LSI supervision report 2022

Executive summary

The macroeconomic disruptions brought about by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and major geopolitical tensions in conjunction with accumulated pressures from the sustained low interest rate environment of previous years have posed an unprecedented sequence of challenges to the financial system. This report examines key developments in the less significant institutions (LSI) sector, its structure and major activities aimed at addressing challenges from the supervisory perspective.

LSIs represent around 18% of total banking assets in Europe while the number of LSIs has declined by about 1,000 since the inception of the SSM.

As part of the shared responsibilities in LSI supervision and oversight in the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), the national competent authorities (NCAs) retain responsibility for the direct supervision of LSIs, which represent 18% (incl. FMIs) of banking assets – a share which has increased slightly since the inception of the SSM (2015: 16.7%). The ECB is responsible for authorising LSIs across the euro area and, through its LSI oversight function, ensures effective and consistent supervision in all SSM countries. Bulgaria and Croatia joined the list of SSM countries in October 2020, when the ECB entered into a close cooperation with Българска народна банка (the Bulgarian National Bank) and Hrvatska narodna banka.

Strong retail footprint for the LSI sector, with an increasing share of specialised business models.

The structure of the LSI sector in the SSM reflects a continued consolidation trend, albeit at a slower pace in 2021 than in previous years. Between the end of 2014 (inception of the SSM) and the end of 2021, the number of LSIs fell from more than 3,167 to about 2,089, with Germany, Austria and Italy accounting for the bulk of this reduction. In 2021 alone, the number reduced by about 90 entities. At the same time, the aggregate balance sheet of the LSI sector increased by 4.1% in 2021, a similar pace to significant institutions (SIs) (3.8%). This reflects a moderate growth in the loan portfolio and a significant increase in cash balances at central banks, but with major differences across countries. Generally, deposits from households represent the key funding source for LSIs at around 45% of total liabilities (including equity); however, like the structure of the loan book, the funding profile differs significantly across countries. In 2022 total assets have continued to grow strongly so far. In the second quarter of 2022 total assets rose by 2.4% compared to the end of 2021 to €4,910 billion, whereas only in a few countries assets decreased compared to the second quarter 2021.

Profitability remains weak for key businesses…

Overall, LSI profitability remains low despite a partial recovery in 2021. The average return on assets (RoA) increased from 0.17% to 0.34%, and the return on equity (RoE) showed an even more pronounced increase (from 1.8% to 3.5%). This is roughly in line with the SI sector, which started with a lower RoA (0.10%) but in 2021 achieved stronger profit levels (0.43%), while its RoE also started from a lower value compared to LSIs (1.53%) but recovered even more strongly (to 6.70%). A key driver of the profit recovery for LSIs was a significant decrease in provisioning, while net interest income (NII) continued to decline. The cost/income ratio stood at 70.2% for the LSI sector, notably worse than the corresponding figure for SIs (64.3%), despite improving slightly from 71.5% at the end of 2020. For the vast majority of LSIs, profitability remains a key pain point which needs to be addressed to improve resilience. As of the second quarter of 2022 profitability weakened again in the light of macroeconomic developments on aggregate, with significant differences across countries also given the divergent impact of interest rate shifts on banks’ income.

… while loan portfolios are exposed to both legacy and new risks…

Following the early stages of the coronavirus crisis, LSI credit volumes exhibited moderate growth, while non-performing loan (NPL) ratios continued to fall gradually. LSIs’ aggregate NPL ratio[1] at SSM level showed a steady downward trend to 1.8% at the end of 2021 (2018: 2.2%) despite the pandemic. This was fairly consistent at country level, showing that, broadly, risks from the pandemic did not materialise to the extent expected at the outset, thanks to public support measures in particular. The war in Ukraine and the worsened macroeconomic situation have given rise to new concerns since early 2022, however, despite early impact analysis suggesting direct exposures to Russia are manageable for SSM banks in aggregate, with some individual exceptions. Supervisors have also been focusing on risks stemming from indirect effects with a more medium-term horizon, such as exposures to vulnerable sectors. These second-round impacts could have far wider implications, given the macroeconomic outlook. Supervisors have also intensified their monitoring of potential losses stemming from disruption in financial markets and cyber risk activities.

… posing potential risks to capital positions, although these remain comfortable for the time being.

Asset growth, paired with low profits, caused LSIs’ total capital ratio to decline by 0.51 percentage points to 18.81% in 2021. While this is below the average total capital ratio for SIs of 19.57%, it remains relatively comfortable and the share of high-quality capital – reflected in the CET1 ratio – is higher than for SIs (17.32% vs. 15.58%). The average risk-weighted asset density is higher for LSIs (49.7%) than for SIs (33.4%). In total, there were 13 breaches of overall capital requirements at the end of 2021 in the LSI sector. The leverage ratio (fully phased-in) increased by 0.71 percentage points to 9.1% and remains well above the 3% requirement on aggregate. As of second quarter in 2022, capital levels were further declining in nearly all countries.

The immediate liquidity risk seems limited, but LSIs remain vulnerable to sudden shifts.

LSIs’ liquidity position benefited from a significant increase in deposits, especially those coming from non-financial corporations, as well as increases in central bank funding. As part of the ECB’s targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), a total of €224 billion has been allocated to a total of 769 LSIs. Some idiosyncratic risks may remain, not only with regard to replacing central bank funding but also in the light of the increasing costs of wholesale and deposit funding. The liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) declined from 221% to 201% in 2021.

Supervisory assessments in 2021 focused on key aspects of credit risk, business models and internal governance.

In view of these risks, a number of SSM-wide initiatives were carried out in cooperation between the ECB and NCAs in 2021. Credit risk naturally constituted a major focus area, with SSM activities looking at improving benchmarking across the euro area. Particular attention was paid to aspects such as classification and provisioning and promoting best practices in various aspects of NCAs’ supervisory approaches, ranging from stress testing to targeted on-site inspections. The focus has now shifted to the potential impact of the Russia-Ukraine war and ECB Banking Supervision has set up a contact group across national supervisors to coordinate analysis and responses. Rapid balance sheet growth at individual LSIs was subject to systematic analysis as well. Governance arrangements of LSIs were examined in a thematic review; the findings on matters such as board composition and functioning call for further improvements.

Other activities focused on third-country exposures, online deposit platforms and IPS monitoring.

Other relevant initiatives worth mentioning include:

- targeted analysis of third-country exposures due to Brexit (as also done for SIs) and to non-EEA emerging economies;

- an assessment of the relevance of online deposit platforms, which are now being used by almost 100 LSIs across 16 jurisdictions;

- work on institutional protection schemes (IPSs) via continued annual monitoring in the light of past findings aimed at strengthening the reliability of hybrid IPSs;

- analysis of the NCAs’ identification of financial holding companies (FHCs) in the LSI sphere, which has resulted in numerous case-specific findings and brought several aspects of policy relevance to the surface which are being followed up in the relevant SSM fora;

- onboarding of NCAs to a common SSM web-based platform (IMAS) for conducting and documenting LSI risk assessments;

- further harmonisation of Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) methodology in relation to LSIs.

The NCAs, the direct supervisors of LSIs, also performed a number of relevant activities. The key supervisory priorities for NCAs were credit risk, business model sustainability, operational resilience and governance. These were tackled by on-site inspections and thematic reviews, among other things.

The outlook for the LSI sector remains challenging; both new and existing uncertainties are hampering the adjustments needed to achieve sustainable profits.

For 2022 the key priorities for supervisory activities remained credit risk, operational risk – predominantly with regard to cyber security and operational resilience – and governance. Key activities in 2022 included following up on the thematic review of governance and further quantitative and qualitative benchmarking of supervisory activities and practices in the area of credit risk. Supervisory priorities must, however, retain the flexibility to adapt to changes in the risk landscape, for example from geopolitical tensions.

All in all, the outlook for the LSI sector remains challenging, particularly given the numerous uncertainties around second-round effects from the war in Ukraine. The consequences are difficult to foresee at this stage, so banks have to be prepared for significant volatility in financial markets and the real economy. This implies challenges related to asset pricing, increases in non-performing exposures and funding access. NCAs must take a supervisory approach that is flexible and risk-sensitive. This will be supported by oversight activities performed by the ECB.

Please note that the LSI sectors in Member States participating in the SSM vary greatly in terms of number, size of assets and business models. This has implications for the comparability of LSI country aggregates. The cut-off date for this report was 7 October 2022 for LSI data unless otherwise stated; any information received after that date may not be fully reflected. The sample of LSIs refers to banks at their highest level of consolidation excluding branches and – unless otherwise indicated – excluding financial market infrastructures (FMIs) such as central counterparties (CCPs) and central securities depositories (CSDs); the size of these usually exceeds the significance threshold even though they may not be classified as significant institutions. For information on supervisory activities, the analysis focuses only on information reported by NCAs, bearing in mind that not all dimensions of supervisory activities can be reflected, and different interpretations may apply. For more details on technical assumptions, please refer to Annex D. Confidentiality rules protecting dissemination of individual bank data are being put in place currently.

1 The SSM approach to LSI supervision

1.1 The organisation of banking supervision in the SSM

The role of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), which comprises the ECB and the national competent authorities (NCAs) of participating Member States, is to ensure that EU policy on the prudential supervision of credit institutions in the euro area is implemented in a consistent and effective manner and that credit institutions are subject to supervision of the highest quality. The SSM’s three main objectives are to:

- ensure the safety and soundness of the European banking system;

- increase financial integration and stability;

- ensure consistent supervision.

The ECB exercises oversight over the functioning of the system based on the procedures and responsibilities set out in the SSM Regulation[2] and the SSM Framework Regulation[3] and conferred upon the ECB and NCAs for significant and less significant institutions respectively. The ECB and the NCAs perform their tasks in close cooperation, taking into account their economic and organisational specificities. While the ECB is responsible for direct supervision of significant institutions (SIs) via joint teams composed of ECB and NCA experts, the NCAs retain responsibility for supervising less significant institutions (LSIs). The national supervisors plan and carry out their ongoing supervisory activities using their own resources and decision-making procedures.

However, for certain common procedures the ECB has full responsibility for all SSM credit institutions. These are carried out in cooperation with NCAs and concern the granting and withdrawal/lapsing of bank licences and the acquisition of qualifying holdings according to Article 4(1)(c) of the SSM Regulation. Under Article 4(1)(a), the ECB is exclusively competent to grant authorisations to take up the business of a credit institution. Articles 6(4) and 14 provide that this competence extends to both SIs directly supervised by the ECB and LSIs directly supervised by the NCAs. The SSM Framework Regulation elaborates on the powers of authorisation, focusing on the respective roles of the relevant NCA and the ECB in the assessment process. Under Articles 4(1)(a) and 14(5) of the SSM Regulation, the ECB also has the competence to withdraw authorisations in the cases set out in the relevant EU or national law. The ECB and the national supervisors are involved in different stages of these common procedures, but the entry point for all applications is the national supervisor of the country where the bank is/will be located, irrespective of significance status. The national supervisors and the ECB cooperate closely throughout the whole procedure, but, for all supervised credit institutions, the final decision is taken by the ECB.

1.2 Oversight of LSIs by the ECB

The ECB in its oversight function is responsible for the effective and consistent functioning of the SSM. The ECB needs to ensure that a level playing field applies to all banks in the euro area, including LSIs, while considering the different features of the national banking systems and the respective supervisory approaches. Proportionality plays an important role in this context, which is why, jointly with NCAs, the ECB has developed a classification regime for LSIs. This aims to ensure that the approach to supervising and overseeing LSIs is proportionate and commensurate to the risks that individual institutions pose. LSIs are currently classified on the basis of their impact on the financial system and their risk profile. As of 2022, impact criteria[4] and risk criteria are assessed separately. High-impact LSIs are determined once a year for each of the countries participating in European banking supervision. The classification is subject to an annual review in cooperation with NCAs to ensure that the list is suitably updated.

Box 1

The ECB classification regime for LSIs

The SSM Framework Regulation states that “the ECB shall define general criteria, in particular taking into account the risk situation and potential impact on the domestic financial system of the less significant supervised entity concerned, to determine for which less significant supervised entities which information shall be notified”. The need to have a high priority list was identified from the very beginning of the SSM in November 2014.

An LSI can be deemed “high priority” for various reasons: size, intrinsic riskiness, impact on the national economy or interconnectedness with the rest of the financial system.

In January 2021 the Supervisory Board revised the classification framework in line with the experience gained since the beginning of the SSM. The new classification methodology introduces the categories of high-impact LSIs and high-risk LSIs, which are identified using separate impact and risk criteria. This replaces the LSI prioritisation concept used before, under which combined impact and risk criteria divided institutions into high, medium and low priority. The new methodology came into effect from January 2022.

LSIs are classified as high-risk on the basis of a risk assessment by the NCA and their compliance with capital and leverage requirements. For classification as high-impact, the following criteria are used:

- Size: total assets > €15 billion;

- Importance for economy: either the institution’s ratio of total assets to GDP is at least 15% or it has been identified by the NCA as an “other systemically important institution” (O-SII);

- Cross-border activities: an institution which is the head of a group supervised by the SSM is classified as high-impact if the group consists of two or more credit institutions incorporated in two or more participating Member States;

- Potential SI: the institution is identified as a “large institution” according to the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR)[5] or an LSI under “particular circumstances” as set out in the Article 70 of the SSM Framework Regulation;

- Business model: due to their systemic relevance, institutions such as financial market infrastructures (FMIs) with a banking license, i.e. central counterparties (CCPs) and central securities depositories (CSDs), are deemed high-impact; so too are non-sector-consolidating central savings banks or central cooperative banks (CCBs) and central institutional protection scheme (IPS) institutions, due to their interconnectedness.

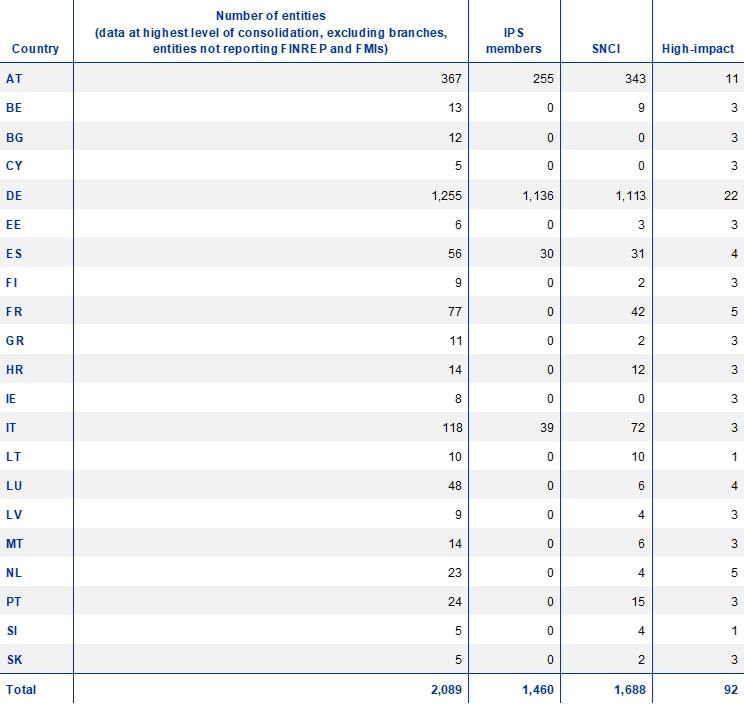

In addition, at least three LSIs per country should be classified as high-impact to ensure minimum coverage, although exceptions are possible. An LSI that is considered a small and non-complex institution (SNCI) within the meaning of the CRR cannot be designated high-impact unless it is the largest LSI in a jurisdiction where all LSIs are SNCIs.

The exercise to identify high-impact LSIs is performed annually (see Annex A) and the resultant list is published. By contrast, the update for high-risk LSIs is done more frequently (quarterly), and the outcome remains confidential for financial stability reasons.

The resulting classification has implications for effective supervision and determines which notifications NCAs have to submit to the ECB and whether this is done in advance or in arrears. The revised LSI notification guidance provides clearer criteria for NCAs to determine whether a particular development should be reported to the ECB and, if so, in what form. It will improve the risk focus of LSI supervision and enable a more targeted exchange of information between NCAs and the ECB. In the case of high-impact LSIs, a multi-year SREP approach applies. This allows the supervisor to tailor the depth of the analysis of each risk for each year. Any risk may be assessed, but the internal capital adequacy assessment process (ICAAP) and internal liquidity adequacy assessment process (ILAAP) must be performed annually. Supervisory capital stress tests for high-impact LSIs should be conducted at least every second year.

In addition, with a view to establishing a more proportionate regulatory framework, CRR II[6] established a new classification of institutions by introducing definitions of “large institution” (Article 4(146) CRR)[7] and “small and non-complex institution” (SNCI) (Article 4(145) CRR)[8]. At a consolidated level, 80% of all LSIs (1,688 institutions) qualify as SNCIs. The introduction of this new category was followed by a set of provisions applicable solely to SNCIs aimed at reducing regulatory costs for these banks. They include less frequent and less detailed disclosure and reporting requirements and a simplified, less granular calculation of the net stable funding ratio (NSFR).

The vast majority of LSIs are classified as SNCIs.

The ECB’s oversight activities related to LSIs are divided between vertical supervision, organised across country desks for all countries participating in the SSM, and horizontal activities supported by horizontal business areas responsible for policy and methodology development. Vertical supervision focuses mostly on high-impact and high-risk LSIs. As the direct supervisors of LSIs, NCAs retain full responsibility for carrying out assessments and deciding on capital, liquidity and qualitative measures.

Since 2015 the ECB and the NCAs have been working together to develop a common SREP methodology for LSIs, based on the EBA SREP Guidelines and building on the methodology for SIs and existing national SREP methodologies. The SREP for LSIs aims to promote supervisory convergence in the sector while supporting a minimum level of harmonisation and a continuum in the assessment of SIs and LSIs. NCAs may exercise a degree of flexibility when implementing LSI SREP methodology to account for national specificities. Another important milestone to ensure consistency and high supervisory standards for LSI supervision is the roll-out of the SSM information management system for NCAs (the IMAS portal)[9], which facilitates assessment on the basis of the common SREP methodology and allows supervisors of LSIs to record this assessment in a single system across the SSM.

1.3 Enlarging the LSI sector in the SSM through close cooperation with Bulgaria and Croatia

On 1 October 2020, following a comprehensive assessment of Bulgarian and Croatian credit institutions, the ECB entered into close cooperation with the Bulgarian National Bank and Hrvatska narodna banka.[10] From that date, the ECB took on responsibility for the oversight of LSIs. It was also entrusted with common procedures for all supervised entities in the two countries.

1.3.1 The process of establishing close cooperation

Bulgaria and Croatia joined under a close cooperation agreement in October 2020 and are already well integrated into the SSM.

Before the two NCAs became part of the SSM, they went jointly with the ECB through a preparatory process aimed at operationalising their future collaboration. This included developing supervisory convergence plans, specifying action points in relation to LSI supervision, such as adapting organisational structures and staffing needs and preparing for the implementation of joint supervisory practices for LSIs.

After the start of close cooperation, the process of onboarding and integrating both NCAs into the ECB’s LSI oversight function was structured around a roadmap covering technical interactions and training. The roadmap aimed to bring supervisors together by discussing, for example, the supervisory approach to particular risk elements, supervisory practices such as on-site inspections and stress testing, the SREP and the crisis management framework.

The situation has now moved to “business as usual” status, with supervisors cooperating closely to address the challenges faced by Bulgarian and Croatian LSIs. Both NCAs are benefiting from the ECB’s expert knowledge, methodologies and training, contributing to further convergence in supervisory approaches to LSIs.

1.4 The organisation of LSI supervision activities

NCAs are responsible for direct supervision of LSIs; the ECB mainly provides support through its oversight function. The ECB is also responsible for authorising common procedures for all LSIs (as well as SIs). These include acquisitions of qualifying shareholdings, banking licences (and licences for investment firms that qualify as credit institutions) and the withdrawal/lapsing of these licences, as well as decisions on the significance of banks and requests related to passporting.

To perform their LSI supervisory duties, NCAs tend to split their activities into off-site and on-site work.

On-site inspections allow a very intrusive and in-depth perspective into supervised institutions, typically focusing on specific topics or risk areas.

Off-site supervisory activities are generally broader in nature and include different types of bank-specific or horizontal assessments, meetings with management or supervisory bodies and issuance of decisions. The SSM has no predetermined minimum engagement per activity, but NCAs usually set a minimum frequency for most activities, grouping their home LSI banking sector into up to four different clusters along characteristics such as banking sector, risk classification and size. The actual frequency may differ to reflect ongoing needs and address risks in a focused manner.

Formal SREP decisions are usually issued annually by most NCAs. As the number of LSIs differs significantly from country to country, some LSIs might not receive annual SREP decisions. The related SREP assessment is generally updated in line with the decision.

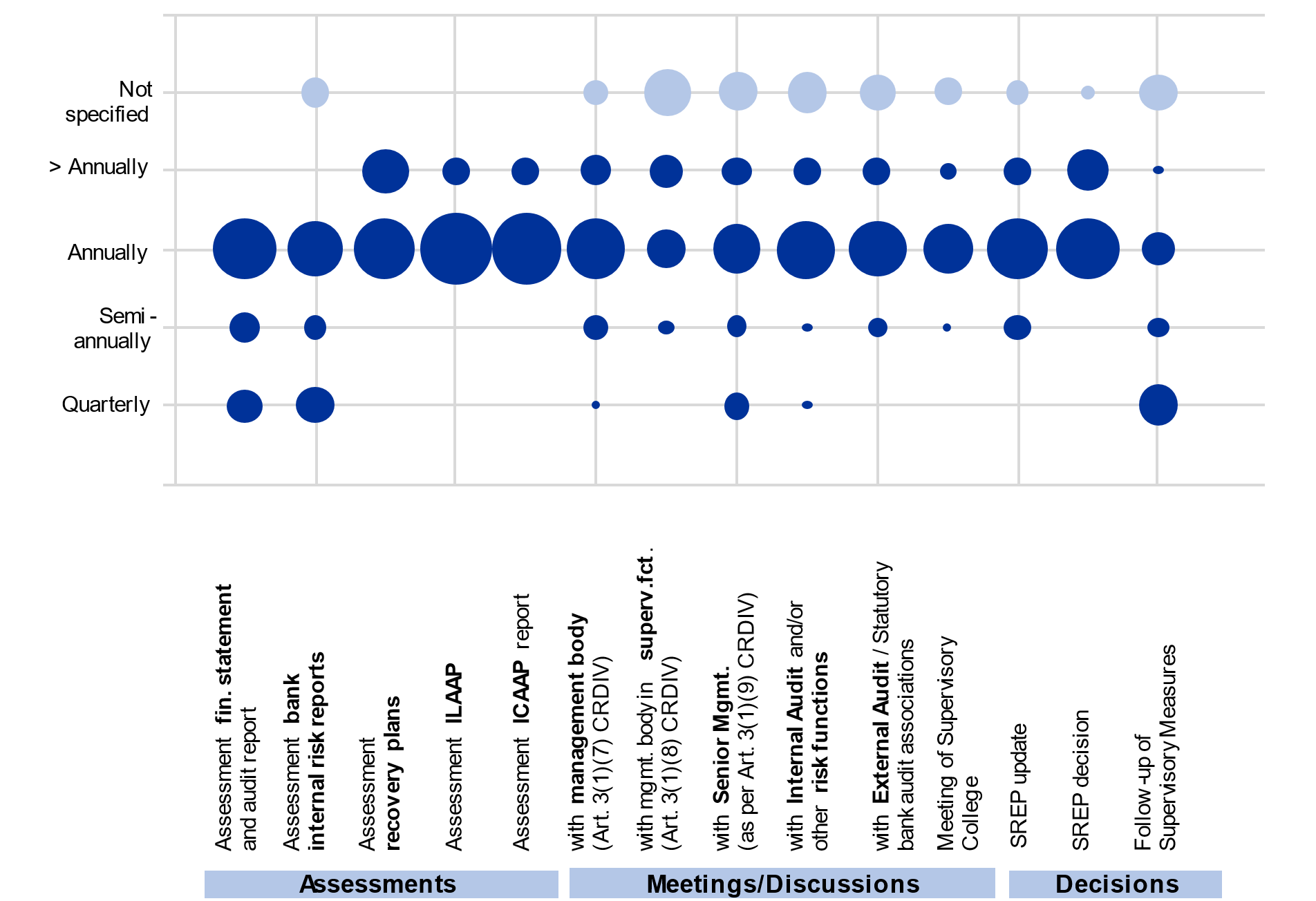

Chart 1

Frequency of key supervisory activities

(frequency)

Note: The size of the dots refers to the number of NCAs that apply the indicated frequency for any of their defined minimum engagement clusters according to their annual planning.

Meetings with institutions are an important supervisory tool but difficult to execute on a large scale in countries with high number of LSIs, even where NCAs have better staffing.

Staff resources for LSI supervision vary greatly between SSM countries and depend strongly on the characteristics of the national banking system (e.g. the number of LSIs and size of the LSI sector, the presence or absence of IPSs, special business models, crises, etc.). For some countries, staffing is often below one full-time equivalent (FTE) per LSI for both on-site and off-site staff.

2 The structure of the LSI sector

2.1 Consolidation in the LSI sector

The consolidation trend in the LSI sector continued in 2021, albeit at a slower pace than in previous years. The number of LSIs has fallen steadily since the inception of the SSM, from 3,136 at the end of 2015 to 2,089 at the end of 2021.[11]

The number of LSIs declined further to 2,089; there are now over 1,000 fewer entities than at the inception of the SSM.

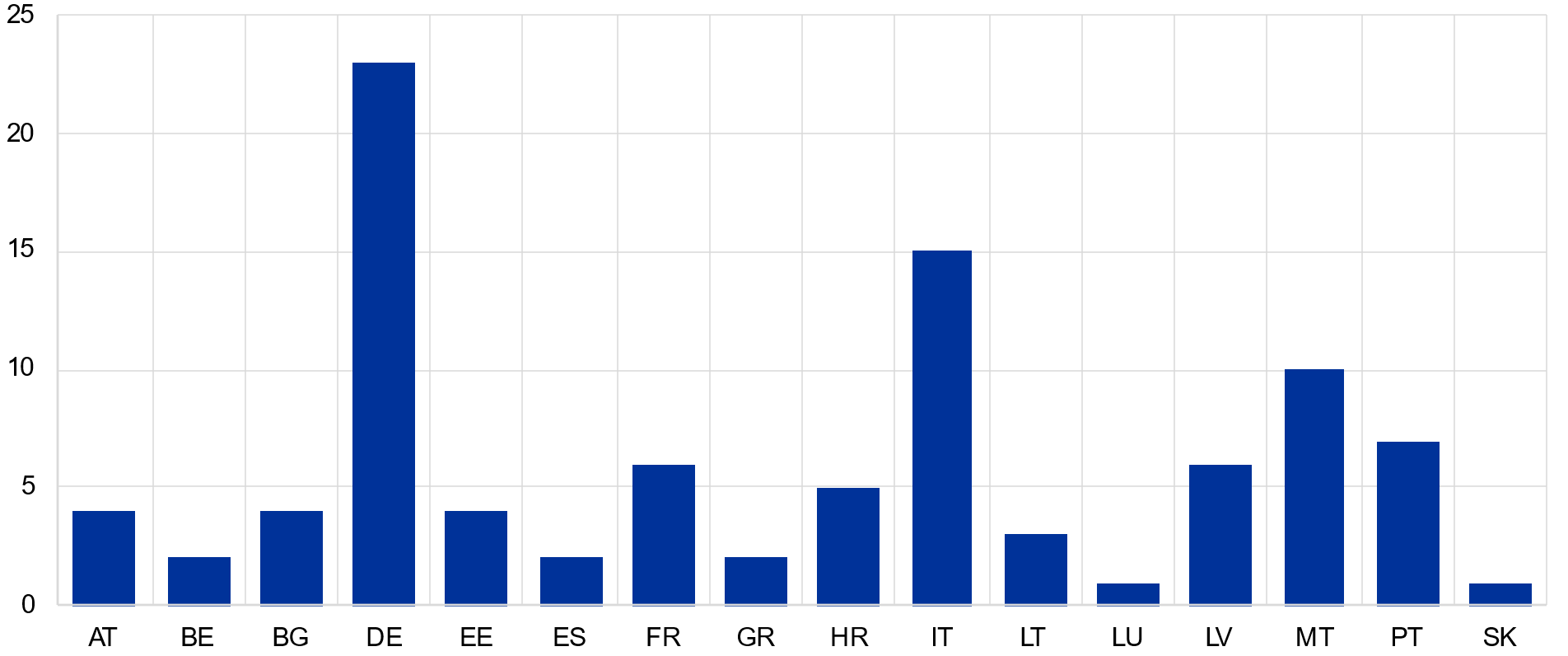

A significant contributing factor behind this was the consolidation of the cooperative banking sector in Italy into three major groups, which concluded in 2019 and saw 228 institutions consolidated into two SI groups and one LSI group. The number of mergers and acquisitions completed in 2021 confirms the trend towards consolidation observed in the LSI sector since European banking supervision started. However, the pace of consolidation slowed down last year: a total of 61 LSIs were acquired or merged, compared with 69 in 2020. Germany was the main driver of consolidation last year, reflecting the high number of LSIs in that country: 48 mergers were finalised in Germany in 2021, compared to 30 in 2020. The number of institutions whose licence was withdrawn remained almost unchanged: ten LSIs across all 21 SSM countries in 2021, compared to nine in 2020.

Withdrawals were related mainly to voluntary terminations of business activity and mergers or other types of restructuring. In 2021, four LSIs exited the market as a result of involuntary liquidation procedures, including insolvency proceedings, and there were 32 cases of licences lapsing.[12] This was only partially offset by the six new LSI licences granted in five jurisdictions in 2021 and the ten new entities (branches or FHCs) that were established within the SSM. As in previous years, the main driver of new applications was the increased use of digital innovation to provide services to EU clients (i.e. fintech business models).

As a result of the annual assessment of significance, three institutions were added to the list of significant supervised entities: Banca Mediolanum S.p.A. and Finecobank S.p.A. in Italy and Danske Bank A/S, Finland branch, were classified as significant because their assets exceed €30 billion. Only one institution (Dexia Bank of France) was reclassified from SI to LSI. Following the addition of Bulgaria and Croatia to the LSI landscape, 26 new LSIs (14 Croatian and 12 Bulgarian) now fall under the indirect supervision of the ECB.

Despite the fact that the consolidation trend has been most prominent in Germany, Austria and Italy and the number of LSIs has declined significantly in recent years, these three countries continue to make up the bulk of the sector. At the end of 2021, over 83% of all LSIs were domiciled in Germany, Austria and Italy, reflecting their large decentralised systems of savings and/or cooperative banks, which are often covered under a joint IPS. About two-thirds of the LSIs operating in countries under European banking supervision are members of an IPS (1,421 banks at the end of 2021), the majority belonging to one of the two German IPSs (which cover a total of 1,136 institutions). Cooperative and savings banks typically operate as traditional banks, while also providing financing to the local community or cooperative members. They are a feature of many countries, but their organisation and corporate structure differ. For example, in France the cooperative banks have consolidated into significant groups and do not count as LSIs. In Finland, although the number of individual LSIs is high, most are cooperative and savings banks belonging to the two amalgamations of deposit institutions.[13]

2.2 Market share of LSI sectors

The market share of LSIs has slightly increased since inception of the SSM despite the decline in the number of LSIs, confirming the ongoing consolidation.

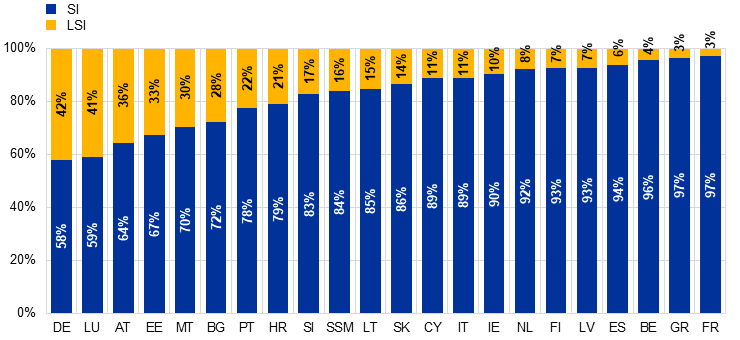

The continuous growth in average LSI assets has resulted in a stable share of 18%[14] of total banking assets in the euro area, a slight increase compared with 2015 (16.7%). However, the weight of the LSI sector varies widely across SSM countries. While LSIs represent around 40% of total banking assets in Luxembourg and Germany, their importance is substantially lower in other countries, notably in Greece (3.5%) and France (2.9%), where the banking systems are dominated by domestic SIs. Relative to the size of the domestic economy, the biggest LSI sector can be found in Luxembourg, where LSIs primarily focus on private banking and custodian banking and have accumulated assets representing 193.7% of GDP. The next two largest LSI sectors as a percentage of GDP are in Austria (89.9%) and Germany (83.6%).

Chart 2

Market share of SIs and LSIs by country

(percentages of total assets)

Source: ECB calculations based on FINREP F 01.01, F 01.01_DP.

Notes: The chart generally displays the market share calculated at the highest level of consolidation in the SSM. This means that branches and entities that are subsidiaries of SSM parent entities are included in the total assets of their parent entities and are not considered in the respective market share of the local banking sector. For BG, HR and SK exceptions to this general methodology are made and the market shares of SIs in these countries include the total assets of entities that are local subsidiaries of cross-border SSM parent entities. The market share percentages for BG, HR and SK therefore follow a different methodology and are not directly comparable to those of the other countries on the chart.

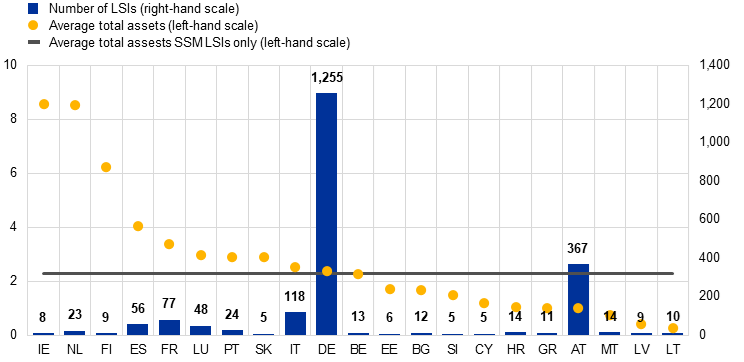

In 2021, the average size of an LSI was €2.3 billion, compared to the average size of an SI of €222.1 billion (median: €819.4 million). Irish LSIs (€8.6 billion) have the largest average size, followed by the Netherlands (€8.5 billion), and Finland (€6.2 billion), while the smallest average sizes are in Lithuania (€0.3 billion) and Latvia (€0.4 billion). For the LSI sectors in countries that recently joined the SSM through close cooperation, the assets of Croatian LSIs amount to €14.5 billion in total and those in Bulgaria amount to €19.8 billion. These figures represent 0.30% and 0.41% of the SSM LSI sector respectively.

Chart 3

Number of LSIs and average size in 2021

(left-hand scale: total assets, EUR billions; right-hand scale: number of LSIs)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities (excl. FMIs), FINREP F_01.01, F_01.01_dp.

Note: Number of SSM LSIs (excluding branches) at the highest level of consolidation (excl. FMIs).

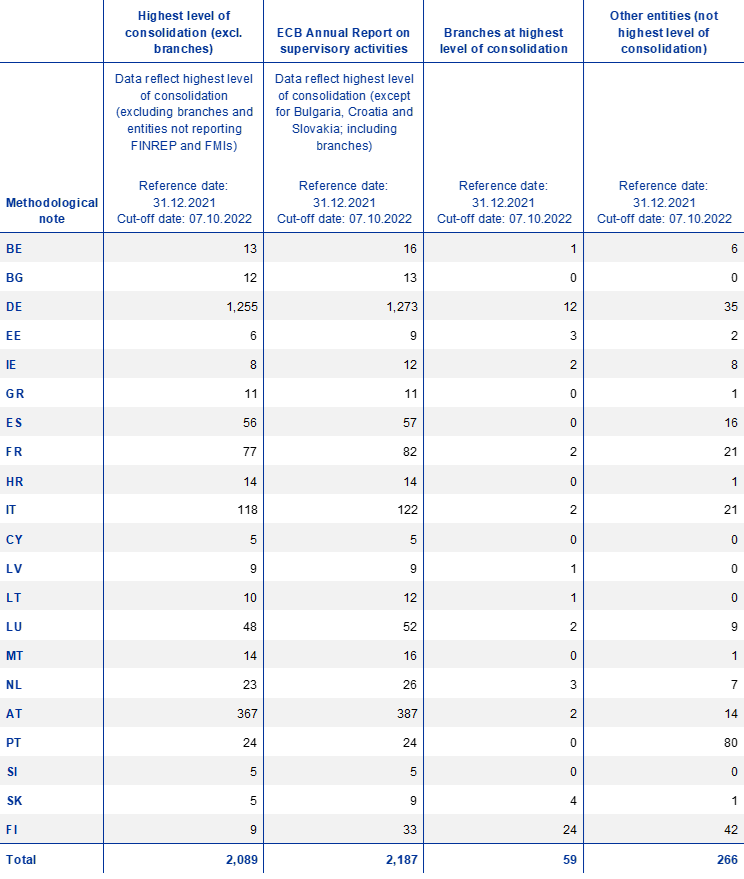

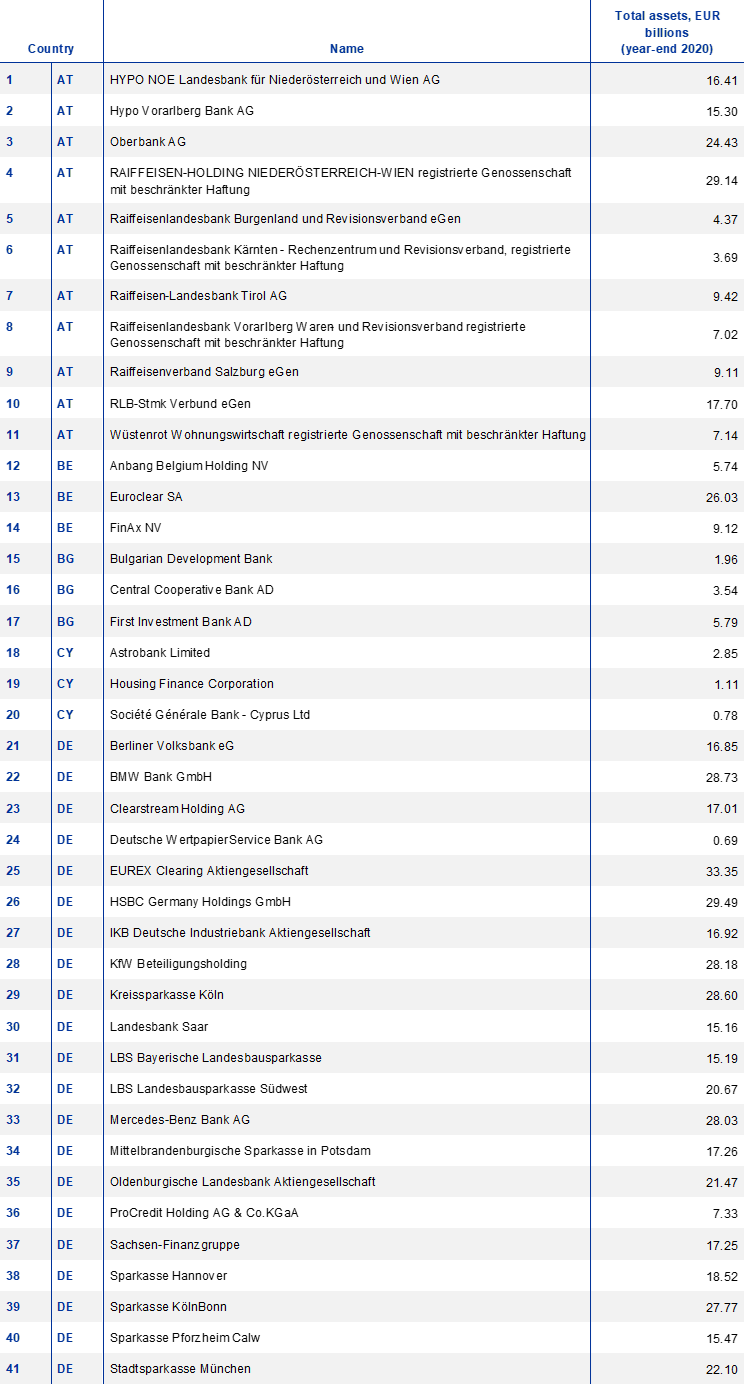

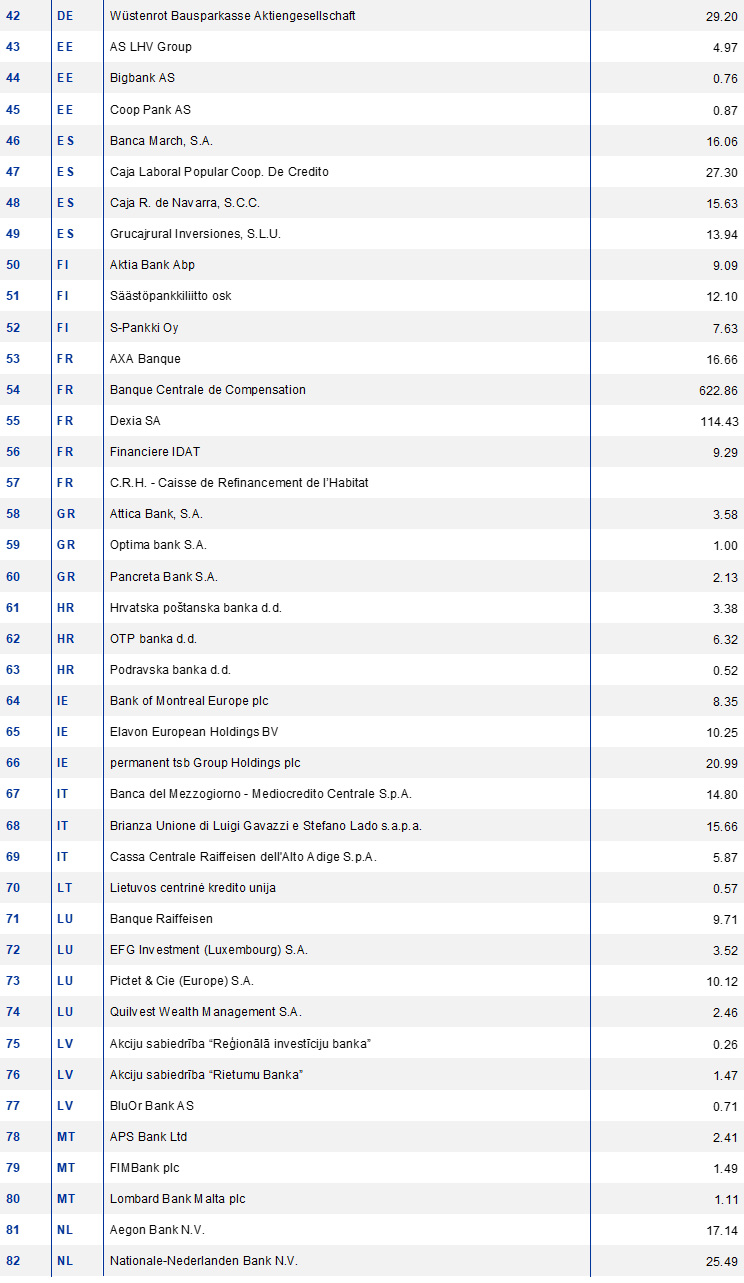

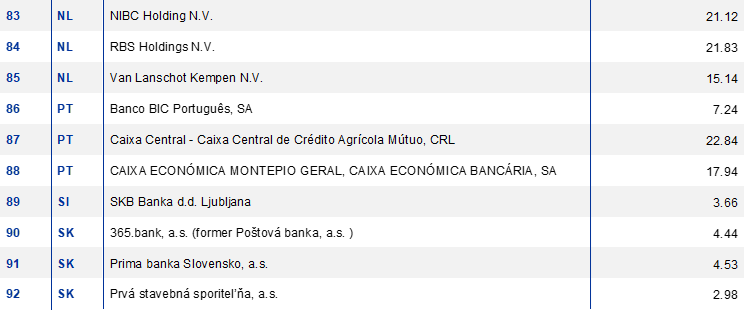

Table 1

Number of LSIs and related classification by country

Note: High-impact column includes FMIs.

2.3 LSI business models

The business models of the LSI sector vary considerably across different countries and have also evolved over time, being impacted by Brexit and fintech for instance. The predominant business model remains retail banking, but LSIs are also present in a variety of dynamic market segments ranging from corporate lending and asset management to more specialised products such as car finance and custodian services. The LSI sector includes FMIs with a banking licence. More recently the sector has witnessed the emergence of digital-only banks focusing on specific business lines such as retail, payments or B2B[15] products (such as use of APIs).

While retail banking is still key to European LSIs, there are also a number of very specialised niche players.

Compared to SIs, the activities of LSIs tend to be more geographically concentrated, with many servicing smaller communities according to their location. This is especially relevant for cooperative banks operating in parts of the euro area. The product portfolios offered by LSIs also tend to be more specialised than those of SIs. Some specialise in car financing, mortgage banking, providing solutions and loans to homeowners’ associations, lending to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), operating as service providers for securities, granting loans in connection to life insurance in the secondary market, etc. LSIs focusing on retail clients face many of the same challenges as SIs: weak profitability in the low interest rate environment, competition from both digital banks and non-bank fintech entities, and the need to digitalise and improve IT infrastructure. These challenges are particularly pronounced in jurisdictions that already have a high level of competition.

In addition to the reduction observed in the number of LSIs over the last few years, the composition of types of business model has also evolved over time. While the LSI sector remains heavily oriented towards retail banking, the share of retail lending institutions has steadily decreased, both in terms of the number of LSIs and in terms of the total assets of the LSI sector. The continued decrease in the number of LSIs focused on retail lending can be attributed to the consolidation trend that has been under way since the inception of the SSM, as well as more recent developments related to fintech businesses applying for banking licences.

Chart 4

Structure of the LSI sector by business model across countries (by number of entities)

(percentages)

Source: ECB calculations based on the internal business model classification framework.

Note: Number of SSM LSIs (excluding branches) at the highest level of consolidation (incl. FMIs).

3 Key developments in the LSI sector

Legacy issues and new challenges are delaying a recovery in profitability; this could threaten the current comfortable levels of capital.

Similar to many other industries, the banking sector has been going through a period of significant uncertainties and it seems unlikely this will change in the near future. While immediate risks from the pandemic have not materialised to the extent initially expected, not least due to massive policy interventions, new ones have emerged. Balance sheets and the loan business grew moderately in 2021, but LSIs continue to face weak profitability, as the recovery was mainly driven by lower loan loss provisioning. Costs remain elevated and earnings, especially NII, continue to be threatened by the low interest rate environment that persisted in 2020 and 2021 at least. Against this background, capital levels have weakened, but for the time being remain comfortable on average; liquidity is not a key concern. In the light of the increased uncertainties from geopolitical and macroeconomic tensions, however, LSIs have to prepare for an environment of potentially volatile asset prices as well as increased inflation and interest rates. This is likely to increase the challenges to adequate loan and deposit pricing and potentially see some LSIs facing higher funding costs and a rise in non-performing exposures. Moreover, new risks are emerging: increased operational risks in conjunction with IT and cyber issues and environmental, social and governance (ESG) challenges. LSIs need to improve their risk-bearing capacity and risk management (see also the LSI thematic review on governance[16], Section 3.3.4).

3.1 Balance sheet composition

Overall balance sheet growth driven by loan business and increased cash positions…

The aggregate LSI sector balance sheet grew by €189 billion or 4.1% in 2021.

The aggregate balance sheet of the LSI sector grew by €189 billion or 4.1% to €4,794 billion, roughly the same pace as SIs in Europe (3.79%). This was driven by growth in the loan portfolio (+2.8%) and a significant increase in cash balances at central banks and other demand deposits (+19.1%). Loans to non-financial corporations (NFCs) (+4.3%) and households (HHs) (+3.0%) dominated the absolute growth in the loan business. Performance was generally comparable to SIs, which expanded their loans to HHs and NFCs slightly more strongly, at the expense of growth in loans to credit institutions and other financial corporations.

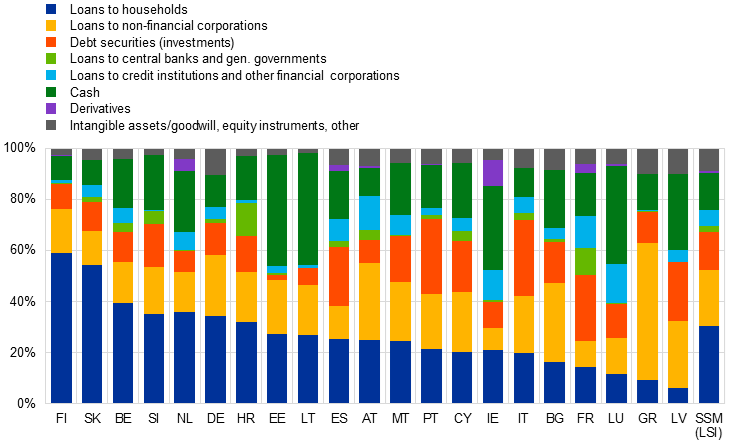

Assets: … but there were differences in pace and composition across European LSIs

Asset growth differs from country to country, often due to idiosyncratic drivers; loans to households and non-financial corporations remain the core of the business, with cash also remaining relevant.

At country level, changes in LSI assets and liabilities over the course of 2021 showed significant heterogeneity: material decreases in total assets in some countries contrasted with strong growth in others, the latter cases sometimes being influenced by the emergence of new entities with fintech-driven business models.

More than half of the assets in the European LSI sector relate to loan exposures to HHs and NFCs. Portfolio composition varies widely at country level; the shares of HHs and NFCs range from less than 10% to over 80%, with similar variance in the shares of individual sub-segments within HH and NFC portfolios (e.g. residential and commercial real estate). In some countries, non-loan exposures such as debt securities are significant, while in others, cash reserves are high, which may suggest difficulties in growing the loan business.

Chart 5

Composition of assets of LSIs: fourth quarter 2021

(percentages)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities, FINREP F 01.01, FINREP F 01.01_dp, FINREP F 18.00a, FINREP F 18.00a_dp.

Notes: Number of SSM LSIs (excluding branches) at the highest level of consolidation (excl. FMIs). Loan breakdown based on gross loan amount; remaining balance sheet positions are reported in carrying amounts.

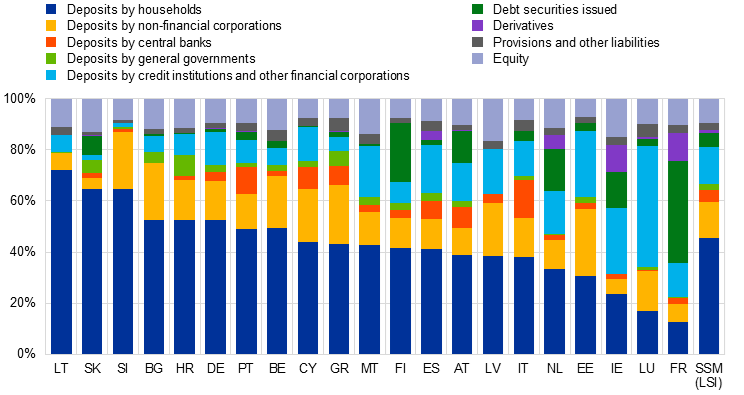

Liabilities: household deposits remain the main source of funding

As shown in Section 3.5, European LSIs generally rely heavily on deposits from households as their key funding source. These account for around 45% of total LSI liabilities and equity, with significantly higher shares in some countries. Asset growth has been funded predominantly by collecting additional deposits, largely from NFCs and HHs, as restrictions during the pandemic led to a temporary reduction in consumption and investment, supporting savings by non-financial counterparties and consumers. Increased funding from central banks – including TLTROs – and deposits from other credit institutions have added to the growth in liabilities.

In countries with well-established covered bond and securities markets, debt issuance often plays a considerable role. Central bank funding is relevant in a number of countries too, reflecting past challenges in funding given the sovereign debt crisis in the last decade.

Looking forward, risks relate mainly to the ability of LSIs to replace ECB funding and deal with increasing funding costs as rates rise, possibly combined with impeded access to wholesale funding markets.

Chart 6

Composition of liabilities for LSIs: fourth quarter 2021

(percentages)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities, FINREP F 01.02, F 01.02_dp.

Note: Number of SSM LSIs (excluding branches) at the highest level of consolidation (excl. FMIs).

3.2 Profitability

Profitability remains weak for LSIs; the partial recovery in 2021 was largely driven by a significant decline in provisioning.

The return on assets (RoA) for LSIs recovered from 0.17% in 2020 to 0.34% in 2021, despite the growth in total assets, while both the number of loss-making entities and the magnitude of losses fell. The return on equity (RoE) rose even more sharply from 1.8% to 3.5%, reflecting the lower growth in equity. However, the recovery was less strong than in the SI sector, where RoA increased from 0.1% to 0.43% and RoE from 1.53% to 6.70%.

Profitability remains weak; the main benefit in 2021 came from lower provisioning, but NII declined further.

In most countries, there were net releases of impairments and provisions. Net provisioning by LSIs on average in the SSM was -3.5% in the fourth quarter of 2021 as a percentage of operating income and -0.08% as a percentage of total assets. These releases have had a strong positive impact on profits, but they also have to be seen in the light of legacy credit risk issues and expiring coronavirus moratoria.

NII, on the other hand, declined 4.3% compared to the end of 2020, despite the growth in lending described above, reflecting the ongoing low interest rate environment. Relative to total assets, NII decreased to 1.17% from 1.27% the year before, a drop which occurred in nearly all countries. National differences were caused by different levels of loan growth, and sometimes by special niche players. Raising funds under TLTROs provided a way for LSIs to generate additional NII, resulting in a quite strong positive effect on profits.

LSIs were successful in growing their net fee and commission income (NFCI) in 2021. This rose 11.4% year-on-year and contributed 24% of the overall change in aggregate profits. Relative to total assets, NFCI increased from 0.74% to 0.79% for the sector, more than compensating for the relative decline in NII.

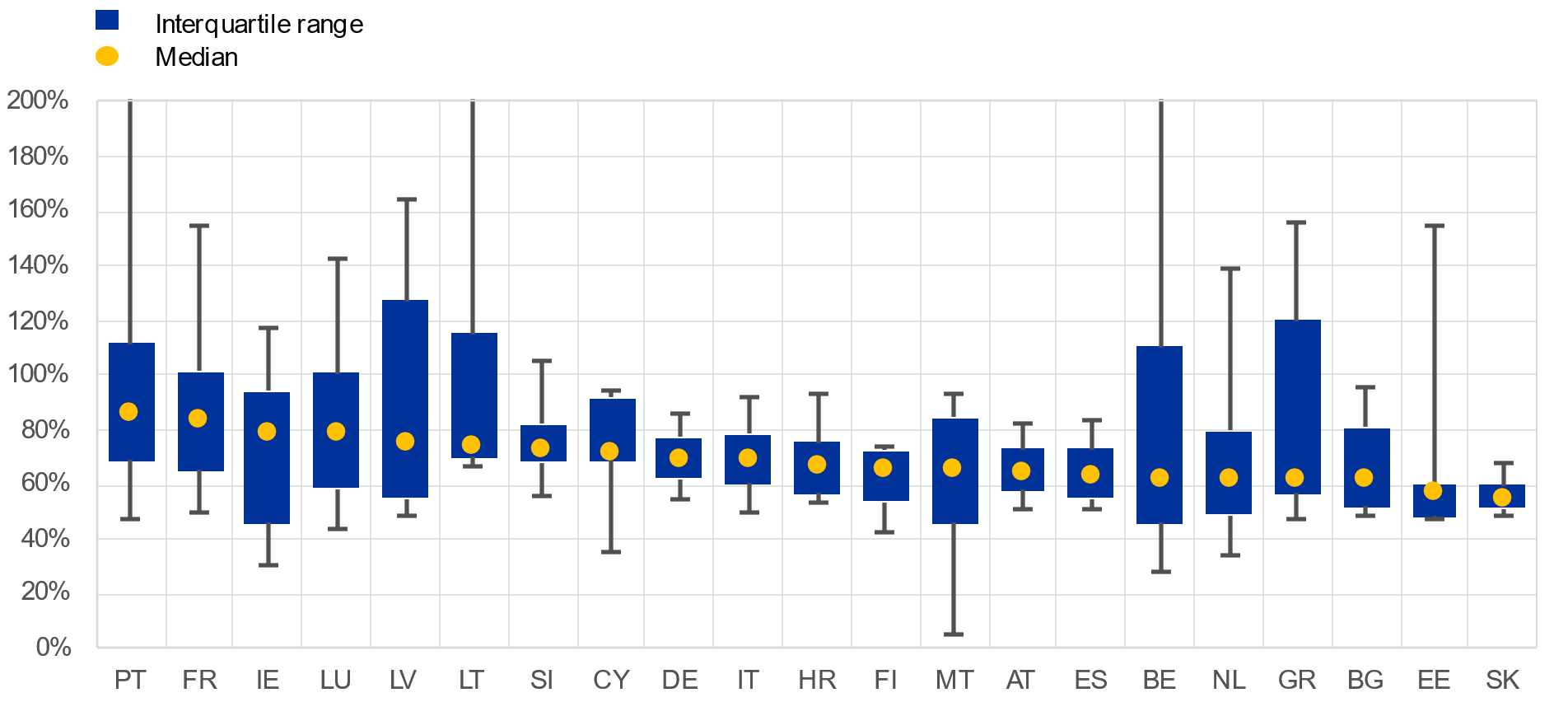

The cost/income ratio stood at 70.2% for the LSI sector in 2021, above the 64.3% level observed for SIs despite a 1.4 percentage-point reduction compared with the fourth quarter of 2020 (SIs saw a fall of 1.74 percentage points). There were major differences across countries, caused by ongoing restructuring efforts, strong loan growth or access to new revenue pools, such as crypto assets, in some cases, and the specific structure and nature of national banking sectors. In some countries strengths often reflect very specialised business models and niche players with the ability to exploit attractive margins in their areas of activity.

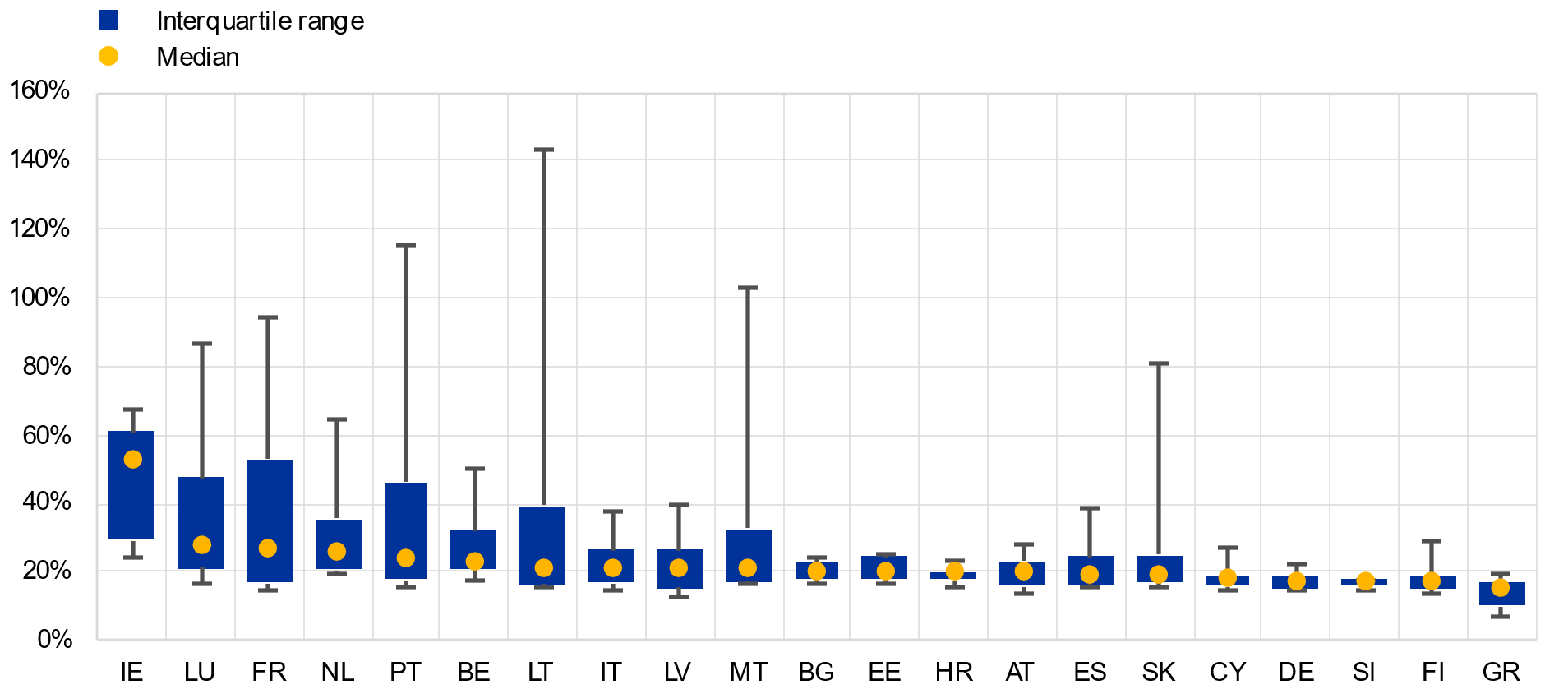

Chart 7

Cost/income ratio

(percentages)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities, FINREP F_02.00, F_02.00_dp, SPE.DPI.

Notes: The chart displays the 10th and 90th percentiles (narrow bars), the median (mark in the box) and the interquartile range between the 25th and 75th percentiles (the thick bar) for end-of-quarter values during 2021. Number of SSM LSIs (excluding branches) at the highest level of consolidation (excl. FMIs). 23 banks were excluded as their values were outside the range displayed. Values outside axis range are PT (282%), LT (1,446%), BE (495%).

Profitability at country level improved, but the number of loss-making entities remains high in some countries.

This general recovery in profits was observed across all countries, with very few exceptions. Dispersion across and within countries is material, however, with small pockets of both highly loss-making and very profitable entities. In total, there were 115 loss-making entities in the LSI sector in 2021 (5.5% of total entities at the highest level of consolidation), compared to 164 (7.5%) in 2020. Factors behind country-level concentrations include the share of new fintech entities still in the start-up phase and the hub nature of several LSIs acting as an entry point to the European banking sector.

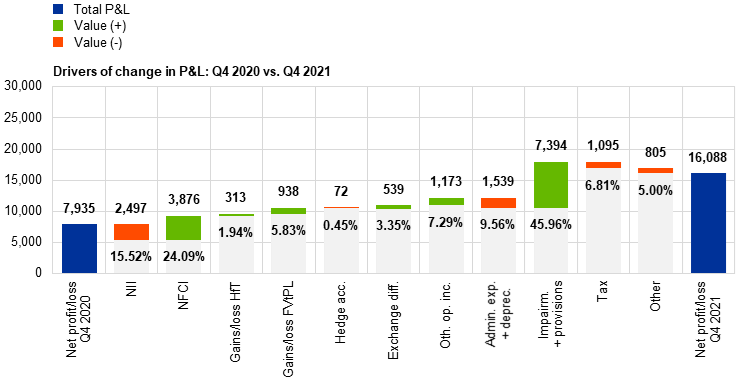

Chart 8

Change in year-end results for LSIs: 2020 vs. 2021

(EUR millions, percentages)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities, F_02.00, F_02.00_dp.

Notes: Number of SSM LSIs (excluding branches) at the highest level of consolidation (excl. FMIs). Percentages refer to nominal change vs. total profit in 2021.

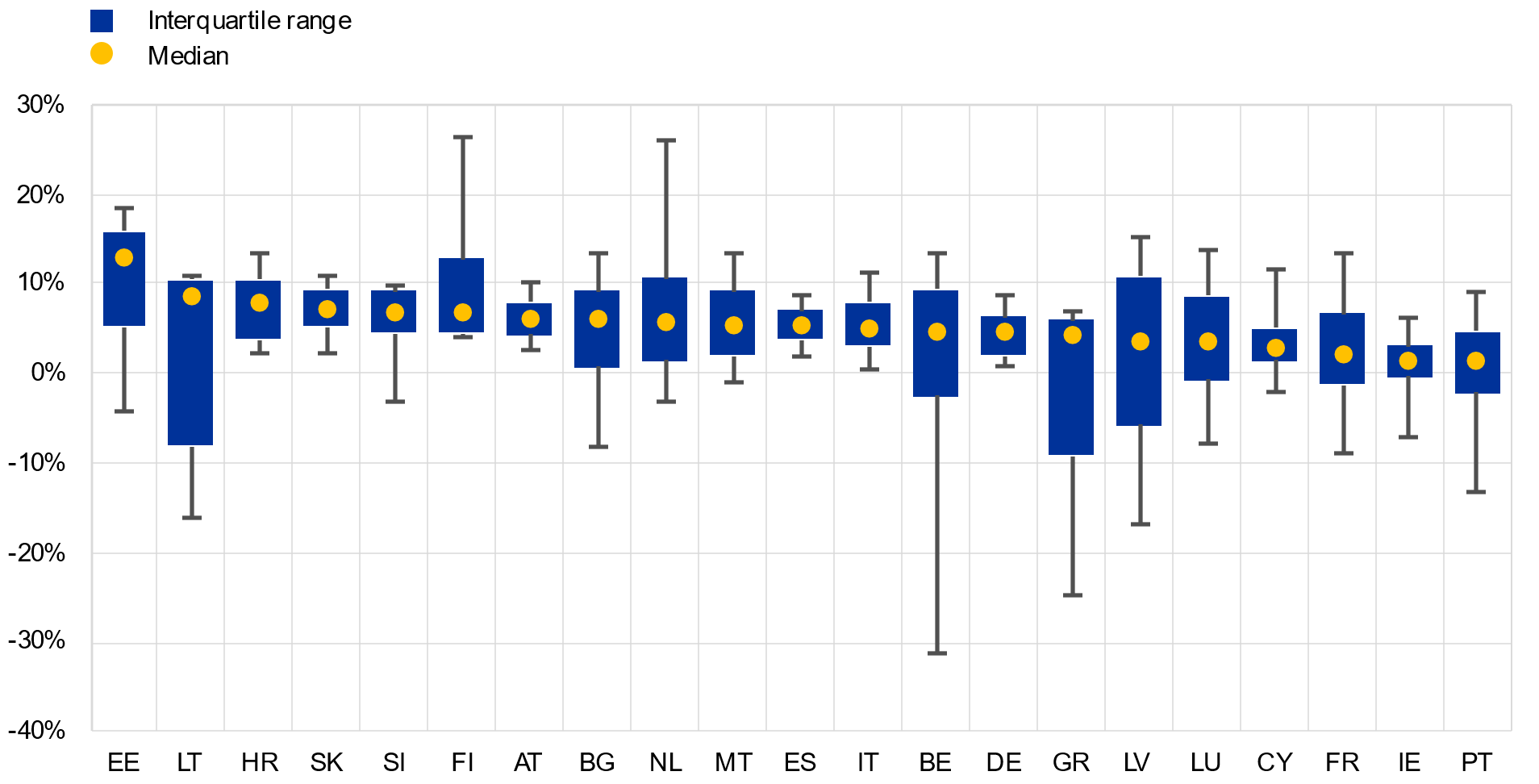

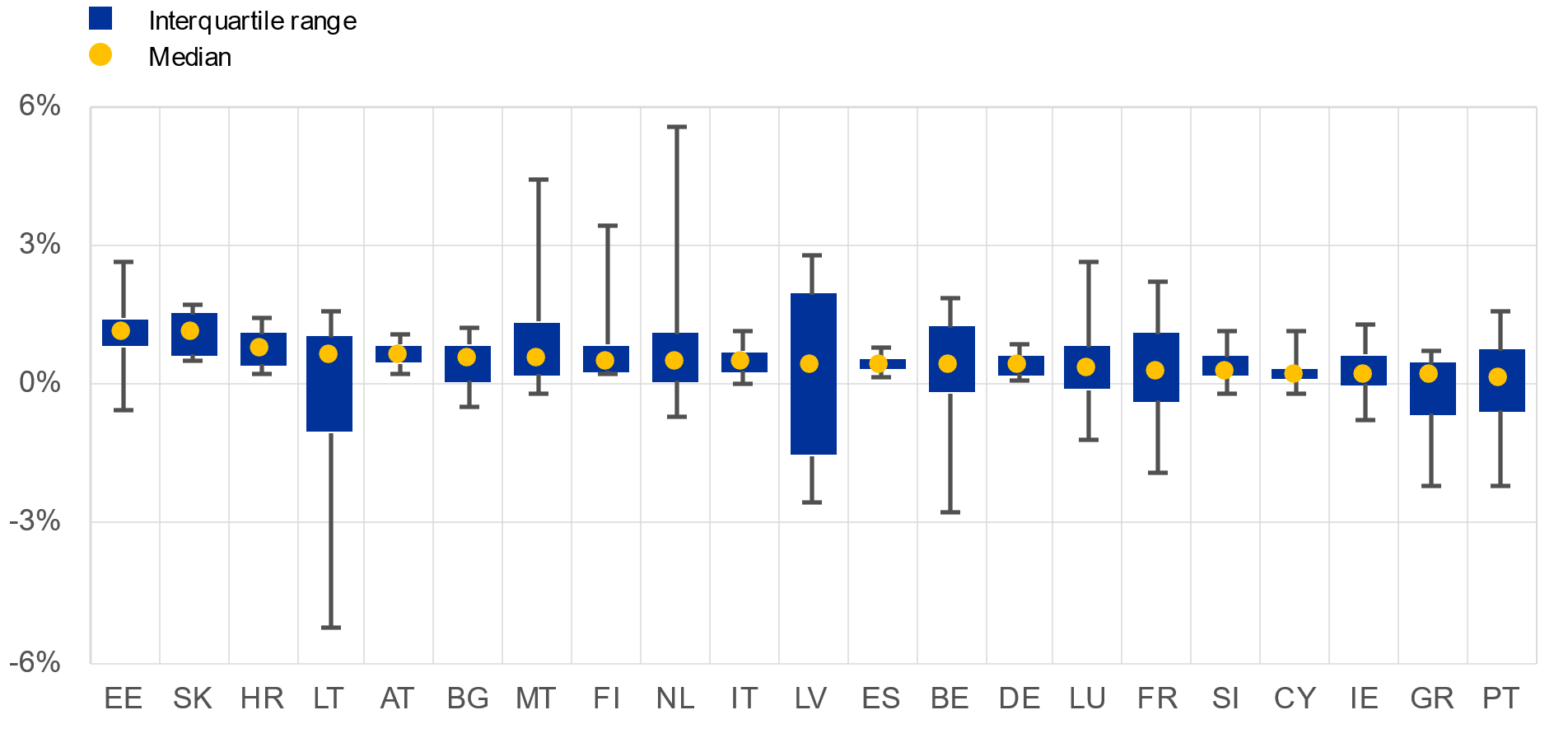

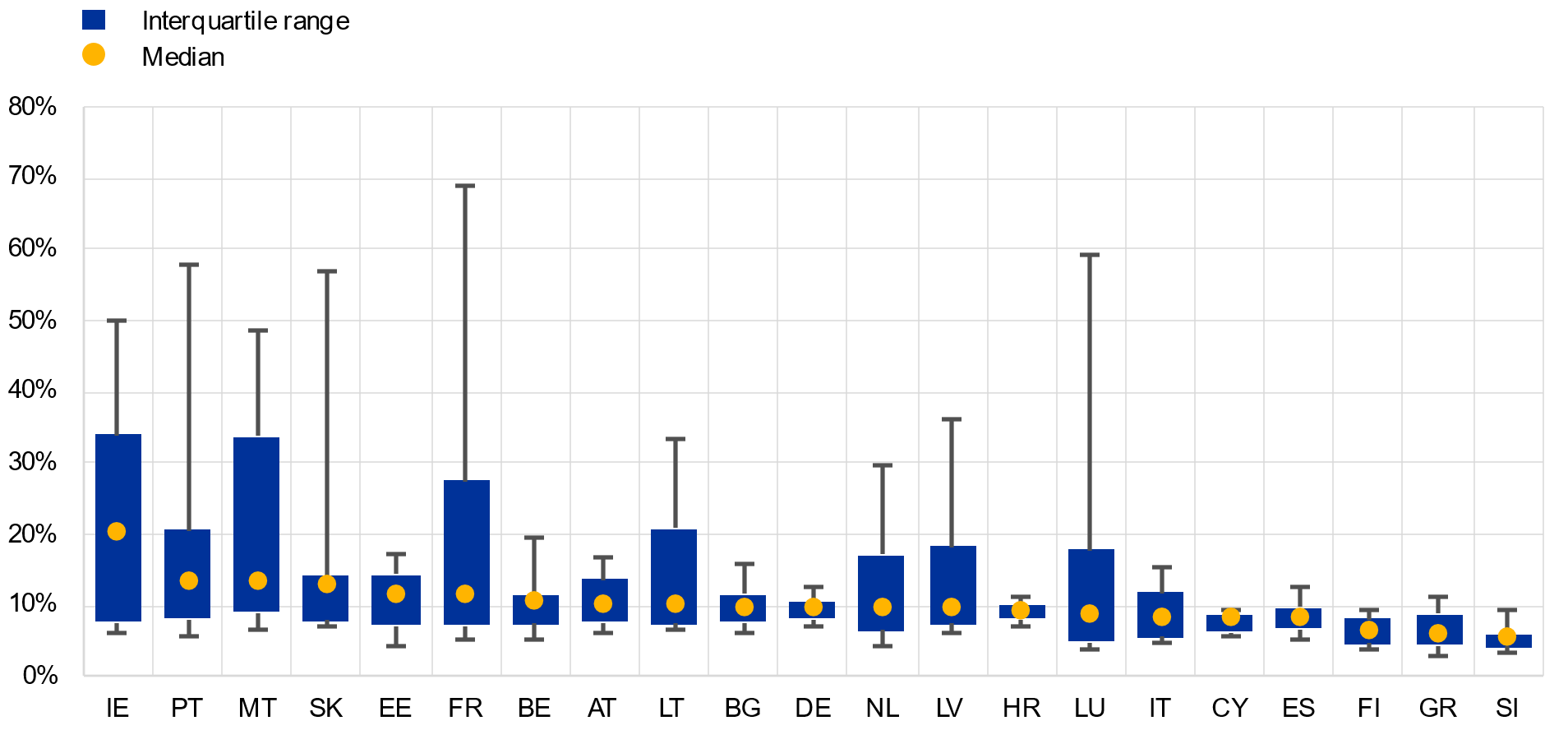

Chart 9

Annualised RoE and RoA by country

a) Return on equity (RoE)

(percentages)

b) Return on assets (RoA)

(percentages)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities, F_02.00, F_02.00_dp.

Notes: Charts display the 10th and 90th percentiles (narrow bars), the median (mark in the box) and the interquartile range between the 25th and 75th percentiles (the thick bar) for end of quarter values during 2021. Number of SSM LSIs (excluding branches) at the highest level of consolidation (excl. FMIs).

Window of opportunity to realise sustainable profit levels may close quickly.

Overall, the sector still has not overcome its weak profitability. LSIs remain under pressure to improve their capacity to generate bottom-line profit while also cutting costs, but without damaging the robustness of their operations and risk control functions. Some LSIs have been successful in dealing with legacy issues and carefully tapping into new areas of business to support profitability. Given the challenges from a macroeconomic perspective and the uncertainties over the impact of rising interest rates in the medium to long term, the window of opportunity to make the required changes and realise a sustainable profit level may close quickly.

As of second quarter 2022 the profitability for LSIs has worsened again with a significant deterioration in the cost/income ratio to 87.7%, driven mainly by a small number of countries, which also translated into a drop in RoE to 1.06%. This was mainly driven by sizable valuation losses experienced in one country as a consequence of increasing interest rates and the way these impacted the balance sheets in the respective accounting regime. Importantly, as a result of rising interests most banks in that country are required to book losses (strict lower-of-cost-or-market principle) in their securities portfolios, which are however in many cases temporary in nature.[17] In the long term, rising interests should increase the profitability of banks in this country as well. In the majority of countries LSIs were able to improve their return compared to the previous year, as net interest income (+6.2% YoY) and net fee and commission income (+4.3% YoY) as well as income from trading activities (+74% YoY) were increasing.

3.3 Credit risk

Credit risk remains crucial for both profit and capital adequacy…

Regardless of the continuous decrease in NPL levels, credit risk remains a key source of concern given the high stock of non-performing loans at numerous entities, especially in the light of newly emerging risk factors. As described above, profitability remains highly dependent on provisioning, confirming the supervisory treatment of credit risk as a key priority and underlining the rationale behind the continued push for banks to improve the quality of their loan books and their risk management capacities.

…but NPL levels are improving only gradually and high levels of non-performing assets persist.

LSIs’ aggregate NPL ratio at SSM level – using the EBA definition including cash balances at central banks and other demand deposits – exhibited a steady continuation of previous years’ downward trend to 1.8% at the end of 2021 despite the pandemic (2018: 2.2%; 2016: 4.4%), an evolution that was consistent internationally. In some countries, overall NPL ratios declined even though default rates remained high, thanks to sizeable NPL outflows from sales/securitisations by some LSIs. However, NPL levels are continuing to diverge across countries.

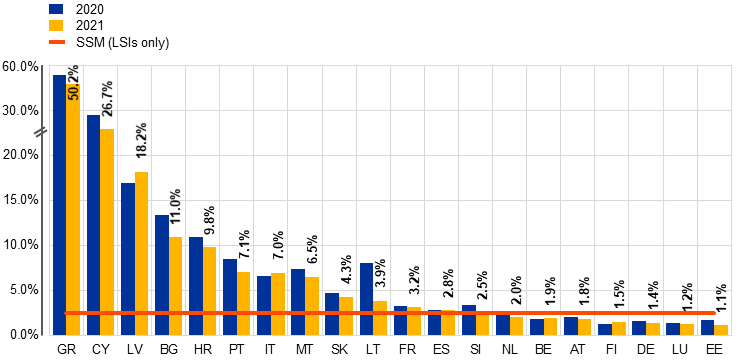

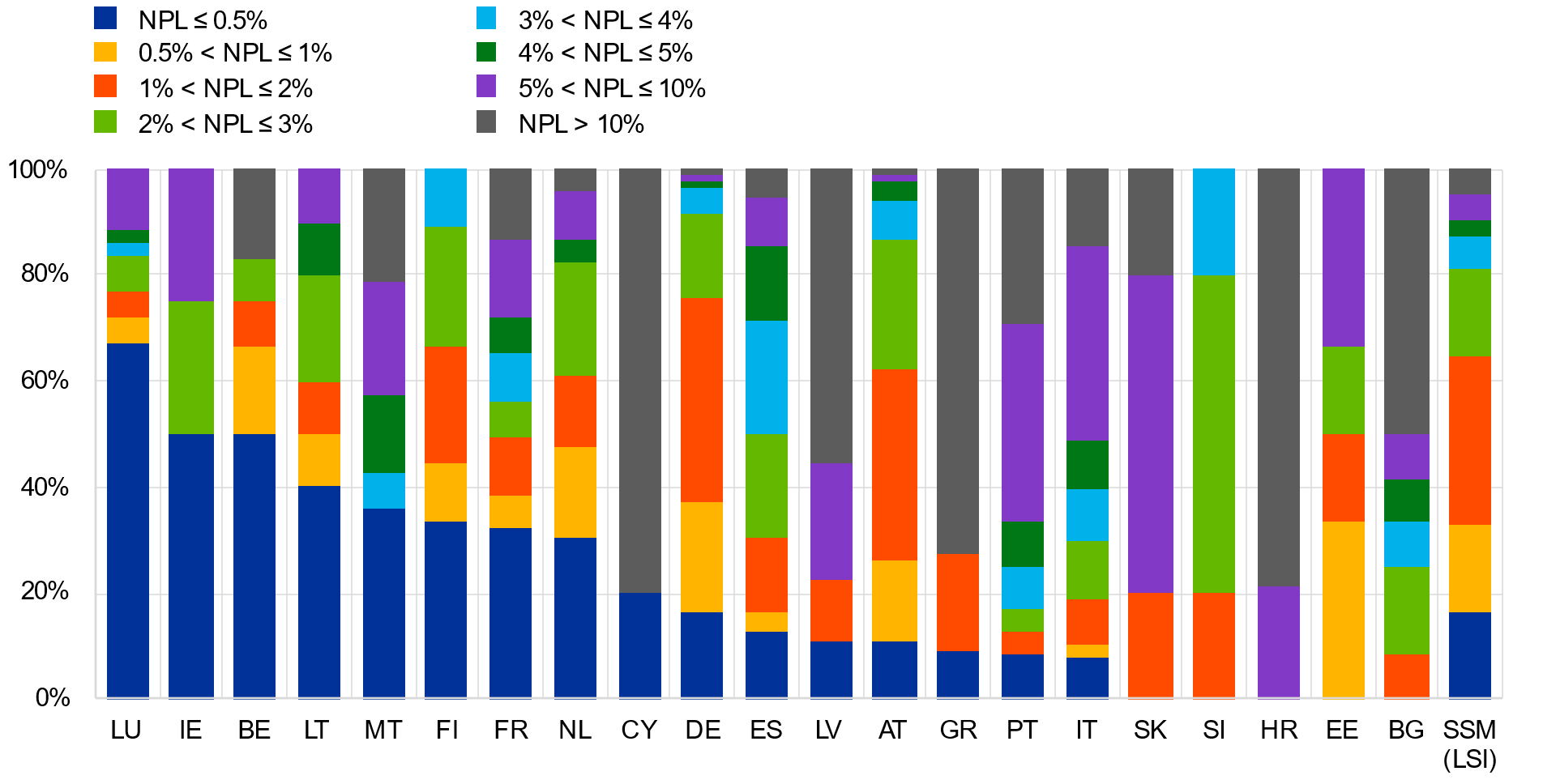

Chart 10

NPL ratios (excluding cash) by country

(percentages)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities, FinRep F_18.00a, F_18.00a_dp.

Note: Number of SSM LSIs (excluding branches) at the highest level of consolidation (excl. FMIs).

Success in dealing with legacy NPLs depends largely on individual banks’ willingness and ambition to tackle these exposures.

Even countries with low average NPL ratios often have a significant number of individual LSIs with high levels of NPLs, and vice versa. This suggests that applying successful strategies to deal with legacy NPLs does not necessarily depend on country specificities, but is largely driven by the ambition and capacity of individual banks to reduce them. In total, 97 SIs had an NPL ratio of more than 10% at the end of 2021 (compared to 118 at the end of 2020). The share of high-NPL banks is elevated in a number of countries. However, some banks have a commercial strategy which focuses on riskier client segments and charge higher interest rates to compensate for what will by definition be a higher level of NPLs.

Chart 11

LSI clustering by NPL clusters (excluding cash)

(percentages)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities, FINREP F_18.00a, F_18.00a_dp.

Note: SSM LSIs (excl. branches) at the highest level of consolidation.

As described above (see Section 3.1), heterogeneity in counterparty composition is a key feature of LSI loan books and needs to be considered prominently in all country and sector-level analyses of credit risk profiles. As is the case with SIs, NFCs account for the bulk (more than two-thirds) of LSI NPLs, with SMEs and commercial real estate constituting highly material and particularly risky sub-segments. In the residential real estate sub-segment, which accounts for the largest share of the HH portfolio for LSIs, NPL ratios are generally comparatively low, with a few exceptions at country level.

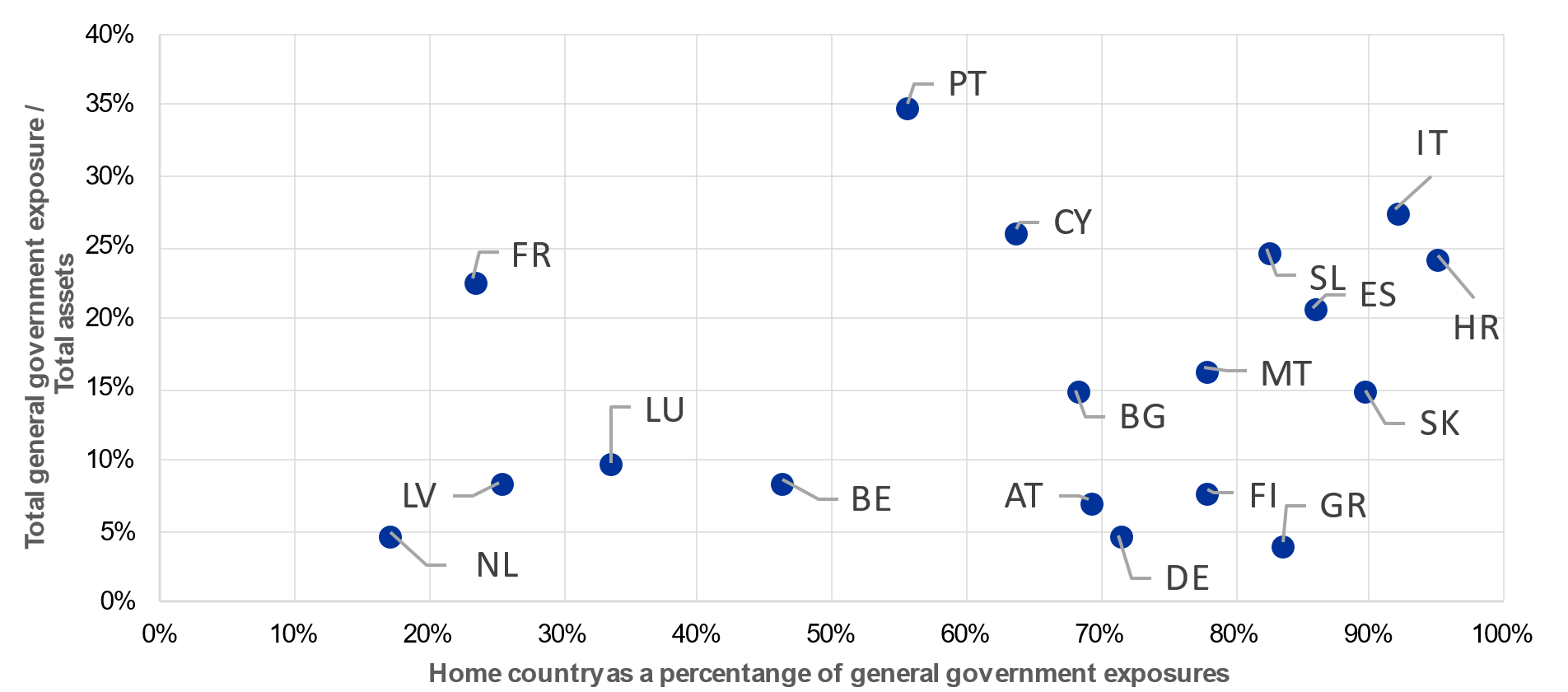

Sovereign exposures remain significant in a number of countries, sometimes exceeding 25% of total assets. A relatively strong bias in favour of sovereign debt of the home country is common; in most countries it exceeds 50%, and in some instances is more than 90%.

Chart 12

Total exposure to general governments by country

(percentages%)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities, COREP C33.00.

Notes: SSM LSIs (excl. branches) at the highest level of consolidation (excl. FMIs). Some countries are not displayed due to methodological confidentiality rules (see Annex D).

Correctly identifying and reporting forborne and unlikely-to-pay (UTP) exposures continues to pose a challenge for LSIs (as for SIs), and this has been exacerbated by factors such as the pandemic and geopolitical events. The cross-country and cross-bank variation observed in forbearance ratios and the share of UTP debtors suggest further supervisory follow-up is needed to distinguish between genuine differences in underlying counterparties’ riskiness and potentially lax identification and reporting practices. In similar fashion, the variance in LSIs’ provision levels considered against the background of NPL vintages and benchmarking against SI peers suggests continued supervisory focus on provisioning practices is warranted.

Box 2

Coronavirus (COVID-19) risks in the LSI sector

Moratoria and pandemic-related forbearance measures were key tools used by banks to manage the impact of the coronavirus pandemic. The shares of LSI loan books subject to these measures over the course of the pandemic reflected the relevance of these; country-level LSI averages exceeded 10% in some jurisdictions at the end of 2020. Bank-level data for the same reference date showed significant intra-country variation, with individual LSIs from eight countries using such measures on as much as 20-50% of their loan books, while for 119 institutions the share exceeded 10%. Across the board, SME portfolios were subject to particularly elevated shares of moratoria.

According to LSIs’ reporting, the bulk of these measures were subsequently phased out over the course of 2021, reducing their share of aggregate LSI loans to 0.3%, down from 1.4% at the end of 2020, and the number of LSIs where they covered more than 10% of the total loan book to eight, down from 119. Generally, pandemic risks seem not to have materialised to the extent initially feared, not least thanks to the massive policy measures that were put in place.

The ECB provided several reliefs and support mechanisms to banks in the euro area, both from the monetary policy side, such as swap facilities and additional liquidity, and from the supervisory side. These included allowing discretion in meeting supervisory timelines or deadlines and pursuing procedures, permitting temporary use of capital and liquidity buffers and introducing supervisory flexibility in the treatment of non-performing loans.

Back in 2020 the ECB granted flexibility to NCAs to postpone to 2021 the assessment of LSIs not yet covered by the SREP methodology developed for LSIs. In cases where NCAs decided to apply the methodology to these LSIs in 2020, the plan was that the ECB would initially allow a pragmatic SREP approach covering only the assessment of material risks and leaving Pillar-2-requirement (P2R) and Pillar-2-guidance (P2G) unchanged. The LSI SREP roadmap has been adjusted, with some topics being de-prioritised (e.g. work on P2G was postponed to 2021).

Box 3

Risks in the LSI sector in the light of the Ukraine-Russia conflict

While an early impact analysis revealed that direct exposures to Russia were – with individual exceptions – manageable for banks in aggregate, supervisors have also focused on risks stemming from indirect effects with a more medium-term perspective, such as exposures to vulnerable sectors. Loan-level information on corporate clients (available from the AnaCredit database) has allowed supervisors to identify institutions that seem particularly exposed to these at an early stage and determine what needs to be monitored and followed up on a bank-by-bank basis. European banking supervisors have been reacting quickly, with a contact group to ensure relevant information and expertise is exchanged.

Before the outbreak of the war, the direct exposure of LSIs to Russian, Ukrainian and Belarussian counterparties remained contained at roughly €4.3 billion and was concentrated in a handful of institutions. However, individual banks were affected to varying extents depending on their business model or ownership structure.

Only a small number of LSIs under Russian ownership were affected by being directly subject to sanctions, their owners being put under sanctions and/or their business model being geared towards Russian customers. In some cases, sanctions have required business with key service providers to be discontinued, putting these banks into operational difficulties.

LSIs with operations in Ukraine made major efforts to continue providing banking services to the local population and help staff relocate to safe places where necessary. All LSIs were confronted with the need to provide banking services to refugees arriving in their country.

Supervisors also intensified their monitoring of the more indirect impact of the crisis: financial market volatility and cyber risk. Over the course of 2022 European banking supervisors were deepening their understanding of the medium to long-term consequences and are adapting their engagement and focus areas to the new landscape. The crisis has further highlighted the prominence of credit risk as a major area of attention for banks, along with effective governance arrangements. Outsourcing, IT and cyber risk also remain relevant.

All in all, despite the economic uncertainties in 2021, the observed credit risk impact on the LSI sector has remained limited. Public support for some borrower segments in conjunction with banks’ own moratoria and forbearance measures have most likely played a strong role in this. The risk remains that certain vulnerabilities, in particular asset quality, have only been addressed temporarily and will still materialise going forward, not least considering the new threats arising in the light of geopolitical and macroeconomic tensions, paired with increasing inflation. LSIs’ efforts in cleaning up their loan books and upgrading their risk management procedures to ensure they are compliant with regulatory expectations, such as the EBA Guidelines on loan origination and monitoring, should therefore continue and must remain a key focus for national supervisors.

3.4 Capital adequacy

Capital ratios seem on average adequate, but have declined recently as risk exposures have grown.

At the end of 2021 LSIs’ average overall capital levels seemed comfortable, but this statement needs to be interpreted with caution in light of the sector’s poor ability to generate profits (see Section 3.2), the challenges posed by the economic and business environment as well as non-financial risks such as cyber and IT risk. These all suggest a need for an increase in loss absorbing capacity.

The average total capital ratio of LSIs declined 0.51 percentage points over the course of 2021 to 18.81%. The capital base consisted of more than 90% high-quality CET1 in nearly all countries. LSIs’ CET1 ratio declined 0.39 percentage points to 17.32%, despite a 3.2% (€12.9 billion) increase in CET1 capital, because total risk exposures rose by an even stronger 5.6% (€125.6 billion), exceeding the growth in balance sheets. Across countries the average CET1 ratio ranged from 10.3% to 35.6%. For SIs too the CET1 ratio stood slightly lower at 15.6% (year-end 2020: 15.7%), as risk exposures increased more strongly than CET1 capital.

Chart 13

CET1 ratio and total capital ratio by country

a) CET1 ratio

(percentages)

b) Total capital ratio

(percentages)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities, COREP C 03.00.

Notes: The chart displays the 10th and 90th percentiles (the narrow bars), the median (mark in the box) and the interquartile range between the 25th and 75th percentiles (the thick bar) for end-of-quarter values during 2021. SSM LSIs (excl. branches) at the highest level of consolidation (excl. FMIs).

The number of LSIs with a low CET1 ratio remains limited, with only 16 in total across all countries reporting a figure below 10%.

In terms of risk exposure density, i.e. risk exposure over total assets, the average across LSIs stands at 49.7%, meaning that each euro of exposure translates into about 50 cents of risk amount. The density for LSIs is higher than for SIs (33.4%) due to the lower reliance on internal models. There is nevertheless significant variety in the LSI sector: some countries have high density ratios, in others the risk exposure amounts to less than 35% of total assets. This may be partly explained by cross-country differences in business models.

LSIs on average exhibit high leverage ratios, but with significant differences across countries and individual entities.

The leverage ratio (fully phased-in) is an additional major capital requirement. This increased 0.71 percentage points to 9.1%, putting it on aggregate well above the 3% requirement. Exposure values decreased, while applicable Tier 1 capital stood higher at the end of 2021. There was, however, significant dispersion in the leverage ratio across LSIs, due to differences in loan growth as well as structural features of banks within countries. As the charts below highlight, there are also significant variations even within the same country.

Chart 14

Leverage ratio by country

(percentages)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities, COREP C 47.00.

Notes: The chart displays the 10th and 90th percentiles (the narrow bars), the median (mark in the box) and the interquartile range between the 25th and 75th percentiles (the thick bar) for end of quarter values during 2021. SSM LSIs and branches at the highest level of consolidation (excl. FMIs).

Given legacy issues, new risks and continued weak profits, banks need to ensure they are properly capitalised under Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 in adverse scenarios.

Overall, capitalisation still seems comfortable, but this needs to be weighed against potentially increasing risks and the low capacity of many LSIs to generate profits. Access to capital markets may be limited for various reasons, especially for smaller institutions, so retained earnings are a key source to strengthen capital. LSIs also need to reflect the potential future impact from first and second-round effects of exposures to borrowers hit by the crisis on their balance sheet and capital adequacy in their planning. Already as of the second quarter 2022 capital levels have been declining on aggregate to a CET1-ratio of 17.1% and a total capital ratio of 18.5%; a trend that was common in nearly all countries..

3.5 Funding and liquidity

Liquidity risk in the LSI sector was limited on aggregate in 2021, but remains vulnerable to sudden shifts and hence deserves attention from banks and supervisors alike.

LSIs’ liquidity position in 2021 benefited from a significant increase in deposits. On aggregate, asset growth was funded predominantly from additional deposits, largely from non-financial corporations and households. Given the challenges in funding markets during the pandemic, SIs were keen to raise deposits from households, leading to a significant growth in their funding from this source (+€486.9 billion or 7.5%). In relative terms the growth was far less pronounced for LSIs (+€16.7 billion or 0.8%). The LSI sector increased its stock of debt securities outstanding by €15.2 billion or 6.3%; the change for SIs was lower at +€18.2 billion or 0.5%.

Deposits from households and non-financial corporations grew strongly, as did central bank liabilities, supported by TLTRO transactions…

Increases in central bank funding also played a major role in 2021, supported by TLTRO transactions. As part of the ECB’s TLTRO transactions, a total of €224 billion was allocated to 769 LSIs, improving their interim funding position. While on country aggregate the cash balances at central banks usually exceeded the drawn amounts, meaning that TLTROs can be repaid from that cash, this looked different at individual bank level and 44 institutions held current cash levels with the central bank that were not sufficient to repay TLTROs and would have to replace these with other, more expensive sources of funding.

…which also translated into changes in the LCR, that remained at comfortable levels on aggregate.

The liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) of LSIs, one of the two key supervisory metrics, fell from 220.7% to 201.2% on aggregate, as the net outflow increased at a greater rate (+17.9%) than the liquidity buffer (+7.5%). The corresponding figure for SIs stood at 173%, largely unchanged compared to the fourth quarter of 2020. The LCR differs significantly across countries, however. It should be noted, however, that a temporary breach does not necessarily trigger direct supervisory measures, as entities are first required to submit a credible plan for restoring compliance to the supervisor.

The NSFR stood at 133.3%, slightly above the ratio for SIs (129.4%). Dispersion across countries remains more limited than for the LCR, with average values mostly between 125% and 170%.

The loan-to-deposit ratio (LtD ratio) seems to follow regional characteristics, as the LSI sectors in four eastern and south-eastern European countries show the lowest value for this metric. Generally, the LtD ratio for SIs follows that of LSIs in terms of country characteristics, pointing to structural features of the respective economies.

The amount of unencumbered assets is a crucial element of contingency funding. The ratio of unencumbered assets remains high throughout the European LSI sector, according to country averages. The average for all LSIs across Europe is 83.2%, slightly higher than for SIs (76.7%). Hence on paper, access to secured funding by using unencumbered assets seems a valid option. For individual LSIs, of course, this depends very much on the quality and amount actually available, as not all assets may be suitable for being pledged as collateral.

Funding concentration increased slightly by roughly 100 basis points in 2021 to 19.6%, following stronger growth in the amounts collected from the top ten funding counterparties per institution, mainly in the third and fourth quarters. We see a high funding concentration in the top ten counterparties in some countries; this is partly driven by strong intragroup links and asset management footprints.

Liquidity risk profiles can change at short notice, so banks need to be attentive to their liquidity position and prepare for exit from TLTRO.

As stated above, liquidity risk can hit both individual banks and whole sectors at very short notice. Hence, despite the comfortable situation at the end of 2021, banks need to be very attentive to their ability to replace central bank funding acquired from TLTROs and deal with potential reversals in deposit flows. Generally, given the increased uncertainties stemming from geopolitical and macroeconomic tensions, banks should prepare for scenarios of increasing challenges to funding in terms of cost or access, even if they currently have high levels of unencumbered assets. This needs to be closely monitored by national supervisors as well.

3.6 The LSI sectors of Bulgaria and Croatia at a glance

The level of KRIs at new entrants remains comfortable.

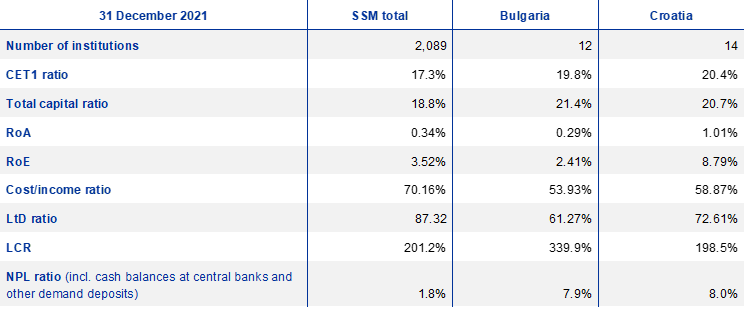

Profitability indicators for Croatian LSIs were above the SSM LSI average,[18] with RoE standing at 8.79% and RoA at 1.01%. For Bulgarian LSIs, profitability stood roughly in line with the SSM average, with RoE of 2.41% and RoA of 0.29%. In terms of cost efficiency, the cost/income ratio of Croatian LSIs stood at 58.9%, while in Bulgarian LSIs it reached 53.9%, both well below the SSM average. Asset quality is under focus in both countries, with NPL ratios[19] amounting to 8.0% at Croatian LSIs and 7.9% at Bulgarian LSIs. NPL coverage at Bulgarian LSIs remained at 33.5%, slightly below the SSM average, while for Croatia it stood at 62%, significantly above the average. Both countries’ LSIs show solvency and liquidity levels above the SSM average. In Croatia, the average CET1 ratio stood at 20.4% and the LCR was 198.5%, while in Bulgaria the average CET1 ratio was 19.8% and the LCR was 339.9%.

Table 2

Key risk indicators for Bulgaria and Croatia

(number; percentages)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities.

Notes: SSM LSIs (excl. branches) at the highest level of consolidation (excl. FMIs). Some countries are not displayed due to methodological confidentiality rules (see Annex D).

3.7 The supervisory view of risks

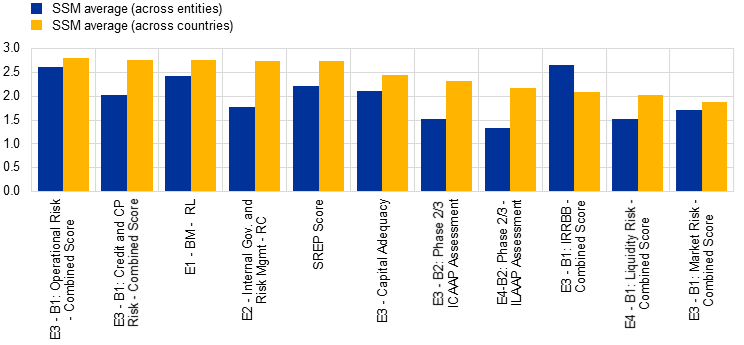

In their annual assessments, supervisors carry out a comprehensive review of the risk situation in the individual LSIs. Overall, the SREP assessments performed in 2021 using the end of 2020 as the reference date (and which most likely also took developments that occurred even after the reference date into account) resulted in an average score of 2.75, slightly worse than 2020 (2.70). Operational risk was the supervisory risk category that received the lowest average score on the four-step SREP scale, at around 2.81. This was most likely the consequence of the generally increased relevance and openness of IT infrastructure, resulting in cyber risks, and challenges to the operating environment revealed by the pandemic. Next came credit risk, averaging 2.79. As in previous years, concerns around business models (2.76) and governance (2.75) also remained prominent. In light of the significant amount of liquidity in the market, supported by central bank operations and increased customer appetite for savings, liquidity risk is rated positively, with scores along the different dimensions ranging between 1.8 and 2.2. Short-term liquidity risk, however, experienced the strongest downgrade of all elements in 2021 compared to 2020, and 571 banks were downgraded by at least one notch. This may have been triggered by uncertainties due to the pandemic.

Supervisory assessments clearly mirror the risk situation, with doubts around profitability and governance, paired with concerns over credit risk.

In terms of average score per country, those countries that are still exposed to the aftermath of the European sovereign debt crisis and banks still facing a high level of non-performing exposures score worse across the SSM. Scores remained broadly unchanged compared to 2020, partly driven by the number of entities for which the SREP is performed at less than annual frequency.

Chart 15

SREP scores per risk dimension (unweighted country averages)

(average score)

Source: ECB calculations based on SSM List of Supervised Entities, NCA supervisory assessments.

Notes: SSM LSIs and branches at the highest level of consolidation (incl. FMIs). Numbers in brackets indicate number of banks per country included in the sample.

As mentioned above, credit risk has been a key supervisory focus in recent years and remains so in the light of recent, newly emerging risks. Consequently, it received the third-worst average score of all elements. A total of 11 countries, however, ranked credit risk more negatively. This clearly shows a cautious outlook. In terms of governance, as many as 13 NCAs out of 21 have a more pessimistic view compared to the year before. Weaknesses in operational risk are also an obvious concern, given the high share of banks scoring 3 or 4. Market risk and liquidity risk seemed to be less of a concern in 2021.

All in all, supervisory assessments confirm the overall risk picture of the European LSI sector as presented within this report. This reflects national specificities, but common denominators nevertheless remain credit risk, governance and risks around business models are key points for attention.

Consequently, supervisory activities were very much centred around these topics, as explained in the next section.

4 Main LSI supervisory priorities and activities

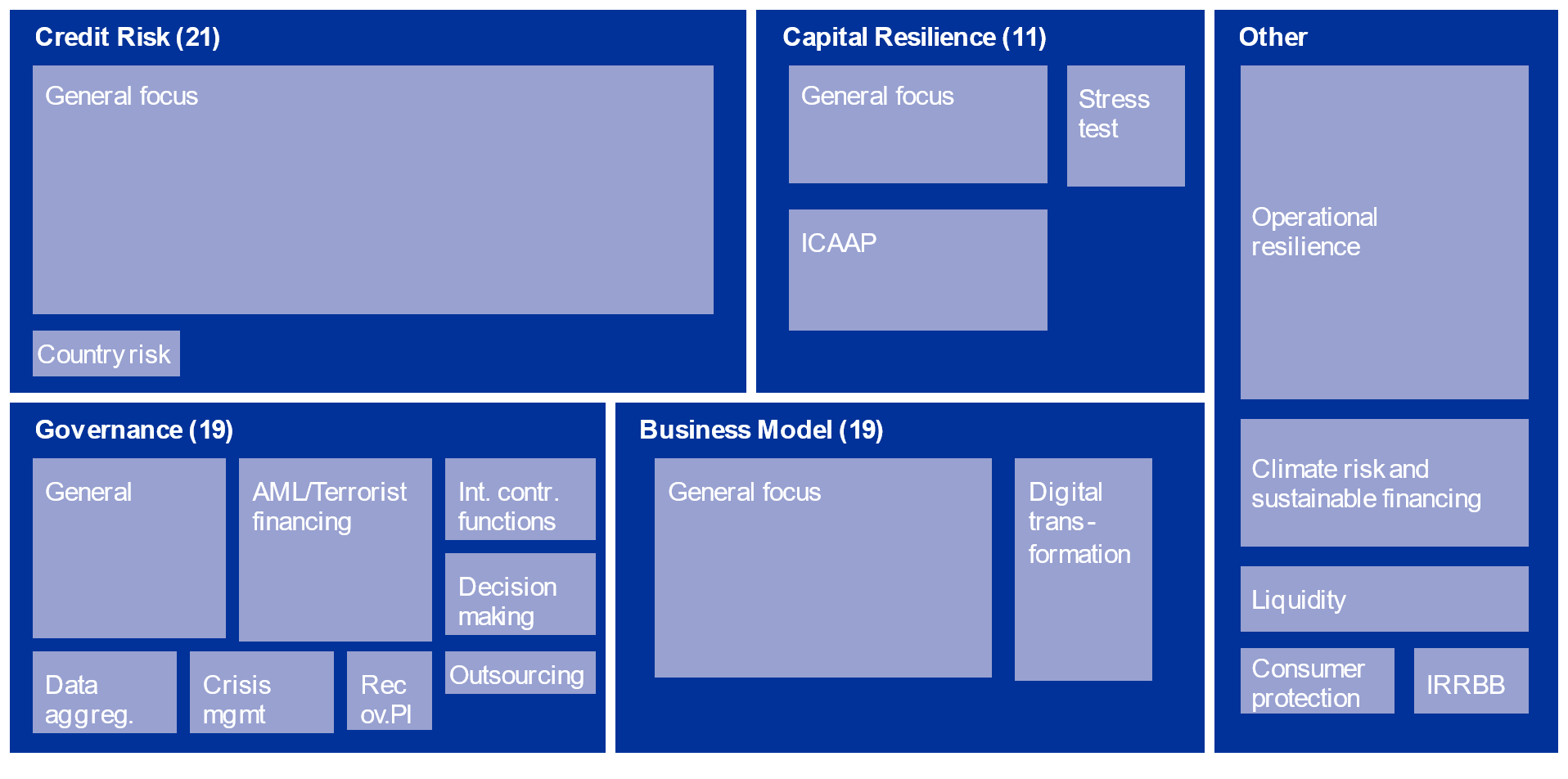

4.1 Overview of supervisory priorities

Overall balance sheet growth driven by loan business and increased cash positions…

Every year ECB Banking Supervision, together with the NCAs, performs a thorough assessment of the main risks and vulnerabilities faced by the significant institutions under its direct supervision and sets its strategic priorities for the next three years accordingly. These are reflected in the Banking Supervision Risks and Priorities 2022-2024. They are directly applicable to SIs, but also set the tone when NCAs lay down the priorities for supervision of LSIs in their jurisdiction, taking into account local specificities and proportionality. For 2021, ECB Banking Supervision focused on four priority areas materially affected by the pandemic, which were also largely reflected in NCAs’ priorities at national level: credit risk management, capital resilience, business model sustainability and governance. Idiosyncratic factors are considered at country level, resulting in specific focus topics. Another common characteristic in NCA priorities was operational resilience.

The key priorities from 2021 – credit risk, business model and governance – remained in place in 2022, with the addition of operational resilience.

The priorities identified by ECB Banking Supervision and the NCAs generally remained key also in 2022. In terms of NCAs’ focus in LSI supervision, the second most relevant priority after credit risk related to operational risk, predominantly cyber security and IT risk, which was already a key concern in 2021. Business models and governance both remained important for NCAs in 2022, with a wide range of specific focus aspects.

Figure 1

NCA LSI supervisory priorities for 2021

Source: Annual reports of NCAs.

Notes: Numbers next to priorities indicate how many NCAs have set priorities in this area. The sizes of boxes approximate prominence as declared by NCAs in their priorities; IRRBB = Interest rate risk in the banking book; Recov. PI = recovery plans.

4.2 Credit risk: much achieved, but pockets of work remain in a number of places, while risks are increasing again

For credit risk the main objective of ECB Banking Supervision in 2021 was to further strengthen the initiatives launched in 2020 to ensure banks have adequate risk management practices in place to identify, measure and mitigate the impact of credit risk, as well as the operational capacity to manage the expected increase in distressed borrowers. Given the relevance of credit risk in light of the pandemic, it also made monitoring the evolution and effective management of non-performing exposures (NPEs) and potential cliff effects from expiring moratoria a key priority for LSI supervision across all SSM jurisdictions. Compliance with the recently further harmonised definition of default, the adequacy of banks’ classification frameworks for UTP loans – and consequently NPEs – and proper IFRS classification were also subject to intensified supervisory focus in several countries. Several NCAs put an emphasis on assessing LSIs’ compliance with the new EBA Guidelines on loan origination and monitoring. In addition, risks related to climate change (but not limited to credit exposures) were deemed relevant by NCAs.

Over the last two years one of the main areas of oversight has been the assessment of risks and vulnerabilities which emerged during the coronavirus crisis, such as sectoral risk analysis, loans under moratoria and close monitoring of exposure classification in terms of UTP, forbearance or staging.

Despite multiple supervisory initiatives in recent years, which have already helped improve it, credit risk management remains a key area of attention.

Other initiatives undertaken in 2021 related to NCAs following up on supervisory expectations with regard to the identification, measurement and operational management of credit risk. These were communicated to LSIs on the basis of, and consistent with, those that ECB Banking Supervision had addressed to the chief executive officers (CEOs) of SIs, while duly reflecting proportionality considerations. In addition, NCAs supported activities in the area of credit risk by means of thematic reviews where credit risk was a key topic (38 thematic reviews were launched in 2021). 102 on-site inspections, predominantly focused on credit risk, were conducted.

A dedicated workshop was held at which the ECB and NCAs discussed benchmarking analyses of quantitative indicators of the impact of the pandemic on LSI’s credit risk exposures and management and exchanged views and experiences on dedicated supervisory initiatives. This covered various dimensions, ranging from stress testing to targeted on-site inspections, based on a series of case studies from NCAs’ recent activities. These collaborative efforts were being reinforced in 2022 with further quantitative and qualitative benchmarking of supervisory activities and practices.

Looking ahead, credit risk remains a highly relevant NCA key priority for LSI supervision, not only in terms of dealing with further impacts from the pandemic and first and second-round effects from the Russia-Ukraine conflict which might still materialise, but also more general aspects of managing credit risk. One aspect mentioned by several NCAs was the need to further assess banks’ compliance with the EBA Guidelines on loan origination and monitoring. Also prominently mentioned by NCAs as a focus area were risks related to climate change (which are not limited to credit exposures).

New key challenges that have emerged recently and hence were not fully captured in the priority setting process in 2021 relate to macroeconomic performance in light of geopolitical developments and inflation. These are expected to be prominently reflected in NCAs’ activities in the area of credit risk. The rapid escalation of tensions between Russia and Ukraine in 2022, culminating in the Russian invasion, represented an exogenous shock to the European economy and financial sector. LSIs took the initial impact of this shock from a sound prudential position overall, which has so far allowed the sector to cope with increased volatility and uncertainty without any major disruptions. The focus has now shifted to include the analysis of second-round effects from the war. These may materialise through trade channels, volatility in the commodity and energy markets, energy shortages, supply chain disruptions and a broader deterioration in the macroeconomic outlook. The severity of the impact for individual LSIs will depend on their exposure structure and business model.

LSI supervisors have been in close contact through a dedicated contact group which aims to ensure an efficient flow of information. This group helped identify those LSIs with the largest exposures and strongest institutional linkages to the conflict region. It has contributed to the convergence of supervisory approaches by sharing knowledge and identifying best practices, especially when dealing with idiosyncratic cases of a similar nature.

The ongoing war and its transmission into macroeconomic conditions continue to pose challenges. LSIs need to include the potential future impact on their balance sheet and capital adequacy, particularly from exposures to borrowers hit by the crisis, in their assessments. Prudent provisioning for credit risk losses and amendments to planned capital distributions should be considered as required by future developments, bearing in mind not only second but also third-round effects from inflationary pressures and the broader impact on trade.

4.3 Business models: more effort needed – banks are moving too slowly