- SPEECH

Enhanced outlook and emerging risk in the banking union

Speech by Andrea Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the University of Naples

Frankfurt am Main, 2 July 2021

I am honoured to be here with you today, even if only virtually, to deliver the lecture that traditionally closes your Master in Economics and Finance programme. I would like to express my warmest congratulations to all students on your graduation today!

Economists are very fond of maths. This is something that you, as specialists in the discipline, have undoubtedly already discovered. Economists create statistical models based on past data to define relationships between economic and financial variables. In this way, past information can be used to project future trajectories. Banks do something similar when they employ internal models to measure risk and quantify capital requirements: they attempt to predict upcoming developments from backward-looking information.

Obviously – and thankfully – there was not a lot of data on how the global, interconnected economy would react to the fallout from a pandemic. Uncertainty has been the defining feature of the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis. As the virus started to spread and countries across the globe gradually went into lockdown, there was no clear evidence on how the health situation would unfold. The promptly implemented public backstop, which was unprecedented in both its magnitude and its range of measures, rescued the economy. But it also made it more difficult to forecast economic developments and potential repercussions for the stability of the banking system. Everybody hoped for a V-shaped recovery – a slump followed by a sharp rise. Then the second wave of infections struck, and fears of a W-shaped recession path with a double-dip recession intensified. What we eventually ended up with is a recession that could best be described as a cursive V, with the small dip of the ligature tracing the second (and third) lockdown periods.

I will start my presentation on a positive note. I will argue that uncertainty has abated and, by all indicators, the economic system is on a path to recovery. As several assessments have shown, our banks remain resilient, well capitalised and capable of helping households, small and medium-sized enterprises and corporates to tackle the challenges posed by the pandemic. Against this backdrop, at the end of September European banking supervision will also take steps towards normalisation as, in the absence of any negative surprises, we plan to repeal our extraordinary recommendation to all banks to refrain from paying dividends and conducting share buy-backs.

However, I will also remind you that, relative to all historical benchmarks, we are going through a peculiar recovery phase. We have just seen the sharpest GDP decline in peacetime for the European economy, but extraordinary policy support has meant bankruptcies and non-performing loans (NPLs) have barely reflected this. Banks’ asset quality will deteriorate when the bulk of the public emergency support is withdrawn, but most likely by less than initially estimated, as this is difficult to quantify.

As supervisors we remain sharply focused on ensuring that all banks are duly equipped to make it through the last phase of this crisis and accompany the economy out of the main emergency support measures, with no disruptions and at the minimum cost in the medium to long term. This will only be achieved under two conditions: first, supervisors and banks must not lower their guard too soon, and second, credit risk management practices must take a forward-looking approach and keep up with the specific challenges created by the pandemic. Some banks still have work to do, but our ongoing supervisory efforts are promoting good practices and raising the bar for credit risk controls.

Equally importantly, I will try to explain that if we do not pay sufficient attention to banks’ governance and risk controls, extraordinary fiscal and monetary measures like those that proved necessary in this crisis could end up reviving threats to financial stability. I am referring to the excessive search for yield, which feeds the increasing appetite for leverage, complexity and opaqueness in financial markets. I will argue that, in a financial environment characterised by interconnectedness between banks and the so-called shadow banking sector, excessive risk-taking in markets such as the leveraged credit and equity-related derivatives markets threatens to leave banks overly exposed to sudden adjustments and asset price corrections. Despite the financial market turbulence that accompanied the outbreak of the pandemic, we have been observing continued exuberance in those markets. This is concerning, and banks have not responded sufficiently to our supervisory calls for prudence. In our view, these developments warrant more intense supervisory scrutiny and action.

The pandemic outlook

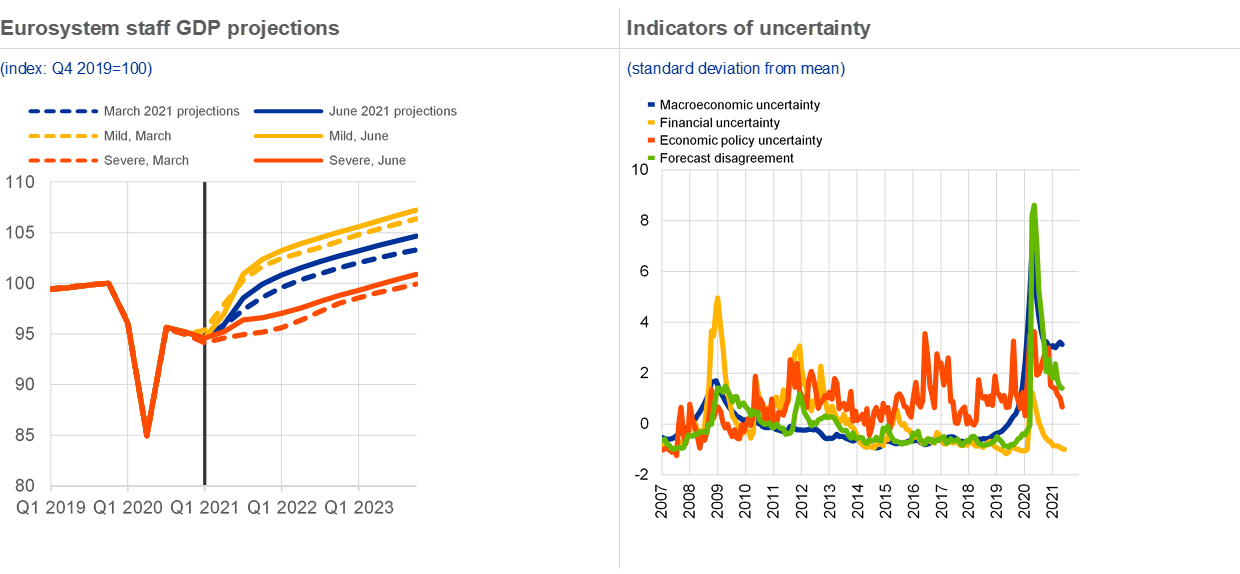

In the initial phase of the pandemic, macroeconomic uncertainty reached levels never recorded before. But in recent months the economic outlook has brightened continuously, and uncertainty has strongly abated (Chart 1).

Chart 1

Source: ECB.

Notes: In the left-hand panel, the vertical line marks the start of the projection horizon. In the right-hand panel, all measures of uncertainty are standardised to mean zero and unit standard deviation over the full horizon starting in June 1991. A value of 2 should be read as meaning that the uncertainty measure exceeds its historical average level by two standard deviations. The latest observations are for May 2021.

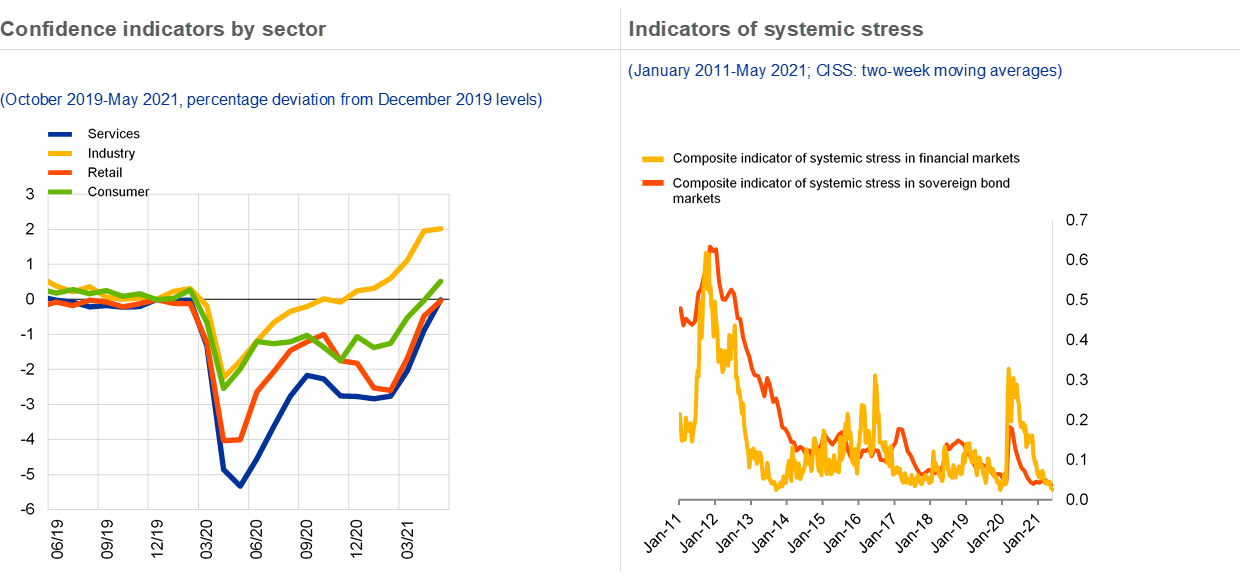

Confidence in the retail and services sectors has recovered to pre-crisis levels, while the industrial sector is enjoying pronounced optimism. Financial market stress has receded to pre-pandemic levels as well (Chart 2). Thanks to the swift, unprecedented monetary, prudential and fiscal measures, the recovery from the first economic hit from the pandemic has been rapid, and the effect of the second wave of restrictions much attenuated.

Chart 2

Source: ECB.

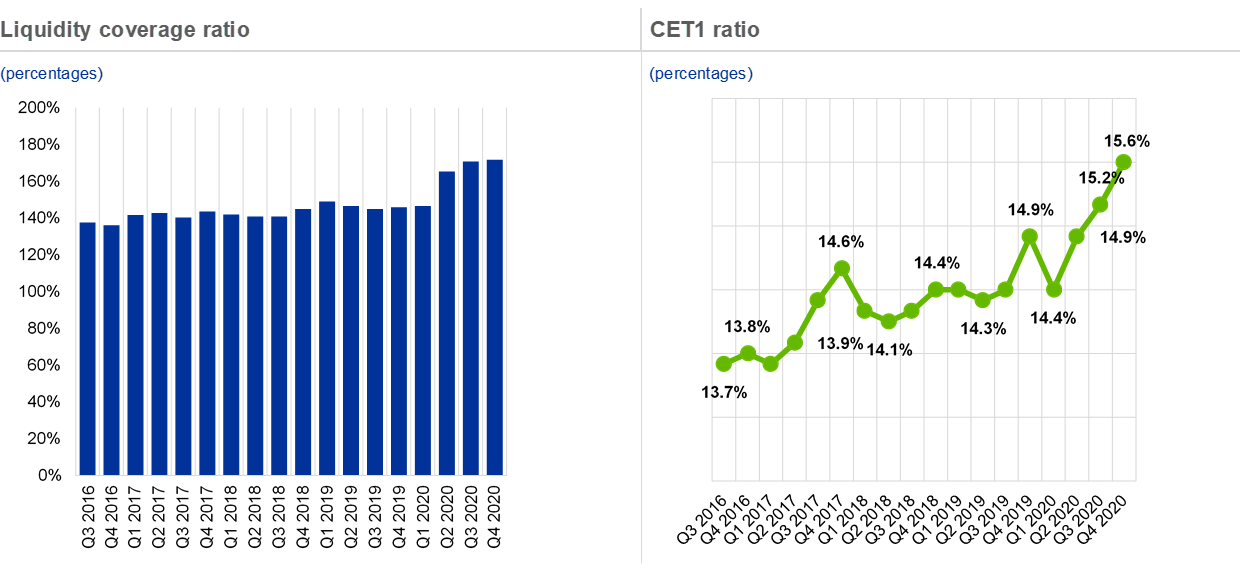

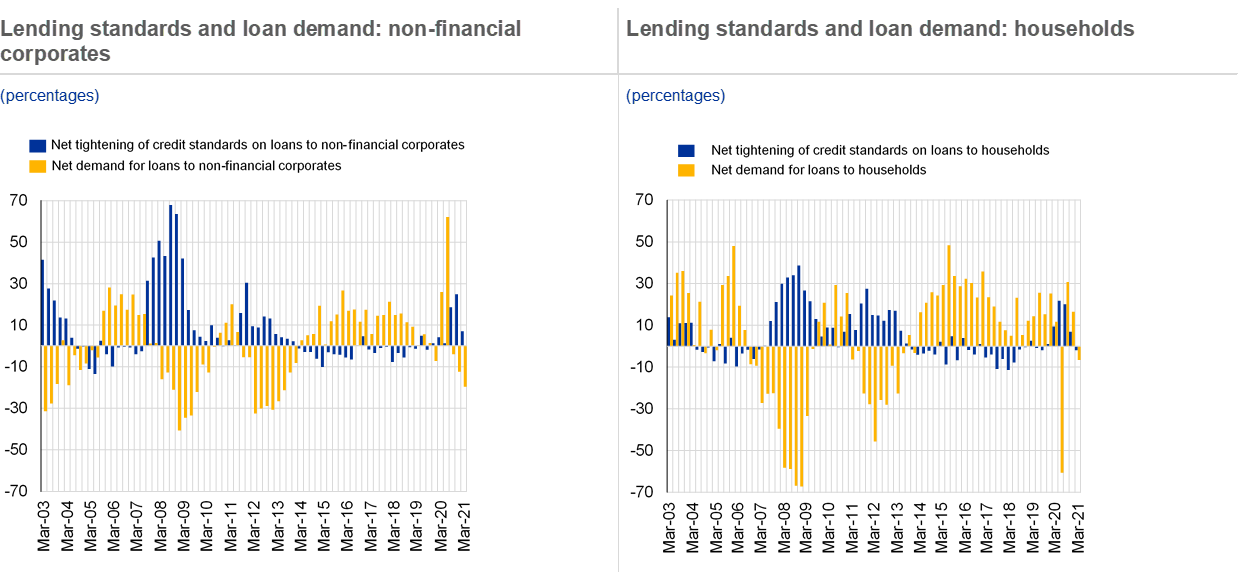

Banks in the banking union faced the pandemic armed with much stronger capital and liquidity positions than they did the great financial crisis. The Common Equity Tier 1 capital ratio of supervised banks fell slightly in the first quarter of 2020, but it then resumed its upward trend, with the year-end ratio higher in 2020 than it was in 2019. The strong capital position has been the result of the Basel III post-crisis reforms and the continued and rigorous supervisory scrutiny during the first six years of European banking supervision. The post-financial crisis reforms initially met with resistance from the banking industry, which was concerned that the reforms would jeopardise the economic recovery and could act as a drag on growth and job creation. But regulators and supervisors were convinced that the long-term benefits of a more resilient banking sector would far outweigh any potential short-term costs, and these costs could in any case be mitigated by appropriately paced phase-in arrangements. Some of the reforms ultimately adopted obliged banks to build up different kinds of capital buffers that could be used in times of adversity.

Differently from the last major crisis, the COVID-19 shock did not emanate from the financial sector. But even if banks were not at the origin of the problem this time, there was a palpable risk that they could aggravate the situation. Spiking uncertainty, falling confidence and increasing risk aversion threatened to trigger a procyclical reaction by banks and to amplify the downturn. To stop this from happening, ECB Banking Supervision allowed banks to draw on regulatory capital and liquidity buffers. This considerably increased the distance between banks’ capital and liquidity levels and their regulatory triggers, so banks had more leeway to lend and absorb losses.

Chart 3

Source: Supervisory reporting.

Note: Sample comprises 112 SIs as at the fourth quarter of 2020.

Together with the sizeable and coordinated fiscal and monetary expansion, as well as loan moratoria and public loan guarantees, these measures succeeded in averting a deeply procyclical reaction by the banking sector and in providing much-needed credit to households and firms. Lending standards did tighten during the pandemic, albeit much less so than during the great financial crisis (Chart 4), and credit volumes increased during the first months of the pandemic.

Chart 4

Source: Euro area bank lending survey.

Note: A positive net percentage indicates that a larger proportion of banks have tightened credit standards (“net tightening”), whereas a negative net percentage indicates that a larger proportion of banks have eased credit standards (“net easing”).

When the pandemic first hit the economy, we issued a recommendation to banks to restrict dividends and share buy-backs. In that environment of unprecedented uncertainty, it was only prudent to preserve as much capital as possible in the banking system so that it could be used to absorb losses and support lending. And this exceptional measure seems to have had the intended effect. Analysis by the Banco de España and the ECB found that banks whose dividend decisions were covered by the recommendation granted more credit than those whose dividend decisions predated the recommendation.[1]

Following the revision to our recommendation on 15 December, banks under the ECB’s supervision resumed payments within prudent parameters, which amounted to around one-third of pre-crisis payouts. We have been pleased to see that banks adhered to our recommendation.

Based on the latest macroeconomic projections, we are confident that a robust recovery is taking shape. This makes banks’ capital projections more reliable. We have also worked intensely to challenge the way banks measure and manage credit risk in order to foster more reliable estimates of future capital trajectories. And this year’s stress test will offer insights into how bank balance sheets would be changing in the face of renewed adversity. As a result, we will be able to discuss banks’ payments plans on an individual basis. Therefore, in the absence of materially adverse developments, we plan to repeal our recommendation on dividends as of the end of the third quarter of this year. We will return to our ordinary scrutiny of dividends and share buy-backs, based on a careful forward-looking assessment of each bank’s individual capital planning. But we do expect distribution plans to remain prudent. They need to be commensurate with banks’ internal capacity to generate capital and they need to be able to withstand the potential impact of a deterioration in the quality of exposures. The results of the stress test exercise will help to inform our discussions here as well.

The importance of sound credit risk management practices

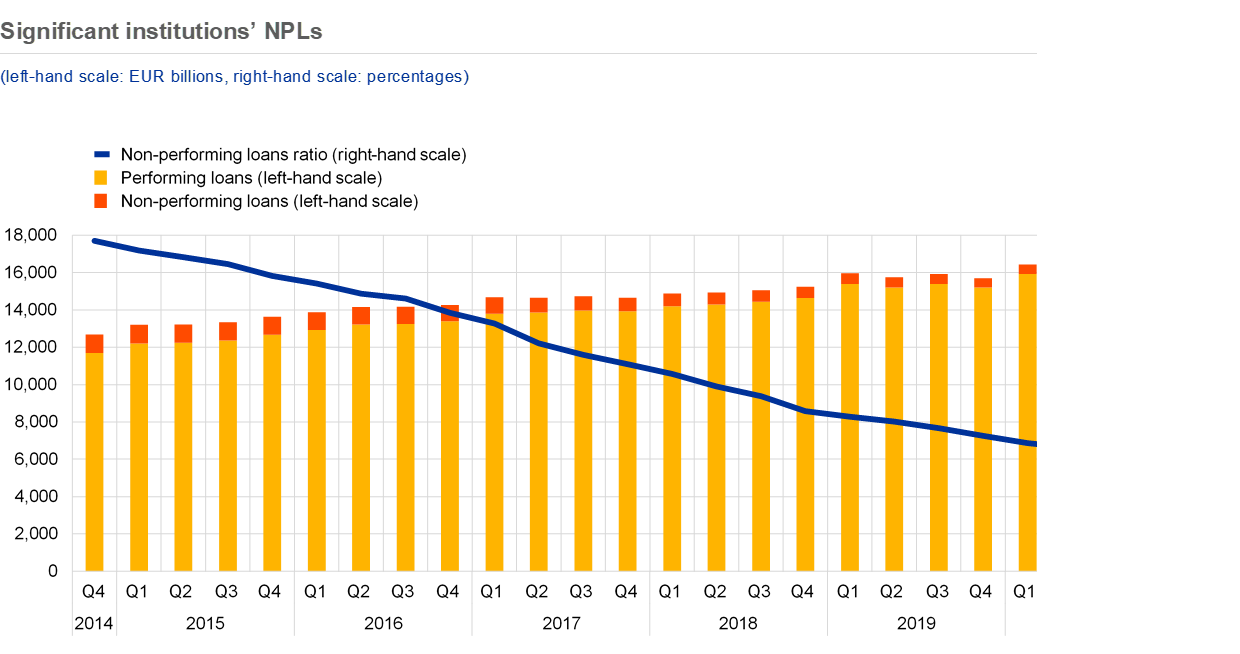

Based on data about past recessions, there was a fear that the deepest European recession in peacetime could cause a wave of bankruptcies and a massive deterioration in banks’ asset quality. But bankruptcy levels actually fell considerably during 2020, and there has been no major impact on the ratio of NPLs to total loans (Chart 5). One of the unique features of this crisis is that, amid an enormous drop in economic output, the NPLs ratio continues to fall. But it is not only the pandemic hit on the economy that has been exceptional, the policy response to it has been unprecedented as well.

Chart 5

Source: Supervisory reporting.

Note: Changing sample.

Nevertheless, sooner or later loan moratoria and public loan guarantees will be fully phased out. Fiscal measures supporting borrowers may become more selective and eventually be phased out as well. To avoid any surprises in asset quality later on, we sent letters to banks’ CEOs in July and December of last year to stress the importance of accurately and proactively managing credit risk. Over the past few months, we have taken an in-depth look into banks’ credit management practices. Results have been mixed: while most banks have adjusted their credit risk controls in line with our supervisory expectations and to reflect the specific features of this crisis, some banks showed substantial gaps that need to be addressed. Some banks’ early warning systems and procedures for assessing borrowers’ unlikeliness to pay are overly reliant on ineffective indicators, outdated ratings and backward-looking information. This brings us back to my first point: backward-looking data have generally been of limited use during this pandemic. The gaps also relate to early arrears management, borrower engagement and forbearance. We will follow up on the identified deficiencies in our Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process, and through operational acts, if necessary.

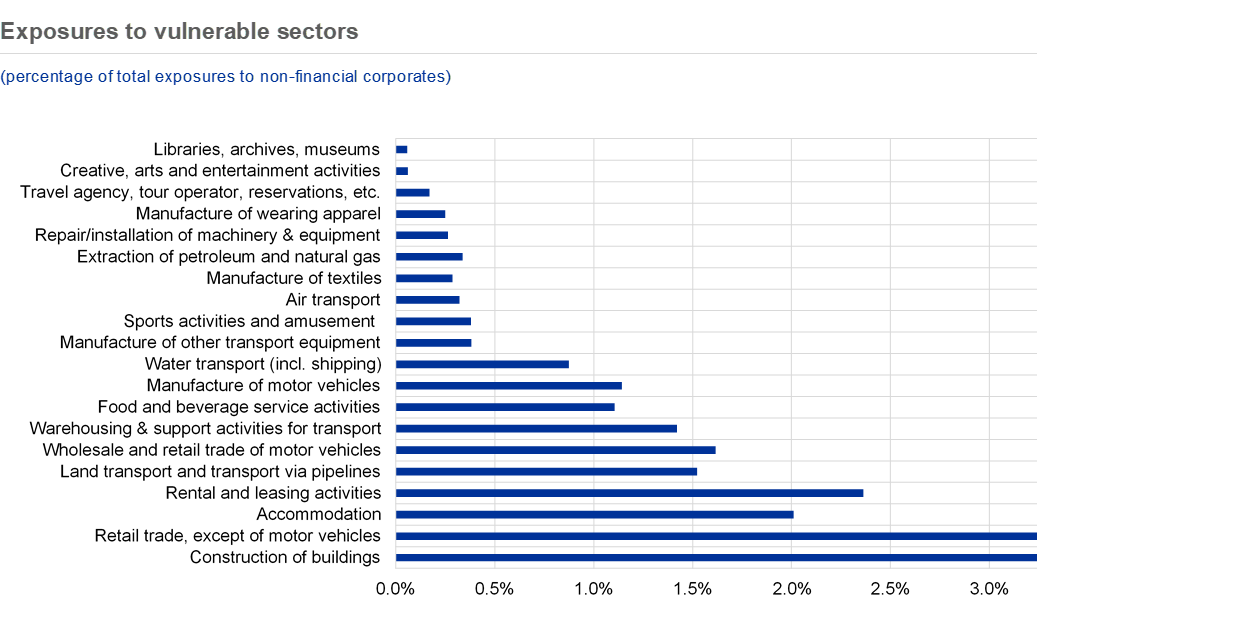

ECB Banking Supervision also performed a deep-dive analysis into certain sectors that may be more adversely affected by the economic impact of the pandemic. We adopted a targeted approach to the credit risk of directly supervised banks that are exposed to vulnerable business sectors (Chart 6). Earlier this year, we launched a targeted review of the accommodation and food services sector. In addition to gaps in early warning systems and procedures for assessing borrowers’ unlikeliness to pay, not all banks have sufficiently adjusted default probabilities used for loan loss provisioning to account for borrowers’ vulnerabilities in this sector. We were concerned, and somewhat surprised, to see that some banks have even lowered those default probabilities, potentially reflecting the impact of public support measures (Chart 7). This warrants closer supervisory scrutiny.

Chart 6

Source: AnaCredit data as at the fourth quarter of 2020.

Notes: Sample comprises 106 significant institutions. Exposures granted by subsidiaries outside the euro area are not included in AnaCredit.

Chart 7

Source: ECB ad hoc data collection.

Note: Preliminary evidence.

The proactive management of impaired loans is beneficial for economic growth and financial stability. High NPL stocks weigh on bank profitability and their ability to provide new credit, and may indicate that there are deeper corporate viability issues in the economy. This, in turn, would be a drag on investment and growth. In an empirical study using a global sample of around 100 economies, economists from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)[2] have found that reductions in NPLs are associated with faster economic growth, higher corporate investment and lower unemployment. A recent study by ECB economists[3] shows a similar picture for euro area countries, where higher NPLs are found to depress bank lending and lead to slower GDP growth. In Italy[4], it has been documented that exogenous, unexpected changes in bank NPL ratios influenced credit supply. And ECB economists[5] find that the link can work both ways: weak banks are more likely to delay restructuring loans to their weak corporate customers, while lending to zombie firms can deepen a bank’s financial distress. Early management of distressed exposures is also beneficial for viable borrowers, as forbearance and restructuring measures, if taken at an early stage, could restore the sustainability of debt positions for bank customers and enable them to contribute to the recovery. Proactive credit management helps both growth and stability, and ECB Banking Supervision will ensure that banks’ practices are fit for purpose.

Even though the signs of economic recovery are firming up, the jury is still out on the ultimate fallout from the pandemic in terms of NPLs. Nevertheless, market sentiment has brightened noticeably. As a consequence, banks have started to project higher profitability owing to reduced loan loss provisions (Chart 8). This is another unique feature of this crisis: historically, banks have released provisions only once bankruptcies have started to fall again. This time, banks are already projecting reduced provisions even though the rise in bankruptcies has yet to materialise.

Chart 8

Source: FINREP for actual values, COVID-19 reporting for the projections.

Notes: Sample sizes and ratio definitions differ between actual values and projections owing to data availability. Cost of risk is the ratio of the adjustments in allowances for estimated loan losses during the relevant period (annualised) divided by the total amount of loans and advances subject to impairment.

Emerging risk

We are growing increasingly concerned that more could be at stake than just the direct impact of the pandemic on borrowers’ creditworthiness and banks’ NPLs.

Given the financial market turbulence triggered by the outbreak of the pandemic, and the unprecedented public backstop put in place to cope with what is considered the deepest recession since the Second World War, we need to focus on the growing signs of market complacency and excessive search for yield, and on the threat these phenomena may pose to the delicate process of economic recovery. Unprecedented levels of liquidity and a wide array of government support measures have managed to dampen financial market volatility and keep market participants’ uncertainty at bay. In doing so, the measures have successfully supported the wider economy and shielded it from downside risks in the short run. However, those same measures may be fomenting and exacerbating an environment of muted risk sentiment and depressed profitability. Evidence of mispricing of risk in some market segments was already present before the pandemic, and the appetite for financial leverage and financial complexity had also been growing. History tells us that such trends are generally not sustainable in the long run and, when public support is eventually withdrawn, they leave financial market participants overly exposed to any unexpected adjustments.

Leverage and complexity in credit and financial markets are fuelled by a wider range of financial entities than just banks. However, banks generally play an active role in financing other financial institutions. The interconnectedness with other financial entities can expose the banking sector to potentially large direct and indirect losses if these exposures are not properly managed.

If we want to see a smooth and solid recovery from the pandemic, banks must apply the lessons learned from past crises, particularly at this delicate juncture.

Let me now elaborate further on the risks that we see building up. I will offer a few observations on the leveraged finance business and talk about some incidents we have witnessed in the market for equity-related derivative instruments.

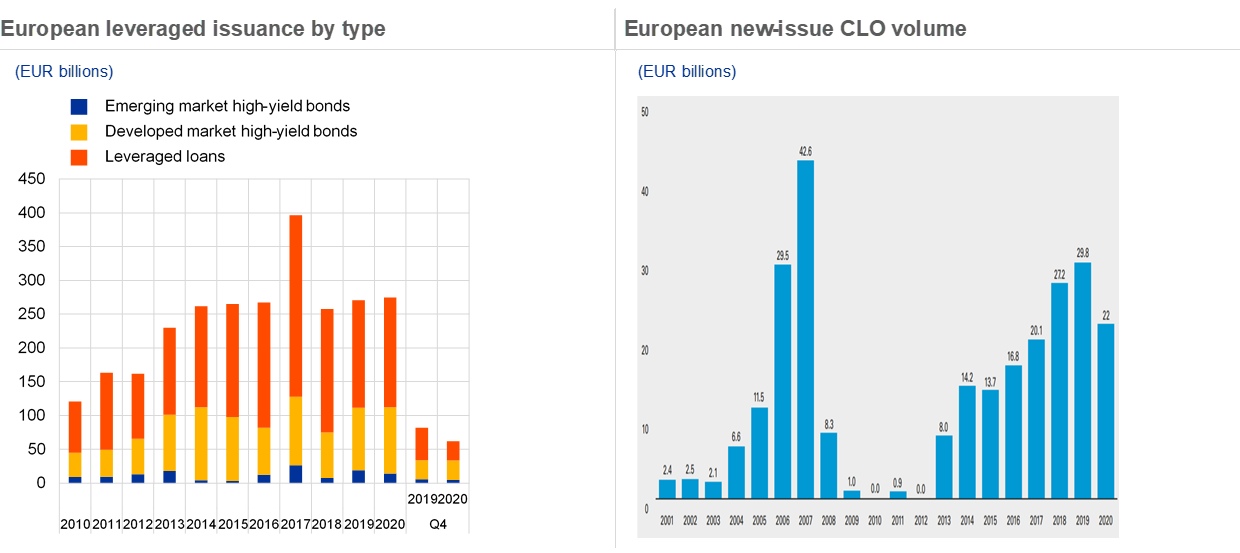

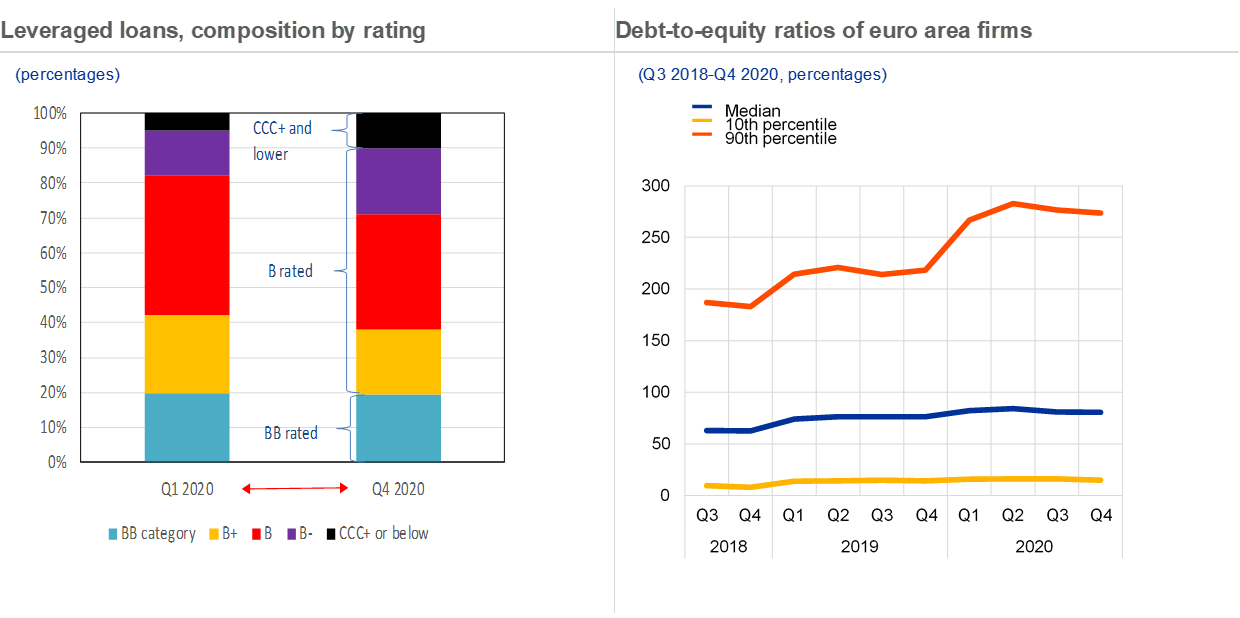

A case in point is the steady growth of the leveraged loan and high-yield bond markets observed since the great financial crisis (Chart 9). These markets mainly feature highly indebted corporate counterparties of speculative-grade credit quality (i.e. below BBB- rating). European banks’ willingness to engage in this business reflects their appetite for high returns, which can be achieved through remuneration for speculative-grade credit risk and attractive fees linked to loan syndication activities. Loan syndication is the process where the originating bank first underwrites the loan and then places part or all of it within a network of underwriters, such as funds and other banks, retaining any residual component.

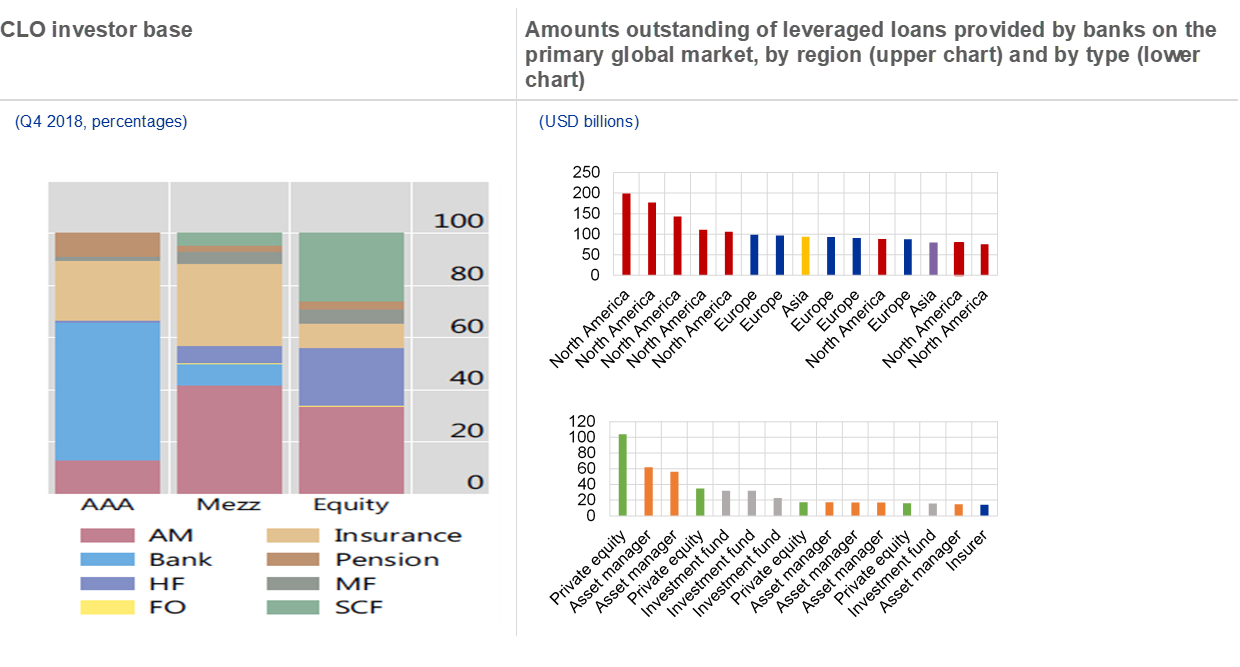

The market for leveraged credit gradually broadened its investor base at the global level, which has contributed to its expansion. The resurgence of collateralised loan obligations (CLOs) (Chart 9) – financial vehicles that invest in leveraged loans and securitise them in tranches of different risk – is a prime example of this. Banks, however, remain the largest holders of leveraged loans, followed by CLOs, insurers, pension funds and other investors.

Meanwhile, high-yield bonds – which are normally issued by the same leveraged corporate borrowers in the context of the same credit agreements that use leveraged loans as a complementary source of funding – are mostly bought by mutual funds and exchange-traded funds, pension funds, hedge funds and insurers[6].

Chart 9

Sources: Left-hand panel, AFME; right-hand panel, Creditflux.

On the one hand, the broadening of the investor base to non-bank financial entities has likely reduced banks’ direct exposure to leveraged credit. On the other hand, it has also probably increased interconnectedness and opacity in this market, elevating banks’ indirect exposure and the concentration of banks and non-bank entities in similar leveraged debt exposures (Chart 10). Within CLOs, for instance, most of the riskier (junior and mezzanine) tranches are sold to asset managers, insurance funds, hedge funds and structured credit funds, while most senior tranches are bought by banks (Chart 10). And although CLOs are normally structured in such a way as to avoid many of the risky features that were typical of collateralised debt obligations in the run-up to the great financial crisis, they unavoidably increase interconnectedness and concentrations in the market for risky credit[7]. I will return to this problem later on in my presentation.

Chart 10

Source: Left-hand panel, BIS; right-hand panel, IMF Global Financial Stability Report, April 2020, based on Dealogic data and IMF calculations.

Note: In the left-hand panel, AM stands for asset managers; HF for hedge funds; FO for family offices; MF for mutual funds and SCF for structured credit funds.

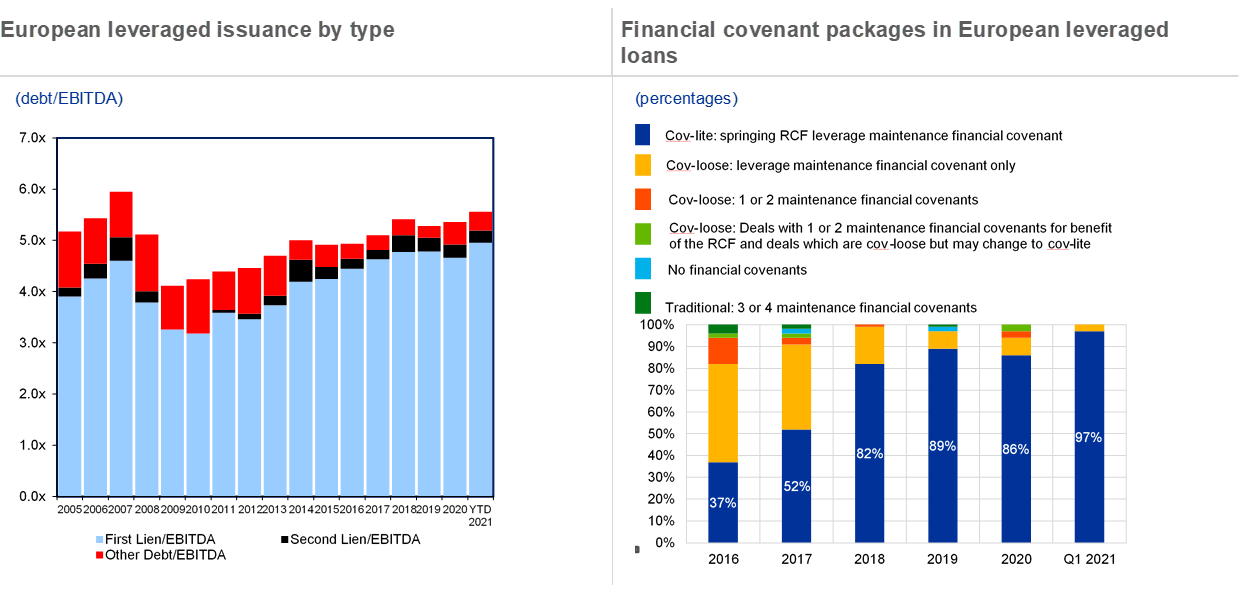

The expansion of the market in a search-for-yield environment was characterised by increasingly loose underwriting standards. On the one hand, leveraged loans were underwritten to attract corporates with increasingly higher levels of leverage, as shown by the borrowers’ outstanding debt becoming an ever-growing multiple of their earning capacity (as measured by earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation – Chart 11). On the other hand, these same loans were structured to include fewer and fewer covenants, i.e. the contractual restrictions and financial parameters governing how corporate borrowers can operate and which are designed to safeguard the interests of investors (Chart 11). This implies that investor protection has weakened.

The ECB looked into banks’ risk management practices in the area of leveraged lending as early as 2017. At the time, based on survey evidence, we realised that vulnerabilities similar to the ones I have just described could potentially be building up among a subset of supervised entities that were very active on the market. The ECB then issued dedicated guidance[8] setting out supervisory expectations on a range of specific aspects of the leveraged lending business, including: (i) risk appetite and governance; (ii) underwriting and loan syndication standards; (iii) policies and procedures for long-term investments in leveraged loans, and (iv) policies and procedures for participating in secondary markets. Despite the clarity of our guidance and the caution we urged, we have been seeing a further deterioration in underwriting standards among the significant banks that are most active in the market. We have been reporting on those developments in our Supervision Newsletter. Based on data from the fourth quarter of 2020, and in line with our own definition of a leveraged loan[9], more than half of the leveraged loans originating from banks under European banking supervision that are most active in the business show a leverage factor (i.e. a debt-to-EBITDA factor) of more than six and are either covenant-lite or have no covenants at all.

Chart 11

Source: Left-hand panel: LCD, an offering of S&P Global Market Intelligence; right-hand panel: Reorg.

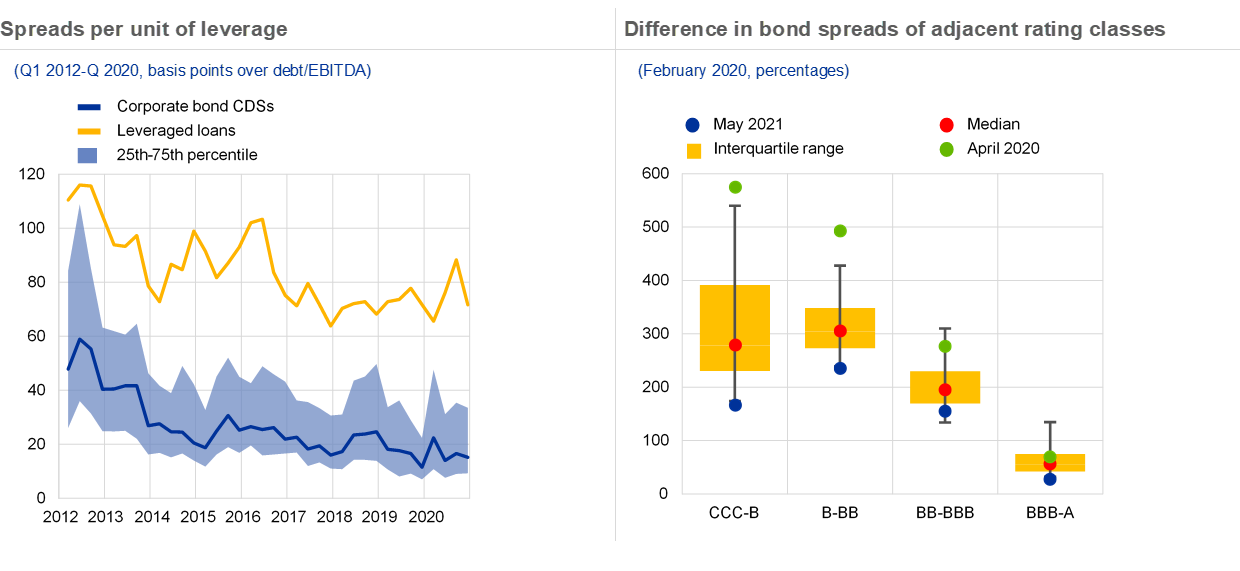

The loosening of underwriting standards has been accompanied by a steady trend of spread compression, with investors willing to accept a progressively lower remuneration for any given level of the borrower’s leverage (Chart 12). The COVID-19 outbreak showed what can happen in the risky credit markets when an exogenous shock suddenly raises uncertainty and dampens investors’ expectations about the performance of corporates and the economy at large. Spreads widened, volatility increased and liquidity dried up as investors fled from the market, with market issuance almost coming to a halt. The subsequent intervention of authorities, unprecedented in terms of magnitude and the array of instruments, managed to quickly calm the turbulence, with spreads and volatility returning to pre-pandemic levels. The latest available evidence points to concerningly low levels of price discrimination in relation to underlying credit quality, with spread differentials for adjacent rating classes of corporate bonds close to historical lows (Chart 12).

Chart 12

Source: ECB.

Notes: In the left-hand panel, units of leverage are based on annualised quarterly earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA). “CDSs” stands for credit default swaps. The right-hand panel shows differences in non-financial corporate spreads between pairs of adjacent rating classes, May 2021 and April 2020 versus historical range.

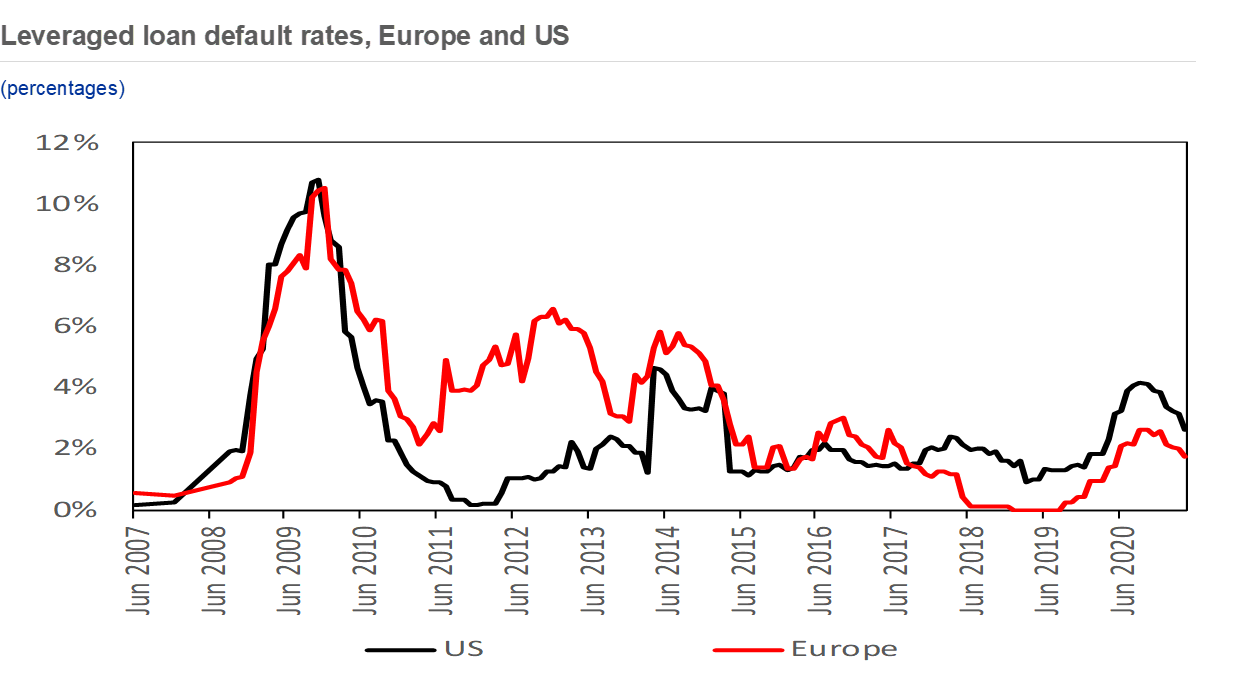

Thanks to the public interventions, leveraged lending defaults have remained below those observed during the great financial crisis (Chart 13). However, underlying credit quality deteriorated and corporate leverage increased in the course of 2020 (Chart 14).

Chart 13

Source: LCD, an offering of S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Chart 14

Sources: Left-hand panel: LCD, an offering of S&P Global Market Intelligence; right-hand panel: ECB Financial Stability Review (2021), May.

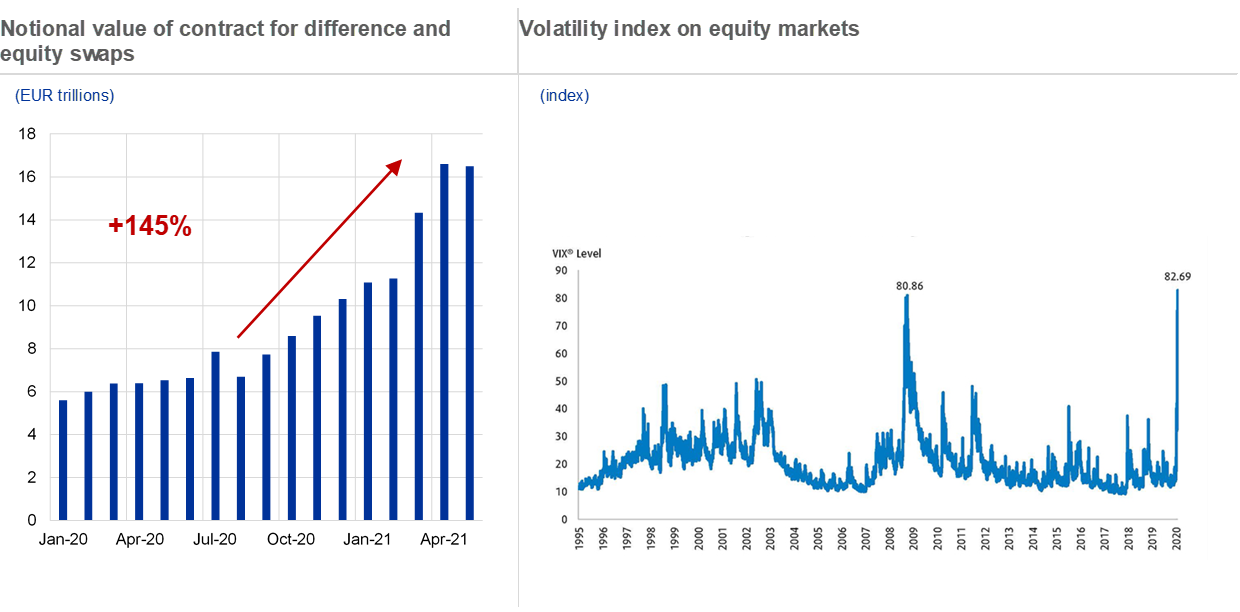

Leverage is not an exclusive feature of the risky credit market. Albeit in different forms, it also manifests itself on the equity market, where market participants across the globe have been increasing their exposure to financial products with intrinsic leverage such as equity derivatives. European Market Infrastructure Regulation data show that, for the euro area, the volume of equity swaps and total return swap contracts for difference reached nearly €15 trillion in the first quarter of 2021 (Chart 15).

In this area, an ecosystem of non-bank financial investors, from hedge funds to family offices, engage in leveraged bets on the performance of individual stocks or baskets of stocks, trade to gain from equity volatility and search for complex yield-enhancing products. Rather worryingly, some investment banking departments, also in Europe, accommodated such trends, without properly mitigating the risks stemming from insufficient transparency of their clients’ investment strategies, including the concentration of positions in single issuers and sectors, overall levels of leverage and the soundness of trades against episodes of extreme volatility.

In the widely discussed case of Archegos, a family office was able to employ a large degree of leverage to take a position on a concentrated portfolio of equities by separately engaging with several prime brokerage banks. The idiosyncratic drop in the price of some of those equities made it impossible for the investor to meet the banks’ margin calls. Suboptimal margining practices employed by some of the prime brokers involved, combined with the downward spiral in stock values that unavoidably result from fire sales, led those brokers to incur substantial losses.

The market dislocation and extreme volatility brought about by the COVID-19 shock (Chart 15) caused material losses on the most complex equity and credit trading portfolio. A powerful indication of the extraordinary nature of the events we witnessed is that an important part of the bank losses that materialised in this area stemmed from the fully unforeseen cancellation of corporate dividend distributions out of the previous year’s earnings. For those European banks whose trading activity was mainly focused on complex equity products, offered to investors in search of above-normal coupons, the events of the first quarter of 2020 resulted in capital market activities falling well short of expectations, leaving deep scars.

Chart 15

Sources: Left-hand panel: ECB; right-hand panel: VIX.

These developments point to growing signs of complacency by market participants, including banks, which have supported higher levels of leverage, financial complexity and opaqueness.

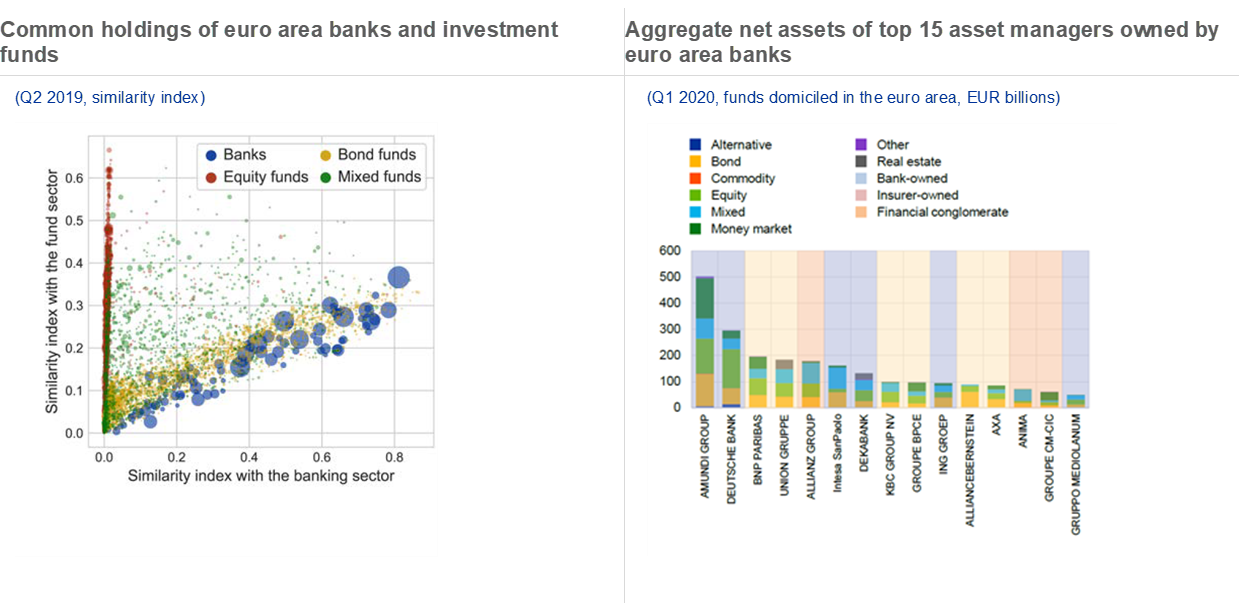

Most importantly, this is happening within financial markets that have grown increasingly interconnected, with banks becoming exposed to the shadow banking sector through a wide array of direct and indirect shock transmission channels. In a recent analysis, the ECB showed that euro area banks’ interconnections with non-bank financial entities include direct exposures (e.g. loans and securities holdings) (Chart 16), overlapping portfolio positions, particularly in the area of debt (as we have discussed in relation to leveraged finance) as well as ownership links, for example through asset management units (Chart 17). We should also acknowledge that, realistically, there are additional channels of indirect exposure that we only have a rough idea about.

All of this makes the banking sector vulnerable to potential new shocks, which we should not necessarily expect to come exclusively from disruptions linked to new COVID-19 infection waves and ensuing spikes in uncertainty originating in the euro area.

A sudden correction in asset prices, hitting the risky segments of the euro area credit market and the equity market that I have discussed with you today, could take place if investors expect inflationary pressures to be persistent and revise their expectations regarding the monetary policy stance. This could trigger a steepening of yield curves in the euro area and, particularly where this is not justified by growth in economic fundamentals, may bring about sensible corrections in the price of risky assets, similar in nature to those that occurred at the outbreak of the pandemic.

Renewed tensions surrounding risky assets would again expose the whole ecosystem of non-bank entities and funds to liquidity risk resulting from investor redemptions as well as credit and valuation losses. The banking sector would suffer direct credit and valuation losses on its direct holdings, but also indirect losses linked to existing exposures vis-à-vis the distressed segment of the funds ecosystem, including counterparty credit risk losses and losses on asset management and other capital market-related business lines owned by banks.

Chart 16

Source: ECB.

Chart 17

Source: ECB.

I have now spent quite a lot of time describing current problems and supervisory concerns. You may wonder at this stage if any policy options are in sight.

With regard to the broader problem of the opaqueness of the shadow banking sector and the degree of interconnectedness in financial markets, I believe it is necessary to revamp the regulatory and supervisory dialogue at the global level, as new solutions might be needed.

However, as I hope I have managed to convey to you today, that broader discussion must not divert our attention away from the key role that banks have constantly played, directly and indirectly, in the build-up of the risks we have discussed.

It is the responsibility of bank boards and senior managers to ensure that institutions can navigate challenging times such as these in a safe and sound manner and without creating the conditions for further turbulence. Strong governance is an essential prerequisite for implementing business model strategies that remain sustainable through the cycle. Robust risk management and risk appetite frameworks at banks should always be key safeguards against the temptations of leverage, complexity and excessive risk-taking.

The lessons learned from previous historical episodes of financial stress, such as the Asian financial crisis, the Long-Term Capital Management failure and the great financial crisis, remain valid today. The sound practices that supervisors and market participants developed in the aftermath of those events need to be followed now more than ever.

As prudential supervisor, the ECB has been stepping up its interaction and supervisory dialogue with the significant institutions that are most active in the markets I mentioned to assess whether banks themselves are taking the appropriate steps to manage their business in a sustainable way through the cycle. Where we see shortcomings, we will take supervisory actions. More specifically, in key areas such as leveraged finance, where previous supervisory guidance has not been sufficiently implemented by banks, we plan to deploy the full range of supervisory tools available to us, including minimum capital requirements commensurate with the specific risk profile of individual banks, should this become necessary.

Conclusions

The worst phase of the COVID-19 pandemic seems to be over and consensus forecasts point to a strong and fast economic rebound. A wide array of indicators show that uncertainty, one of the most damaging features of this recession, is back to manageable levels. Investor and analyst sentiment regarding the role and performance of the banking sector is growing increasingly positive, with some participants arguing that the guard should finally be lowered and precautionary loan loss provisions can be released.

I hope I have convinced you today that, together with uncertainty, public support has been a defining feature of this unique crisis. For the first time in history, as we embark on a recovery, we still don’t see any balance sheet damage left behind. For the economy to withstand the last phase of this crisis and be able to stand on its own two feet as the bulk of the support is withdrawn, we need our banks to remain strongly focused on credit risk management and be duly equipped to deal with the specifics of the present environment. If the guard is lowered too early, a backlog of defaults within vulnerable pockets of the system may hit some of our banks unprepared. Most importantly, the sound risk management practices of our banks are crucial for the ability of the economic system to make the best possible use of available resources along the path to recovery.

As we focus on the direct impact of the pandemic on the creditworthiness of banks’ customers, we should not lose sight of the wider financial environment of muted risk sentiment and the growing signs of market complacency and excessive risk-taking. We should pay close attention to the warning signs of increasing leverage, financial complexity and opacity creating the potential for a dangerous combination of risk factors. Banks are certainly not the only entities behind those trends, but they do appear to be shaping them through their risk management and business strategy choices. Concrete signs of risk build-up have in our view become apparent in the risky asset segments of leveraged debt and equity-related derivatives, which warrant intensified supervision.

As supervisors we will continue to push for strong governance and risk controls, as they are the main safeguards to help us emerge from the pandemic crisis and prevent disruptions in the lending process and new bouts of instability in financial markets.

- Martínez-Miera, D. and Vegas, R. (2021), “Impact of the dividend distribution restriction on the flow of credit to non-financial corporations in Spain”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 1, Banco de España; and European Central Bank (2021) “Evaluating the benefits of euro area dividend distribution recommendations on bank lending and provisioning”, Macroprudential Bulletin, Issue 13, June.

- Balgova, M., Nies, M. and Plekhanov, A. (2016), “The economic impact of reducing non-performing loans”, Working Paper Series, No 193, EBRD.

- Huljak, I., Martin, R., Moccero, D. and Pancaro, C. (2020), “Do non-performing loans matter for bank lending and the business cycle in euro area countries?”, Working Paper Series, No 2411, ECB, May.

- Accornero, M., Alessandri, P., Carpinelli, L. and Sorrentino, A. (2017), “Non-performing loans and the supply of bank credit: evidence from Italy”, Occasional Paper Series, No 374, Banca d’Italia, March.

- Storz, M., Koetter, M., Setzer, R. and Westphal, A. (2017), “Do we want these two to tango? On zombie firms and stressed banks in Europe”, Working Paper Series, No 2104, ECB, October.

- 2018 reference data, see IMF (2019), Global Financial Stability Report.

- Q4 2018 reference data, see Aramonte and Avalos (2019), BIS Quarterly Review.

- European Central Bank (2017), “Guidance on leveraged transactions”, May.

- A widely accepted market standard on the definition of leveraged loan does not exist to date.

Europejski Bank Centralny

Dyrekcja Generalna ds. Komunikacji

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Niemcy

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Przedruk dozwolony pod warunkiem podania źródła.

Kontakt z mediami-

2 July 2021