- SPEECH

A new stage for European banking supervision

Keynote speech by Andrea Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, 22nd Handelsblatt Annual Conference on Banking Supervision

Frankfurt am Main, 28 March 2023

Jump to the transcript of the questions and answersIt’s a great pleasure to be with you here once again for the Handelsblatt Annual Conference on Banking Supervision.

Following recent market turmoil the debate on banking regulation and supervision has again hit the headlines. I am sure Yasmin Osman will raise questions on this topic in our conversation later on, but I would like to say upfront that restarting the debate on regulatory reforms would not be productive. With the implementation of the Basel Committee’s final package, which once again I hope will be as faithful to the international standards as possible in all G20 jurisdictions, we have all the tools we need. The focus of our debate should be much more on effective supervision.

In this vein, today I want to explain how European banking supervision has developed and matured since its start-up phase. Through this development, the way we conduct supervision has been moving from one that is predominantly rules-based and heavily codified, to one that is more risk-focused and adaptable to rapidly changing economic circumstances. We are increasingly concentrating our supervisory resources on the risks that are most material. And as this implies increased discretion for our supervisory teams, we are also implementing more rigorous internal controls and more transparency and accountability towards our stakeholders. Our style of supervision has sometimes been criticised as excessively heavy handed and conservative. I believe we should aim at enhancing our efficiency, also with an eye on the compliance burden we impose on our banks, while in no way lowering our guard and actually strengthening our monitoring of risks and risk controls at the banks we supervise.

The early years of European banking supervision

European banking supervision has been operational for nearly ten years now. In that time, we have grown and developed. In human development, it is recognised that what makes you who you are is a mix of nature and nurture. I like to think the same is true for European banking supervision. Like any child approaching double digits, we have become the character we are through a combination of our institutional DNA and the experience we have had in the environment we’ve grown up in.

The European Union has been called a form of “regulatory governance” and it is in the DNA of the ECB as an EU institution to codify its practices into detailed rules, manuals, guidelines and regulations. This process of codification was crucial for our early years. At its launch, the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) was composed of the ECB and national competent authorities (NCAs) from 19 different Member States, each with its own processes, culture and practices. Establishing a consistent supervisory process towards the significant banks in the jurisdictions over which the ECB had assumed supervisory responsibility was a top priority. Codifying our supervisory practices – sometimes into long and detailed internal manuals – was how we overcame our initial national differences, to create a common culture and support the level playing field for European banks.

I am convinced this process of codification was the right way to go, and critical to the success of the first steps – I am tempted to say giant leaps – that we took in our early days.

Let me mention three main areas of work that strongly shaped, in my view, the level playing field delivered by the SSM.

The comprehensive assessment that we conducted at the beginning of the SSM enhanced the transparency of the balance sheets of significant banks and helped to rebuild investor confidence prior to the ECB assuming its supervisory tasks in November 2014. The outcome was transparent and credible, boosting the European banking sector. Banks strengthened their balance sheets. We took over supervision making sure that we had clear sight of significant institutions’ asset quality and that any capital shortfalls were addressed.

We brought significant supervisory pressure to bear on reducing non-performing loans (NPLs) – a huge legacy problem in the banking system when we took over supervision. NPLs are now a fraction of what they were. The volume of NPLs held by significant banks dropped from around €1 trillion to under €340 billion by the end of December 2022, the lowest level since supervisory data on significant banks were first published in 2015.

And we took action to ensure that European banks’ use of internal models can be relied upon and unwarranted variability in risk-weighted assets is reduced. The targeted review of internal models, launched by the ECB at the beginning of 2016, was the largest project conducted by ECB Banking Supervision in coordination with NCAs to date. This contributed to a level playing field in European banking by ensuring internal models are reliable and their outcomes are comparable. Through this, we ensured that supervisory practices are applied consistently across the euro area.

Achieving these steps forward required hundreds of supervisors working together across a whole continent, an exercise in supranational regulatory governance on a scale never attempted before. None of this would have been possible without a granular set of instructions to ensure that the work was carried out in a consistent way across all of the institutions participating.

Thus, codification is part of our DNA and has been essential to establishing a level playing field through these achievements. But, equally, our adaptation to the changing external environment has also shaped our development. Let me give you some examples.

In the pandemic, we had to rapidly adapt to the unfolding events, prioritising certain aspects of our supervisory work and deprioritising others. We paused the standard supervisory review and evaluation process (SREP), adopting what we labelled a “pragmatic SREP”. We showed our flexibility by adjusting timetables, processes and deadlines to take into account the radically changed working circumstances of both supervisors and bank staff. Faced with unprecedented levels of macroeconomic uncertainty, which made the risk levels very difficult to model and ascertain, we geared all our efforts towards banks’ risk control systems, their capital planning capabilities and their distribution plans.

More recently, the Russian invasion of Ukraine brought to the fore geopolitical risk, which compelled us to focus on the banks’ exposures to Russian counterparties, reputational risk associated with sanctions, the increased prominence of cybersecurity concerns and the risks triggered by an energy price shock. Here again, we needed to adapt by refocusing our supervisory resources towards sectoral analyses and very granular credit risk assessments, while gearing up our cyber risk toolkit. As I announced earlier this month, we are preparing our first cyber risk stress test for next year.

The fast-paced normalisation of the monetary policy environment has in turn required us to brush up supervisory tools aimed at tackling risks of the banking business that had long not been included among the priorities. I am thinking of interest rate risk in the banking book and funding and liquidity risk.

It’s inevitable that these experiences of responding to external shocks, needing to reprioritise in the face of rapid changes in the macro-financial outlook, and high uncertainty has conditioned our character as a supervisory framework. And looking ahead, two underlying structural trends of our economies and banking systems, namely the digital transformation and climate change, require the banking supervisor to develop new supervisory policies and build up new expertise.

I want to explain now the measures we are taking to consolidate this experience, entrenched flexibility and risk focus into our supervisory approach and prepare for the challenges ahead, by becoming more efficient and more impactful in our actions.

Before I do so, let me say first that these changes are not about asking banks to have any more or less capital. It is important I make this clear because there are some views I have heard recently in my discussions with banks and analysts that I would like to dispel.

The first is the belief that, in Europe, we are more burdensome with regards to our capital requirements than in other jurisdictions.

It is true that in the United States, authorities took a decision to decouple the rules applicable for the large systemically important banks from those for medium-sized and smaller banks, expanding in 2018 the scope of banks benefiting from lighter regulatory approaches. In the European Union, we traditionally implement the Basel standards more consistently across banks of all sizes.

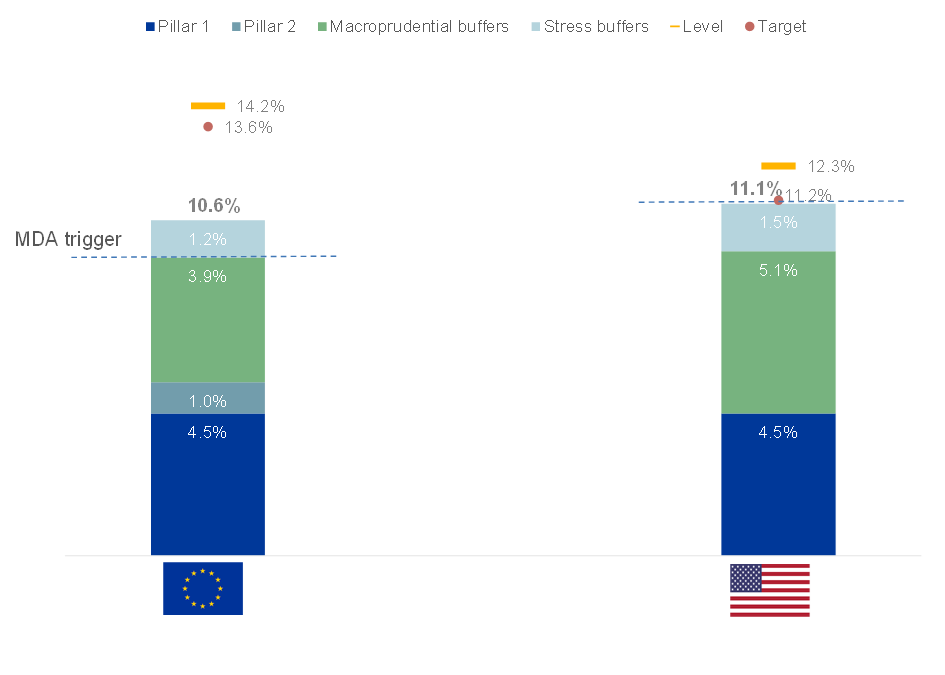

However, that does not hold for the G-SIBs, the global systemically important banks, which are more comparable in terms of business model and which compete on global markets. EU G-SIBs are in the same ballpark as US G-SIBs in terms of capital requirements: the weighted average Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital requirements for EU G-SIBs stood at 10.6% as at the fourth quarter of 2022. For the US G-SIBs, the CET1 capital requirements were a little higher at 11.1%. But I don’t want to make too much of simple comparisons – there are many differences in the types of risks that banks run, and we know for example that the risk weights attached to European banks’ assets tend to be lower than those applied in the United States.

CET1 capital levels and requirements, comparison between EU and US G-SIBs*

Weighted averages, reference period Q4 2022

Source: Regulatory reporting and public quarterly reports for the United States. (Comparison might be affected by different reporting and accounting standards.)

Notes: * For EU: Stress buffer = Pillar 2 guidance. Macroprudential buffer = 2.5% + Countercyclical buffer + max(G-SIIB,O-SIIB)+ systemic risk buffer. For the United States: Stress buffer = Stress capital buffer - 2.5%, Macroprudential buffer = 2.5% + G-SIIB. MDA stands for maximum distributable amount.

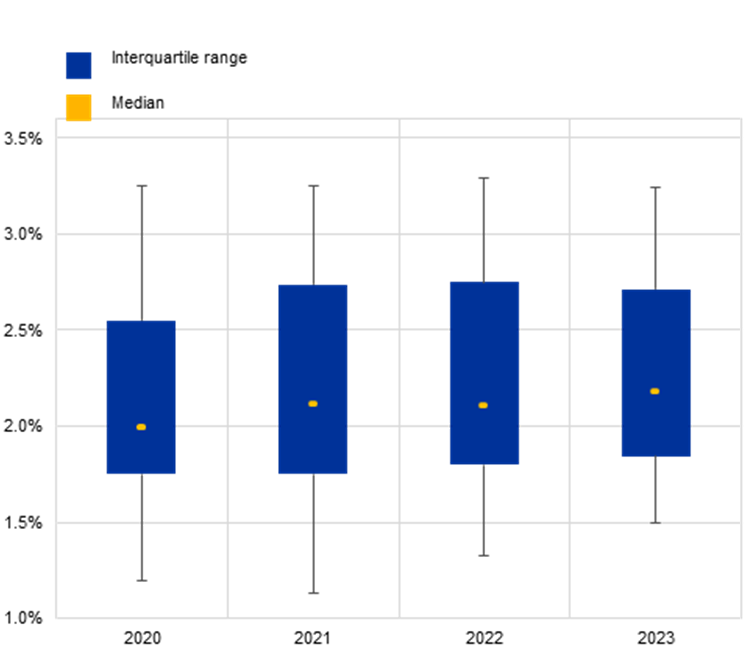

Second, some stakeholders maintain that we are constantly raising the capital bar by increasing Pillar 2 requirements. In fact, the average P2R has been remarkably stable on a year-on-year basis.[1] This is despite the fact that the risks that it captures have partly changed as we adapted our methodologies to the changing risk environment, to specific microprudential concerns and to the individual circumstances of our banks. For instance, elements of volatility in the P2Rs applicable in 2023 stem from add-ons addressing the insufficient risk coverage of non-performing exposures and the excessive exposure to the risks associated with the leveraged finance business. These ad-hoc supervisory treatments are temporary in nature and will be unwound as banks take measures to adhere to the corresponding guidance.

Distribution of Pillar 2 requirements in total capital

Sources: Sample selection follows the Supervisory Banking Statistics (SBS) methodological note for Q1 2020 (SBS sample based on 112 entities), Q1 2021 (SBS sample based on 114 entities), Q1 2022 (SBS sample based on 112 entities). For Q1 2023, the sample is based on the latest available list of supervised institutions (110).

Notes: Chart displays P2Rs according to their year of applicability (i.e. 2023 includes P2Rs decided in the SREP 2022 and applicable in 2023).

Third, there is a perception that we are in some way increasing capital requirements by the back door through our internal model investigations leading to increased risk-weighted assets (RWAs) and that, in doing so, we are making capital requirements an unpredictable variable. In reality, there is no policy aimed at making internal models more costly and no intention to surprise banks with tighter requirements. Most of the impact of our work on internal models was accomplished through the targeted review of internal models, the final report on which was published in 2021. The overwhelming majority of internal model inspections that we have carried out since 2020, for instance in the area of credit risk, follow from requests submitted by banks for material model changes to be made in the context of the European Banking Authority (EBA) internal ratings-based repair programme, which the EBA started planning and communicating back in 2016. Under that programme, model changes can result in increased RWAs in those cases where the bank’s model specifications differed, to a material extent, from the requirements specified by the EBA. On an ongoing basis, we are required by law to only grant banks permission to use internal models if they meet the relevant requirements. With the implementation of the finalised Basel III reforms, which notably constrain the use of internal models under several dimensions, we should expect a slowdown in such supervisory activity. It is also up to banks to reduce the complexity of their internal model framework in those instances where, rather than achieving true risk sensitivity of capital requirements on material business lines, models are only used to achieve even very minor regulatory capital savings on non-core business.

But this is not about capital – it’s about supervision. Let me now explain the initiatives under way that will contribute to a more risk-based and transparent banking supervision.

Towards a more risk-focused and transparent supervisory approach

We want to embed agility and the risk-focused approach in our supervision for the long term.

To do this, we have decided to introduce a new, supervisory risk tolerance framework, which is designed to enable supervisors to better adjust to bank-specific needs. Under the new framework, supervisors will be able to devote more time to address our strategic priorities and those vulnerabilities that are key for a specific bank, focusing their efforts where they are most needed. To make this possible, we are enabling our supervisors to plan their activities in a more flexible way, in accordance with a multi-year SREP. This approach will allow our supervisors to better calibrate the intensity and frequency of their analyses, in line with the individual bank’s vulnerabilities and broader supervisory priorities. This will also streamline the supervisory activities in a proportionate and risk-based manner, as we wouldn’t tick all the boxes every year. As a result, we expect a reduced burden for the banks too.

Importantly, this will not mean less supervision, or a “light touch” approach, but rather more focused and impactful supervision homing in on the most material risks. It will also give us more flexibility to tackle new and emerging risks in a rapidly changing macroeconomic and interest rate environment.

But increasing supervisors’ scope for discretion to prioritise among risks must not come at the expense of lowering the consistency of our supervision across banks. Therefore, alongside allowing our supervisors greater discretion, we are also bolstering our internal controls functions, to preserve the principle that like risks be treated in a like manner.

As part of the reorganisation of ECB Banking Supervision which we undertook in 2020, we introduced a supervisory risk and second line of defence function, which conducts strategic planning, proposes supervisory priorities and contributes to the consistent treatment of all banks via both on-going and ex-post checks.

So, we are increasing supervisors’ discretion to focus their resources on the most important risks, and we are increasing our centralised controls to preserve and even enhance the degree of consistency we achieve in addressing risks across banks. But we also see it as essential that not only supervisors, but also banks and the wider public have a clear view of the assumptions and risk tolerances that drive our supervisory decisions. To this end, we are taking steps to better explain our general methodologies and individual supervisory expectations. In particular, on our website we intend to elaborate on how we set the Pillar 2 requirements and how we assess banks’ credit risk levels.

And we also now summarise our key concerns and findings in executive management letters which we send to individual banks at the end of the SREP process, setting forth what we want the banks to treat as a priority. These letters provide more transparency to the banks on the main relative drivers of the P2R, which is important to ensure they take actions to be able to effectively manage risks and ensure their business model is prudentially sustainable.

Let me stress again: being more risk-focused doesn’t mean being any less intrusive. On the contrary, we are placing increasing emphasis on a structured escalation of our supervisory interventions where banks’ progress is lagging behind clearly set timelines.

One example of our willingness to escalate is leveraged finance, where we acted to address concerning signs of risk build-up as well as a protracted attitude of complacency on the part of some banks.

We are also willing to escalate our interventions in other areas where we see persistent sluggishness in the response from banks, using the whole range of enforcement and sanctioning measures at our disposal. For example, on risk data aggregation and reporting, banks with adequate risk data aggregation and reporting capabilities are still the exception and full adherence to the BCBS 239 principles has yet to be achieved. This is despite the intensity of supervisory pressure in recent years and the large number of findings that have been identified.

Conclusion

Allow me to conclude. Market turmoil always triggers political debates on regulatory reforms, but I think that we should rather focus on the effectiveness of supervision. The most convincing explanation of the rationale of prudential supervision was given in the seminal book by Dewatripont and Tirole published in 1994[2]: the supervisors’ task is monitoring that banks are safe and sound on behalf of depositors, as the latter are too small and dispersed to be able to understand the risks a bank is taking. Effective supervision is the best reassurance for depositors. And in order to deliver effective supervision we need to have a razor-sharp focus on risks, ask difficult questions and request fast and satisfactory remediation of the weaknesses the supervisors identify when performing their job. In embedding the risk-focused approach in our supervision we are emphatically not talking about deprioritising whole areas of prudential risk. Rather, it is about equipping our supervisors with the tools to make informed judgements on how to concentrate their scarce resources on the risks most deserving of their scrutiny and interventions. Notwithstanding the significant improvements made by European banks to strengthen their capital and liquidity position and improve their asset quality, the current events confirm that strong, demanding supervision is needed more than ever. And this is what we are committed to delivering, maturing steadily as we approach our tenth birthday.

Transcript of Q&A following the speech, conducted by Yasmin Osman of Handelsblatt

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room: last Friday we saw an unusually volatile market in banking shares, especially those of Deutsche Bank. How concerned were you when you saw that turbulence on Friday?

Being concerned is part of the normal state of mind of a supervisor.

Did you have a relaxed walk in town?

I always go running. I went running in the forest, in the Frankfurt Stadtwald.

A bad day in the stock market can always come, and that is not a source of concern. What concerned me really was the amount of nervousness, disquiet, that I perceived in the markets among investors – and this is indeed a concern. There is so much attention and concern and nervousness about banks.

Also I must say that what concerned me a bit is that still – notwithstanding all the efforts we have made with regulatory reform – we see that there are markets like the single-name credit default swap (CDS) market which are very opaque, very shallow and very illiquid. With a few millions, you can move the CDS spreads of trillion-euro-asset banks and contaminate stock prices and possibly also deposit outflows. So that is something that concerned me a lot. I think that maybe also in those markets we should have more transparency. Maybe the Financial Stability Board (FSB) should think of reviewing how these markets really work.

More transparency or also different rules? Did you ever think about a short sell ban – of course from the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), not from you?

These types of interventions are not for us to make as prudential supervisors. It’s always the last resort for a supervisor to intervene with such intrusive instruments to prohibit some behaviour. If you have good transparency, for instance by having these types of market centrally cleared rather than having OTC, opaque transactions going on somewhere where you don’t know who’s trading – I think that could already be great progress in this market.

You mentioned that you were surprised by the nervousness of the markets. So how big do you think is the contagion risk or the spillover effect from the US Silicon Valley Bank and the very close Credit Suisse?

First of all, I think it is important that everybody focuses on the fundamentals. So what are the real underlying issues? Again, sometimes I am concerned about how social media starts changing the way in which the debate on banks is driven. In terms of contagion, you can have contagion via direct exposures, which was irrelevant for Silicon Valley Bank and relevant but manageable for Credit Suisse. Then you can have contagion via broader interconnections in the market. Again, this was minimal for Silicon Valley Bank and very relevant for Credit Suisse – it was a G-SIB because it was globally systemically important, so it was important to ensure that there was a process maintaining critical functions in place when the bank went down – an orderly solution of the problem.

The contagion that came from that was via the decision that the Swiss authorities took, which was based on the contractual papers for those instruments in Switzerland. This would not happen in the EU because we don’t have that type of supervisory trigger in the EU. But to totally write down the Additional Tier 1 instruments while the equity holders still maintained some value in their investment, that was a little bit perceived as an inversion of the hierarchy – making Additional Tier 1 basically junior to equity to some extent. This created some turmoil also in the liability structure of our banks, so there was some contagion through that channel. Then there is what I would call mimetic contagion, so what you perceive: Are there similarities? Is something that is there in Silicon Valley Bank also in some banks in other jurisdictions?

I don’t think there was any read-across from Silicon Valley Bank towards any European bank. The bank had a very peculiar – extreme I would say – business model: a concentrated depositor base; concentrated asset side; homogeneity between the two; all tech firms, venture capital; extreme interest rate risk taken. So I think you don’t find this in EU banks really. But of course it drove the attention of investors more on the unrealised losses held at amortised cost in the accounting books, and on the uninsured depositors. That triggered a bit of turmoil.

On Credit Suisse, it's difficult to say. Again, for both: there was an interesting article today in the FT by Robert Armstrong and he quotes Steve Kelly from, I think, Yale University. He says that we, as supervisors, measure banks’ viability through capital to assets, while the markets measure it through capital to business model. And it was the business model aspect that in both banks was not functioning. I counter that we as supervisors also look at business models quite carefully. But it was the business model aspect – investors started checking whether there were similar business models around. I don’t think that they got it right in terms of identifying which ones would have been the target here.

Still, if the markets are panicking, they are not rational in all cases. I was surprised that after this turmoil, you are not so open to a new regulatory debate, as you said. For example, let’s take the too big to fail rules with Credit Suisse: I had always imagined that they would work like precise Swiss clockwork. Now I witnessed an Italo-Western thriller on Sunday evening! Even the Swiss Finance Minister said these rules didn’t work; we would have spilled over into a big financial crisis if we had followed the protocol.

Let me say, first and foremost: what the Swiss did was indeed appreciated. Finding a weekend solution for a G-SIB like Credit Suisse has been very important. We are grateful and appreciate the work they have done. We will need in any case to sit around tables in Basel, or wherever, and discuss any lessons.

But in general I remain confident that the rulebook that we have, also on resolution, is strong. It would work in practice. Of course, we need to understand whether we are there in terms of having all banks, especially the large complex institutions, to be ready to be resolved in a weekend. But if you look at what it has produced, it has produced a significant strengthening of the capital position of G-SIBs, a significant strengthening of the loss-absorbing capacity – the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities – the MREL in our European jargon. All the work banks, supervisors, resolution authorities have done on recovery and resolution planning is very useful. We should be very careful not to throw away the baby with the bathwater.

Another surprise for many people has been the speed with which those deposit outflows happened. So do you think the liquidity coverage ratio rules and the outflow rate should be reconsidered somehow?

I believe that the liquidity coverage ratio is a good supervisory metric. I think the banks need to have liquidity buffers. This is what requires them to have it. It has worked. I am satisfied with the way in which it gives me an idea of where the liquidity of different banks is. You are right: there have been some rather fast outflows of deposits in some cases, so we need to study this and maybe see whether the calibration of certain factors is good.

But honestly, if I look at what happened, for instance, at Silicon Valley Bank: the rule is always a metric that we apply to all the banks. But then there are outlier business models. That model was very concentrated: almost exclusively uninsured large-ticket depositors; all homogeneous in terms of activity; all venture capital tech firms in the same region; also the size of the borrowing. There was also a bit of groupthink between the depositors, borrowers and bank management, so they went out very fast. I haven’t read about the testimony of Michael Barr in the newspapers today; I want to read it carefully and understand it better. But my impression is that, in those cases, it is supervision that needs to look at the business model and – if anything – maybe tailor requirements for that specific business model rather than revise the global standard because of an outlier bank.

What are, in a nutshell, the lessons learned from the Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse crises?

We are being quite vocal on viability of business models. I think that this point is now highlighted here. So we need to be strong in understanding whether a business model is viable. Sometimes it's a slippery slope. Banks and bankers – rightly – think that we should not go there and tell them how they should drive their own machine. So, interfering in business models is difficult for a supervisor. We can tell them we see something that doesn't work, but we cannot tell them which areas of business they should focus on. I think we need to have a very strong focus on business models. We are doing that. We need to maybe sharpen that.

There is another point on Credit Suisse. I don't know if you have read the report that Credit Suisse itself did after Archegos. It's a very candid report and is very interesting, in my view. It shows that it all boils down to internal controls and risk culture. That is a clear finding – they themselves identified it as a learning from that case. If you look at the last days of life of Credit Suisse, they delayed the publication of the annual report as requested by the SEC, and then the publication highlighted material deficiencies in internal controls. So, again internal controls are the backbone of the viability of a bank. That’s why we, as supervisors, do and need to continue to put a lot of emphasis on that.

You also mentioned the geopolitical environment. Do you think banks are already factoring those aspects or those risks in their models?

I would reflect a bit more on the usefulness of models. Models are very useful instruments, I think. They are the best instruments we have to quantify things. But what they do is simple: they take the past, they crunch it into data and then they put the data into a machine and then try to project the future. They work very well when you are in a relatively stable structural environment and you have some sort of cyclical movements around a relatively stable trend. But at the moment we face geopolitical shifts, we have energy shocks, we have climate change, we have digitalisation. When we had the pandemic, we crunched data with our models to try to predict the amount of non-performing loans and we came out with humongous figures. Eventually, luckily enough, these did not materialise because there was a lot of public support and the economy rebounded much faster. Default rates were very small. But, by taking the data from the financial crisis and plugging them into the pandemic, we came out with the wrong answer. So, that for me was a lesson. We need to continue using models, of course – we use them in regulation. But we also need to have expert judgement and some way of adjusting from the outcomes of the model and the way in which we look at risks.

You are leaving at the end of the year. What is your advice to your successor, who is not yet known?

Well, I will think more carefully when we approach the date. I try not to focus too much on it, although sometimes there are times when I’m counting the days, but not always! I think in general, the Single Supervisory Mechanism has been established – after the crisis – with a strong focus on delivering very rigorous, demanding supervision and I think this should be preserved. The teams are very focused on that. There is a strong culture internally, so maintaining this is important.

The other thing that I think is important for banks, which we always tell them – but we should also practice what we preach – is that having internal debates is very important. I try to devote a lot of attention to collaboration between teams, having an open internal debate, listening to different positions, different views. Sometimes diversity is perceived as a sort of woke concept, but it is, in my view, important for a strong organisation. Having diversity of views and internal debates is essential.

You don't know so far what you are doing after your tenure, and so you don't know if you'll leave Frankfurt or stay. If you leave Frankfurt, what place would you miss most?

Well, I spent a lot of time at home looking at a screen during the pandemic! That I won't miss, for sure. What I would definitely miss is running on the river or in the Stadtwald. It's so easy in Frankfurt to be close to nature, in comparison to London or Rome, where I had lived for much of my life. I really appreciate that.

I thought it would maybe be the restaurant Moriki.

Yes, I like it. From time to time I go there, indeed!

It was roughly 1.8% for 2020 and 2021, 1.9% for 2022 and 2.0% for 2023.

Dewatripont, M. and Tirole, J. (1994), The Prudential Regulation of Banks, MIT Press.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts