- SPEECH

Basel III implementation: the last mile is always the hardest

Speech by Andrea Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the Marco Fanno Alumni online conference

Frankfurt am Main, 3 May 2021

Professor Barba Navaretti,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I am very grateful for the invitation to speak to you at this alumni meeting of the Associazione Marco Fanno. The Associazione has a long tradition of providing financial support for advanced studies in economics at internationally renowned universities. Since the 1960s numerous leading academics and policymakers in the field – many Italian, but not all – have benefited from the Associazione’s scholarships and previously existing affiliated schemes.

Rather predictably, my remarks tonight will focus on banking issues. More specifically, I would like to talk about international banking regulation. Later this year we expect the European Commission to issue the legislative proposals to implement the final package of the reforms agreed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS). This last step completes the policy response to the great financial crisis. The Governors and Heads of Supervision (GHOS) in turn have committed to refrain from launching major adjustments to the international standards for the foreseeable future.[1]

But the last lap of this long process is still facing fierce opposition from some in the banking industry who argue that the impact of the reforms might adversely affect banks’ capacity to support the recovery from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic shock. I am firmly convinced that a full and timely implementation of this last set of international standards is in the interest of all stakeholders. It requires only limited adjustments in the short term but will deliver the necessary structural improvements to our regulatory framework as well as sizeable and long-lasting benefits for our economies. Most importantly, I believe that the effectiveness of international standards, which is of great value to supervisory authorities and international banks alike, crucially relies on the commitment of all signatories to faithfully implement them in their domestic jurisdictions.

Before I go into the detail of the final stretch of this journey – the implementation of the final Basel III package – I would like to briefly look back on how the journey began and how banks’ internal models, which the package addresses, came to the fore of international discussions.

The BCBS was established in the mid-1970s after the collapse of the German bank Herstatt. Its creation reflected the awareness that, after three decades of financial stability (although some would perhaps say three decades of financial repression), the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates and the ensuing free-floating exchange rate system had given new momentum to the international banking business, and banking regulation and supervision needed to catch up.

As well documented by Charles Goodhart in his excellent book on the early years of the Basel Committee[2], the newly constituted Committee was initially more concerned about supervisory cooperation than standard setting. The Basel Committee’s first document of note was in fact the Basel Concordat. In the wake of the collapse of Herstatt, the Concordat sought to set out the respective responsibilities of what we refer to in supervisory jargon as the “home” and the “host” authorities of international banking groups, as well as their duties of cooperation. The Concordat was revised in the aftermath of other international banking crises, like that of Banco Ambrosiano, and remained for many years the main point of reference for the activities of the Committee, and its main focus was international supervisory cooperation.

The standard-setting drive came later, as it became clear that supervisory cooperation, which sought to avoid disruptive crises of international banking groups, and standard setting, which aimed to foster an international level playing field, were closely connected. Competing regulatory standards from different jurisdictions endangered the very possibility of global financial stability and, in the end, would threaten both the level playing field across regional markets (including the United States and Europe) and the feasibility of international supervisory cooperation.

That is why, to effectively fulfil their national mandates, the national competent authorities and the central banks of the most relevant banking jurisdictions in the world not only had to cooperate ex post – in the run-up or, worse, in the aftermath of the crisis of a specific bank – but they also had to cooperate ex ante, so to speak, to align the regulatory requirements of internationally active banks at the technical level. The firm commitment by all participants to transpose what had been agreed in Basel into legally binding legal acts in each national jurisdiction – or supranational in Europe’s case – coupled with the peer review of the existing legislative frameworks, completed the institutional set-up of this global standard-setting body and laid the foundations of its credibility and reputation vis-à-vis banks and other market participants at the global level.

Now, it is important to underscore that Basel regulatory cycles are very long policymaking processes that take many years to complete. The highly technical nature of the subject matter requires detailed discussions at the negotiating table, consultations with the industry, impact assessment exercises and appropriate transitional periods to be defined before the new rules can actually become fully applicable. This last point is crucial to avoid disrupting the macroeconomic cycle with sudden changes in the regulatory requirements which modify incentives, alter the functioning of banks’ business models and, ultimately, affect the allocation of financial resources to the real economy.

Let’s take the first Basel Capital Accord as our starting point. Negotiations on a global regulatory capital standard for banks had already started in the early 1980s in the aftermath of the Latin American debt crisis, but the Committee only reached an agreement in 1988, with an implementation date being set for the end of 1992. This was achieved in the European Union (or European Community, as it was at the time) in 1989 through a suite of Directives, including the Solvency Ratio Directive and the Second Banking Coordination Directive, which were then transposed into the legal frameworks of all Member States.[3] Compared with the later accords, Basel I was notable for its simplicity but also its very limited scope for risk sensitivity. It established a simple minimum capital requirement of 8% of own funds of variable quality (common equity could, in the end, be as low as 2% of risk-weighted assets) and a few coarse risk weights for specified asset classes divided into 0%, 20%, 50% and 100% risk buckets. One of the key trade-offs in prudential regulation – between the simplicity of the rules and their risk sensitivity – would soon take centre stage.

Two developments made supervisory authorities realise that these broad-brush requirements were fast becoming obsolete. First, exactly in the same years of the definition of the Accord banks’ internal risk management techniques started to become more sophisticated[4], so that the risk sensitivity of the regulatory framework was falling out of touch with best market practices for the internal allocation of economic capital. Second, research conducted by the Federal Reserve System showed that banks had managed to develop a number of practices, such as expanding off-balance sheet activities, like securitisation, or adjusting effective exposures to risk within the broad buckets defined by the first Accord, to increase their level of risk-taking without being captured by regulatory requirements.

The need to bring regulation closer to the real risks involved in certain activities and prevent regulatory arbitrage opened the door to the regulatory recognition of banks’ internal models. If it was possible to measure risk in a more granular fashion for risk management purposes, then the same method should be used to quantify regulatory capital, as it would make the regulatory framework more efficient and more incentive-compatible.

In this context, in 1996 a market risk amendment to the Basel I Accord was agreed. For the first time, banks could use internal risk models to calculate regulatory requirements for market risk (but not credit risk). With the second Basel Capital Accord (known as Basel II), which was agreed in 2004 to become applicable in 2007, the internal model approach was extended to the calculation of capital requirements for credit risk, counterparty credit risk and operational risk.[5] The use of internal models was embedded in prudential requirements to calculate risk-weighted exposure amounts, the denominator of the capital requirement ratio.

It is sometimes erroneously argued that this move towards the use of internal models in the calculation of capital requirements was at the origin of the great financial crisis. Some critics saw the reform as epitomising a broader policy shift towards deregulation of financial markets. For these critics, relying on banks’ own internally developed methodologies to calculate their regulatory requirements was like letting the fox guard the chicken coop.

In actual fact, some of the jurisdictions at the epicentre of the great financial crisis, such as the United States, had not yet allowed banks to use internal models. The Basel Committee’s “use test”, which required banks to use the same models for internal risk management purposes as for the calculation of regulatory requirements, was intended to foster reliance on best market practices. And the ease with which sophisticated international banks managed to circumvent the simpler regulatory requirements of Basel I had, in the end, left the international supervisory community with no credible alternative.

Yet, it would be equally misleading to overlook the weaknesses in banks’ internal models and their use for regulatory purposes that were highlighted during the crisis. The regulatory framework for market risk had to be amended in 2009 because of shortcomings in the ability of value at risk (VaR) models to capture default risk and migration risk, with stressed VaR requirements introduced as a result.

What’s more, the increase in the risk sensitivity of prudential requirements caused by the Basel II standards generally led to an unintended reduction of risk density, i.e. the average risk weight for the largest and internationally active banks, and to unwarranted variability in risk-weighted assets, meaning similar portfolios were carrying vastly different capital charges without apparent differences in the underlying risk.

As the risk density decreased, banks were able to carry out more business based on the same absolute amount of own funds, thus expanding their balance sheets. They increased their leverage while still complying with the risk-weighted capital requirements and, in some cases, even increased their regulatory ratios.

This is well documented in a 2014 report by the European Systemic Risk Board’s Advisory Scientific Committee. The report shows that in the run-up to the great financial crisis, the median risk-weighted capital ratio – so Tier 1 capital to risk weighted assets – remained almost stable at around 8%, whereas the leverage ratio fell by almost half. By 2008 the median leverage ratio of the 20 largest European banks had dropped to just over 3% (assets were 32 times capital) from a previous average of 6% (17 times), while median risk-weighted regulatory capital ratios remained essentially unchanged.

An even more striking finding from the report is the negative correlation between the risk-weighted Tier 1 capital ratio and the equity-to-assets ratio, another measure of leverage. In short, banks that were more capitalised on a risk-weighted basis also had a lower leverage ratio, something that in itself called for a careful investigation into the role of the risk-weighted assets framework, and internal models, in banking regulation.[6]

Other analyses[7] show that shortly before the great financial crisis, the average risk-weighted solvency ratio of the large international banks that entered resolution or needed government support was well above the minimum requirements and not statistically different from the average solvency ratio of the banks that did not experience a crisis. The Tier 1 capital ratios appeared uninformative about banks’ true default probabilities and, therefore, the actual risks on their balance sheets.

We all know the intrinsic limitations of risk measurement models and the implications of their use for regulatory purposes. Of course, it is as much a supervisory problem as it is a regulatory one. As a supervisor I have always been deeply interested in the risk sensitivity of capital requirements. Intellectually, it seems clear that riskier assets should attract higher capital charges than less risky ones. But the real issue, which is almost a philosophical question, is whether financial risk can be accurately measured. As you probably know, there are splendid pages by Keynes, among others, on the irreducible uncertainty of economic outcomes and the impossibility of measuring real risk through probabilistic calculations.[8] To make this fundamental problem more tractable, supervisory authorities need to be in a position to robustly challenge banks’ modelling choices and their conservatism.

Since the early stages of implementation of the Basel II framework, several analytical studies, first by the BCBS and then the European Banking Authority, have shed light on the magnitude and implications of the unwarranted variability in risk-weighted exposure amounts across banks and portfolios with seemingly comparable risk profiles. As opposed to the risk-driven variability, which is a desirable feature of any risk-sensitive framework, the unwarranted one is typically driven by differences in modelling practices, model error, model arbitrage and insufficiently prescriptive regulatory frameworks.

Such variability makes it more difficult to compare banks’ reported capital ratios, thus undermining the visibility of supervisors and investors over the banking sector, and ultimately effective supervision and market discipline. It quickly became apparent that the use of internal models to gauge the default probabilities of debtors was not entirely suitable for every kind of portfolio. In particular, it was not suitable for the so-called low-default portfolios, for example large corporates, whose historical default events are not sufficient to feed the data-hungry models and enable their proper calibration.

It would be a mistake to think that the Basel II standard-setter had not anticipated these potential problems. In fact, one of the requirements of the new agreement was a minimum floor based on the previous accord. It was supposed not to be possible for a bank adopting internal models to reduce the regulatory capital charges in aggregate below 80% of the capital charges deriving from the application of the Basel I Accord. But to our surprise (I was chairing the European Banking Authority at the time), we found that the way the competent authorities in Europe were actually enforcing this Basel I floor was quite diverse and, in the end, often more lenient and in some cases not Basel compliant. In a number of Member States, the implementation of the Basel I output floor was so lax that no bank was actually constrained by it. Therefore, it is not surprising that the introduction of a recalibrated output floor in the final Basel III package is having more impact on certain banks that so far have enjoyed greater leeway through benefiting from a reduction in risk-weighted asset densities.

An additional point worth mentioning is that the quest for greater risk sensitivity through increased reliance on banks’ internal models came at the cost of increased complexity of the regulatory framework. Compared with the 30 pages of the first Basel Capital Accord, the latest version of the Basel framework incorporating all the changes up to January 2021 runs at more than 1,600 pages.[9] But it is not only a matter of the page count, as it is apparent that in the last three decades there has been a mind-boggling increase in the complexity of the regulatory framework and the attendant legislative instruments. This has had an impact not only on the complexity of banking business, but also that of supervisory activities (for example supervision of internal models) and investors’ analysis.

For all the reasons I mentioned, and with the aim of restoring the credibility of the international standards and simplifying the framework somewhat, the Basel Committee engaged in a last lengthy and thorny round of negotiations to finalise its post-crisis standards on the calculation of risk-weighted assets, which is really the core of prudential banking regulation. And this is where the last mile of the title of my speech comes in – as we are now in the last mile of a long regulatory marathon stretching back more than 40 years.

The agreement reached in 2017, among other things, restricts the use of banks’ internal models across several dimensions. These restrictions include (i) removing loss given default modelling for low-default portfolios (namely banks and large corporates) and all credit risk modelling for equity portfolios; (ii) introducing several model input floors in the area of credit risk; and (iii) removing the use of internal models for operational risk and credit value adjustment risk. In addition, the agreement imposes a much-discussed output floor, that is the requirement that risk-weighted assets resulting from internal models cannot be less than 72.5% of the risk-weighted assets deriving from the standardised approach. It should also be noted that, to maintain an overall high level of risk sensitivity, the reform improves the granularity of several standardised approaches and reduces their reliance on external ratings.

This is now all close to implementation. When I say close to implementation, I am aware that it could still take a few years before the final touches to the international capital standards are actually fully in force, especially in Europe.

In fact, the date for implementation was first scheduled for January 2022 with an additional five years of transitional period, so a fully-fledged implementation only at the beginning of 2027 ‒ almost 20 years after the technical work began following the Lehman crisis. And, in the midst of all this, the COVID-19 pandemic struck. At the beginning of this exogenous crisis, the Basel Committee decided to push back the implementation date to the beginning of 2023[10] in order not to disrupt the business cycle even more. And this brings us at least to 2028 for the final deadline. Since in Europe there is still no legislative proposal from the European Commission, and the legislative process, for legislative initiatives of comparable complexity, takes on average between two and a half and four and a half years to conclude, we already risk missing the 2023 deadline for implementation, not to mention the ensuing transitional period, before the finish line is actually reached.

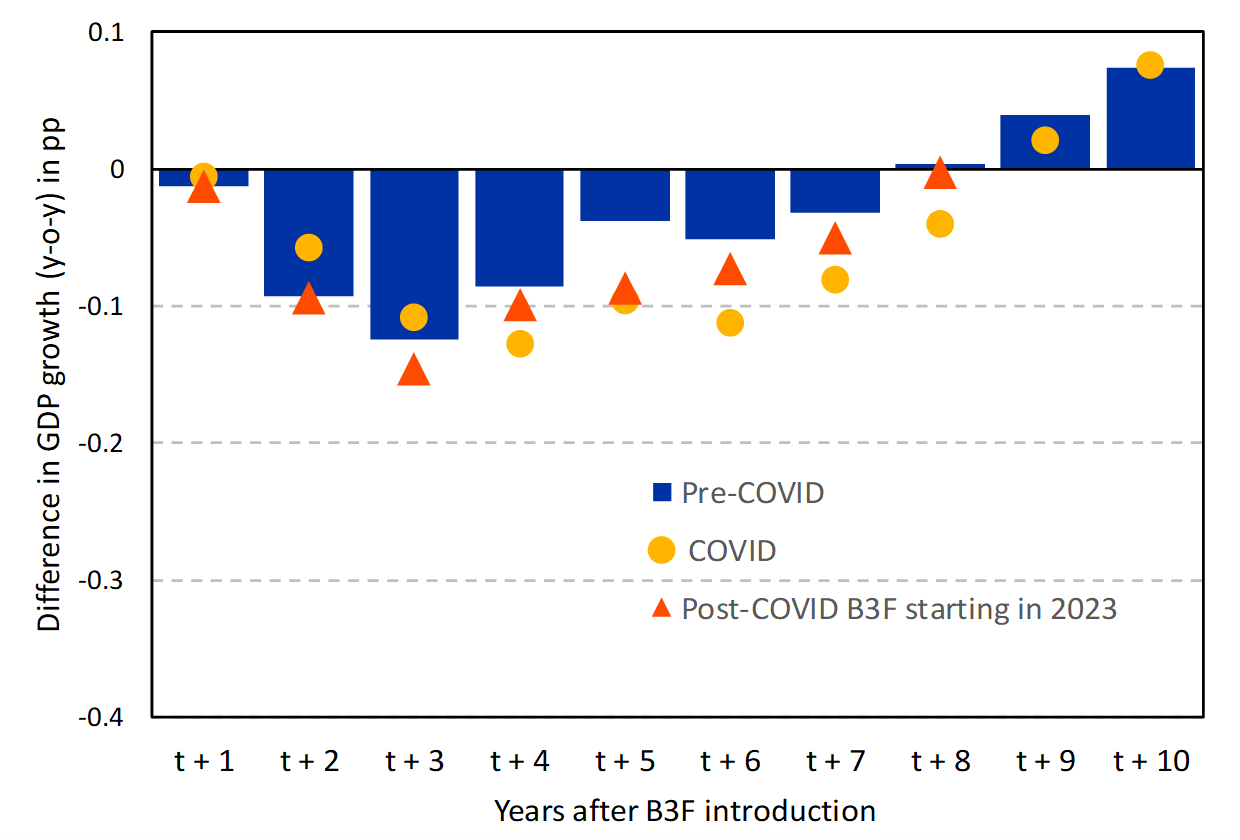

In this context, I am hearing calls for the initial date of implementation to be further postponed. Let me be very clear on this. We do not see any benefits in further delays. Our assessment of the macroeconomic impact of implementing the last leg of the Basel III reforms shows very small phase-in costs, only in the short run, and fully compensated by long-term resilience gains.

The additional one year of delay owing to the COVID-19 crisis has brought the short-term costs of the reform back to the levels we would have observed at the original implementation date in 2022 in the absence of the pandemic. Further delays would only stoke uncertainty and postpone without apparent benefits the necessary adjustments in the banking sector.[11]

Chart 1

The GDP costs of Basel III implementation

Sources: ECB staff calculations

Notes: The pre-COVID-19 simulation is based on the December 2019 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections and assumes the start of the Basel III reform at the end of 2019. The COVID-19 simulation is based on the June 2020 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections and assumes the start of the reform at the end of 2019. The post-COVID-19 simulation is based on the June 2020 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections and assumes the start of the reform at the end of 2022. Basel III stands for the Basel III framework.

It is important to emphasise that what we have actually seen from the unexpected COVID-19 crisis is precisely that a well-capitalised banking sector is an essential pre-condition for the effectiveness of public policies aimed at preventing excessive volatility of the macroeconomic cycle. As I have said on numerous occasions, the European banking sector entered the COVID-19 crisis in a much stronger position than in the past. The capital position was much stronger than at the beginning of the previous crisis: with 16% Tier 1 capital ratio in the last quarter of 2019 the euro area banking sector was at a level almost double than in 2008 and with capital of a much higher quality thanks to the comprehensive post-crisis reforms. Also, liquidity buffers were much stronger. We had, at the end of 2019, €3.4 trillion of high-quality liquid assets or liquidity buffers available for the banks supervised by the ECB, and an average liquidity coverage ratio of 146%. There is clearly no room for complacency, but we can take some comfort from the fact that the sweeping regulatory reforms of the past decade have brought the banking sector into a position where, overall, it is sufficiently resilient to tackle a shock of a magnitude never seen before in the European Union.

It is more apparent than ever that a more resilient and better capitalised banking sector, rather than acting as a drag on macroeconomic performance, is actually helping the real economy to perform better in good times as well as bad, hence smoothing the business cycle. An additional reason not to delay further the implementation of a long overdue reform.

Moreover, it is worth highlighting that unlike the previous chapters of the post-crisis reforms, the current package does not aim to raise the bar for all banks: the impact is now very diverse across banks according to their business model, size and degree of reliance on internal models. It is a structural reform, which aims to restore the credibility of internal models and the level playing field across banks. Postponing or watering down the Basel III standards in European implementation would only crystallise for a longer period of time an undue regulatory benefit for some banks at the expense of others, and with the risk that trust in internal models would completely evaporate in the event of further crises.

In this respect it is also worth mentioning that the regulatory package is the necessary complement to the very granular supervisory work conducted by the ECB with its targeted review of internal models (TRIM), completed only a couple of weeks ago.[12] As a follow-up to 200 on-site internal model investigations and with a clear definition of our supervisory expectations in a published Guide, we have asked banks using internal models to increase by €275 billion (around 12%) their risk-weighted assets with an additional capital absorption of 70 basis points of Common Equity Tier 1. I have already said that unwarranted risk weight variability is as much a regulatory as a supervisory problem, and it is obvious that our supervisory initiatives are leading in the same direction, thus significantly reducing the distance our banks need to cover in order to ultimately comply with the latest Basel III reforms. TRIM also confirmed the value of rigorous supervisory monitoring of the performance of internal models, of the correct application of the rulebook and of internal safeguards to ensure proper management of the models and adequate quality of the underlying data.

The last point I would like to make concerns the modalities of the implementation in the EU of the final Basel III Accord and, in particular, the thorny issue of the output floor. In the eyes of many members of the Basel Committee this is an indispensable element of the reform, in terms of guaranteeing a global level playing field which has always been, as we have seen at the beginning, one of the foremost objectives of the Committee.

I consider it of fundamental importance that the Union legislature, when implementing the output floor, does not give in to the temptation to introduce creative approaches. I am clearly referring to proposals like the parallel stack approach that, in the end, as already confirmed by the European Banking Authority,[13] are not actually in line with the internationally agreed standards but impair their very effectiveness and the comparability of capital ratios across banks and jurisdictions. There should be only one amount of risk-weighted assets for each individual bank and which takes into account the floor set down by the internationally agreed standard. A calculation of the risk-weighted assets of banks at variable geometry, so to speak, once with the floor and once without the floor, would only increase the complexity of the framework ‒ introducing additional confusion and stoking uncertainty for market participants.

I have already said, and I can reiterate this here now, that, as supervisors, we are ready to mitigate any unintended effects of an accurate implementation of the output floor. In particular, when setting our Pillar 2 capital requirements, we will avoid any double-counting of model risk and any sorts of unwarranted regulatory drag from the recalculation of risk weights linked to the floor. I can confirm that, if risk-weighted assets increase as an effect of applying the floor, we will not let Pillar 2 requirements to automatically rise in absolute value, in the absence of a corresponding increase in the underlying risks.[14]

I am convinced that this supervisory approach, together with the application of the output floor only at the consolidated level, will avoid an excessive increase of overall capital requirements (Pillar 1 and Pillar 2) also for individual banks. But it is of the utmost importance that the legislative implementation in the EU does not muddle the linearity of the agreement reached within the Basel Committee. It is also a reputational issue for the Union as a jurisdiction that respects in bona fide the consensus achieved within the global standard-setting body.

Conclusion

Ladies and Gentlemen, I have talked to you today about the long cycles of international banking regulation. I have probably taken a longer historical detour than I would have liked, but without that history it would be next to impossible to understand the complexity of the current framework.

We are now at a defining juncture where the quest for internationally agreed capital adequacy requirements for banks will soon be coming to an end. As already mentioned, the Governors and Heads of Supervision of the G20 clearly committed the BCBS to abstain from major regulatory changes in the Basel framework in the near future. There might be some adjustments at the margin, reflecting the assessment of the effectiveness of the reforms and their complexity, but I do not expect major regulatory overhauls.

When banks are complaining about regulatory fatigue, I can assure you that this fatigue is also shared by regulatory and supervisory authorities around the globe.

Now it is the time for implementation and application of this long-in-the-making international framework. We have reached the final mile of this endeavour, but it is precisely when the muscles are aching and the mind is not so clear any more that there is a risk of jeopardising all the efforts made before the final stretch. Let us cross the finish line together as soon as possible.

- See Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2020), “Governors and Heads of Supervision commit to ongoing coordinated approach to mitigate Covid-19 risks to the global banking system and endorse future direction of Basel Committee work”, press release, 30 November.

- Goodhart, C. (2011), The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision: A History of the Early Years 1974-1997, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- The Solvency Ratio Directive (89/647/EEC) and the Second Banking Coordination Directive (89/646/EEC) were, then, consolidated with the other banking directives in 2000 in the Banking Consolidation Directive (2000/12/EC) which was eventually repealed in 2006 by the first Capital Requirements Directive (2006/48/EC) which implemented the Basel II Accord.

- Andy Haldane of the Bank of England traces the origin of value at risk models to the aftermath of the Wall Street stock market crash of October 1987, with the American bank JP Morgan playing a significant role. See Haldane, A.G. (2009), “Why banks failed the stress test”, speech at the Marcus-Evans Conference on Stress-Testing, London, February, p. 2.

- Following the fundamental review of the trading book, internal models were also introduced for the calculation of capital requirements for credit valuation adjustment risk.

- See ESRB (2014), “Is Europe Overbanked?”, Reports of the Advisory Scientific Committee, No 4, June, p. 8.

- Haldane, A.G. (2012), “The dog and the frisbee”, speech at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s 366th economic policy symposium “The changing policy landscape”, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August, pp. 10-11.

- See, for instance, J.M. Keynes (1937), “The General Theory of Employment”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 51, No 2, pp. 209-223, in particular pp. 212-214: “But at any given time facts and expectations were assumed to be given in a definite and calculable form; and risks, of which, tho admitted, not much notice was taken, were supposed to be capable of an exact actuarial computation. The calculus of probability, tho mention of it was kept in the background, was supposed to be capable of reducing uncertainty to the same calculable status as that of certainty itself”. And later: “By ‘uncertain’ knowledge, let me explain, I do not mean merely to distinguish what is known from certain from what is only probable… The sense in which I am using the term is that in which the prospect of a European war is uncertain, or the price of copper and the rate of interest twenty years hence, or the obsolescence of a new invention… About these matters there is no scientific basis on which to form any calculable probability whatsoever. We simply do not know.”

- A complete consolidated version of the current Basel framework, also periodically updated, is available on the Bank for International Settlements’ website.

- See Basel Committee (2020), “Governors and Heads of Supervision announce deferral of Basel III implementation to increase operational capacity of banks and supervisors to respond to Covid-19”, press release, 27 March.

- See Budnik, K. et al. (2021), “The macroeconomic impact assessment of Basel III finalisation in Europe”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 14, ECB, forthcoming.

- See ECB (2021), “ECB’s large-scale review boosts reliability and comparability of banks’ internal models”, press release, 19 April.

- See European Banking Authority (2019), “Policy advice on the Basel III reforms: output floor”, 2 August.

- See Enria, A. (2019), “Basel III – Journey or destination?”, keynote speech at the European Commission's DG for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union conference on the implementation of Basel III, Brussels, 12 November.

Europos Centrinis Bankas

Komunikacijos generalinis direktoratas

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurtas prie Maino, Vokietija

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Leidžiama perspausdinti, jei nurodomas šaltinis.

Kontaktai žiniasklaidai