- SUPERVISION NEWSLETTER

Commercial real estate: connecting the dots

17 August 2022

In December 2021, ECB Banking Supervision announced plans to strengthen its focus on banks’ exposures to vulnerable sectors, including commercial real estate (CRE). This asset class has been one of the most severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, but has also attracted considerable investment during the prolonged low interest rate environment. As inflation picks up and central banks respond by tightening monetary policy, higher interest rates can add to the pressure on the real estate sector. In this context, supervisors need to be more vigilant than ever regarding the possible build-up of vulnerabilities in areas such as collateral valuations and lending standards. Moreover, despite a significant balance sheet clean-up, several banks are still struggling with legacy CRE non-performing loans (NPLs), accumulated in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Across the European banking industry, CRE accounts for as much as 30% of NPLs. Collateral valuation risk is also reflected among the top supervisory priorities.

Against this backdrop, two important CRE projects are currently underway: a CRE on-site inspection campaign (CRE campaign) and a CRE targeted review. Started in 2018, the on-site inspection campaign is covering all CRE portfolios and all areas of credit risk management, including collateral valuation, examining banks’ processes closely and on-site for up to three months. Launched in 2021, the CRE targeted review focused on credit risk management for emerging risks in banks’ domestic CRE portfolios, and used peer benchmarking as a basis for assessing critical elements of risk management. However, while the scope and intensity of these two projects were different, the approach taken was complementary and the findings reinforce each other.

Below we offer an overview of the activities, provide project insights and share good practices for CRE risk management.

Drilling down into the details: the CRE campaign

The ECB campaign on CRE comprises on-site inspections at different banks, all covering the same topics and aligned in terms of scope and work programmes. This harmonised approach renders inspection results highly comparable, providing valuable insights on the current state of play in the banking sector.

The CRE campaign places collateral and CRE asset valuations under closer scrutiny. CRE inspectors work according to the expectation that even if banks have the best risk management framework on paper, if collateral valuation is skewed, then the output will be too. Collateral valuation is crucial, because it drives key risk assessment metrics, such as the loan-to-value ratio when originating and monitoring loans, or the loss given default (LGD) for internal ratings-based (IRB) approaches and IFRS 9 models. It is also a key component for calculating individual provisions. Given the importance of proper collateral valuation, the CRE campaign benefits from certified CRE appraisers in the inspection teams and uses a dedicated tool to challenge collateral valuations.

Another added value of the campaign approach, and more specifically for complex groups, is that CRE usually involves many entities, processes and business lines. In that respect, this campaign offers a valuable gateway for understanding various banking groups’ risk monitoring and steering capabilities.

The CRE campaign has to date involved 40 banking groups. A total of 150 CRE inspectors and appraisers cooperate, supported by a central project management office. The scope of the campaign is sufficiently wide to address a large set of processes, market segments, geographies, portfolios and types of financing. So far, segments like hospitality, retail, office and logistics have been assessed, looking at all types of financing. The main geographies covered are continental Europe, the United Kingdom and North America. The portfolios analysed are the lending book and foreclosed assets. In terms of examination technique, it combines the review of policies and procedures with the analyses of selected credit files and appraisal reports.

Findings span all areas of credit risk management

For most of the banks reviewed, the CRE campaign has raised concerns regarding lending standards, collateral valuation and monitoring processes. Worryingly, a lot of these issues are cross-cutting, extending beyond CRE.

Loan origination: today’s new loans could be tomorrow’s problem

The origination process has been a primary focus of the CRE campaign since the outset, as due diligence early in the process is key for a sustainable risk situation later on. However, inspections show that several banks have no underwriting criteria and pay insufficient attention to cash flows, also in bad times. This suggests that banks have not yet fully integrated the lessons drawn from the global financial crisis: in particular, banks can incur significant losses on collateralised lending, when values fall sharply and defaults increase steeply due to a substantial amount of debtors quickly running into financial distress. Banks should therefore scrutinise expected cash flows both in good and bad market conditions.

Regarding development projects, several banks lack processes for ensuring that sponsors are directly invested in these projects so that they have adequate “skin in the game”, particularly in the event of a downturn. However, for many of the NPLs reviewed, sponsors had provided only a very small portion of the equity capital of those development projects.

Furthermore, quite a few banks with high share of loans that have a large balance falling due at maturity (known as "bullet" or "balloon" loans) failed to apply a debt yield ratio. The debt yield ratio is independent from financial market conditions, as it simply uses the net operating income of the property and the loan amount. It is thus unaffected by fluctuations in interest rates or property values and can help banks compare risks, in addition to more commonly used financial metrics such as the debt service coverage ratio.

Lastly, and due to gaps in their origination policies, banks appear to be insufficiently prepared to properly account for climate and environmental risks in their CRE exposures.

Weaknesses extend to monitoring

Key weaknesses in originating loans are also present in the monitoring process, which can exacerbate the problems identified above. Banks that do not sufficiently monitor tenant risk are particularly affected, as this adds to the lack of origination criteria regarding the tenant’s cash-flow generating capacity. Banks also need to better monitor the ability and willingness of CRE project sponsors to inject more equity if needed. Regarding the early-warning framework and flagging of exposures on the watchlist, several banks lack, or have an inadequate level of key CRE-related metrics; in particular a high loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, a low debt service coverage ratio or a decrease in the collateral market value can be early signals of increased risk. Banks would also benefit from dedicated tools to better identify projects requiring higher scrutiny due to cost overruns, delays in selling the assets or shrinking developer margins.

At portfolio level, quite a few banks do not have commonly defined basic CRE risk metrics, such as the loan-to-value ratio which indicates the ratio of a loan to the value of an asset purchased and pledged as collateral. Neither do they have an overview of the loans subject to refinancing risk (particularly relevant for bullet loans and loans with high balloons), nor of the location of the assets financed (prime versus non-prime). Prime locations are typically centrally located, well connected and of good quality, e.g. a property in a large city or an office in a central business district. In the context of the current crisis, where CRE markets are becoming ever more polarised, asset location is a key factor in identifying vulnerabilities and assessing the overall robustness of CRE portfolios.

In the same vein, banks have in general not sufficiently performed sensitivity analyses on CRE exposures, especially to measure the potential impact of an increase in interest rates. Several banks have not considered off-balance sheet items in their analyses, even though these items represent a large part of CRE exposures. Finally, the scenarios developed in the sensitivity analyses are in general too soft.

Prudential and accounting practices underestimate risks

Banks with a high share of granular domestic CRE exposures, show the most significant provisions gap due to a misclassification of CRE exposures into risk buckets. Several of these banks hold significant legacy non-performing loans portfolios. As their criteria for identifying NPLs leave too much room for interpretation, or do not consider the specificities of CRE finance, these risks are often underestimated. Similar observations apply to forbearance practices, which banks still struggle to implement appropriately. Lastly, many banks had a deficient framework for identifying speculative lending exposures, which are subject to higher risk-weighted capital requirements.

The CRE campaign also revealed that some banks tend to underestimate their specialised lending portfolios and either apply IRB corporate models in a non-conservative manner or fail to develop dedicated models, even when such models were required. With respect to IFRS 9, inspection teams have identified shortcomings in setting triggers to mark a significant increase in credit risk (SICR), such as the use of a quantile approach[1].

Collateral valuation – a key activity lacking safeguards

Despite its importance, collateral valuation is a blind spot for many of the banks reviewed. At several banks, CRE inspectors identified basic shortcomings such as the failure to update appraisal reports according to the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) at least every three years. Banks also failed to perform an ad-hoc revaluation when market conditions changed.

Certain banks also exhibited weaknesses in their selection of appraisers. Appraisers must be independent and submit unbiased valuations, however, some banks accept valuations mandated by clients, even without a reliance letter. They can also call on the same appraiser several times in a row to value a given asset, in the absence of a framework for ensuring any rotation of appraisers. In the same vein, the remuneration of appraisers was in some instances problematic as it did not ensure their independence. Either it was too low to enable them to double-check key data provided by banks or it was too dependent on the collateral’s market value. The higher the market value obtained, the higher the appraiser’s fee. Where banks employed internal appraisers, they were sometimes revealed to be part of the first line of defence or were lacking the required certification.

In several banks, the content of the appraisal reports was not satisfactory. Key information, such as actual rental contracts, validity checks on building permits or the status of the building, was missing. When banks do not provide sufficient information on the assets, valuers have to make their own assumptions, which may differ from actual conditions. Furthermore, for many asset valuations reviewed, the valuation approach and the calibration of parameter values were not adequate, also leading to significant asset value overstatement.

Several banks have not set up a quality review framework for valuers. They do not scrutinise key parameters such as the vacancy status of the property, the capitalisation rate of the project (estimating the return an investor could make on a property), the contractual rents or the maintenance cost of the building, the discount rate or the methodology used (comparable transactions, the discounted cash flow approach, etc.). It is important to stress that even if the appraisal reports come from valuers with recognised international or national certifications (e.g. RICS, Hypzert, ECO), banks are still responsible for setting the collateral valuation.

Completing the CRE picture: the targeted review

Complementing the insights of the CRE campaign described above, the ECB launched a targeted review of commercial real estate risk, conducted off-site. It took a multi-faceted approach, covering 32 banks in the initial data gathering phase and zooming in on a smaller sample in the subsequent phase. The main aim of the review was to assess how prepared those banks are for managing emerging risks in their domestic markets. The review focused on office and retail exposures to understand how banks were managing risk in these sub-sectors undergoing a structural change .

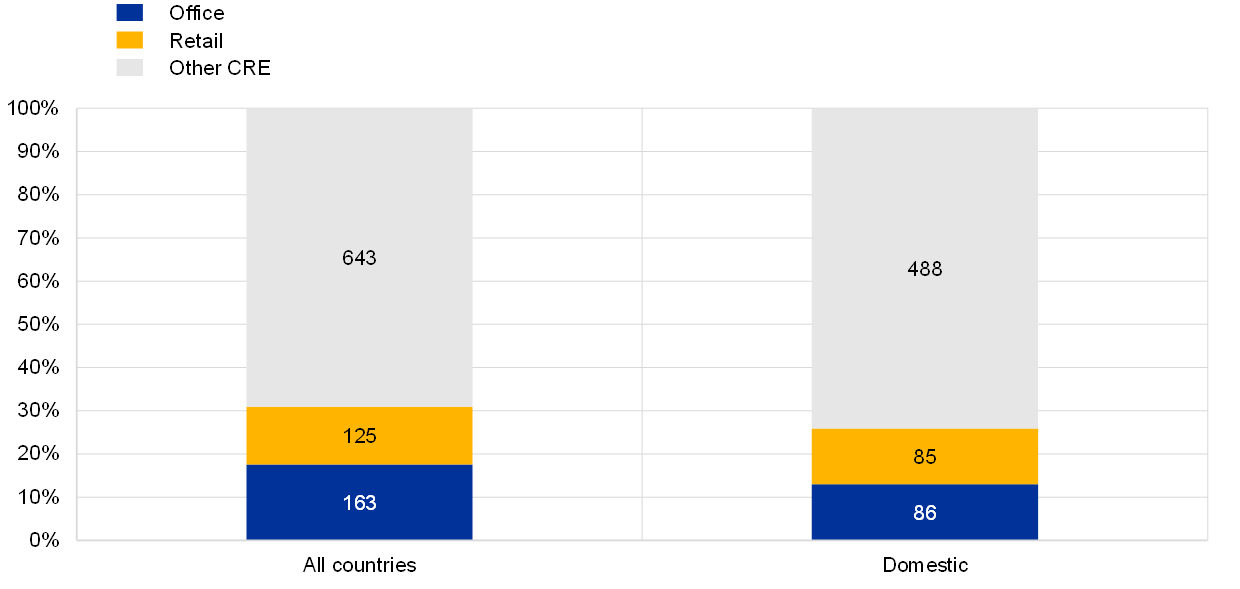

From the collection of data from 32 of the most CRE-exposed banks, we found that 26% of total corporate exposures are commercial real estate, of which 32% are office and retail. This confirms that CRE is a relevant exposure class for banks, highlighting the need to take a closer look at related risks.

Chart 1

Share of commercial real estate exposures of sample of 32 banks

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB Banking Supervision data collected for CRE targeted review.

Note: Commercial real estate definition taken from ESRB recommendation on closing real estate data gaps.

To assess banks’ levels of preparedness, we identified and focused on the most challenging emerging risks:

- Construction costs: the sharp increase in the cost of materials is already having an impact on current construction projects and is expected to affect future supply. However, this is not the only impact. These increases also affect existing properties in terms of basic expenses for the upkeep of the buildings (capital expenditure or ‘capex’ costs) and also the cost of upgrading older buildings (or “retrofitting”).

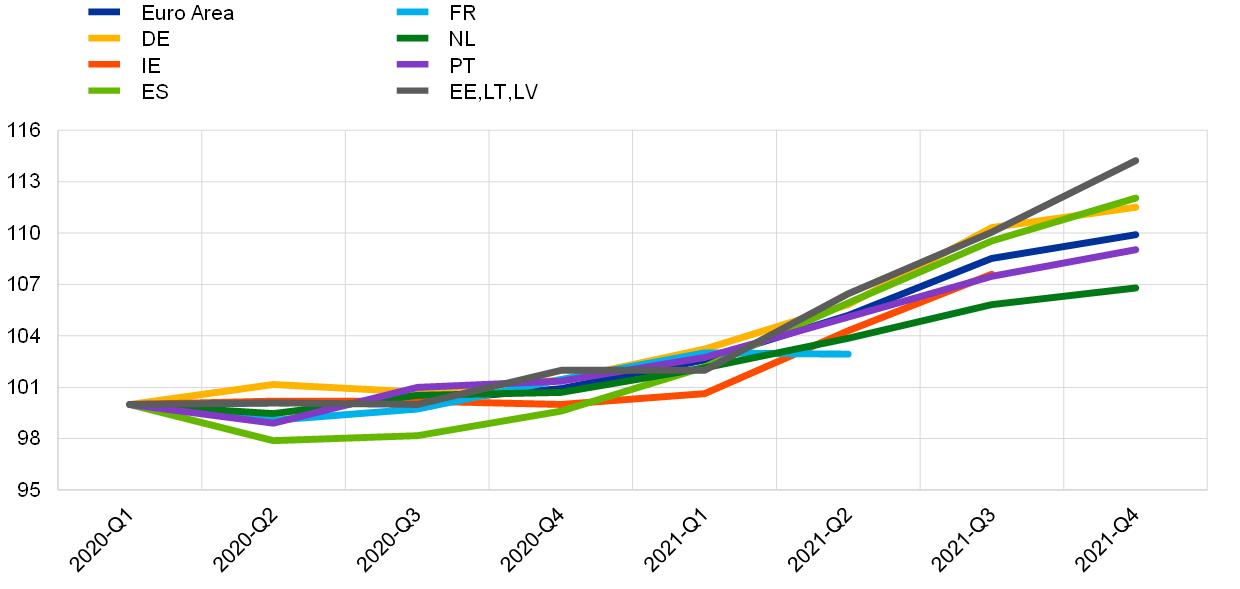

Chart 2

Construction price index

Unadjusted data (2020 = 100):

Source: Eurostat.

Notes: Data for FR available only until 2021 Q2. Data for Baltic countries corresponds to the average of indices for the three economies. - Normalisation of interest rates: interest rates are beginning to normalise, after being low for a long period. This increase will impact credit risk in several ways. Firstly, some borrowers have loans at variable rates. As rates increase, these borrowers’ repayment capacity might deteriorate. Secondly, a material volume of CRE loans have large instalments due at maturity (“bullet” or “balloon” loans). As the cost of lending increases, these borrowers may have problems refinancing their loans at maturity.

- Bifurcation of the CRE market: in recent years, the office and retail market has been going through a structural transformation which has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The result is that while prime properties have remained relatively stable, non-prime assets have become less attractive to investors. In recent years, landlords have had to offer tenants of non-prime buildings greater flexibility in order to retain them. As a result, it may be difficult for landlords to recover their costs through rent increases.

- Climate transition risk: the real estate sector is heavily exposed to both transition and physical climate risk. As a result, it is important that banks understand, mitigate and measure the risk that they could be exposed to. At the core of this, is the collection of accurate climate data which includes energy performance certificate (EPC) ratings for buildings.

The ECB assessed banks’ policies and procedures to understand how these emerging risks are being managed. The following paragraphs outline the main findings identified following this assessment.

Banks are managing CRE risks, but processes and data need improvement

Firstly, while banks generally had risk appetite frameworks which covered some of the emerging risks of the commercial real estate market, certain banks did not have risk limits with the required level of details for the size and complexity of their portfolios. In addition, as mentioned above, non-prime assets have a negative outlook for some sub-asset classes. Despite this, some banks did not understand or manage this risk at a portfolio level, relying instead on a case-by-case assessment through the valuation process.

Secondly, weaknesses were identified with policies and procedures for originating loans. Banks should have clear and detailed underwriting criteria which ensure consistent assessment of borrower risk, yet several banks lacked this level of detail. Coupled with this, some banks did not have a deviation reporting framework which monitored breaches of those underwriting criteria. In addition, several banks did not sufficiently capture realistic assumptions regarding capex and interest risks, especially when carrying out scenario analyses of borrower cash flows. As a result of these weaknesses, the affordability of some borrowers may not be as robust as banks had originally assumed.

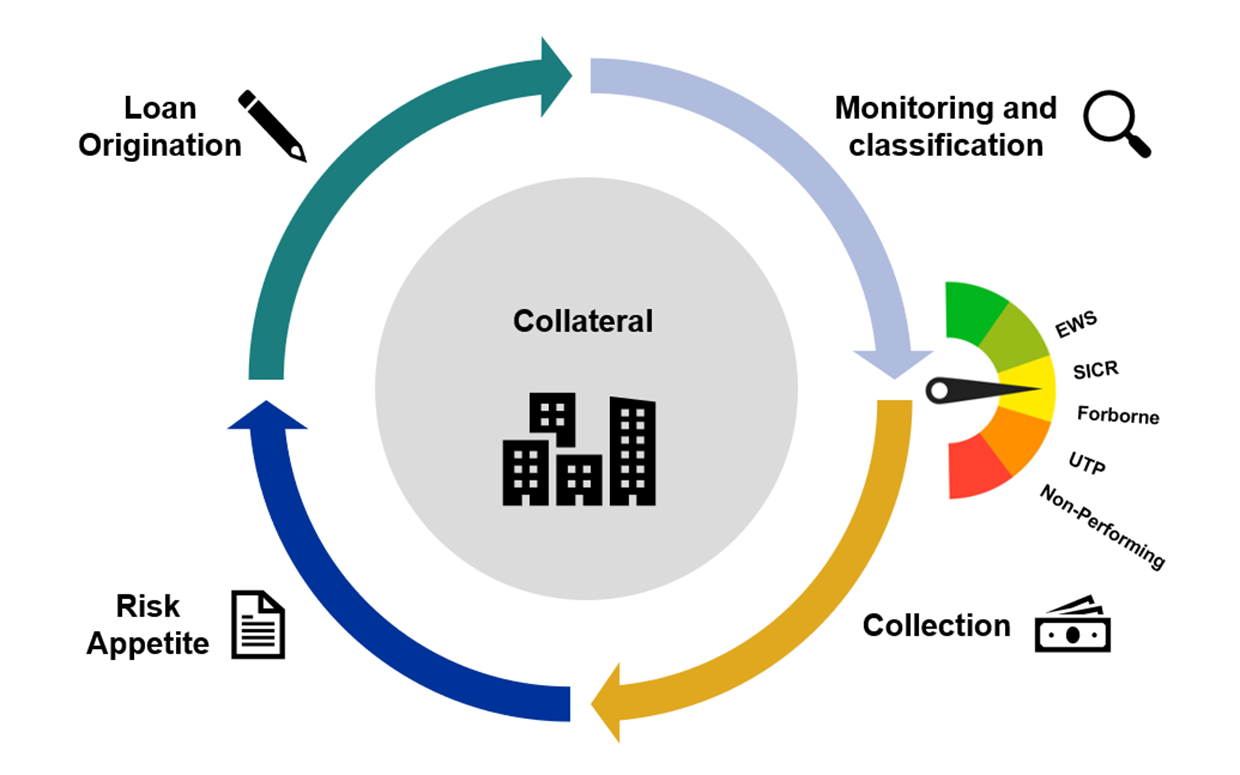

Thirdly, weaknesses were identified with the credit risk management cycle. The credit risk management cycle starts even before a loan is granted and comprises various phases until the loan is repaid or the loan amount is recovered through repossession of collateral (see also Infographic 1 below). As part of the review, the ECB attempted to understand how borrowers who were facing financial difficulties would move through each part of the credit risk cycle. It is important that banks have integrated, clear processes so they can manage any market deterioration efficiently and consistently. However, most banks could not demonstrate that their credit risk cycle was well calibrated. Part of problem lay in banks not consistently using borrower financial information in each part of the cycle, while some banks did not have automated covenant monitoring tools embedded into processes (covenant monitoring alerts banks if debtors show signs of distress). In addition, several banks did not sufficiently capture the forward-looking perspective of borrowers’ financial position when assessing forbearance and unlikely to pay (UTP).

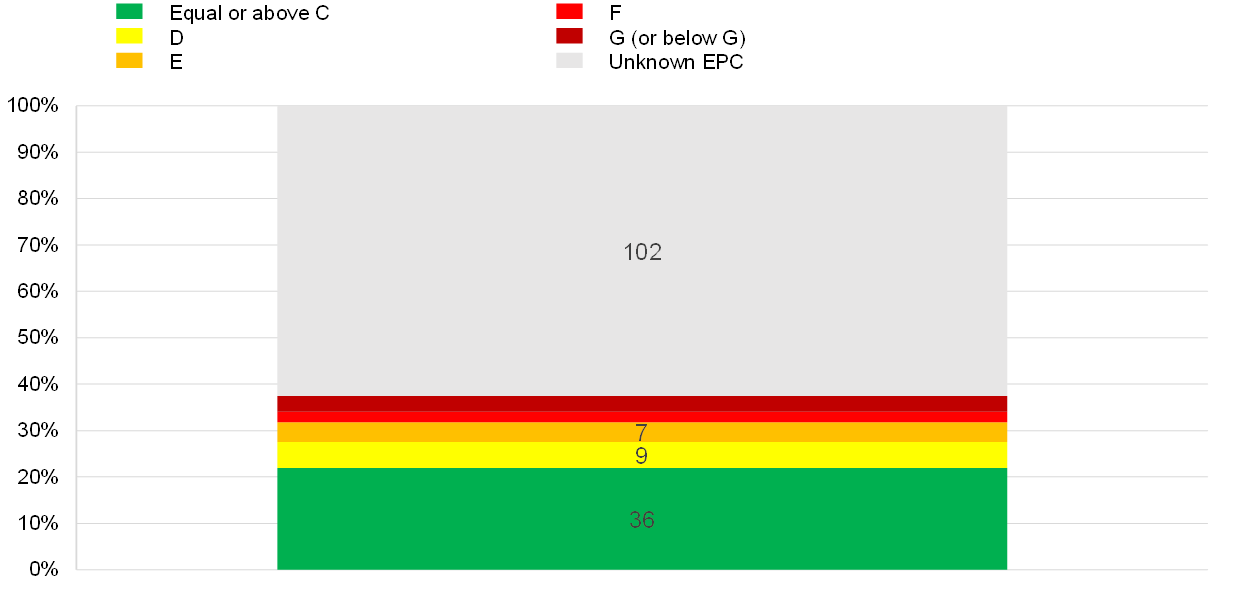

Lastly, with reference to climate risk, the main challenge for banks is collecting accurate data. For this targeted review, we asked banks to provide the EPC data on CRE exposures to understand how exposed banks could be to transition risk. However, only 37% of data could be provided with a large part of this data relying on proxies, which in some cases were not sufficiently robust. For example, in some cases, proxies were purchased externally without any validation of the models while in other cases, no property characteristics were used as inputs for the end estimation. While the ECB acknowledges that there are structural challenges preventing the collection of all data, certain banks were not doing everything they can to collect data, within these structural constraints. Banks therefore risk not being able to fully understand their exposure to transition risk. Further information on banks’ climate risk management practices will become available later in 2022, when the ECB will publish its findings from the thematic review on climate-related and environmental risks.

Chart 3

Breakdown of CRE exposures by EPC rating

(EUR billions)

Source: CRE Targeted Review.

Notes: Not all data corresponds to real EPC data but is heavily sourced on proxies (37% of real data).

Good practices for managing commercial real estate exposures

Strong risk management practices are crucial for a resilient banking sector. Supervisors were pleased to learn that some banks have adopted sound credit risk management practices to improve the robustness of their underwriting processes. The following good practices are drawn both from the CRE campaign and the CRE targeted review. They should be used by banks to help address weaknesses and strengthen how they identify, measure and mitigate CRE risks. The infographic shows the different components of the credit risk management cycle, in a simplified format.

Infographic 1

Overview of credit risk cycle (simplified)

Source: ECB Banking Supervision.

Phase 1 of the credit risk cycle: good practices for risk appetite and risk limits

Banks should have a clear risk appetite framework including processes, limits, and controls which define how much risk they are willing to assume, taking into account the type of exposures, the market segment, the geographies and key risks such as collateral type. Looking at collateral, several banks have developed internal scoring methodologies for consistent risk assessment of each property, taking characteristics such as location, building quality and climate risk aspects into consideration. These banks then limit the volume of the loans they can grant to weak property scores, or only grant loans against these properties if there is an agreed plan to improve the building. This approach was considered as a good practice as it takes a more proactive, portfolio approach to limit risk and limits exposure to the negative effects of a bifurcation in the market (outlined above) and transition risk.

Phase 2 of the credit risk cycle: good practices for loan origination

Banks are expected to have detailed and clear underwriting criteria, including a wide range of risk metrics which are assessed in each loan application. Any deviation from these criteria should be reported so that banks can ensure that they are operating within their own risk appetite. Positively, some banks ensured that risk metrics did not solely rely on the value of collateral with the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, but rather target the cash flows and repayment capacity of the property or borrower. Some banks demonstrated that they consistently used DSCR, ICR, and debt yield in each application, with the latter being especially important for “bullet” or “balloon” loans. Additional metrics were included for development projects, such as the loan-to-cost ratio, the expected developer’s margin as well as the amount of equity to be injected, and proportion of units to be pre-sold or pre-let before a loan is disbursed. The developer’s credibility also needs to be verified. Furthermore, minimum hurdles were in place for each metric, which if not met required mitigating measures prior to granting the loan. Some banks also set tighter hurdle rates for certain riskier types of lending. Where deviations from policy were granted, both the deviations and mitigating measures were recorded, and an overall cap was placed on the total amount of permitted deviations. This ensures that approved loans were largely granted within the established policy requirements.

To ensure loans can withstand a certain amount of stress, banks should carry out sensitivity analyses. The scenarios used for this analysis should be tailored to the specific risk of the loan, such as whether it is “non-recourse”, has a variable interest rate or will have a large instalment due at maturity (leading to refinancing risk). In fact, the normalisation of interest rates and inflationary pressure means that sensitivity analysis is more important than ever for ensuring banks identify vulnerabilities and include mitigants before granting a loan. In this regard, banks with good frameworks ensured that they kept their assumptions up to date with market expectations and included a level of conservatism for the forward-looking assumptions.

When assessing refinancing risk at maturity, banks should ensure that the final instalment amount is likely to be repaid in full, and also carry out a scenario analysis. To give a positive example, some banks compare the number of years it would take the loan to be repaid based on the current cash flows with the remaining time the asset can be used. This is to ensure that if a loan cannot be refinanced by a third party, the bank is still confident of repayment through the cash flows from the asset within a reasonable timeframe. This is good practice for all “bullet” and “balloon” loans.

Phase 3 of the credit risk cycle: good practices for monitoring and classification

For the purpose of this article, monitoring and classification mainly refers to:

- early warning frameworks

- SICR (for banks under IFRS 9)

- forbearance

- UTP.

Each of these components captures a different concept in credit risk management, and in effect, different levels of risk. Banks grant loans based on a comprehensive assessment of credit risk at origination and should have detailed risk metrics and hurdles in place to ensure that certain standards are achieved. Thereafter, once a loan has been granted, each component of the credit risk cycle should have a coherent set of thresholds for each of the elements to capture incremental increases in risk with the main aim to ensure that when a borrower’s financial position is deteriorating, they will move coherently and consistently through the cycle.

The most advanced banks have sophisticated IT systems which capture financial information, covenants, and allow for efficient processes which have policies embedded within the systems. The objective is to allow analysts to focus on assessing credit risk rather than being overly burdened with inefficient processes and complex policies. It also facilitates a consistent approach to assessing risk which can be more easily verified by the second and third lines of defence. This does not mean that assessments should be fully automated. Commercial real estate loans can be quite complex; therefore, a case-by-case and in-depth qualitative assessment is still required, in particular for forbearance and UTP classification. Ultimately, having an efficient framework and tools which support this assessment would allow banks to manage any emerging risks more proactively which may ultimately limit loss.

The CRE campaign identified additional good practices around exposure classification, as noted below:

- Forbearance and the concept of financial difficulties - In the event of delays in construction and/or commercialisation, extension of maturities in the context of CRE finance development appears to be quite common. In this regard, advanced banks define circumstances under which an extension of the loan or other modifications can (or could) be considered as a forbearance measure when the debtor is in financial difficulties, e.g. due to unplanned delays in completing the project and/or obtaining the permits needed or due to a significant decrease in the developer’s margin.

- Forbearance and affordability assessment – Banks must define specific criteria on how to perform affordability assessments in the context of CRE financing. The criteria should take into account the location and condition of the asset, the comparison between the cash flows generated by the asset and the capex needed to maintain its value, and a sensitivity analysis to measure the impact of an increase in interest and/or construction costs. Affordability assessments should be documented. They should be carried out not only when a forbearance measure is granted, but also after the one-year cure period to dispel any concerns regarding the borrower’s ability to comply with post-forbearance measures.

- IFRS 9 backstop triggers – When the probability of a default is dependent on collateral value, especially in the context of non-recourse bullet loans, banks’ IFRS 9 backstop triggers should include significant changes in the value of the asset given as collateral.

- UTP assessments – Banks should have a comprehensive set of UTP triggers based on credit events likely to occur or events specific to the CRE sector, which should go beyond default scenarios. In this regard, the set of triggers at group and entity levels should include for example the loss of major customers/tenants or contractors, lacking refinancing options, continued equity injections from third parties or repeated loan restructuring or, more broadly, justified concerns about the borrower’s future ability to generate stable and sufficient cash flows. UTP assessments should be documented. They should be carried out as soon as a UTP trigger is hit, irrespective of the existence of arrears.

- Regulatory classification of speculative lending – Banks are expected to have in place a proper identification framework for speculative immovable property financing, as this is a riskier category of CRE. It is a good practice if banks expand this to all processes, beyond capital adequacy, such as origination, monitoring, risk classification and IFRS 9 models. Ongoing checks should be performed by the first and second lines of defence.

Spanning all phases of the credit risk cycle: good practices for collateral valuation

The EBA Guidelines on loan origination and monitoring, which have recently come into force, represent a major step forward in strengthening banks’ collateral valuation frameworks. They include a dedicated chapter on collateral valuation, specifying expectations regarding valuation at granting, monitoring and revaluation or the selection of appraisers. The following section shares best practices identified in the CRE campaign, when checking banks’ compliance with the EBA Guidelines.

- Rotation and independence of appraisers – To have an effective rotation of appraisers, a newly appointed appraiser should at the very least double-check the input data used by the previous one, and not take it for granted. This includes descriptive elements such as the land registers. Further, adequate remuneration is key for ensuring the independence of appraisers and advanced banks follow related principles: for instance, the appraiser’s remuneration should not be commensurate with the market value obtained. It is also considered a good practice if banks give appraisers enough time to verify the correctness of the information, to carry out market analyses and to collect proper comparable values.

- Content of the reports – Best-practice appraisal reports specify the basis of the value used (e.g. market value) and provide both a market value and a forced sale value to further highlight potential liquidity issues.

- Review of valuers’ work - The review of valuations should ideally cover not only the assets pledged as collateral, but also banks’ property assets (including foreclosed ones) registered at fair value, given the importance of these valuations in the capital ratios reported by banks. The review should be performed by banks’ internal valuers meeting the qualifications required by the EBA Guidelines. Best-practice banks also ensure that the reviewer is independent from the credit origination process. They further document the review comprehensively for third parties to prove that the bank does not blindly rely on the valuation it receives.

- Hope value and special assumptions in valuations – Banks with advanced processes verify on an ongoing basis that the underlying assumptions are adequate. If discrepancies are identified, banks should order a new valuation based on more robust assumptions in a timely manner. It is also a good practice if banks compare the outcome of these transactions with real transaction prices for similar assets, wherever possible.

- Mortgage lending value – The most advanced banks do not rely only on mortgage lending values for risk management purposes. They need to benchmark them with market values, which should capture liquidity issues.

Integrating climate risk into credit risk management

Accurate and comprehensive data are key in order to integrate climate risk into credit risk management. While there are structural issues affecting the availability and reliability of data, there are various steps banks can take to increase the available data (as also set out in the ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risk). For example, best-practice banks had introduced a mandatory requirement for collecting EPC data when granting a loan. To address the lack of data on stock loans, some banks also requested EPC or other climate-related information when carrying out the annual review of borrowers and required valuers to collect the information when carrying out valuations. This was seen as an efficient way of collecting EPC data as banks have a regulatory requirement to obtain up-to-date valuations every three years for large commercial real estate properties. Advanced banks also request energy consumption data from grid operators. As outlined above, the ECB is finalising its thematic review on climate-related and environmental risks and additional information will become available later in 2022.

The journey is not over

While supervisors and banks are busy following up on the findings from the above exercises, ECB Banking Supervision plans to keep a close eye on emerging risks in the sector. As explained above, banks’ exposures towards vulnerable sectors remain susceptible to potential asset quality deterioration, so it remains key that banks adequately assess and manage them. The ECB will also work on its data infrastructure while the lessons learned from the targeted review and the campaign will feed into supervisory planning for the coming years.

The CRE campaign is still under way, with a relatively high number of inspections already planned for the second half of 2022 and considered for 2023. Leveraging the work of their appraisers, CRE inspectors will deliver a detailed analysis of CRE collateral valuation practices across Europe, including a benchmark exercise with the United Kingdom and United States. Building on these experiences, inspectors involved in the CRE campaign will also look at other vulnerable sectors such as aviation.

Quantiles divide the range of a probability distribution, dividing the distribution in values that lie above and below the quantile. The use of a quantile to define the SICR threshold will ultimately lead to a delay in the reclassification of exposures from stage 1 (performing) to stage 2 (showing a significant increase in credit risk) if the portfolio’s overall credit quality worsens as the value of the quantile changes accordingly.

Banque centrale européenne

Direction générale Communication

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Allemagne

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction autorisée en citant la source

Contacts médias