- SPEECH

Better safe than sorry: banking supervision in the wake of exogenous shocks

Keynote speech by Andrea Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the Austrian Financial Market Authority Supervisory Conference 2022

Vienna, 4 October 2022

I am delighted to be here today and would like to thank Helmut and the FMA for inviting me to participate in this flagship event. It is the first large, in-person conference I have attended since the beginning of the pandemic, and I am pleased to have resumed my visits to the capitals of the banking union to engage in face-to-face dialogue with banks and staff at the national competent authorities.

Today I will focus on the risk outlook for the euro area banking sector at this delicate juncture and on the approach taken by the ECB to ensure banks remain focused on risk management and on prudently monitoring the multi-faceted downside risks emanating from a fast-changing economic environment.

Banks’ first half results portray a strong euro area banking sector with a robust capital position, abundant liquidity buffers and relatively good profitability. Banks and analysts alike project into the near future the beneficial impact of rising interest rates on profits that we have observed in the last few quarters and consider this effect powerful enough to outweigh the adverse impact of a likely deterioration in asset quality, negative valuation effects on securities portfolios and increasing funding costs.

I sense that an increasingly optimistic attitude is spreading, which generates a certain reluctance on the part of banks to seriously engage in supervisory discussions on the downside risks underlying the macroeconomic and financial outlook.

I believe a root cause of this attitude lies in the warning we, along with other institutions and public bodies, issued at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when we expressed our concerns about a massive deterioration in asset quality. Our estimates of the possible increase in non-performing loans (NPLs) in hindsight proved, to say the least, overly pessimistic in the light of the faster than expected rebound of the economy. Hence, we might be suffering the same fate as the boy who cried wolf in Aesop’s Fables, and a tendency might be spreading among banks to dismiss their supervisors’ calls for prudence as unjustified conservatism. Worryingly, this is occurring at the same time as Russian invasion of Ukraine is developing into a persistent and fully fledged macroeconomic shock.

It is my belief that exogenous shocks to the economy and the banking sector require supervisors to exercise extreme caution and that, when facing events of this kind, in banking supervision or elsewhere, it is generally better to be safe than sorry.

Also, I believe the events of the last decade should lead both supervisors and banks to be humble regarding the predictive capacity of their models in a world subject to major structural shifts. Supervisory projections in 2020 undoubtedly underestimated the increased liquidity and efficiency of the secondary market for NPLs, which enabled banks to continue cleaning their balance sheets during the pandemic. Similarly, banks should now take care not to blindly project into the future the exceptionally low default rates we have experienced in the last two years when they estimate their capital trajectories in the face of a rapidly worsening economic outlook. A wise and balanced combination of all sources of evidence and expert judgement are warranted to prudently safeguard the safety and soundness of the banking sector.

Second, no two exogenous shocks are alike, which is why no specific monetary and fiscal support pattern can or should be taken for granted as we leave the pandemic shock behind us and look at the future economic impact of the war in Ukraine.

Given the different backgrounds and trajectories of these two shocks and the different role public support measures may end up playing in both, we cannot simply assume that euro area banks will find navigating the geopolitical shock as smooth as the recovery from the pandemic.

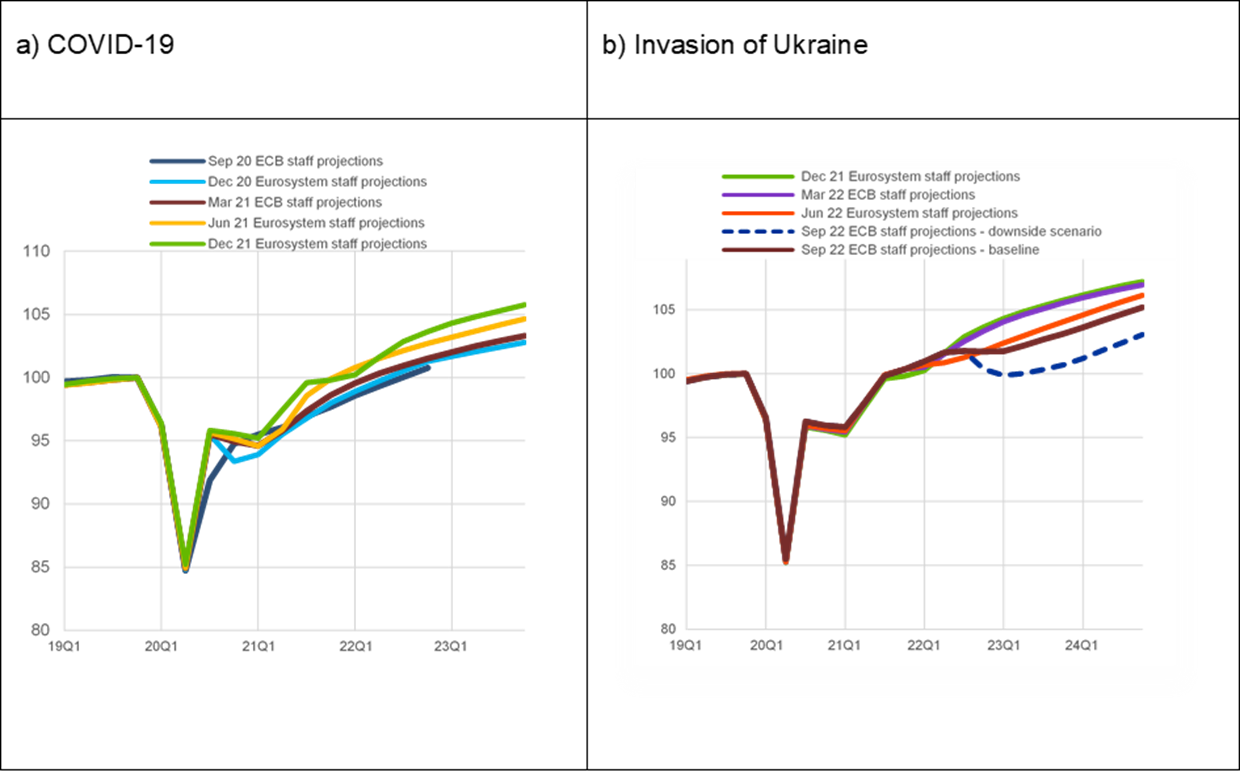

The macroeconomic impact of the COVID-19 shock was first fully modelled by Eurosystem staff in June 2020 as a deep and prolonged drop in euro area real gross domestic product (GDP) seen as unprecedented in peacetime (Chart 1, panel a). The shock was accompanied by historically high levels of uncertainty across several areas, including in forecasting, macroeconomics, finance and policymaking. As broad-based social restrictions were rolled out, the economy gradually came to a standstill and there was no sign of any possible near-term solutions. The economic environment in which this took place, as reflected in the December 2019 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, was characterised by near-term expectations of subdued but positive economic growth and inflation rates well below the 2% target. As European and national authorities began deploying unprecedented levels of broad-based monetary and fiscal support[1], subsequent baseline projections converged towards a sharp V-shaped recession and rebound. By the last quarter of 2021 real GDP had returned to its pre-pandemic level.

As I explained on other occasions, the extraordinary dynamics of the pandemic prompted the ECB to introduce two exceptional blanket measures: the recommendation to refrain from or limit dividends and the capital relief communication, aimed at promoting the usability of capital buffers. Historical data on the COVID-19 shock are now becoming available and, while we are relieved that our initial estimates for NPLs proved to be overestimated and no material levels of credit risk ultimately crystallised as a result of the pandemic, we see increasing evidence that we made the right choices, which, together with other public support measures, made a meaningful contribution to banking sector resilience. In two recently published analytical papers, ECB economists found that the capital relief measures adopted by ECB Banking Supervision during the pandemic were successful in supporting the credit supply and did not result in unwarranted risk-taking by banks.[2] They also found that the recommendation to refrain from or limit dividends was effective in mitigating the potential procyclical adjustments of banks.[3]

The geopolitical shock caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is developing into quite a different story. At the onset of the invasion in the first quarter of 2022, it was plausible to see it as a short-lived event which would put a strain on euro area banks’ limited and concentrated direct exposures to Russia and Ukraine. However, owing to the direct impact on energy, commodity and food prices of the rapid escalation of Western sanctions and retaliatory measures by Russia, the geopolitical crisis has turned into a macroeconomic shock, which is currently exacerbating the existing supply chain bottlenecks and accelerating inflationary pressures brought on by the pandemic.

Since the start of the conflict in Ukraine we have witnessed a gradual deterioration in the Eurosystem baseline and downside scenarios (Chart 1, panel b) accompanied by an acceleration in inflation rates and the normalisation of policy and market interest rates.

In their September 2022 projections, ECB staff forecast that in a downside scenario entailing a complete cut-off of Russian gas as well as oil flows into the euro area with no access to alternative gas sources, higher commodity prices, weaker trade, a deterioration in financing conditions and elevated uncertainty, GDP growth could be markedly negative (-0.9%) in 2023. The macroeconomic context is changing very quickly. Last week, the ECB President explained that negative growth was now the likely outcome for the last quarter of this year and the first quarter of next year.

Against this background, while it remains unclear what the impact of the shock might be on specific sectors of the economy, households and the financial sector, the likelihood of broad-based extraordinary monetary and fiscal support measures seems significantly lower than during the pandemic. The ECB has expressly stated that it expects to further raise interest rates in the coming months to dampen demand and counteract the risk of upward shifts in inflation expectations.[4] At this point, fiscal policy may have to be targeted towards the most vulnerable segments of the economy and preserve price signals. Both the ECB and the IMF have called on fiscal authorities to avoid introducing large and untargeted support schemes that could work at cross purposes to monetary policy.[5]

Chart 1

Exogenous shocks

Source: ECB/Eurosystem macroeconomic projections.

The situation we are facing today is therefore quite different from the one we faced during the pandemic, and expectations about forthcoming government actions should not be reflected in balance sheet management strategies. This also has implications when assessing the risk outlook for the euro area banking sector.

Euro area banks generally performed well in the first half of the year, reflecting a sector that is resilient and relatively profitable and which benefited from the post-pandemic economic rebound and normalisation of market interest rates. Later this week we will publish aggregate second quarter banking statistics covering all significant banks under our supervision. The data will confirm resilient capital and liquidity levels very close to the highs seen in the first quarter of the year, with the average Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio around 15% and the average liquidity coverage ratio well above 160%. The aggregate NPL ratio, which stood at 2% in the first quarter of this year, has continued falling, while the aggregate return on equity, which stood at 6% in the first quarter, has reached over 7%.

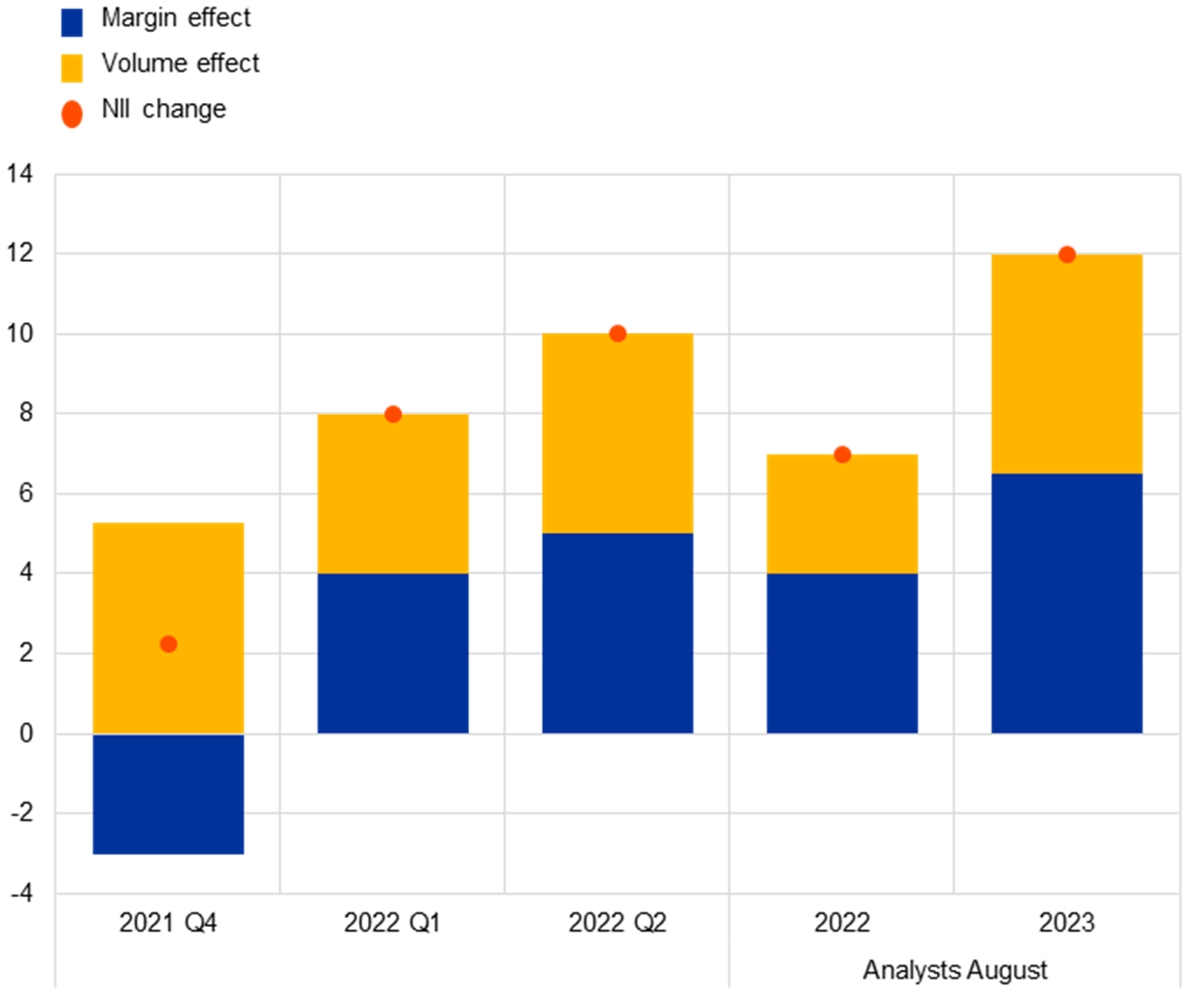

Net interest income continued its upward trend in the second quarter of 2022. The results of listed banks (Chart 2) show that this rise was driven by higher lending in the economy and by increasing interest margins, which continued to recover after narrowing during the pandemic. Initial indications suggest the second quarter increase in net interest income is broad-based, as it is reported by over 75% of the sample of significant banks under our direct supervision. It is also the highest increase of recent years.

Against a backdrop of no material levels of crystallised credit risk and material overlays of provisions built up during the pandemic, after a short-lived increase in the first quarter of 2022, the average cost of risk reverted to a downwards trend in the second quarter, generally returning to pre-pandemic levels.

When I speak to bank industry representatives and read market analysis, I detect widespread expectations that the interest rate normalisation bonanza will continue in 2023, with further increases in net interest income and further decreases in cost of risk. In general, this is expected to support stable if not higher levels of return on equity (Chart 2).

Chart 2

Net interest income quarterly change, listed banks

Source: Compiled from Refinitiv data.

Note: The sample comprises 38 listed banks.

The macroeconomic developments I have described require looking cautiously beyond headline NPL ratios and at additional metrics for credit risk evolution as well as across portfolios, business lines and business models. This will allow us to assess which specific vulnerabilities might materialise in the light of soaring energy prices, potentially more frequent and larger interest rate hikes than currently expected by the market and a looming recession. Let me elaborate on some of these aspects.

Non-performing loan volumes decreased across virtually all portfolios in the first half of this year but have recently started to increase in the consumer lending segment. In view of consumer lending’s negative sensitivity to rising interest rates, and given that consumer lenders are among the few banks that saw their net interest income fall in the first half of this year, the dynamics of this portfolio warrant particular attention.

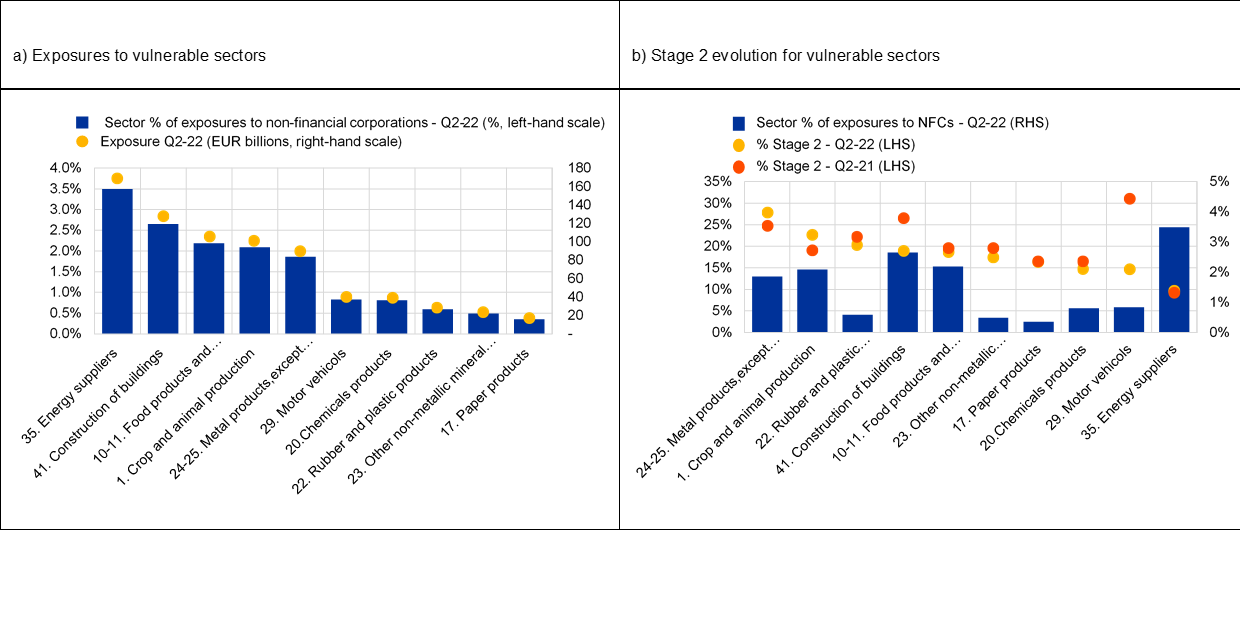

Underperforming loans, or stage 2 loans in accounting terms, continued to increase in the second quarter of 2022 to almost 10%, above the peak reached in the last quarter of 2020. This could indicate the build-up of heightened credit risk. As NPL volumes have fallen mostly due to sales, securitisations and write-offs rather than loan cures and repayments, higher stage 2 loan inflows might signal increasing NPL volumes in the near term once extraordinary NPL transfer operations slow down. The evolution of stage 2 loans needs to be monitored, particularly in relation to banks and bank business models exposed to sectors vulnerable to gas and energy price increases. Based on AnaCredit[6] data, which provides granular but incomplete coverage of bank loans in the euro area, exposures to these sectors may represent at least 18% of the non-financial corporate portfolio (Chart 3, panel a).

Chart 3

Euro area bank exposures to vulnerable sectors

Source: AnaCredit.

Note: The sample comprises credit institutions reporting the selected data points to AnaCredit as at June 2022.

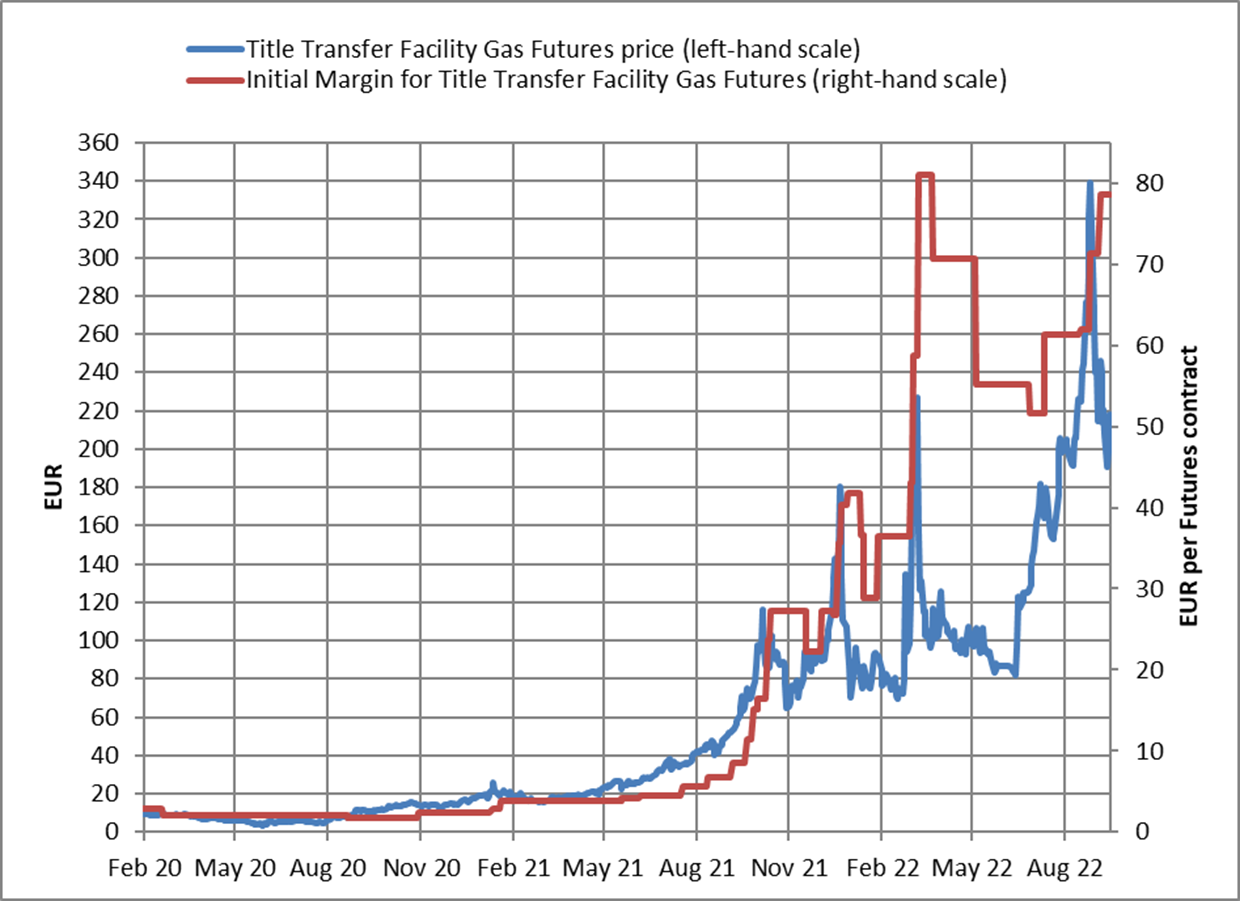

Some energy suppliers and energy-related commodity traders have been experiencing sudden and highly material liquidity shortages owing to very high and volatile margining requirements for clearing energy-related derivatives (Chart 4). The downside risks of energy price inflation and gas rationing may spill over further to some banks depending on how much additional liquidity support banks that are clearing members of energy derivatives decide to extend to these types of customers. I would caution against the idea, currently debated, of relaxing the existing margining requirements, as the latter were designed to protect the system precisely in times of stress. Also, more pervasive and widespread financial market volatility may spill over to other non-bank financial entities, exposing banks active in capital market financing to heightened market, liquidity and counterparty credit risk exposures.

Chart 4

Gas price and margins

Sources: ICE Futures Europe, ICE Clear Europe.

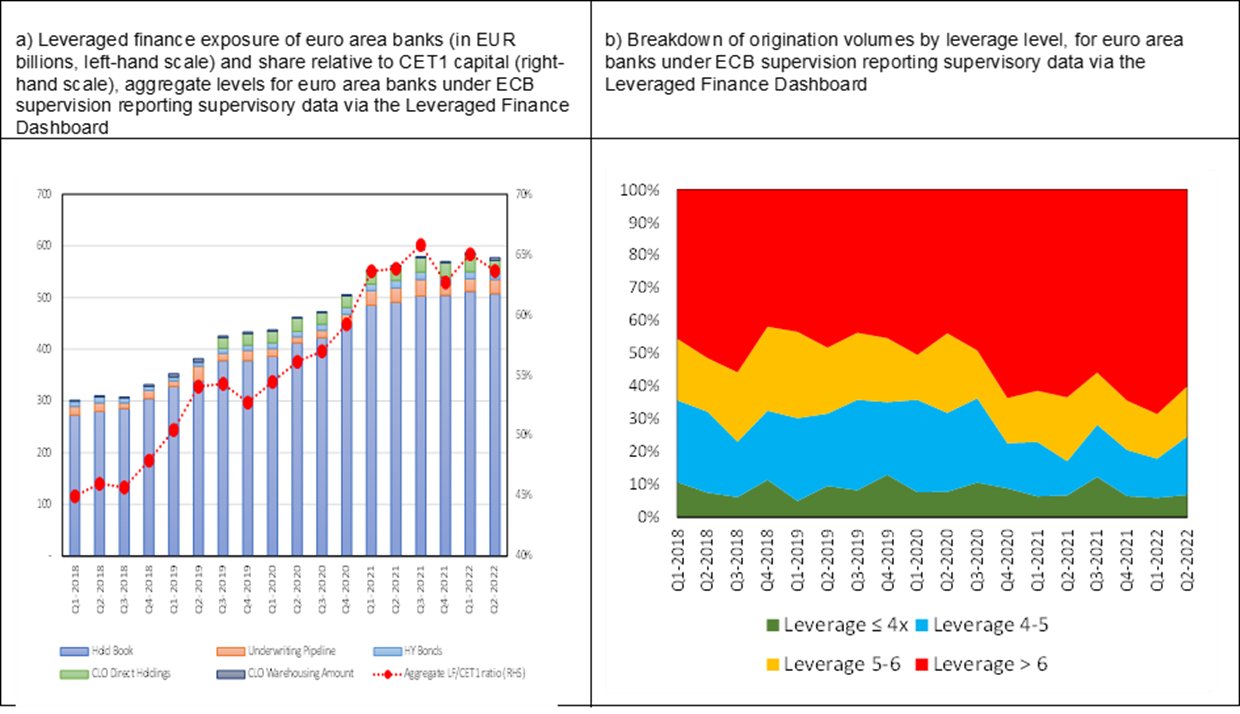

An additional pocket of vulnerability lies in the leveraged finance business. At an aggregate level, leveraged finance exposures, mainly in the form of leveraged loans, account for a sizeable share of euro area banks’ capital (Chart 5, panel a). Importantly, a large share of these exposures is to highly leveraged corporates, which are the riskiest segment of an already high-risk asset class. This is the result of the sustained origination of riskier loans of this kind over the course of the last few years (Chart 5, panel b). Moreover, in the second quarter of 2022 we observed that the more active originators continued to underwrite new transactions almost as though it were business as usual, even though the opportunities to syndicate them were unclear. As a result, their underwriting pipeline exposures increased as inventories could not be sold because primary markets had closed down.

Chart 5

Leveraged finance developments in the banking union

Source: ICE Futures Europe, ICE Clear Europe

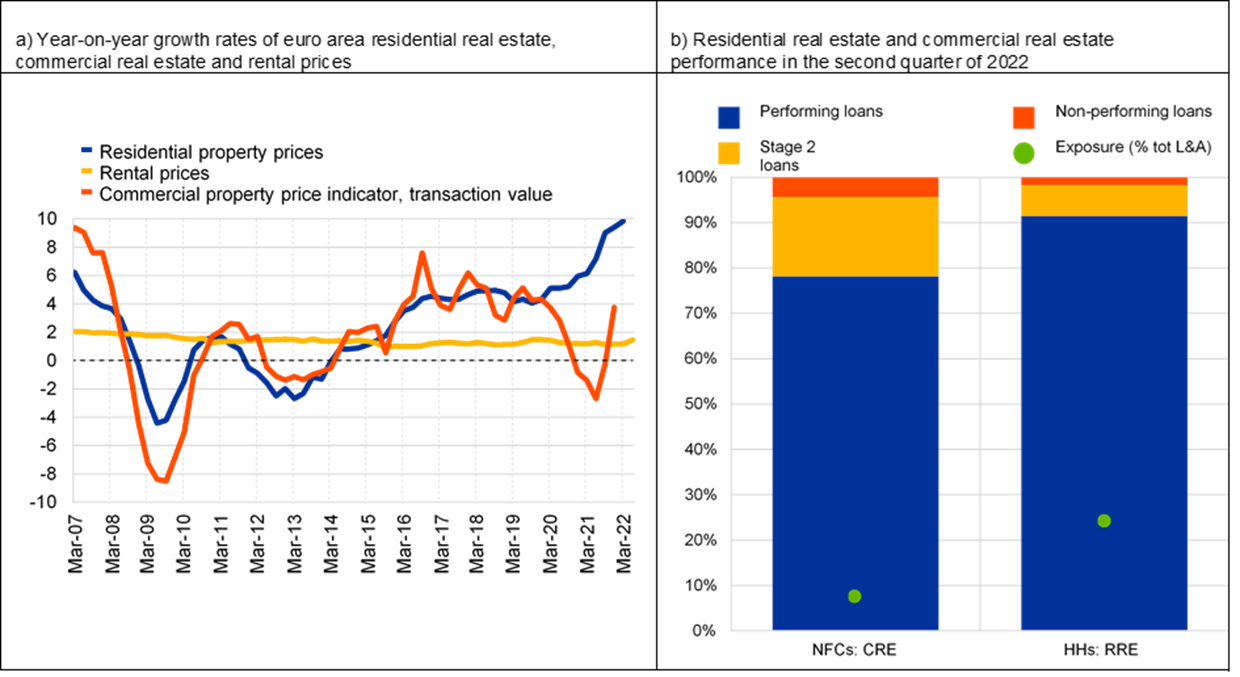

Large and rapid increases in interest rates coupled with the prospect of low or negative growth and inflation driving up consumption and investment costs might make it more difficult for some mortgage borrowers to service debt, particularly in those euro area markets where a significant proportion of residential mortgage loans have been granted at variable interest rates. Unlike in the commercial real estate market, where credit risk was elevated at the height of the pandemic, resulting in a large share of stage 2 loans (Chart 6, panel b), and prices have recently started to recover (Chart 6, panel a), the residential market has been characterised by a steady build-up of risk fuelled by a prolonged period of very low borrowing costs and increasing value of residential collateral (Chart 6, panel a).

Chart 6

Euro area real estate developments

Source: ECB and Supervisory Reporting

Lastly, let me mention that it will be increasingly important to monitor the potential impact of interest rate increases on banks’ balance sheets. This is not only in view of the potential impact of credit risk and asset quality deterioration, which could overturn the net beneficial impact that interest rate increases on average have on bank profitability, but also because of potential asset-liability mismatches resulting from ill-advised strategies by some banks. In particular, as monetary policy withdraws its extraordinary support measures and banks’ funding costs increase in line with market rates, institutions that have long benefited from carry trade strategies, focused for instance on long-term sovereign debt, might see their profitability rapidly eroded.

The geopolitical crisis we are going through, unlike the COVID-19 pandemic, will probably have different effects across banks depending on how this particular combination of risks affects their business model and balance sheet structures. As it became clear that banks’ individual financial projections submitted last spring were rapidly becoming outdated, we asked banks to produce and submit updated individual capital trajectories, taking into account adverse macroeconomic scenarios broadly aligned with the downside recessionary projections of the ECB and incorporating a likely embargo on natural gas from Russia.

We are now waiting to collect the data requested, which will shed light on how banks expect to be affected by the crisis based on their specific circumstances and balance sheet conditions. In the meantime, we are working hard to assess and better understand, on a bank-by-bank basis through our supervisory teams, how the different sources of vulnerability I mentioned today, and a few others, are playing out and how they should be reflected in the supervisory assessment of banks. Some of our analyses are more advanced than others or have already borne fruit, such as in the areas of commercial real estate and leveraged finance, where we are deploying supervisory capacity we put in place in the wake of the pandemic. As I have stressed on previous occasions, these priorities remain fully valid in the light of the current geopolitical shock. Later this year and early next year I will report on the results of our work on counterparty credit risk management, banks’ risk management of interest rate and credit spread shocks, as well as the results of our sectoral analyses in energy-intensive sectors and residential real estate.

Conclusion

All indicators of the health and resilience of the banking sector paint a positive picture at present. The regulatory reforms enacted after the great financial crisis, the supervisory efforts made since the start of the banking union and in the wake of the pandemic, and the improvements in banks’ own risk management practices are an important bulwark enabling banks to withstand shocks much better than in the past. However, we are facing a particular configuration of risks, combining the effects unleashed by the war of aggression in Ukraine on energy and food markets, the disruption in supply chains and the pressure on demand from the reopening of those sectors most affected by the pandemic. Together, these factors are fuelling the current episode of persistent extraordinarily high inflation – with a faster than expected increase in interest rates and a significant increase in volatility in financial markets – in an environment of historically high levels of indebtedness of governments, corporates and households. This challenging outlook last week led the European Systemic Risk Board to issue an unprecedented warning, highlighting the risks to financial stability in the EU. So far, the favourable interest rate environment has played out well for banks but they need to remain alert to developments in the risk outlook, proactive in the early recognition and management of credit risk, and aware of possible pitfalls in the estimates provided by their own internal models in this particular risk environment. The ECB will continue with its focused efforts to promote prudent behaviour and the proactive management of risks, thus ensuring that our banks remain resilient and continue supporting the real economy during challenging times.

Thank you very much for your attention.

According to the European Fiscal Monitor (January 2022), the total size of the fiscal measures amounted to 5% of GDP in 2020 and 4% in 2021 and is projected to reach 1% in 2022.

Couaillier, C. et al. (2022), How to release capital requirements during a pandemic? Evidence from euro area banks, ECB Working Paper No. 2720, September. The authors. also found also found that, while capital requirement releases supported lending, allowing banks to operate below the Pillar 2 guidance had no significant impact on banks’ lending behaviour. Furthermore, banks appear reluctant to draw on their “in place” capital buffers, implying that the positive effect of capital relief on lending is stronger for those banks with an ex ante smaller capital space. This suggests a case for having more releasable buffers.

Dautovic, E. et al. (2021), Evaluating the benefits of euro area dividend distribution recommendations on lending and provisioning, ECB Macroprudential Bulletin, June. Banks that did not distribute previously planned dividends increased their lending by around 2.4% and their provisions by approximately 5.5%, and the recommendations appear to have mitigated the procyclical behaviour of banks closer to the threshold for automatic restrictions on distributions.

Lagarde, C. (2022), speech at the Hearing of the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs of the European Parliament, September.

Lagarde, C., ibid.

AnaCredit, short for analytical credit datasets, provides granular credit data that was not available before the great financial crisis. It makes it possible to identify, aggregate and compare credit exposures and to detect associated risks on a loan-by-loan basis.

Den Europæiske Centralbank

Generaldirektoratet Kommunikation

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Tyskland

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Eftertryk tilladt med kildeangivelse.

Pressekontakt