- THE SUPERVISION BLOG

Hidden leverage and blind spots: addressing banks’ exposures to private market funds[1]

3 June 2025

Private capital markets are growing fast – and so are their links to banks. As complexity and leverage build up outside the regulatory perimeter, risk management of banks, transparency, and regulatory frameworks need to keep pace.

Non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) have become an increasingly important part of the global financial system. The non-bank sector has doubled in size since 2008 and now accounts for over half of financial sector assets in the euro area.[2] The sector comprises entities subject to tight regulation – such as insurers and pension funds – as well as others, operating under lighter regulatory frameworks – like hedge funds or private market funds, including private equity and private credit funds.[3]

While NBFIs help diversify funding sources and support financial integration, their growing size and complexity could affect financial stability.[4] This blog post looks at the evolution of one part of this landscape – private market funds – and what it means for risk management, supervision and policy.

Private markets: growth, interlinkages and systemic risk

Private market funds have grown rapidly over the past decade and are playing an increasingly important role in financial intermediation, with global assets under management standing at €13.2 trillion in 2024. The bulk of these assets are equity instruments. Global assets under management in private credit funds reached more than €2 trillion in June 2024, having increased almost five-fold over the past ten years.[5] Overall, private market funds remain small though relative to global fixed income outstanding (€128 trillion), global banking sector balance sheets (€91 trillion), or global equity markets with a capitalisation of €105 trillion.[6]

In Europe, private markets have grown significantly over the past decade in line with the global trend. During 2024, assets under management in Europe grew to €0.43 trillion for private credit and to €1.2 trillion for private equity, up from €0.15 trillion and €0.4 trillion in 2014 respectively.[7] For comparison, significant institutions in the SSM held €5.7 trillion in loans to non-financial corporations on their books in 2024.[8]

Still, the private credit fund landscape is dominated by the United States and Canada, both in terms of investors and fund domicile. In 2024, around 70% of capital raised for private credit funds originated in this region, compared with 20% in Europe. Similarly, 60% of private credit funds were domiciled in North America, versus 25% in Europe.[9]

Private markets often mirror functions traditionally associated with bank lending, particularly in corporate credit markets. Contributions to private market funds are raised primarily from institutional investors, typically through closed-ended structures.[10] These funds are mostly invested in unlisted companies – either by taking equity stakes (private equity) or by lending to them (private credit).

Both demand and supply-side factors have contributed to the growth of private (credit) markets. On the supply side, investors were seeking higher returns and portfolio diversification during the period of low interest rates. Private credit funds are stepping into spaces where banks may have been constrained by risk appetite limits, and they are increasingly expanding into traditional lending activities.[11] Regulatory arbitrage may play a role in the growth of these markets, given that financial stability risks arising from banks are addressed through regulation and supervision. On the demand side, borrowers have been drawn to the flexibility and speed of deals, and the fact that (costly) credit ratings may not be required, unlike in traditional markets for syndicated bank loans.

As non-banks’ activities expand, risks previously borne by banks are not simply migrating from one sector to the other. Globally, linkages between the sectors are becoming increasingly intertwined.[12] Banks serve as key liquidity providers to NBFIs even if credit intermediation moves outside of the regulatory perimeter. At the same time, banks rely on NBFIs for their own funding through a variety of channels such as deposits or repos.[13] These cross-sector linkages create channels through which shocks can be transmitted, amplified and redistributed across the financial system.[14]

Such vulnerabilities can become exposed during stress episodes and create risks to financial stability. The “dash for cash” episode in March 2020,[15] the collapse of the highly leveraged family office Archegos in March 2021[16] and the UK gilt market crisis in September 2022[17] are examples of how shocks can be amplified and transmitted across the financial system. What ties these episodes together is a combination of high leverage, vulnerabilities to tight liquidity conditions, and opacity. These are structural features of many NBFI business models, which are often subject to lighter regulation than banks – or fall outside traditional regulatory frameworks altogether.

Against this backdrop, private market funds are another clear example of how the growth of non-bank financial intermediation is reshaping the risk landscape. Understanding and managing these risks is increasingly important – for banks, for supervisors and for policymakers.

Assessing the evolving relationship between banks and private market funds

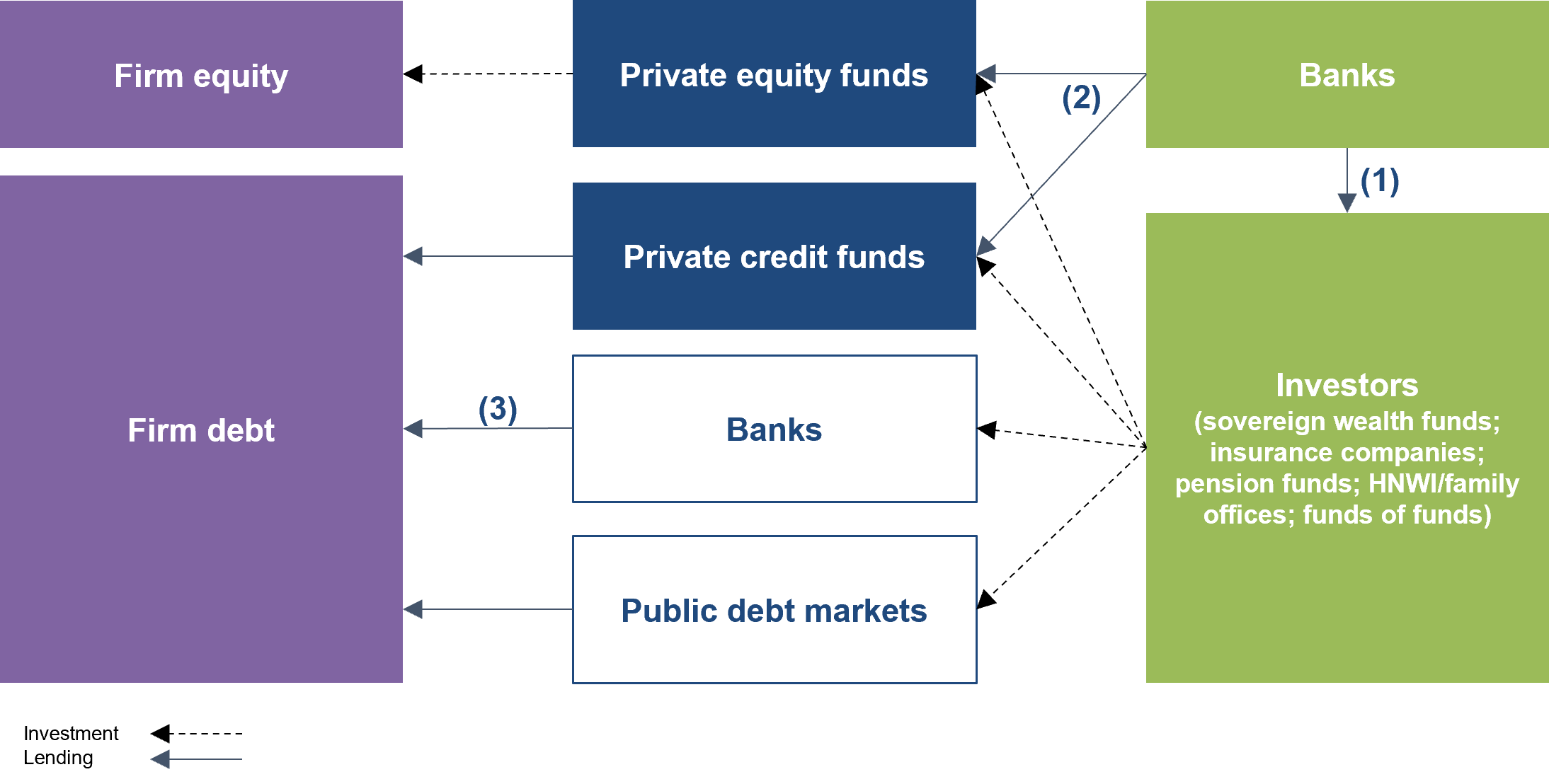

Relationships between banks and non-banks are evolving rapidly and in often complex ways, yet reliable statistical information on these links is largely lacking. This is why ECB Banking Supervision has conducted a review to assess the size and nature of exposures, and risk management for a sample of significant SSM banks.[18] This review found that a few specialised and larger banks engage with private equity and private credit funds through a wide range of financing relationships. Banks lend directly to funds, to fund investors and to the companies held in fund portfolios. Banks sell derivatives that funds and portfolio companies use to hedge interest rate or foreign exchange risk. This, in turn, creates counterparty credit risk exposures for the banks. Some banks are entering the private credit space themselves, either by directly lending to private borrowers using their balance sheets, through their asset management arms, or by partnering with third-party asset managers.

This growing interconnection complicates banks’ risk management. Exposures to private equity and private credit may appear limited in isolation, but they can involve layered leverage – where leverage is introduced at multiple points along the investment chain.[19] This can include borrowed capital at the level of the fund’s investors, the fund itself, or the portfolio companies it controls. What might appear as a straightforward asset-backed loan can turn out to be a complex set of related exposures that share underlying risk drivers and vulnerabilities, particularly when banks are financing several levels along the investment chain.

Enhancing the monitoring of risks related to NBFIs is particularly important in the current risk environment. The end of an environment with low interest rates that spurred some of the growth in private markets, tighter financing conditions, uncertainty in the global economic outlook, and slowing growth could put pressure on leveraged borrowers and expose hidden vulnerabilities in complex financing chains. Without full visibility, banks may underestimate the scale and interconnectedness of the risks they are taking on.

Figure 1

Bank exposures to private equity and private credit funds, schematic simplified presentation

Source: Galbarz, M.-C., Lobbens, M., Marquardt, P. and Villarreal Fraile, M.M. (2024) “Complex exposures to private equity and credit funds require sophisticated risk management”, Supervision Newsletter, 13 November.

In principle, complex structures like layered leverage can also arise in traditional banking. Some private market funds may even operate with lower leverage than banks, which can be a stabilising feature making more equity available to absorb losses. Moreover, banks are usually not first-loss risk takers for the investments that private market funds make. Instead, insurance firms, pension and sovereign wealth funds are typically the equity investors in those funds and would be first in line to bear losses on the funds’ investments. Yet, the level of credit protection banks derive from their senior position in the capital structure can fluctuate during periods of distress, further emphasising the need to monitor the growing interconnectedness between banks and NBFIs.

Yet, private markets differ in one important respect from public markets or traditional bank lending: the lack of availability of reliable and consistent data. Private market funds are subject to lighter disclosure and prudential requirements than banks. Moreover, their investments tend to be illiquid. This means that important risk metrics – such as default histories, loss and recovery rates, and asset valuations – are often unavailable or hard to compare. This lack of transparency makes it harder for markets and supervisors to assess the build-up of risks.

Exposures to private markets as a supervisory concern

Banks’ risk management frameworks have not always kept pace with the growth and complexity of exposures to private markets. Banks often have difficulties to systematically identify when they are co-lenders to the same companies alongside private credit funds or when they have overlapping exposures across funds, investors and portfolio companies. The ECB review found that many banks face challenges when aggregating exposures across business lines or counterparty types, limiting their ability to identify risk concentrations, correlations or potential transmission channels under stress. Given the critical role of good information systems and data on risks in effective risk management, enhancing risk data aggregation and reporting (RDARR) is a longstanding supervisory priority, and the SSM is stepping up pressure on banks that fail to address deficiencies in this area.[20] These findings are a concern for supervisors because banks’ exposures to private markets may imply risks to solvency and liquidity that risk management frameworks do not adequately capture.

There are two reasons for this – insufficiently developed risk management systems within banks and insufficient information on private markets activities. Within banks, risk management of these exposures tends to be fragmented – governed by product type, client segment or business line. Banks may thus not fully recognise when multiple exposures are ultimately linked to the same underlying risk. Valuations are often based on data provided by the funds themselves, which may not be sufficiently challenged by the banks or readily accessible to them.

The lack of a consolidated view of exposures makes it more difficult for banks to identify correlations and concentration risks. Under adverse conditions, exposures that appear manageable on a stand-alone basis may exhibit higher correlations than projected, complicating efforts to manage and mitigate risks.

As regards the reporting of actors on private markets, data availability is generally poor, which impairs banks’ ability to capture, monitor and classify exposures. Addressing these issues will require more consistent and transparent reporting by providers of private credit and private equity. This may increase the cost of doing business in these markets, but it will come with the benefit of enhanced risk management and financial stability.

Improving private disclosure to banks requires better, ideally globally consistent, transparency from private market funds – both within and outside the EU. Better regulatory reporting is essential for supervisory authorities to assess systemic risk. While EU frameworks include some disclosure requirements from private market funds, gaps and data quality issues often prevent a thorough assessment of risks.[21] This challenge is compounded by the fact that many euro area bank exposures are to non-EU funds, underlining the need for enhanced cross-border information sharing.

The regulatory framework is beginning to adapt to these changes – for example, recent revisions to the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD) introduce stricter requirements for loan-originating funds.[22]

To deepen the understanding of banks’ exposures to the non-bank financial sector, ECB Banking Supervision set up a dedicated monitoring exercise in early 2024 asking banks to submit information on the exposures they have towards private markets, which helps to close data gaps.[23] It is one of several steps the ECB has taken to monitor and address NBFI-related risks. As an illustration, the ECB’s thematic review on counterparty credit risk led to the publication of sound practices for governance and management frameworks.[24] An exploratory scenario analysis on counterparty credit risk (CCR) is also currently underway, focusing on vulnerabilities linked to NBFI exposures; aggregate results will be published alongside the 2025 EU-wide stress test report. The topic of CCR is further analysed in the ECB’s financial stability publications.[25]

These efforts complement ongoing work, such as by the European Systemic Risk Board,[26] which focuses on monitoring and assessing systemic risks from non-bank financial intermediation, and the Financial Stability Board (FSB),[27] which conducts annual global monitoring and coordinates policy work to address vulnerabilities in the sector. The FSB’s agenda includes the assessment of risks from money market and open-ended funds, margining practices, and the structure and liquidity of funding markets.

Shedding more light on risks related to private markets

Financial innovation and a diverse financial system, including private markets, can improve the functioning of the financial system by broadening funding sources and investor choice. But as exposures become more complex and interlinked, transparency and risk management need to keep pace with them. Hidden leverage and blind spots may otherwise put individual banks and the financial system under stress.

Banks need to build more robust, integrated risk management frameworks to keep pace with the growing complexity of their exposures to private markets. This includes better data aggregation across business lines, routine stress testing that reflects the potential for correlation and contagion, and clear governance around exposure limits to individual sponsors or fund groups.

Supervisors also have a role to play. Current regulations require banks to adequately manage their financial and non-financial risks. The same principles apply to banks’ exposures to private equity and private credit, including requirements for consolidated risk views and clearer oversight by senior management. ECB Banking Supervision is thus following up on the findings of the recent review to address shortcomings in risk management practices to reflect evolving market structures and exposures – working in close coordination with other supervisory authorities.[28]

But adequate management of risks related to private markets also requires a regulatory response. Business models that flourish because they operate outside of the regulatory perimeter – with limited reporting obligations and light oversight – may generate private returns but at the expense of system-wide stability. The rapid expansion of private markets raises questions about whether existing supervisory and regulatory boundaries remain fit for purpose. A more coordinated approach is needed – within Europe and globally – to close data gaps, align regulatory treatment and ensure that risks accumulating outside the traditional banking perimeter do not go undetected or unmanaged. The consultation on macroprudential policies for NBFIs launched by the European Commission provides an opportunity to introduce targeted tools to address leverage and liquidity mismatch, system-wide stress testing, better data access, and stronger coordination across authorities.[29]

Check out The Supervision Blog and subscribe for future posts.

For topics relating to central banking, why not have a look at The ECB Blog?

I would like to thank Emmanuel Faïk, Philipp Marquardt, Mike Lobbens, and John Roche for their very helpful input. All remaining errors and inaccuracies are my own.

ECB (2024), Eurosystem response to the EU Commission’s consultation on macroprudential policies for non-bank financial intermediation (NBFI), November.

Non-bank financial institutions comprise investment funds, insurance companies, pension funds and other financial intermediaries.

ECB (2025), “Private markets: risks and benefits from financial diversification in the euro area – Box 6”, Financial Stability Review, May.

International Monetary Fund (2024), "Chapter 2 The Rise and Risks of Private Credit", in Global Financial Stability Report, April 2024.

Slok, T., Shah, R., and Galwankar. S., Apollo Global Management (2025), Outlook for private markets 2025: Interest rates higher for longer has important implications for private markets.

Pitchbook (2024), 2024 Annual European PE Breakdown. Please note that for data on private markets, there are fewer official or publicly mandated reporting sources equivalent to those available for public markets. As such, we rely occasionally on data compiled by specialised private-sector providers, which aggregate information from a range of industry participants and market disclosures. While these sources are widely used and considered reliable within the industry, they may vary in coverage and methodology.

Pitchbook (2024), 2024 Annual European PE Breakdown.

European Systemic Risk Board (2024), EU Non-bank Financial Intermediation Risk Monitor 2024, No 9, June.

Block, J., Jang, Y. S., Kaplan, S. N. and Schulze, A. (2024), “A survey of private debt funds”, The Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 13(2), pp. 335-383.

Acharya, V., Cetorelli, N. and Tuckman, B. (2024), “Where Do Banks End and NBFIs Begin?”, NBER Working Paper, No 32316, April.

ECB (2024), “Non-bank financial intermediaries as providers of funding to euro area banks”, Financial Stability Review, May; ECB (2023), “Key linkages between banks and the non-bank financial sector”, Financial Stability Review, May.

Buch, C. and Goldberg, L. (2024), “International Banking and Nonbank Financial Intermediation: Global Liquidity, Regulation, and Implications”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, No 1091, March.

FSB (2022), Report on Liquidity in Core Government Bond Markets, 20 October.

Bouveret, A. (2022), “Leverage and derivatives – the case of Archegos”, ESMA Report on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities Risk Analysis, May.

Pinter, G., Siriwardane, E. and Walker, D. (2024), “What caused the LDI crisis?”, Bank Underground, the blog for Bank of England staff, 26 July.

Galbarz, M.-C., Lobbens, M., Marquardt, P., Villarreal Fraile, M.M. (2024), “Complex exposures to private equity and credit funds require sophisticated risk management”, Supervision Newsletter, 13 November.

ibid. and ECB (2024), “Private markets, public risk? Financial stability implications of alternative funding sources”, Financial Stability Review, May.

See McCaul, E. (2024), “Risk data aggregation and risk reporting: ramping up supervisory effectiveness”, The Supervision Blog, ECB, 15 March.

Under the AIFMD (Directive 2011/61/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011 on Alternative Investment Fund Managers and amending Directives 2003/41/EC and 2009/65/EC and Regulations (EC) No 1060/2009 and (EU) No 1095/2010 (OJ L 174, 1.7.2011, p. 1–73)), fund managers must disclose information on the fund’s investment strategy, risk profile, leverage, fees, valuation, and liquidity arrangements prior to investment, and provide annual reports and regular updates to investors and regulators.

Tothova, M., List, P., Dechert (2024), Changes to the EU landscape for private credit funds in the EU, Alternative Investment Management Association Limited, 17 June.

Results from the first exercise have been published in Galbarz, M.-C., Lobbens, M., Marquardt, P. and Villarreal Fraile, M.M. (2024), “Complex exposures to private equity and credit funds require sophisticated risk management”, Supervision Newsletter, 13 November.

ECB (2023), Sound practices in counterparty credit risk governance and management, October.

ECB (2025), Financial Stability Review, May; Barbieri et al. (2025) “System-wide implications of counterparty credit risk”, Macroprudential Bulletin 26, January.

European Systemic Risk Board (2024), EU Non-bank Financial Intermediation Risk Monitor 2024, No 9, June.

Financial Stability Board (2024), Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation 2024, 16 December.

See, for example, Bank of England (2024), Letter from Rebecca Jackson and Charlotte Gerken: Thematic review of private equity related financing activities, 23 April.

See Holthausen, C. (2024), “Financial intermediation beyond banks: taking a macroprudential approach”, The ECB Blog, ECB, 28 November.