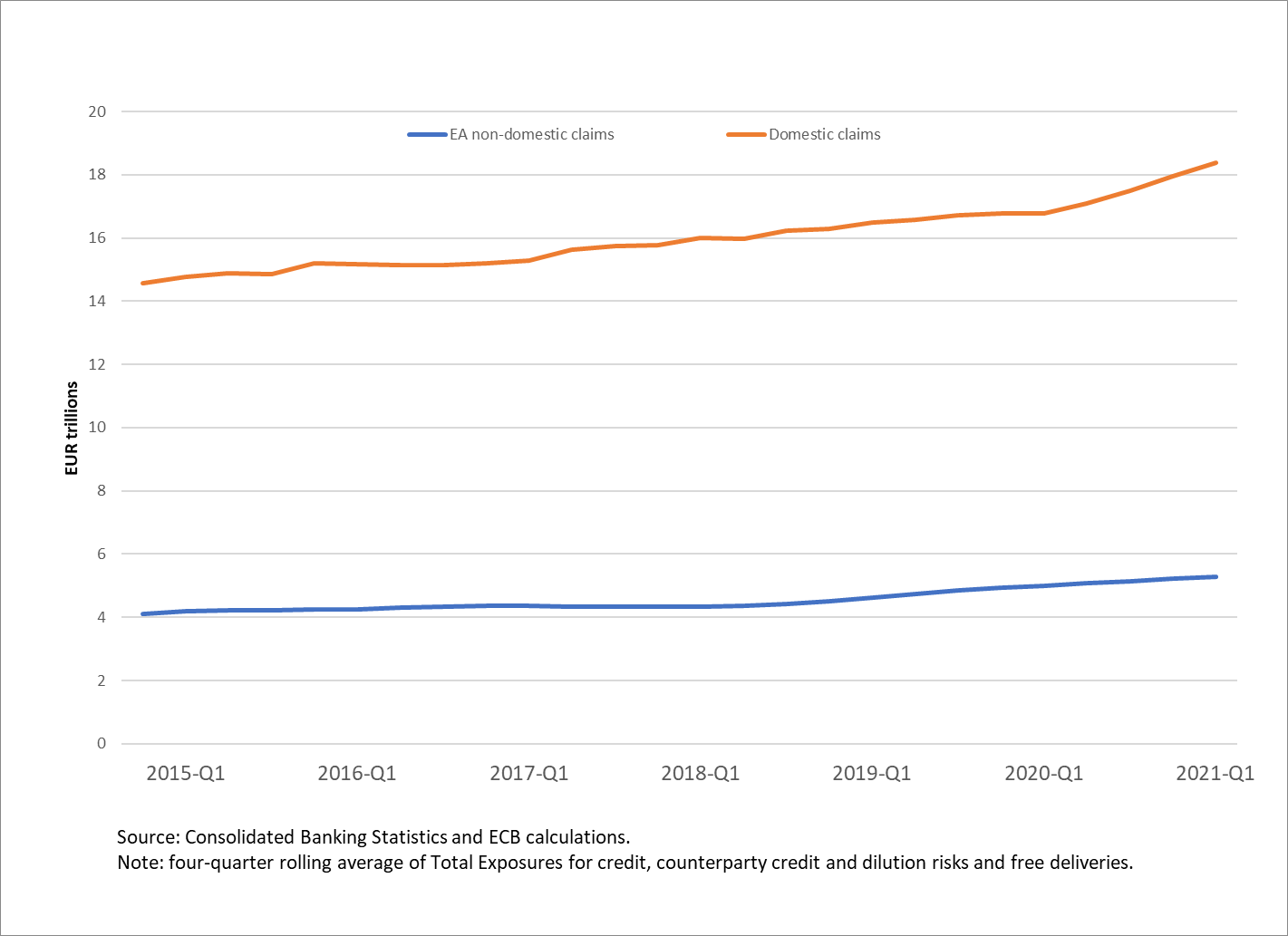

When we look at the split between foreign assets and domestic assets held by euro area banks in the years since European banking supervision was established (see Chart 2), there really does not seem to be any significant change in trend. As we also saw from Chart 1, “foreign” assets[4] in euro area banks have not changed significantly since the creation of the banking union. Banking sector integration in the euro area is still an elusive target.

Chart 2

Domestic and non-domestic claims in the euro area

And we all know why this is so detrimental. It is not only the aspect, though absolutely crucial, of denying economies of scope and scale to European banks that need to compete globally with banks that have a much deeper and more efficient domestic market, as, for instance, US banks do.

But the current limited availability of ex ante private mechanisms of risk-sharing, which integrated financial and banking markets would provide, is of the utmost concern to policymakers. Without such mechanisms, it becomes much more difficult to smooth the asymmetric shocks hitting the single monetary area. The burden falls entirely on ex post public mechanisms of risk-sharing, which reignites contentious political debates.

Former ECB President Mario Draghi convincingly argued that the mechanism of insuring against asymmetric shocks in a common currency area through financial markets “plays a key role in stabilising local economies in a monetary union, in two ways”. The first is through financial market integration, which enables firms and individuals to withstand local shocks without sudden contractions of consumption and investment, by holding geographically diversified portfolios of financial assets. It is, of course, also worth mentioning the fundamental importance of the capital markets union in this context. The second is through retail banking integration, as banks with geographically diversified portfolios can offset losses in one region with gains in another. These banks can then continue to provide credit to sound borrowers in the event of a local recession, rather than cutting lending to all customers.[5]

If we listen to those who argue that there cannot be real banking integration without ex post public risk-sharing mechanisms, such as a common deposit guarantee scheme for the euro area, we will get nowhere fast. We will not see indispensable ex ante private mechanisms of risk-sharing until ex post public mechanisms are in place. But the lack of ex ante mechanisms puts too much pressure on the functioning of public mechanisms, making their introduction even more difficult and unlikely. These vicious circles are hindering progress towards completion of the banking union.

That is why we cannot stand still. We need to move forward and make the most of the opportunities that are already available in the current European legislative framework. We need to start from somewhere and I would argue that market players can play a fundamental role here.

In the remainder of my speech, I will outline the main prudential obstacles to banking sector integration that are still embedded in the European legislative framework. I would then like to propose some potential ways of making progress within the current legislative and institutional framework, based on our ongoing discussions in ECB Banking Supervision.

The obstacles to cross-border integration embedded in the European regulatory framework

There are already several excellent analyses of the many shortcomings of the European regulatory framework[6], so today I will focus on the main obstacles to cross-border integration at the legislative level.

The Basel international standards have traditionally been based on the consolidated regulation and supervision of internationally active banks.[7] The Basel standards also introduced a framework for cooperation between home and host authorities, which is key to determining how capital and liquidity should be distributed across the different entities of a banking group. In general, locally incorporated subsidiaries of international banks are requested to fully comply with the local minimum regulatory requirements at individual entity level. For branches, national authorities often rely on the prudential requirements set by the home authorities.

When the internationally agreed standards were transposed into the European legal framework, prudential requirements in Europe were principally applied at the individual entity level, as well as at the consolidated level. By default, each and every legal entity providing banking products and services needs to fulfil prudential requirements at the solo level.

Intragroup waivers play a key role here. EU banking legislation gives supervisors the option of waiving certain prudential requirements at the level of individual banks and allowing banking groups to meet those requirements on a group-wide or sub-group basis only. Such waivers would in theory make it more attractive for banking groups to reach across borders, as they would make it possible to transfer capital and liquidity resources between legal entities in the same banking group.

But for solo capital, large exposure and leverage requirements, those waivers can only be granted for subsidiaries in the same Member State, and not in a cross-border context, even within the banking union. A similar approach was adopted for the waivers for minimum requirements for own funds and eligible liabilities under the revised Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive, the BRRD2.

The situation is better for liquidity requirements: the legislative framework does allow cross-border waivers of individual liquidity requirements, creating cross-border liquidity sub-groups. But some Member States, exercising an option that will remain in the legislation until 2028, have imposed limits on intragroup exemptions from the large exposure requirements which, as we have seen, cannot be waived, cross-border, at the solo level. This, in turn, limits the extent to which cross-border liquidity waivers can be used in practice, thereby restricting banks’ freedom to move liquidity within their groups.

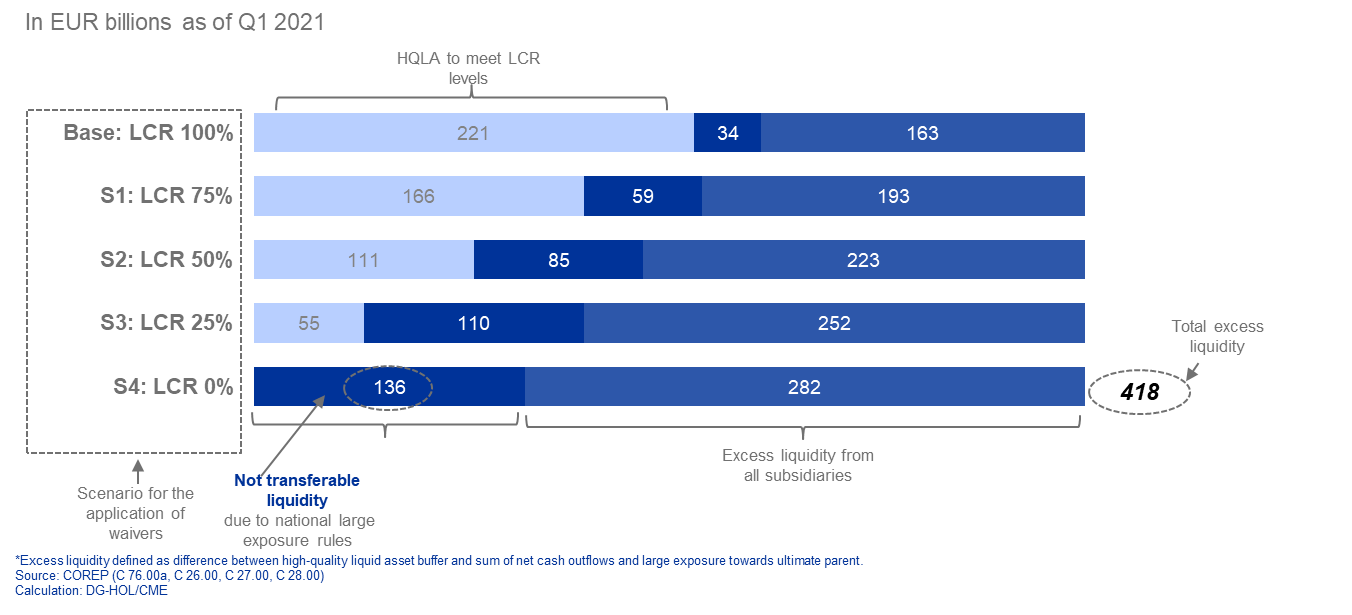

Calculations by ECB Banking Supervision show that, in the absence of cross-border liquidity waivers – as is currently the case – the combination of these European and national provisions prevents around €250 billion of high-quality liquid assets from being moved freely within the banking union.

But even if a “complete” liquidity waiver (100% of the individual requirement) were to be granted, around €140 billion of high-quality liquid assets would still not be transferable at the system level (see Chart 3).

We call those non-transferable liquid assets “trapped” liquidity, which compounds the “trapped” capital created when cross-border capital waivers are not possible. As far as capital is concerned, ECB Banking Supervision’s calculations show that the overall amount of risk-weighted assets resulting from the individual non-waivable requirements of cross-border subsidiaries in the banking union is around 25% larger than the amount of consolidated risk-weighted assets attributable to those subsidiaries at the consolidated level.

Chart 3

Excess liquidity held in the euro area by non-domestic subsidiaries of SSM significant institutions

To complete the picture, we also need to consider macroprudential requirements, for which the European legislative framework contains all the hallmarks of minimum harmonisation. In fact, most of the macroprudential requirements are enshrined in the Capital Requirements Directive, while the most relevant macroprudential provisions in the Capital Requirements Regulation relate to options for Member States. In particular, since the CRD V was enacted, it has been made clear that Member States should be free to implement other “measures in national law designed to enhance the resilience of the financial system”[8] over and above the provisions of EU legislation.

At ECB Banking Supervision, we saw this issue in sharp relief when, during the pandemic, we implemented our recommendation on dividend distribution restrictions.[9] The recommendation specified that it applied only at the consolidated level, given that our supervisory concern was one of preventing capital resources from leaving the banking system in times of extreme uncertainty. Transferring resources from one group entity to another was not – and, I would say, could not be – in our supervisory scope, especially within European banking supervision. But several Member States stopped subsidiaries within cross-border banking groups from paying dividends to their parent entity in line with macroprudential national measures that had been taken to make the national financial system more resilient. In some cases, this led to situations where the restrictions were applied to subsidiaries of foreign banks which already had solvency buffers far higher than the regulatory requirements and any reasonable solvency projections.

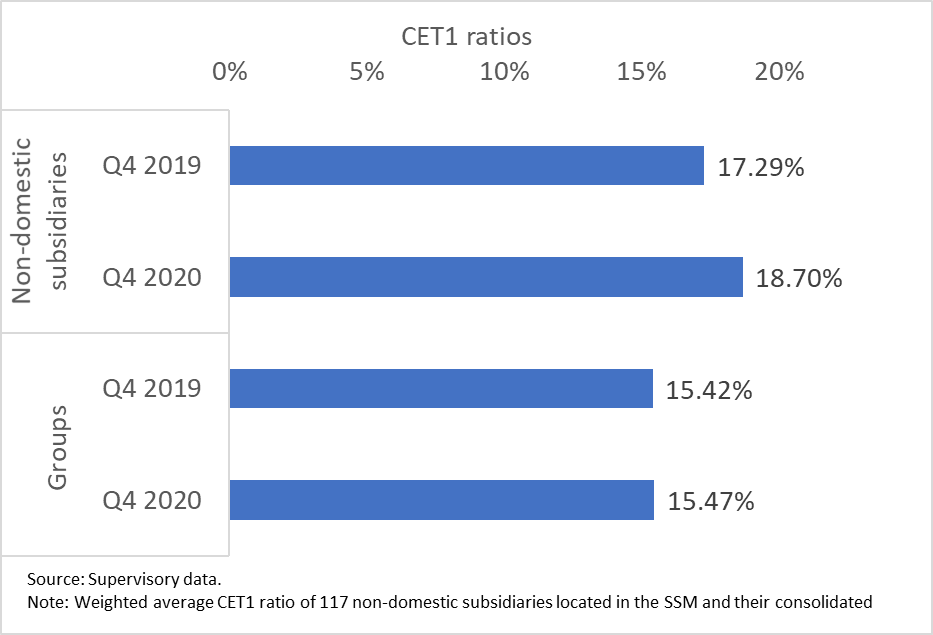

Also as a result of the application of those national measures on dividend distribution restrictions, the amount of capital held in national jurisdictions increased even further above the prudential requirements applicable to individual subsidiaries (see Chart 4).

Chart 4

CET1 ratios of parent entities and cross-border subsidiaries

The legal framework for macroprudential tools introduced after the great financial crisis entrusted national designated authorities with flexibility so they could cater to local financial and economic conditions and adjust their policies in the light of experience. Within the euro area, a safety valve was left for the ECB to intervene and top-up national measures. But the ECB can only intervene in the case of EU harmonised measures, and many national macroprudential powers are delinked from EU legislation. I would argue that, with the experience gained with macroprudential policies over the last decade, it is now time to move to a more harmonised European framework, with a stronger coordination role at the European level. This should enable the side effects of decentralised macroprudential policies to be mitigated, preventing further regulatory fragmentation along national lines. But until now there have not been specific proposals for major reforms of the macroprudential framework.

On a more optimistic note, let me end this quick survey of applicable prudential requirements with a positive development related to designated or competent authorities being able to consider the euro area as a single jurisdiction within the global systemically important institutions (G-SIIs) methodology[10].

In short, there are numerous legal prudential obstacles to the free circulation of capital and liquidity within banking groups in the euro area. While legislative reforms aimed at removing these obstacles are clearly possible, we are unlikely to see them finalised in the near future, and surely not before a fully fledged EDIS is put in place. If we want to achieve progress now, we need to pursue other avenues, which also require commitment and creative solutions from the banking industry.

Avenues to accelerate progress in the integration of the euro area banking sector

One possible avenue is to continue relying on groups that focus mainly on subsidiaries to expand their business across the banking union. A contractual approach could be developed through intragroup guarantees, which could be made enforceable, and therefore credible, using supervisory tools at the European level.

This is the proposal I developed in a blog post written with my colleague on the Supervisory Board, Edouard Fernandez-Bollo.[11] Authorities in the host Member States may be concerned that, in the event of a crisis, the parent entity might refuse to support local subsidiaries. To allay these concerns, within the banking union group support agreements for subsidiaries could be enshrined in groups’ recovery plans and approved by the supervisory authority – the ECB – which would be neutral, pursuing neither a home nor a host agenda. This could facilitate the granting of cross-border liquidity waivers at the solo level to the extent possible within the current legislative framework. Admittedly, this approach would not be an immediate game changer, as the benefits would be constrained by the limits set in the regulatory framework, but it could enable some additional pooling of liquid assets at the group level. And, most importantly, a positive experience with intragroup agreements would foster a more positive attitude at national authorities, creating the conditions for legislative change to happen sooner.

Another avenue that is more radical and challenging, but potentially more promising, would be for banks to review their cross-border organisational structure more actively, while keeping in mind the aim of banking sector integration. I am referring in particular to the possibility of relying more extensively on branches and the free provision of services, rather than subsidiaries, to develop cross-border business within the banking union and the Single Market.

I must stress that ECB Banking Supervision does not favour a specific organisational structure for cross-border banking groups under its direct supervision. These groups are completely free to choose the organisational structure that best suits their business needs, be it through branches or separate legal entities. In fact, I believe that, on a practical level, acquiring a local entity that becomes a subsidiary of the larger banking group may make it much easier to initially enter a new market. It is clearly a matter of using the local expertise and knowledge of the market, not to mention the issue of brand recognition among local customers, especially for retail business.

This notwithstanding, I am puzzled as to why banks have made little use of the basic freedoms of establishment and remote provision of services that were made available with the creation of the Internal Market back in 1992, when the Second Banking Coordination Directive[12] was transposed into national law across the then 15 Member States.

1992 is one of those totemic years in the European integration process that marks the end, or maybe the end of the beginning, of the project started with the Commission’s 1985 White Paper on completing the Internal Market[13] and the Single European Act of 1986. It is difficult to overstate the importance of those documents and decisions, including the very first Treaty amendment, for the history of European integration. But the seeds of those milestones had been sown a few years earlier by a seminal judgment of the European Court of Justice in the Cassis de Dijon case of 1979.[14] This judgment established the principle that goods and services[15] “lawfully produced and marketed in one of the Member States” must be granted free access in all the other Member States without requiring other and different requirements over and above those already imposed by the home Member State for the production of those goods and the provision of those services. On this basis, it was possible to establish a truly single, internal market in the European Union, “an area without internal frontiers in which the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital is ensured”, as enshrined in the European Treaty after the Single European Act.[16]

We are all aware of the inherent limitations of negative integration, even with the adoption of the principle of mutual recognition of national standards. But I can see a parallel between the situation back in 1979 and the situation the banking sector is in today. Back then, a fundamental judicial development helped usher in the most dramatic acceleration in the establishment of the Internal Market. And today, I would suggest that a market-based approach to banking sector integration would equally put pressure on political decision-makers, hopefully ushering in the completion of the banking union.

As I said, European banks have made little use of the freedoms that have been available to them since 1992. Branches have seldom been used to enter another country within the Internal Market, and existing subsidiaries have generally not been transformed into branches. Rather, banks have preferred to acquire local credit institutions and integrate them into a cross-border banking group. This has inevitably led to them retaining all the trappings of a separate legal entity: a separate board and support staff, local capital and local resources, separate annual accounts and treasury/finance functions and, of course, a strict application of all the local regulatory requirements on an individual entity basis. But the legal prudential framework still does not facilitate the integration of a credit institution established as a separate legal entity in another Member State. Even the establishment of European banking supervision has not yet changed this. In terms of assets, cross-border branches within the euro area still only represent a minority of intra-EU claims (see Chart 1).

All this being said, in the last few years there have been some signs of change, with a few cases of corporate integration within cross-border banking groups. Again, those were free business decisions in which ECB Banking Supervision did not play any role. The basic assumption is that banks made these choices to become more efficient. We merely granted the supervisory permissions necessary to complete the reorganisation, and there was little change in our ongoing supervision – the composition of our Joint Supervisory Teams did not change and national competent authorities continued to be represented.

The first case I would like to mention is the cross-border reorganisation of Nordea. It converted into a credit institution incorporated in Finland after transforming various separate legal entities in different European Economic Area countries (Norway, Finland and Denmark) into branches of a Swedish credit institution, which eventually became a branch of the new Finnish entity. This was a complex process that, from a legal perspective, exploited the opportunities for corporate reorganisations and mobility enshrined in the Cross-border Merger Directive[17], coupled with the freedom of establishment under the European Treaty.

A second related case concerns a Baltic cross-border group, Luminor, which was operating through a holding company and three separate banking subsidiaries in the three Baltic countries. Again, using the opportunities provided by the Cross-border Merger Directive, the two legal entities in Lithuania and Latvia were merged into the Estonian credit institution and are now operating as its branches.

And more broadly in the context of Brexit, there are numerous cases concerning third country groups, in particular Swiss and US groups, which are relocating various activities to the euro area. UBS is a good example, but many US investment banks have also taken the same approach of using the legal tool of the European Company, or Societas Europaea[18], to transform several legal entities in various Member States into branches of a credit institution incorporated in a single Member State (e.g. Germany for UBS and some US banks).

Despite the complexities of such large reorganisations, all the credit institutions contacted reported significant efficiency gains in terms of simplified legal structures and corporate governance, savings related to annual accounts and internal audit and lower overall regulatory requirements, among many others. Certainly, all the legislative prudential obstacles I have mentioned would disappear if, instead of there being separate legal entities in different Member States, capital and liquidity could flow freely within the cross-border group since a branch is structurally part of a single corporate entity.

I am not trying to paint an overly rosy picture by suggesting that those reorganisations did not entail significant costs and execution risks, for example related to IT integration. But our discussions with senior executives of the banking groups involved suggest that these costs and risks are worth it.

The final prize is a truly integrated credit institution, with a unified legal and business structure across different Member States and a return on investment over time that is clearly positive. I found it interesting that the management of one of the banks involved in these reorganisation processes described it as achieving a “one bank” operating model across multiple Member States. Of course, there will always be obstacles to a completely seamless organisational structure across national borders, such as tax rules or legislative provisions for contracts, particularly when it comes to consumer protection laws, which are especially relevant for retail banks. But this is outside the remit of prudential regulatory and supervisory authorities and there will unfortunately always be diversity in such rules across Europe. It is also worth noting that the development of the free provision of services, which should be facilitated by the increasing digitalisation of banking services, can also contribute to a simplified structure, at least for some segments of the market.

One issue that has often been raised in conversations with bank executives is a specific impediment in European banking legislation that particularly affects credit institutions with a large deposit base. I am referring to Article 14(3) of the Deposit Guarantee Schemes Directive[19], which only allows contributions made in the preceding 12 months to be transferred to a new deposit guarantee scheme (DGS). In fact, all contributions made before that period would be lost when the deposits of a credit institution leave a specific DGS to join another one, for example when a subsidiary is transformed into a branch of a credit institution established in another Member State. This provision seems counter-intuitive, at least from an economic point of view, because the transfer of insured deposits also reduces the overall risk of reimbursement of the original DGS.

ECB Banking Supervision is in favour of a legislative change along the lines already proposed by the European Banking Authority (EBA) in 2019[20], where a regulatory technical standard drafted by the EBA will specify the methodology for calculating the contributions to be transferred, without the strict limitations of the current legislative framework. One potential approach would be to allow the transfer of previous contributions net of the relative share of pay-out events, if any, that occurred during membership of the DGS. But I do not want to pre-empt the technical discussions that need to take place in order to design the most appropriate calculation methodology for the transferable contributions. What seems to be clear is that a legislative change is necessary to incentivise cross-border reorganisations of the type I have described. And, as I said, changing the provision would also make it more aligned with the underlying economic rationale because, in the case of operations through a branch, the deposits are insured by the home country’s DGS and not by the host country’s DGS.

I know that I have repeatedly said that our analysis would respect a legibus sic stantibus condition, but it is really the only legislative change we are actually looking for. It would also be consistent with the establishment of an integrated European network of national DGSs, as an intermediate step towards a fully fledged EDIS.

Conclusion

Ladies and gentlemen,

Today I have discussed some of the fundamental issues related to establishing a truly single prudential jurisdiction in the euro area, and a genuinely integrated domestic market for our banks. In the history of our Union there have been times when policymakers have driven change and supported leaps forward in European integration. But there have also been times when the private sector has seen business opportunities and structured their operations in ways that foster European integration, and by doing so they have created the conditions for a faster adjustment in the institutional and regulatory framework. I am convinced that serious initiatives taken by banking groups – under the scrutiny of their European supervisor and with the supervisor’s support – could be effective in driving positive change while waiting for major institutional overhauls.

I know that a truly integrated banking sector within the banking union is something many of you are looking forward to. But it is important to be aware that progress is in our hands – in your hands. The fundamental Treaty freedoms of movement and establishment are also there for the banking sector. Why they have been so seldom used in the past, especially in comparison with other sectors, is still open to debate. But it is never too late to start using them. As I said, in the past few years we have seen some significant corporate transformations and reorganisations that have provided noteworthy efficiency and regulatory gains for the credit institutions involved.

Within our mandate, we are ready to facilitate sound corporate reorganisations that use the opportunities embedded in the European Regulation on the Societas Europaea and the Cross-border Merger Directive. This would allow us to overcome the strictures of the current legislative framework for prudential requirements. Other pragmatic solutions, centred on intragroup agreements approved and overseen by the ECB, could also be explored for banking groups that prefer not to make use of those fundamental Treaty freedoms and decide to retain their subsidiary structure.

I would like to encourage banks interested in exploring these avenues to liaise with the ECB at an early stage to discuss possible options.

I really think that we all share the same goal here: bringing to life the vision of the European founding fathers – that of a truly internal market, also for the banking sector. At the same time, we should guarantee the stability of our Economic and Monetary Union by establishing ex ante private mechanisms of risk sharing that only an integrated banking sector can provide.

It is a daunting task. But if we do not try, we will never get there. A bottom-up market approach seems to be full of promise, and ECB Banking Supervision is ready to accompany and facilitate this process.

Thank you very much for your attention.

- The President of the Eurogroup stated: “We've made progress. We need to make more progress. We will agree a work plan, but it will take a bit more time and we will be returning to this later in the year”. See Council of the European Union (2021), “Remarks by Paschal Donohoe following the Eurogroup meeting of 17 June 2021”. In December 2020 the Euro Summit mandated the Eurogroup “to prepare, on a consensual basis, a stepwise and time-bound work plan on all outstanding elements needed to complete the Banking Union”. See Council of the European Union (2020), “Statement of the Euro Summit in inclusive format”.

- Enria, A. (2020), “The road towards a truly European single market”, speech at the 5th SSM & EBF Boardroom Dialogue, Frankfurt am Main, 30 January.

- ECB Banking Supervision (2021), Guide on the supervisory approach to consolidation in the banking sector, 12 January.

- By “foreign” assets in Chart 2 we mean exposures of euro area banks towards counterparties in other euro area countries.

- In his speech, Mario Draghi observed that “around 70% of local shocks are smoothed through financial markets in the US, with capital markets absorbing around 45% and credit markets 25%. In the euro area, by contrast, the total figure is just 25%.” The figures are based on European Commission estimates. See Draghi, M. (2018), “Risk-reducing and risk-sharing in our Monetary Union”, speech at the European University Institute, 11 May; and Nikolov, P. (2016), “Cross-border risk sharing after asymmetric shocks: evidence from the euro area and the United States”, Quarterly Report on the Euro Area, Vol. 15, No 2.

- See, for instance, Bassani, G. (2019), The Legal Framework applicable to the Single Supervisory Mechanism. Tapestry or Patchwork?, Wolters Kluwer, Alphen aan den Rjin; and Gardella, A., Rimarchi, M. and Stroppa, D. (2020), “Potential regulatory obstacles to cross-border mergers and acquisitions in the EU banking sector”, EBA Staff Paper Series, No 7, European Banking Authority, February.

- See the clear introduction to paragraph 10 of the First Basel Capital Accord: “This agreement is intended to be applied to banks on a consolidated basis, including subsidiaries undertaking banking and financial business”. Moreover, as mentioned in paragraph 1 of the Accord, the aim of the Basel Committee was to “secure international convergence of supervisory regulations governing the capital adequacy of international banks”. See Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (1988), International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards, July.

- See Recital 22 of Directive (EU) 2019/878.

- For the ECB’s first recommendation on dividend distributions in March 2020, see Recommendation of the European Central Bank of 27 March 2020 on dividend distributions during the COVID-19 pandemic and repealing Recommendation ECB/2020/1 (ECB/2020/19) (OJ C 102I , 30.3.2020, p. 1).

- See Article 131(2)(a) of the Capital Requirements Directive, as introduced by Directive (EU) 2019/878. This legislative change also led to the amendment of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 1222/2014 supplementing Directive 2013/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to regulatory technical standards for the specification of the methodology for the identification of global systemically important institutions and for the definition of subcategories of global systemically important institutions (see Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/539).

- See Enria, A. and Fernandez-Bollo, E. (2020), “Fostering the cross-border integration of banking groups in the banking union”, The Supervision Blog, 9 October.

- Second Council Directive 89/646/EEC of 15 December 1989.

- See Commission of the European Communities (1985), Completing the Internal Market, White Paper from the Commission to the European Council, 14 June.

- See Case C-120/78, delivered on 20 February 1979. The fundamental statement of that ruling is in paragraph 14: “there is….no valid reason why, provided that they have been lawfully produced and marketed in one of the Member States, alcoholic beverages should not be introduced into any other Member States.”

- For services, and in particular financial and banking services, see the Commission’s White Paper, supra footnote 13, paras. 102-104.

- See Article 26 TFEU.

- Directive (EU) 2017/1132, subsequently amended by Directive (EU) 2019/2121.

- See Council Regulation (EC) No 2157/2001.

- Directive 2014/49/EU.

- See paragraph 7.ii. of EBA (2019), “Opinion of the European Banking Authority on the eligibility of deposits, coverage level and cooperation between deposit guarantee schemes”, 8 August. See also pp. 16-25 of the report attached to the Opinion.

Bank Ċentrali Ewropew

Direttorat Ġenerali Komunikazzjoni

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, il-Ġermanja

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Ir-riproduzzjoni hija permessa sakemm jissemma s-sors.

Kuntatti għall-midja