2020 SREP aggregate results

1 Introduction

1.1 Pragmatic SREP 2020

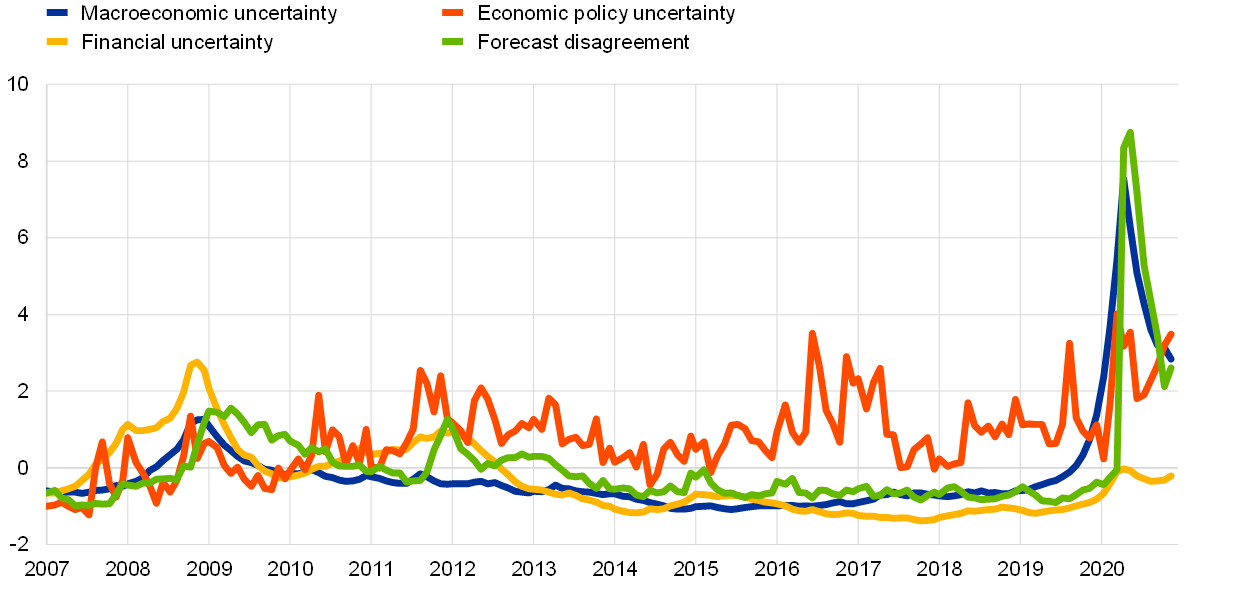

During the coronavirus (COVID‑19) pandemic the overall risk landscape underwent swift and material changes, requiring banks and policymakers to be prepared to respond to rapidly changing circumstances with agility. The pandemic delivered an extraordinary economic shock, causing a drop in GDP projections and creating significant macroeconomic forecasting and other uncertainties.

The outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic and the related containment measures triggered an unprecedented drop in economic activity in 2020[1]. Real GDP in the euro area is projected to return only gradually to its pre-pandemic level by mid‑2022[2].

Chart 1

Real GDP projection and uncertainty

Sources: Top panel: ECB staff macroeconomic projections, December 2020; bottom panel: ECB Economic Bulletin, September 2020.

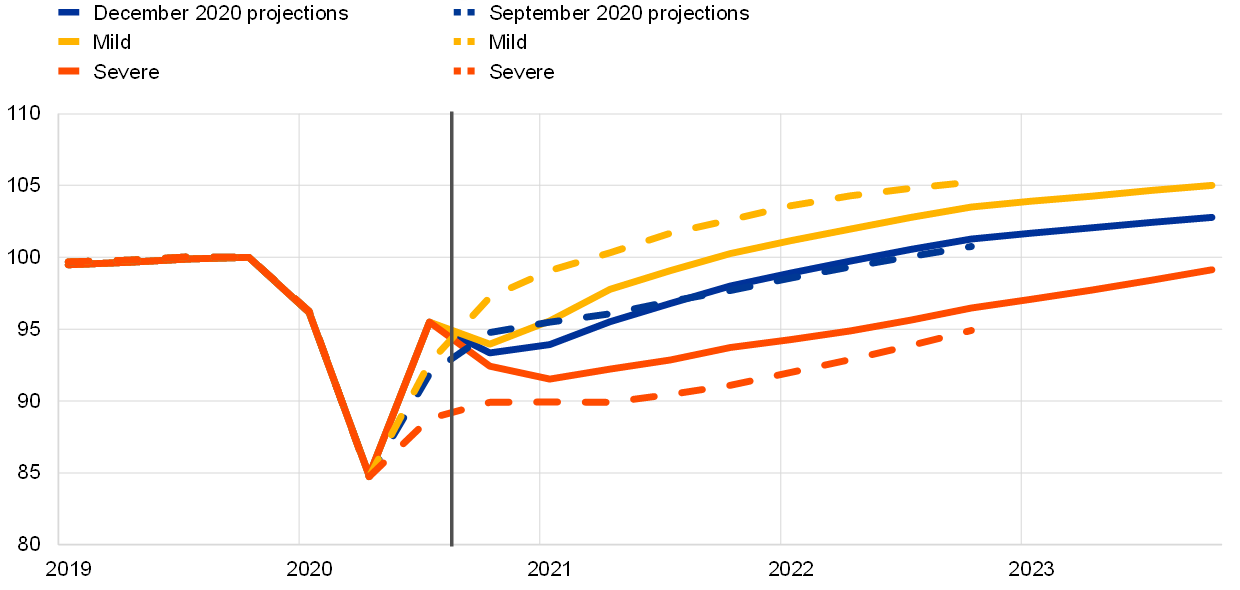

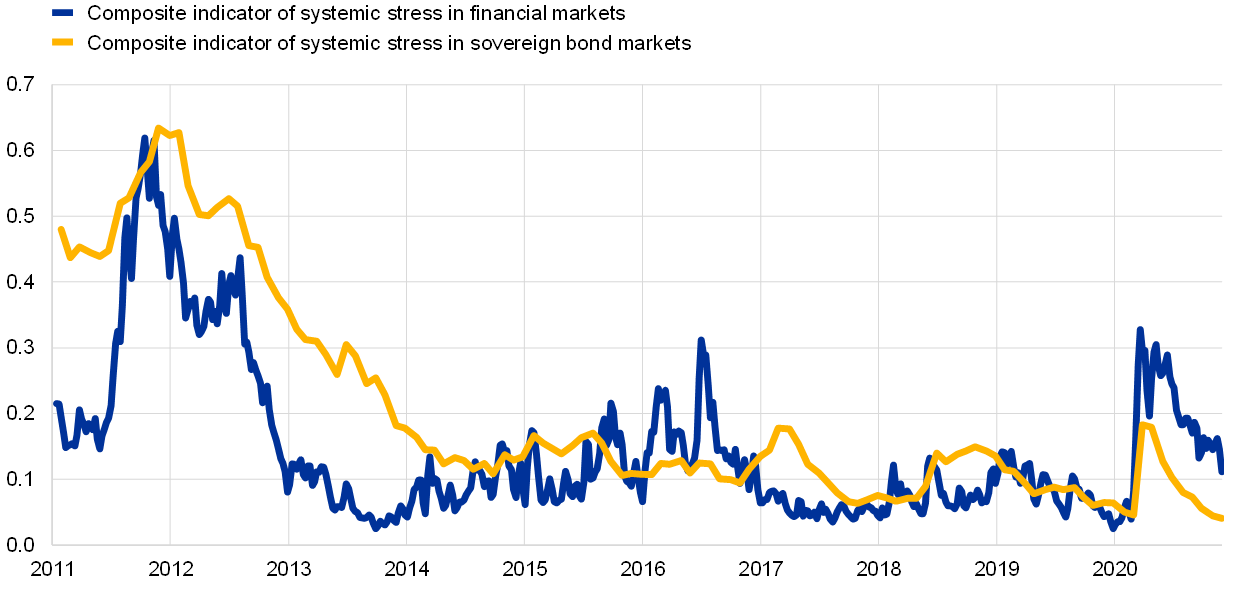

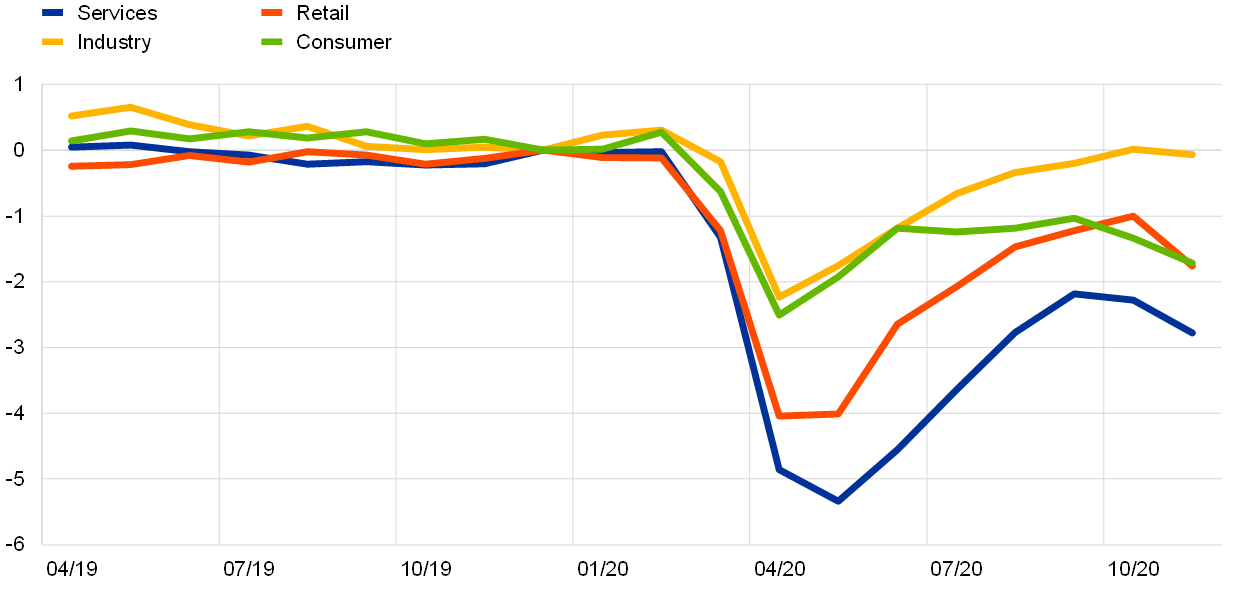

As a direct consequence of the uncertainty, and reflective of the drop in GDP projections, business and consumer confidence deteriorated sharply during the second quarter of 2020. Stress in financial and sovereign markets increased, albeit to a lower extent than during the financial and sovereign debt crises, marking the different nature of the pandemic shock.

Chart 2

Business and consumer confidence by sector and systemic stress

Source: Top panel: ECB Financial Stability Review, November 2020. Bottom panel: ECB Financial Stability Review, May 2020.

Note: Top panel: April 2019 – October 2020, percentage deviation from December 2019 level.

The pandemic forced many businesses, companies, banks and organisations to reprioritise their activities and processes to meet the health and safety measures put in place to manage hospital capacity and save lives. Lockdown measures imposed in many places across Europe made it necessary for the banking industry, as well as other businesses, to implement remote working measures. In March and April in particular, the banking industry was focused on implementing operational contingency plans and creating capacity to continue to serve markets and customers.

Against this exceptional background, ECB Banking Supervision adopted a pragmatic approach towards implementing its annual core activity – the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP), also in line with the European Banking Authority (EBA) guidelines[3]. The main features of the ECB pragmatic SREP 2020 include the following:

- focusing on how banks are handling the challenges and risks to capital and liquidity arising from the ongoing crisis;

- keeping Pillar 2 requirements (P2R) stable, unless changes are justified by exceptional circumstances affecting an individual bank;

- keeping Pillar 2 guidance (P2G) stable, reflecting the postponement of the EBA stress test exercise;

- no updating of SREP scores, unless justified by exceptional circumstances affecting an individual bank;

- addressing supervisory concerns mainly via qualitative recommendations;

- following a pragmatic approach to collecting information on the ICAAP and the ILAAP.

1.2 ECB relief measures

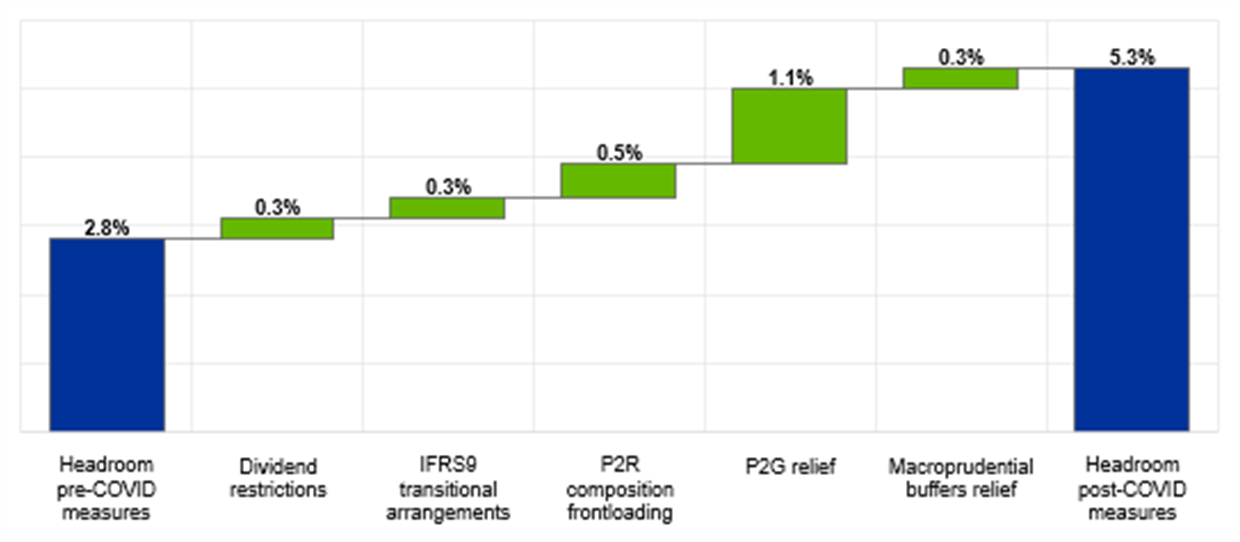

In addition to adopting a pragmatic approach to the SREP, ECB Banking Supervision also implemented a number of relief measures during the first quarter of 2020 to ensure that its directly supervised institutions (SIs) could continue to serve the economy and address potential risks arising from the COVID‑19 pandemic. These measures remain in place at the time of writing. In particular:

- Capital – allowing banks to:

- operate temporarily below the level of Pillar 2 Guidance (P2G) until at least end‑2022 and below their capital conservation buffer;

- use capital instruments that do not qualify as Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital to meet the Pillar 2 Requirements (P2R), frontloading the new rules originally scheduled to come into force with Capital Requirements Directive V (CRD V).

- Credit risk – delivering guidance to banks to:

- provide further flexibility in prudential treatment of loans backed by public support measures;

- apply the transitional IFRS 9 provisions foreseen in the CRR and avoid excessively procyclical assumptions in the IFRS 9 models used to determine their provisions;

- clarify ECB Banking Supervision’s operational expectations regarding the management of the quality of loan portfolios, so that SIs could take timely action to minimise any cliff effects with a clear understanding of the risks they were facing, thus enabling them to devise appropriate strategies.

- Liquidity – allowing banks to operate temporarily below the 100% liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) requirement until at least end‑2021.

- Operational aspects – rescheduling on-site inspections and extending deadlines for remedial actions arising from recent on-site inspections and internal model investigations, while ensuring the overall prudential soundness of SIs.

- Qualitative requirements – extending the deadline for complying with the SREP 2019 qualitative measures by six months.

In March 2020, the ECB also recommended banks not to pay dividends or conduct share buy-backs in response to the pandemic. The ECB recommended banks to preserve capital in order to be able to support households, small businesses and corporate borrowers and/or to absorb losses on existing exposures to such borrowers. The recommendation was first extended in July 2020 until the end of 2020. In its revised December 2020 recommendation, the ECB asked banks to refrain from or limit dividends until 30 September 2021. Dividends should remain below 15% of cumulated 2019‑20 profits and not higher than 20 basis points of CET1 ratio. The ECB also recommended banks to adopt an extremely moderate approach towards variable remuneration payments.

1.3 Overall resilience of the banking sector

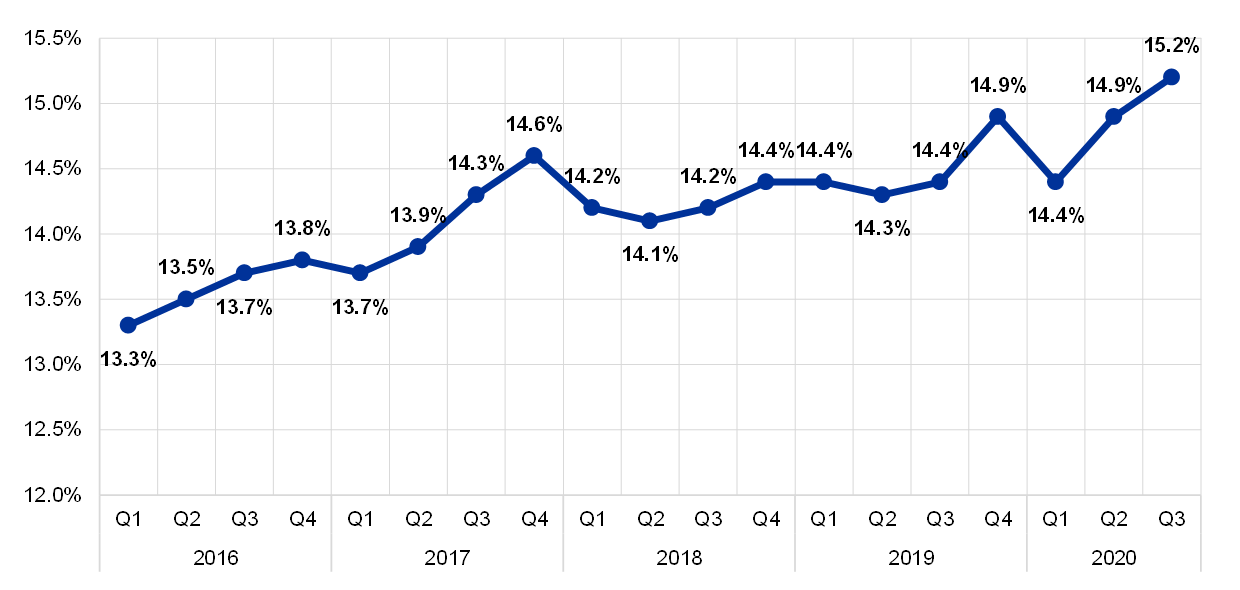

Euro area banks entered 2020 with significantly higher capital levels and far greater resilience to withstand the changing landscape than was the case at the time of the Great Financial Crisis. In December 2019 the CET1 ratio of institutions directly supervised by the ECB stood at 14.9%.

Chart 3

Quarterly developments of CET1 ratio

Source: ECB supervisory statistics.

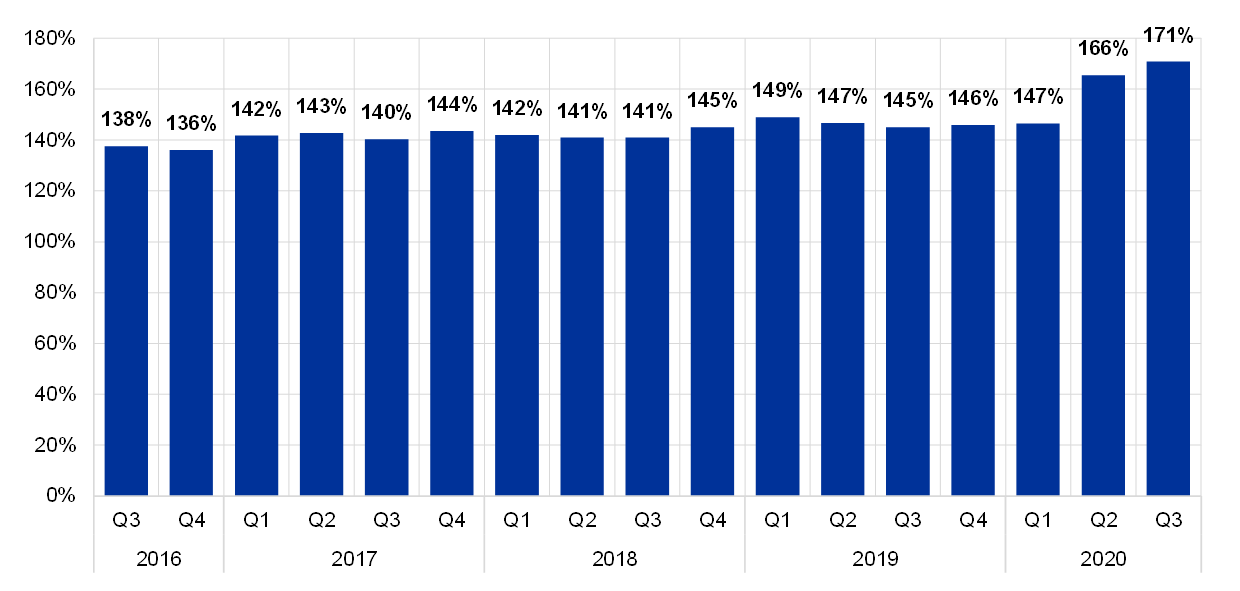

Chart 4

Quarterly developments of liquidity coverage ratio (LCR)

Source: ECB supervisory statistics.

Coordinated policy measures in the form of fiscal public support measures, monetary policy interventions (especially asset purchase programs and liquidity operations), public loan guarantees and moratoria as well as unprecedented levels of supervisory flexibility, all intended to deliver support to the overall economy, provided significant protection to households and businesses as well as the banking sector.

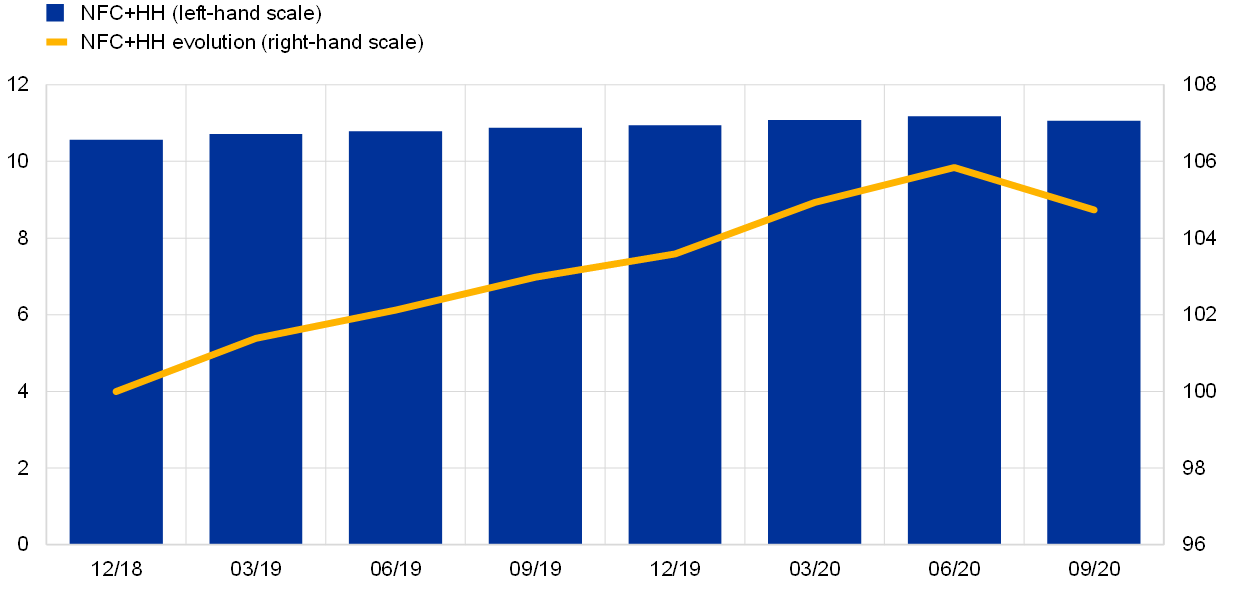

Thus far, excessive procyclicality from the shock has been averted, with overall lending dynamics showing resilience throughout 2020. However, the year-end outlook is less favourable, with lending dynamics expected to worsen in the short and medium term.

Chart 5

Developments in lending dynamics from 2018 to Q3 2020

(left-hand scale: EUR billions; right-hand scale: index, December 2018 = 100)

Sources: FINREP and ECB calculations based on data as at Q3 2020.

Ample capital buffers remained available as of Q3 2020, partly thanks to the various capital relief measures taken by the ECB and macroprudential authorities (see previous section). Capital buffers can be tapped for any necessary loss absorption as public support measures are withdrawn when the pandemic recedes and for lending to the economy.

Chart 6

Aggregate capital headroom as at September 2020

Sources: FINREP and ECB calculations based on data as at Q3 2020.

In the coming months, increasing infection rates and episodic lockdowns threaten to dampen economic activities across the euro area while at the same time, vaccinations hold the prospect of a return to more usual economic activity as swaths of the population are immunised. The speed of the recovery will depend on the evolution of the pandemic, the duration of containment measures, the potential phase-out of policy support measures as well as the successful implementation and distribution of effective medical solutions.

Significant uncertainties remain in the short to medium term and the SREP data indicates an ongoing need for vigilance and continued supervisory challenge in several critical areas.

2 Capital requirements and guidance

2.1 Key messages

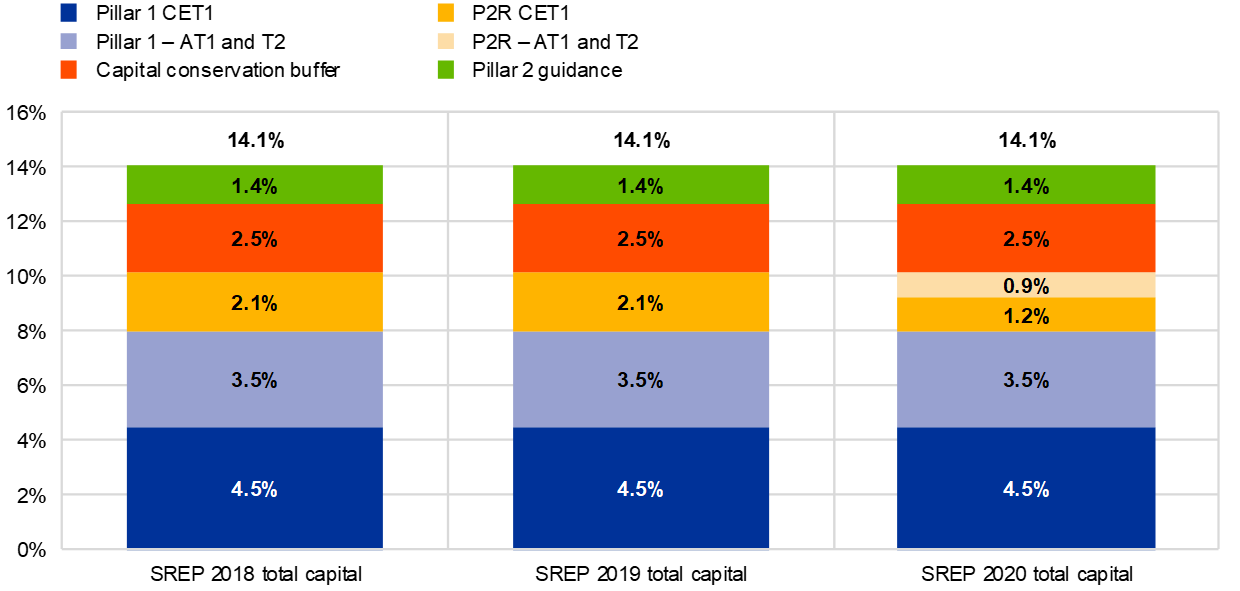

The ECB’s SREP pragmatic approach set the SREP requirements and guidance in total capital (excluding systemic buffers and the countercyclical capital buffer) for the 2020 cycle to remain consistent with the 2019 cycle, standing at around 14% on average.

The P2R was also kept stable at around 2.1% for the SREP 2020, except for a few exceptional cases such as those of new banks subject to direct supervision of the ECB, for which a new P2R applicable in 2021 has been disclosed on the following dedicated webpage. However, the P2R CET1 component decreased to 1.2% owing to the frontloading of CRD V on the P2R composition[4], as part of the COVID‑19 capital relief measures.

The P2G, which captures supervisory risk concerns arising from the stress test outcomes, was also kept unchanged at approximately 1.4% for the SREP 2020 owing to the postponement of the stress tests to 2021.

Chart 7

SREP capital requirements and guidance (excluding systemic buffers and countercyclical capital buffer) in total capital

Sources: SREP 2020 values based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021. SREP 2019 values based on 109 SREP 2019 decisions finalised as at 31 December 2019 and applicable from 1 January 2021. SREP 2018 values based on 107 SREP 2018 decisions finalised as at 31 January 2019 and presented in the SSM SREP Methodology Booklet – 2018 edition.

Notes: “Total SREP capital requirements and guidance” refers to: 8% Pillar 1 + Pillar 2 requirement in total capital + Capital conservation buffer + Pillar 2 guidance. It excludes systemic buffers (G‑SII, O‑SII and systemic risk buffer) and the countercyclical capital buffer as these are independent from the SREP assessment.

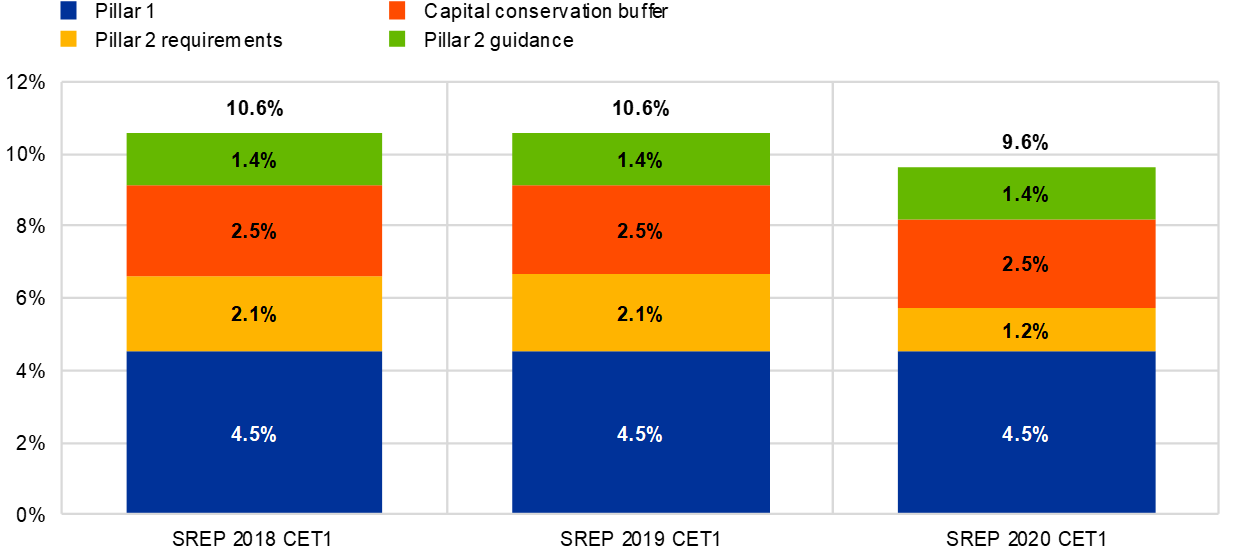

The CET1 component of the SREP requirements and guidance (excluding systemic buffers and the countercyclical capital buffer) for the 2020 cycle decreased from around 10.6% to 9.6%[5] due to the frontloading of the revised rules on the P2R capital composition.[6]

Chart 8

SREP requirements and guidance (excluding systemic buffers and countercyclical capital buffer) in CET1

Sources: SREP 2020 values based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021. SREP 2019 values based on 109 SREP 2019 decisions finalised as at 31 December 2019 and applicable from 1 January 2020. SREP 2018 values based on 107 SREP 2018 decisions finalised as at 31 January 2019 and presented in the SSM SREP Methodology Booklet – 2018 edition.

Notes: “CET1 SREP requirements and guidance” refers to: Pillar 1 in CET1 + Pillar 2 requirement in CET1 + Capital conservation buffer + Pillar 2 guidance. It excludes systemic buffers (G‑SII, O‑SII and systemic risk buffer) and the countercyclical capital buffer as these are independent from the SREP assessment. Under Capital Requirements Directive V (CRD V), which came into effect on 1 January 2021, the P2R should have the same capital composition as that of Pillar 1. Therefore, P2R should be held with 56.25% in CET1 and 75% in Tier 1 as a minimum requirement.

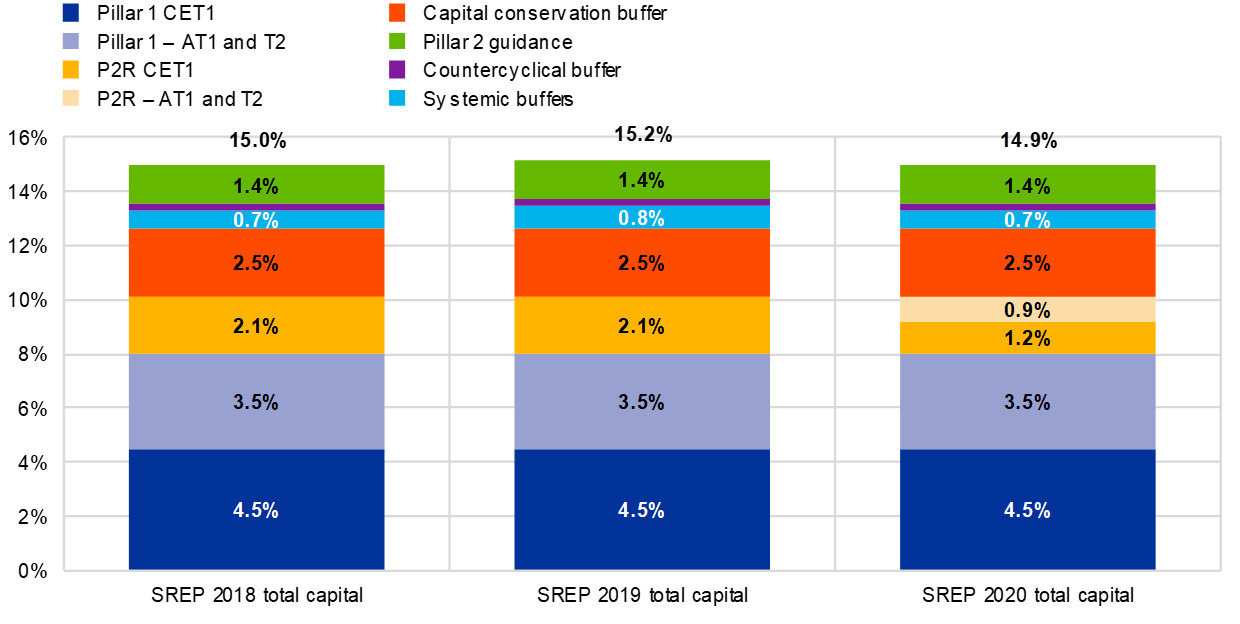

Including systemic buffers and the countercyclical capital buffer (0.9% on average), the overall capital requirement (OCR) and guidance for the 2020 cycle slightly decreased by around 30 basis points, mainly due to a decision by the national macroprudential authorities to relax the countercyclical capital buffer requirement.

Chart 9

Overall capital requirements and guidance

Sources: SREP 2020 values based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021. SREP 2019 values based on 109 SREP 2019 decisions finalised as at 31 December 2019 and applicable from 1 January 2020. SREP 2018 values based on 107 SREP 2018 decisions finalised as at 31 January 2019 and presented in the SSM SREP Methodology Booklet – 2018 edition.

Notes: Overall capital requirements include 8% Pillar 1 + Pillar 2 requirement in total capital + Capital conservation buffer + Systemic buffers and the countercyclical capital buffer. Pillar 2 guidance is added on top of overall capital requirements (OCR).

3 Qualitative measures and recommendations

3.1 Key messages

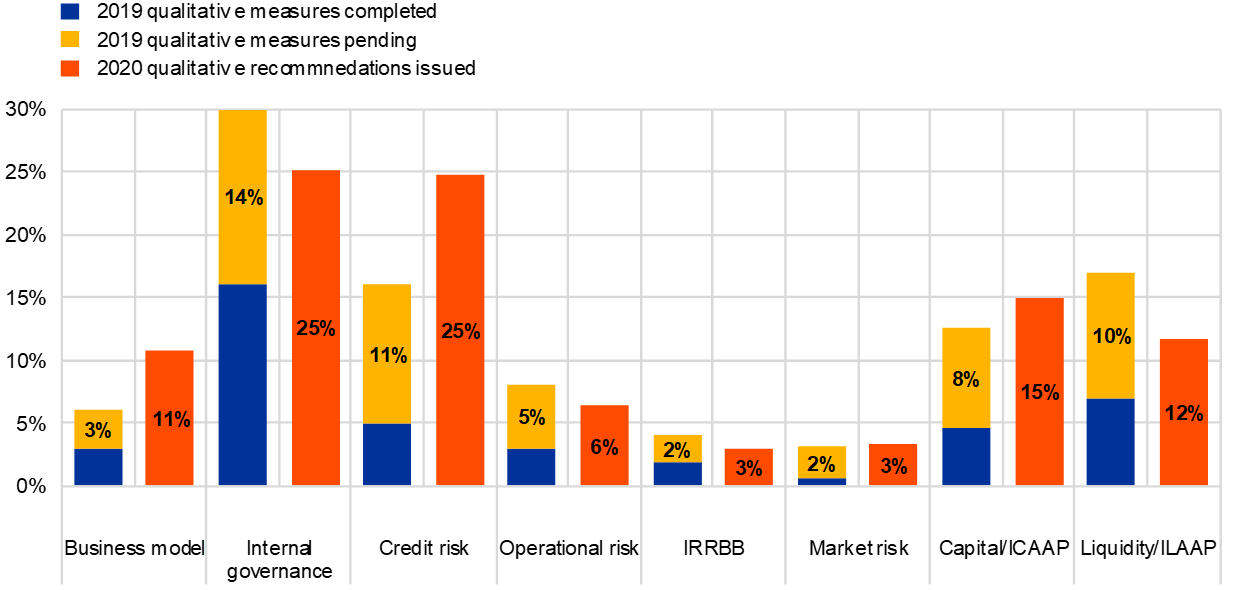

Qualitative recommendations were addressed to all SREP SIs[7] in 2020 as a result of the Joint Supervisory Teams’ (JST) findings (by comparison, qualitative measures were applied to 83%[8] of SIs in 2019). Most of the qualitative recommendations addressed to banks by the JSTs concerned the adequacy of their processes under crisis conditions, in line with the specific COVID‑19 focus of the SREP 2020.

Particularly due to the ECB relief measures to extend the deadline for complying with the SREP 2019 qualitative measures by six months, a significant number of findings addressed via qualitative measures remain outstanding and unmitigated from previous years.

Compared with the previous SREP cycle (in 2019):

- Findings on credit risk increased significantly (+79% compared with the previous year). Credit risk recommendations were issued for 80% of SIs, the largest share across the various risk profiles (47% of SIs in 2019). Overall, recommendations were more severe, reflecting heightened supervisory scrutiny into credit risk management practices.

- Findings on the business model element also increased significantly (+105% compared with last year).

- Findings related to capital (+11%) and internal governance (-1%) were broadly stable, although the internal governance-related findings continue to be the most numerous in absolute numbers in 2020. Moreover, a significant number (46%) of findings on governance addressed via qualitative measures remain outstanding from the previous year.

- Findings on liquidity risk decreased significantly (-20%). Findings largely referred to ILAAP (e.g. supervisors sought improvements in banks’ ILAAPs) and were of an overall lower intensity with respect to previous years.

Chart 10

Qualitative measures* in 2019 vs qualitative recommendations in 2020

Sources: SREP 2020 values based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021. SREP 2019 values based on 109 SREP 2019 decisions finalised as at 31 December 2019 and applicable from 1 January 2020.

Notes: The chart overview does not include weaknesses which may have already been addressed by supervisory actions other than the qualitative measures and/or recommendations addressed to banks in the context of the SREP 2020. * In the context of the COVID‑19 pandemic, on 27 March 2020 the ECB Supervisory Board decided to take a pragmatic approach to the SREP 2020. As a result, and with a view to providing capital relief and supporting banks, the qualitative measures were formally replaced by qualitative recommendations in order to address supervisory concerns, unless justified by exceptional circumstances affecting an individual institution. Moreover, 2019 qualitative measures are considered outstanding mainly due to the ECB decision to extend the deadline for complying with the SREP 2019 qualitative measures by six months.

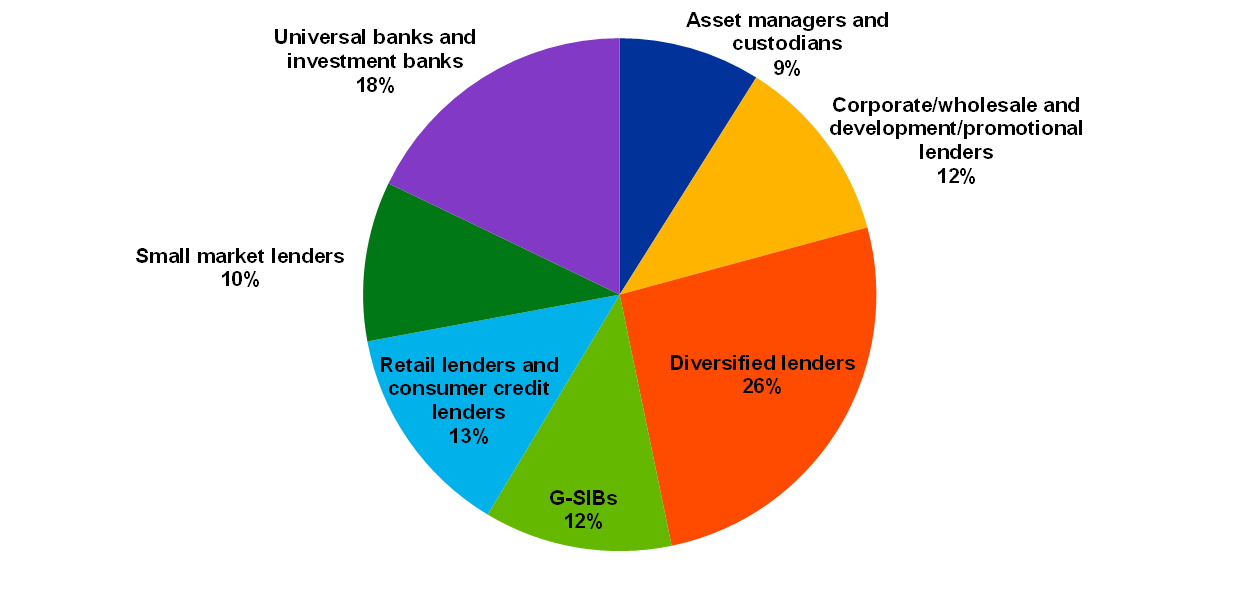

3.2 Breakdown by business model

The following chart shows the breakdown of SREP 2020 recommendations by business model. Other remedial actions not included in the chart below may also have been addressed/recommended to SIs in the course of 2020 as the outcome of on-site inspections or other supervisory activities.

Diversified lenders and universal banks show the highest proportion of qualitative recommendations, with more than half issued in the areas of internal governance and credit risk.

Chart 11

Qualitative recommendations with breakdown by business model

Source: SREP 2020 values based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021.

Note: The chart overview does not include weaknesses which may have already been addressed by supervisory actions other than the qualitative measures and/or recommendations addressed to banks in the context of the SREP 2020.

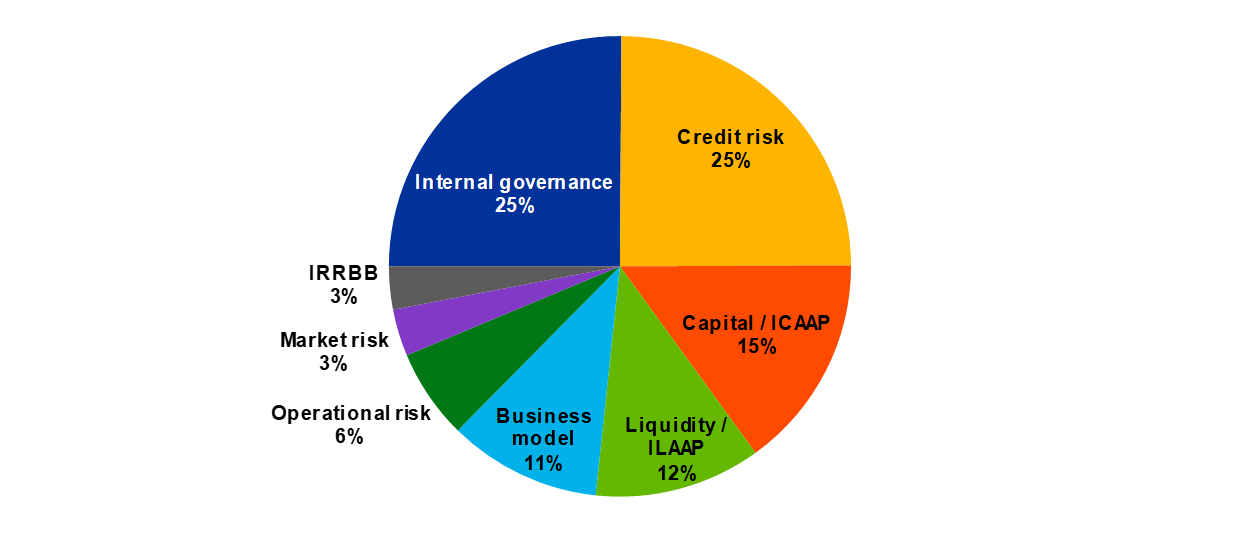

3.3 Breakdown by main risk area

Qualitative recommendations in the SREP 2020 cycle were mainly related to internal governance (in particular the internal control function), credit risk (in particular monitoring and reporting) and capital (in particular the capital planning process and the stress testing framework for the ICAAPs).

For further information on qualitative recommendations in the areas of business model, governance, credit risk and capital/ICAAP risk profiles, please refer to the specific section on risk in this document.

Chart 12

Qualitative recommendations with breakdown by main SREP risk area

Source: SREP 2020 values based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021.

Note: The chart overview does not include weaknesses which may have already been addressed by supervisory actions other than the qualitative measures and/or recommendations addressed to banks in the context of the SREP 2020.

4 Deep dive on main risks

This chapter is organised into five sections that focus on the main risks identified in the SREP 2020. These sections are based on the main elements of the SREP 2020, and are also presented on the SREP methodology webpage, as follows:

- business model (Element 1);

- internal governance (Element 2);

- credit risk (Element 3);

- capital adequacy (Element 3); and

- banks’ operational resilience during the pandemic, including in relation to anti-money laundering.

Liquidity risk (Element 4) has not been discussed or examined in as much detail in this document given the limited supervisory concerns during the SREP 2020.

Each section provides an overview of the main challenges faced by the SIs in the context of the COVID‑19 pandemic and discusses the supervisory concerns and recommendations communicated to banks.

4.1 Element 1: Business model

4.1.1 Key messages

Profitability dropped in 2020, mainly due to higher impairment flows, lower net interest income and a decline in fees and commissions. However, banks expect profitability to gradually recover from 2021 onwards.

Decreasing margins intensified the pressure on banks to adjust their cost bases, leading to a number of cost-cutting measures over the course of 2020, such as branch consolidation, innovation projects and remote working arrangements. Banks were still able to serve their customers during the lockdown periods, also thanks to customers’ increased acceptance of digital over physical services.

Recent events have pushed the trend towards the digitalisation of internal processes, even though one out of four banks is still facing delays in delivering on digitalisation initiatives.

Banks have also responded to the challenges posed by the crisis by pursuing broader strategic overhauls or restructuring plans as well as domestic consolidation operations. Supervisors have been encouraging banks to pursue such strategic overhauls and are closely monitoring the implementation of banks’ strategic actions. Moreover, a guide on consolidation in the banking sector was recently issued in order to give certainty and facilitate sound consolidation processes.

Supervisors have expressed concerns about the reliability of business plans for some banks and have addressed them via qualitative recommendations on short-term profitability, e.g. requests to update profitability forecasts, to initiate strategy reviews and to provide supervisors with detailed implementation plans and monitoring information.

4.1.2 Focus on profitability

The cyclical challenges arising from the COVID‑19 crisis affected banks primarily through increased provisioning needs, but the pandemic also adversely impacted banks’ income-generating capacity and weighed further on the already low revenue levels of the SIs:

- Impairment flows in the first half of 2020 increased by 150% compared with the first half of 2019.

- Interest income remained under pressure and the effects of loan moratoria and lower lending rates fuelled by the lower-for-longer interest rate environment, reduced interest rate margins.

- At the same time, fees and commissions declined significantly in the first half of 2020 across many segments, with the exception of securities business.

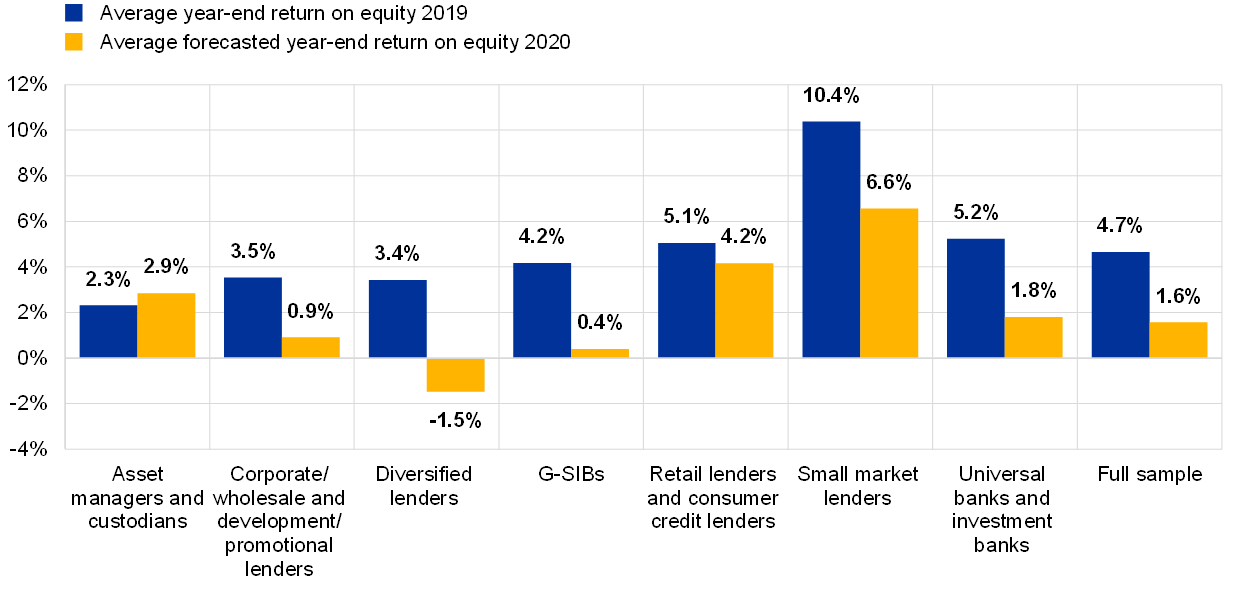

These effects brought the return on equity (ROE) of SIs close to zero in the first half of 2020 and banks expected an overall sharp deterioration in the year-end 2020 ROE (1.6% on average) as compared with 2019 (4.7% on average).

Diversified lenders were the most negatively affected business model with negative return on equity expected for the end of 2020, while corporate, wholesale and development lenders showed a lower degree of revenue diversification and a specific concentration in vulnerable sectors (e.g. shipping).

Difficulties at universal banks were mainly related to idiosyncratic and/or legacy issues whereas those at investment banks were generated by cross-subsidisation to parents outside the banking union.

Small market lenders remained the most profitable group, although they also experienced a significant decline in profitability.

Chart 13

Year-end ROE 2019 vs forecasted year-end ROE 2020 with breakdown by business model

Sources: FINREP, banks’ own estimates of year-end projections as reported in the COVID‑19 reporting exercise as at Q3 2020.

Note: The sample is made up of 109 SIs for which a SREP 2020 assessment was conducted and data are available.

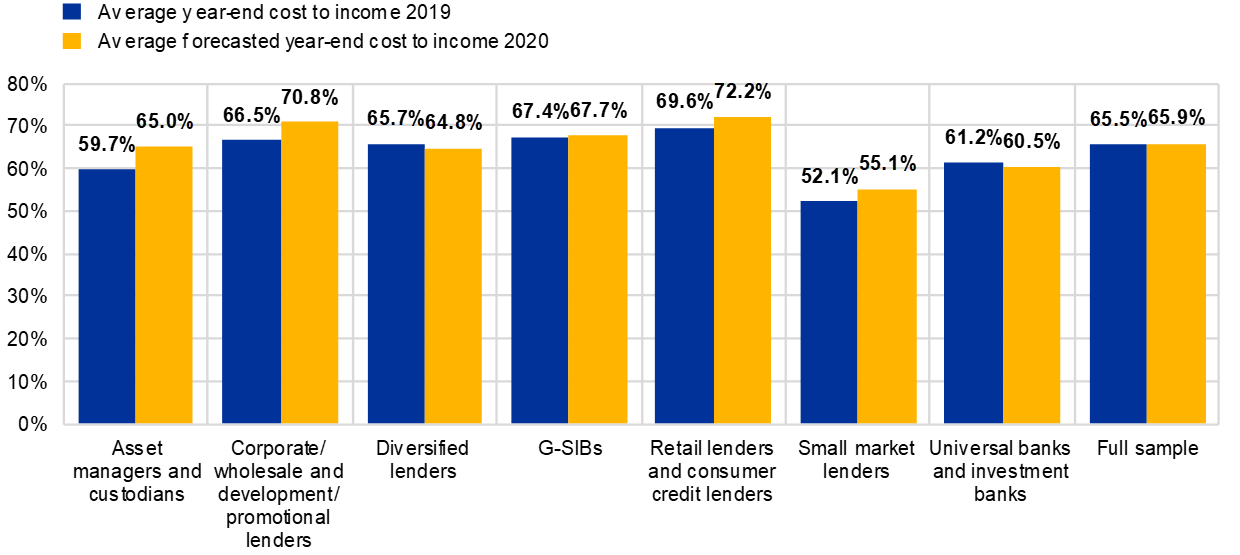

4.1.3 Focus on structural issues

Structural issues remain one of the key supervisory concerns for the European banking sector. Despite a moderate decrease in the cost base (aggregate costs are down by around 1.9% in 2020), declining revenues (aggregate operating income are down by around 3% in 2020) led to a moderate increase in cost-to-income ratios, on average of around 2%, from 2019 to the 2020 year-end projections.

Retail and small market lenders reported the highest increase (around 9% more as compared with 2019) in their cost-to-income ratios, whereas small market lenders retained the most efficient cost structure.

Diversified lenders reported a slight improvement in their cost structures. Stable cost-to-income ratios mask challenges for corporate and wholesale lenders, which were negatively affected by a fall in revenues.

Chart 14

2019 year-end cost-to-income ratio vs forecasted 2020 year-end cost-to-income ratio with breakdown by business model

Sources: FINREP, banks’ own estimates of year-end projections as reported in the COVID‑19 reporting exercise as at Q3 2020.

Notes: Averages by business model are weighted by total operating income. The sample is made up of 111 SIs for which a SREP 2020 assessment was conducted and data are available.

4.1.4 Focus on transformation plans digitalisation

JSTs noted significant efforts by banks to refine their business models, with approximately 70% of SIs taking action to press ahead with their transformation plans as a consequence of COVID‑19. Actions undertaken include:

- investments in digital and direct banking services (instant payments; customisation of services/products; constant assistance; improvement in mobile banking design/interface and digital onboarding; financial advisory, etc.);

- digitalisation of internal processes (data monitoring; investments in artificial intelligence; creation of new digital platforms; automation of existing processes);

- cost-cutting measures (acceleration of branch consolidation and innovation projects; business restructuring plans and cost-saving measures in relation to travel expenses; remote working arrangements; staff reduction/relocation and outsourcing).

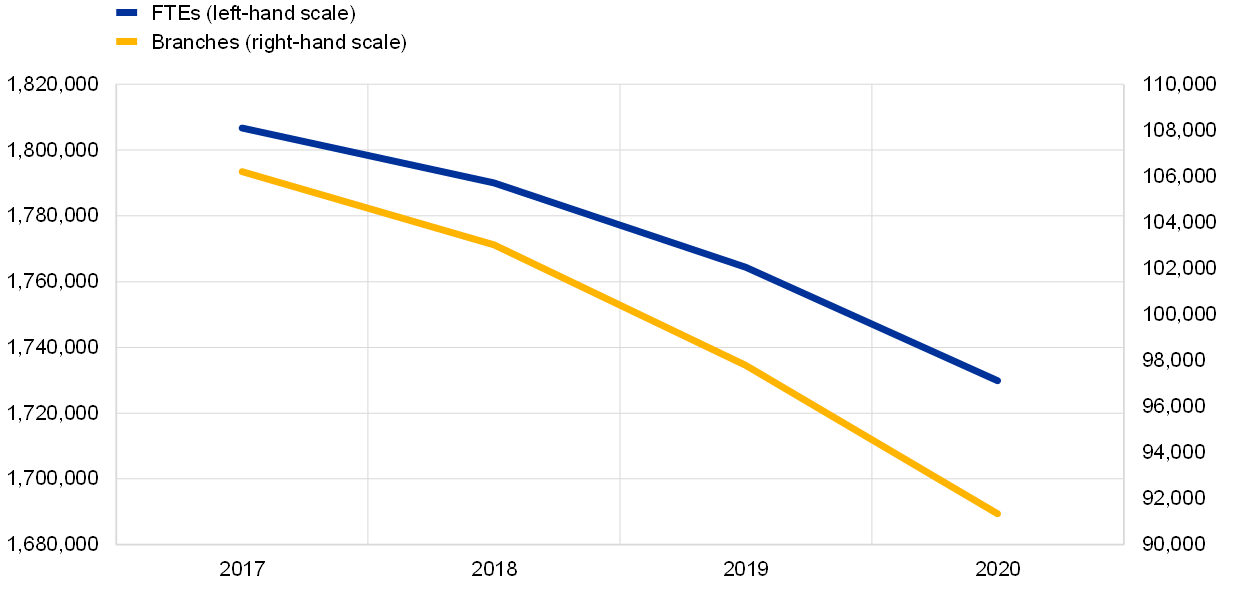

The continued decrease in full-time employees (FTEs) and branches is also reflected in a reduction in operating expenses.

Chart 15

Evolution of branches and full-time employees from 2017 to 2020

Source: Banks’ own estimates of year-end projections as reported in the COVID‑19 reporting exercise as at Q3 2020.

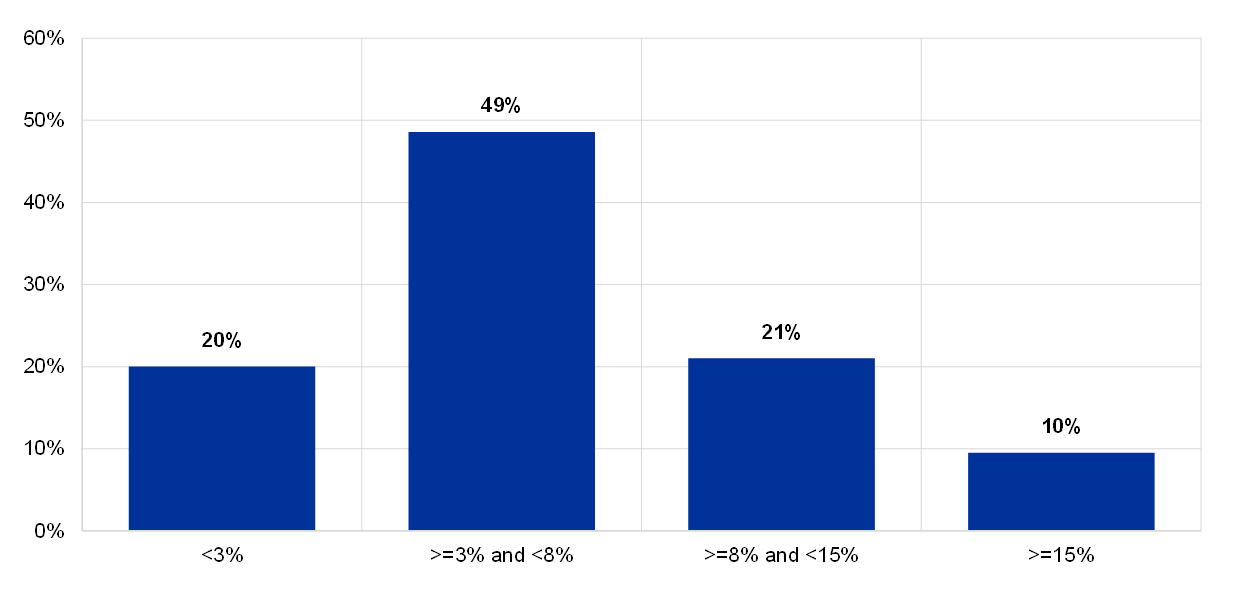

JSTs are closely scrutinising IT investment plans, whose costs appear to be on the low side for a number of banks (approximately one in five banks spent less than 3% of their total operating income on IT costs in the first three quarters of 2020).

Chart 16

Distribution of IT costs as a share of total operating income

Sources: COREP and FINREP data with reference date Q3 2020.

Note: y-axis indicates the % of SIs out of the full sample, which is made up of 105 SIs for which a SREP 2020 assessment was conducted and data are available.

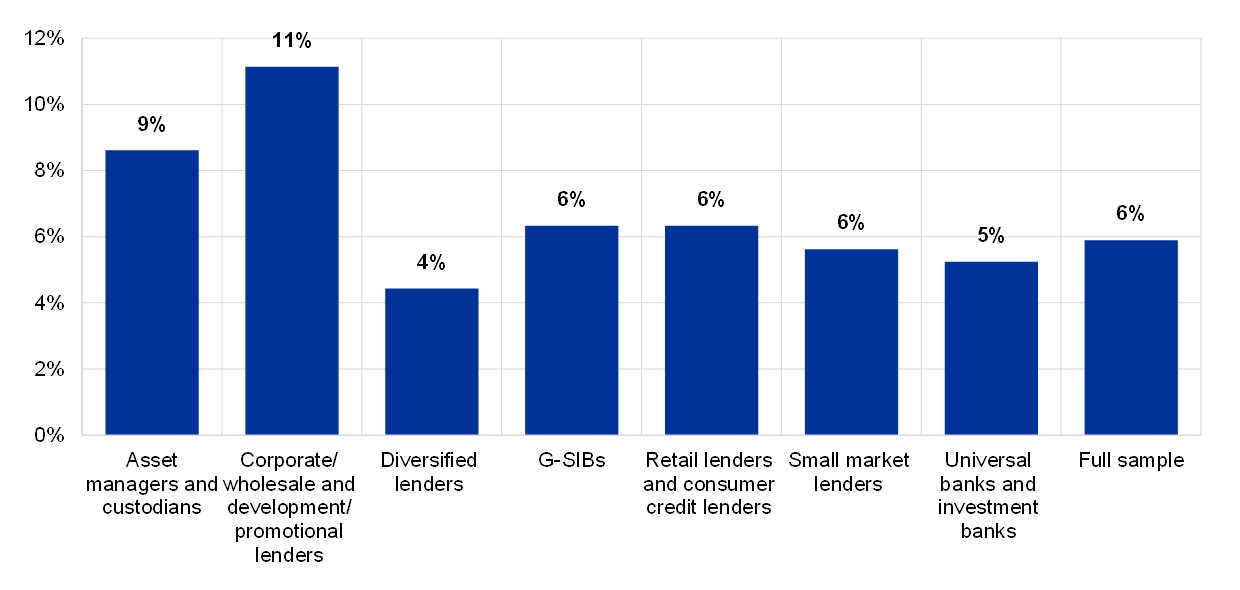

Corporate and wholesale lenders, custodians and asset managers spent the highest average share of their operating income on IT costs, while the lowest share is recorded by diversified lenders, universal and investment banks.

Chart 17

IT costs over total operating income, with breakdown by business model

Sources: COREP and FINREP data with reference date Q3 2020.

Notes: Averages by business model are weighted by total operating income. The sample is made up of 105 SIs for which a SREP 2020 assessment was conducted and data are available.

4.1.5 Supervisory expectations

Despite the drop in profitability in the course of 2020, banks project a gradual recovery in profitability from 2021 onwards.

Supervisors challenged the projected rebound in profitability in relation to the potential for an adverse impact on provisions once the public support measures have ceased (i.e. cliff effects), as well as over the broader impact on credit quality as a result of the 2020 recession and the pressure on net interest income, which is likely to push revenues down in the medium term.

JSTs also addressed pre-COVID‑19 existing business model weaknesses and strategic uncertainties, for example, in relation to delays in the implementation of strategies and the need for further strategic transformations, as well as to specific needs for adjusting business models focused on sectors vulnerable to the impact of COVID‑19, which are likely to be particularly prone to long-term challenges.

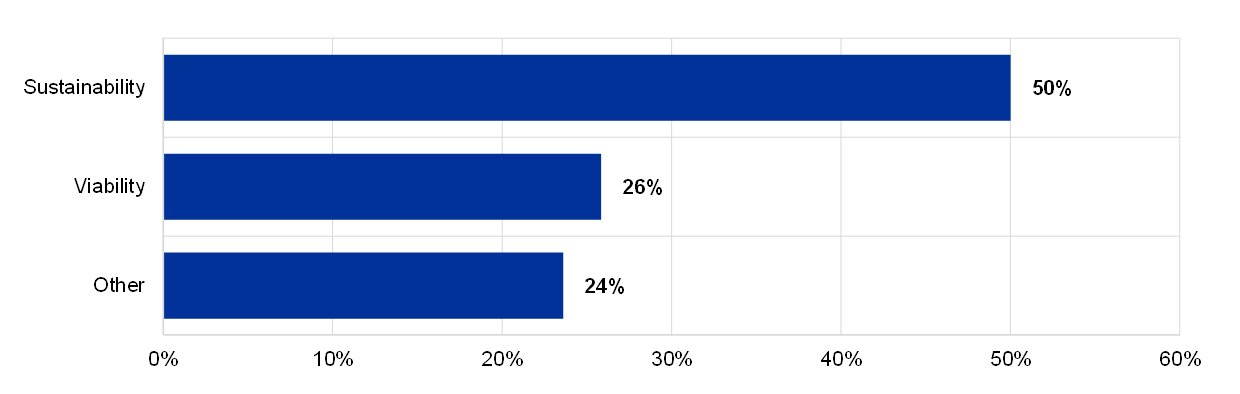

Medium- and long-term profitability challenges is the sub-category most affected, with half of the recommendations being addressed in the area of business model sustainability (50%).

Chart 18

Breakdown of business model-related qualitative recommendations

Source: SREP 2020 values based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021.

Notes: The chart overview does not include weaknesses which may have already been addressed by supervisory actions other than the qualitative measures and/or recommendations addressed to banks in the context of the SREP 2020. Sustainability refers to medium- and long-term profitability, usually requiring updates of forecasts, strategic plans and financial projections, whereas viability refers to short-term profitability and identified weaknesses requiring rapid correction by banks. The “Other” category refers to other aspects, such as delays and/or postponement of projects or transformation plans; management reporting; planning and processes; pricing; booking models and other policies; cost-cutting measures; digitalisation; COVID‑19 impact on the market and competitive environment or on anti-money laundering.

4.2 Element 2: Internal governance and risk management

4.2.1 Key messages

Overall, banks managed to adapt their governance arrangements to adequately manage and monitor risks stemming from the COVID‑19 crisis[9]. For example, JSTs assessed positively the capacity to set up effective crisis committees in response to the pandemic.

Nonetheless, some banks were slow to address COVID‑19 governance challenges in relation to:

- lack of adequate involvement of the management body and insufficient follow-up and oversight of business functions, in particular related to reporting adequacy;

- issues regarding credit risk management identified also within the internal control functions;

- sustained structural weaknesses in the area of risk data aggregation and reporting, which were further exacerbated by the pandemic.

4.2.2 Focus on management body and internal control functions

The management body’s reaction to the crisis was broadly adequate in most cases. However, decision-making capabilities were hampered in some banks, primarily as a result of:

- inadequate reporting to the management body owing to timing and/or data quality issues, i.e. sustained shortcomings in terms of risk data aggregation and reporting;

- lack of involvement of the management body, as well as insufficient follow-up and oversight of bottom-up decisions relating to the crisis.

Issues relating to internal control functions date back to previous findings (e.g. structural understaffing, inadequate tooling and insufficient steering capacity of group structures vis-à-vis subsidiaries), with COVID‑19‑related issues also apparent in some banks.

- Detrimental impact of inappropriate internal control functions identified in credit risk management. For example, credit risk identification and/or monitoring; challenging capacity issues and organisational structure for the three lines of defence; lack of staffing for the first line of defence and lack of digitalisation of credit files.

- Lack of participation by internal control functions in crisis management, namely the Internal Audit and Compliance functions are not adequately involved in crisis committees.

4.2.3 Focus on risk data aggregation and reporting

Around 70% of JSTs identified risk data aggregation and reporting concerns with different levels of severity. Issues included difficulties addressing standard and ad hoc information needs in a timely manner, low capacity for aggregating data at group level driven by different systems at subsidiary level, and weak IT infrastructures and risk data architecture.

Data aggregation problems seemed sustained and structural; indeed, they have been under supervisory focus for the past few years. Banks for which JSTs had expressed serious concerns in 2020 had already undergone, in the past two years, a SREP qualitative requirement on data aggregation, an OSI and/or a deep dive or follow-up actions arising from a “BCBS 239 thematic review”.

At the same time, the COVID‑19 crisis raised specific concerns over the ability to produce and deliver reliable data in critical situations both to the management body and in response to supervisory requests (for example, some banks lacked information on COVID‑19 related deferrals that applied to the loan portfolios of some of their subsidiaries).

4.2.4 Supervisory expectations

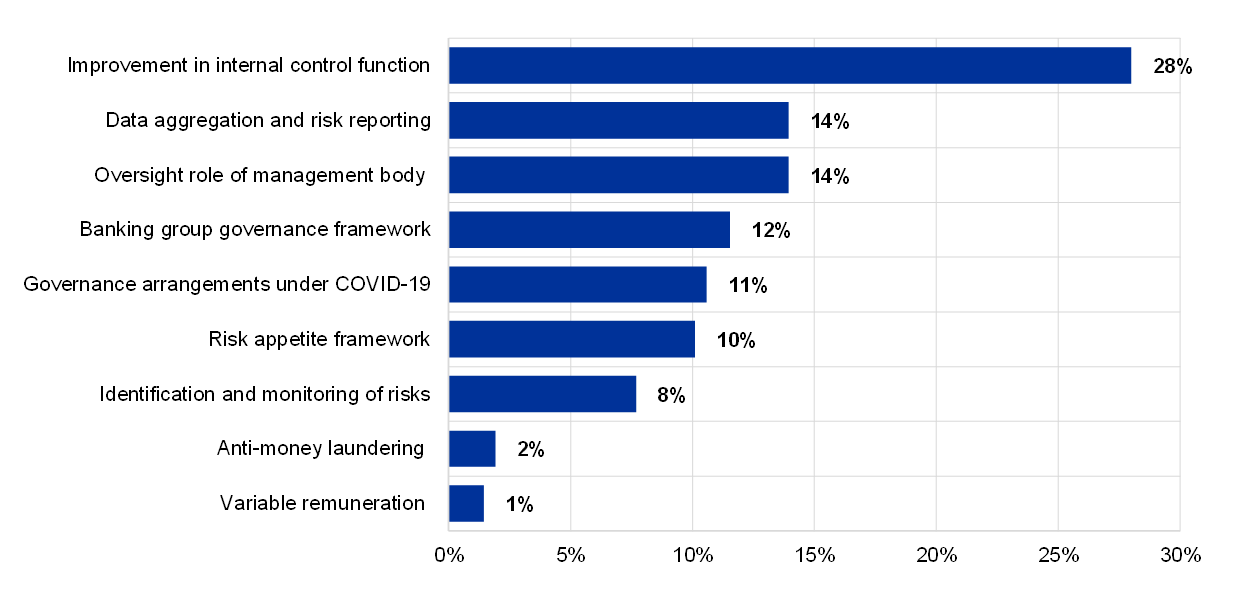

Most of the recommendations related to internal governance focused on improvements in internal control functions (28%), followed by data aggregation and risk reporting (14%) and the oversight role of the management body (14%). These three sub-categories represented more than half (56%) of the total number of qualitative recommendations issued for internal governance.

Chart 19

Breakdown of internal governance-related qualitative recommendations

Source: SREP 2020 values based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021.

Note: The chart overview does not include weaknesses which may have already been addressed by supervisory actions other than the qualitative measures and/or recommendations addressed to banks in the context of the SREP 2020.

Many of the internal control function recommendations focus on the formulation/communication of controls across group entities, for example, by enhancing oversight and steering capabilities across group entities and by reducing dependence on the group’s audit function. Several banks were also requested to reinforce/improve their compliance control functions.

Banks are expected to strengthen their reporting framework and capabilities to be able to respond to regulatory requests in a sustainable, timely and accurate manner.

JSTs will follow up on the implementation of those recommendations in the form of regular supervisory dialogue within the next SREP cycle. Heightened supervisory scrutiny is envisaged for the area of risk data aggregation and reporting and information management, which were identified as SSM supervisory priorities for 2021.

4.3 Element 3 – Block 1: Credit risk

4.3.1 Key messages

Deteriorating economic conditions during the pandemic slowed the pace of the ongoing reduction in non-performing loans (NPLs). There is, however, an embedded level of distress in loan books that is not yet fully evident.

The phasing out of fiscal support measures by the first half of 2021 may trigger cliff effects with respect to the quality of banks’ assets.

Supervisory focus is on ensuring that banks are adequately classifying and measuring risks in their balance sheets and that they are operationally prepared to address distressed debtors in a timely manner.

To encourage the appropriate outcomes in the context of the SREP, supervisors have communicated a significantly increased number of recommendations to banks which build on prior initiatives and are a significant facet of an integrated and dynamic credit risk strategy.

4.3.2 Focus on asset quality

In order to avoid an excessively procyclical response by the banking sector while ensuring a timely and appropriate identification and measurement of asset quality deterioration, several authorities and standard setters promptly provided guidance to banks regarding the implementation of the regulatory and accounting frameworks. Two of those initiatives were:

- EBA Guidelines on loan moratoria to avoid an overly mechanistic approach to loan classification;

- ECB guidance on IFRS 9 in the context of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

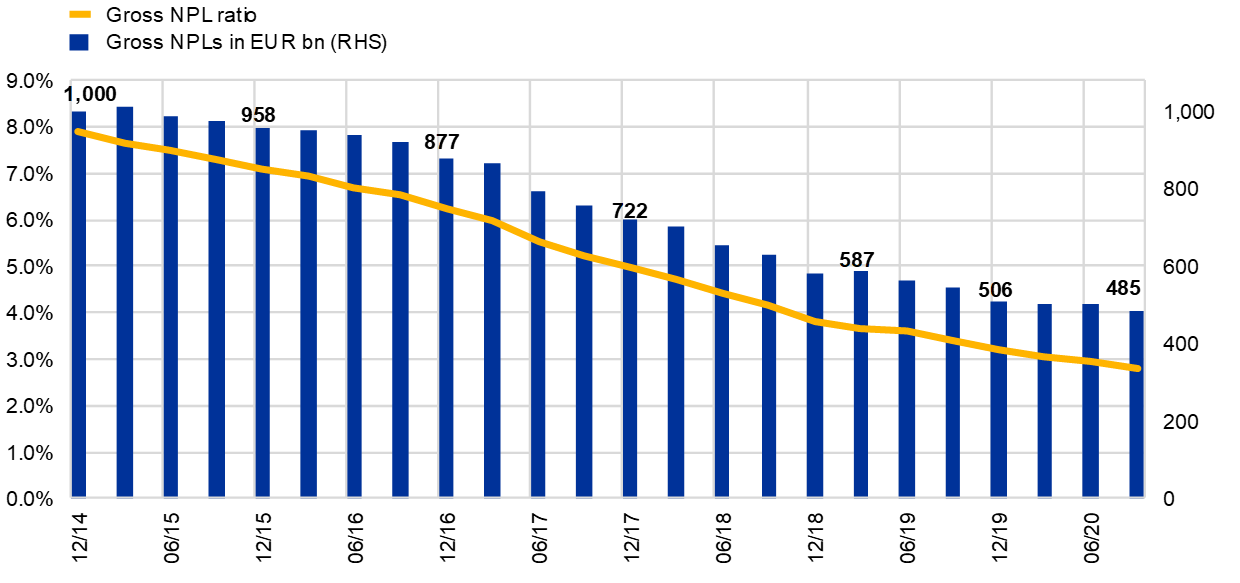

By the end of September 2020, the volume of NPLs held by SIs had been reduced to €485 billion, albeit with significant heterogeneity across banks. The additional challenges brought about by the pandemic have slowed down the steady pace of NPL reduction, which has been ongoing since the ECB assumed its supervisory responsibilities.

However, the majority of the expected COVID‑19 related credit risk distress has yet to emerge, as evidenced by a lack of significant increases in the NPL ratio arising from the start of the pandemic to date.

Chart 20

NPL developments for SIs

Source: Communication on supervisory coverage expectations for NPEs, August 2019 (updated with Q3 2020 supervisory data).

Delays/heterogeneous practices in the classification of exposures and unlikely-to-pay assessment were observed, resulting in an increased risk of the cliff effect. In order to minimise this, credit quality should be correctly reflected in banks’ balance sheets and distressed exposures should be both identified and addressed in a timely manner.

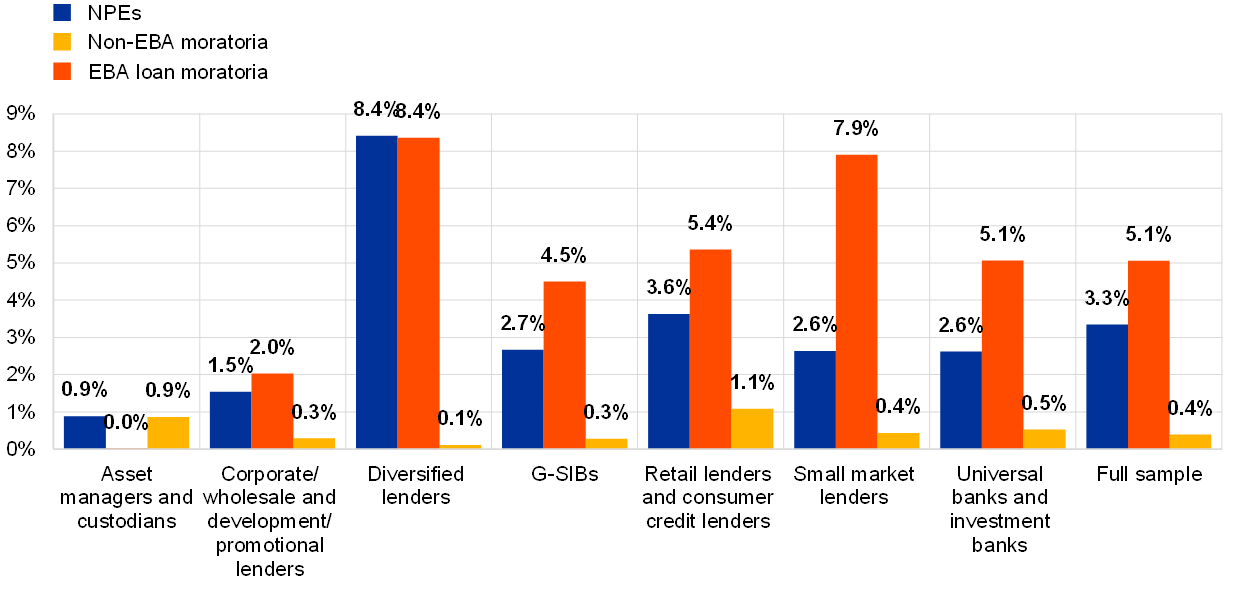

The following chart shows the year-end projections by banks of the proportion of assets classified as non-performing and performing exposures with forbearance measures, differentiating between: (i) exposures with EBA loan moratoria; (ii) exposures with other COVID‑19 forbearance measures.

Chart 21

Asset quality indicators

Sources: FINREP, banks’ own estimates of year-end projections as reported in the COVID‑19 reporting exercise as at Q2 2020.

The distribution amongst specific business models is reported in the following chart, which illustrates that the proportion of loans with non-EBA moratoria is rather low, representing less than 1% of total loans. These loans, which are subject to modifications that do not meet the criteria for EBA moratoria, should at least be earmarked for forbearance in order to put them under enhanced monitoring, facilitating the identification of longer-term deterioration at an early stage. Identification of forbearance is indeed one of the key concerns for supervisors, which have already asked banks to prepare their operational capacity to manage credit risk deterioration.

Diversified lenders reported the highest incidence of loans under EBA loan moratoria and NPEs.

Chart 22

Total loans under moratoria with breakdown by business model

Sources: FINREP, banks’ own estimates of year-end projections as reported in the COVID‑19 reporting exercise as at Q2 2020.

Note: The sample is made up of 98 SIs for which a SREP 2020 assessment was conducted and data are available.

4.3.3 Supervisory expectations

The ECB has communicated its expectations to all SIs on their operational preparedness and actions to minimise cliff effects and on the identification and measurement of credit risk in the context of the coronavirus (COVID‑19) pandemic. The JSTs are monitoring whether banks are following-up on these expectations on a case-by-case basis.

Supervisors issued a significant number of qualitative recommendations to address bank-specific concerns on credit risk to 80% of the banks.

The banks with the highest incidence of NPEs and loans under moratoria over total loans were all subject to dedicated recommendations. Findings related to the management of cliff effects and provisioning were more frequent for these banks compared with the wider sample of all SIs, although there were fewer recommendations on monitoring and reporting for these banks.

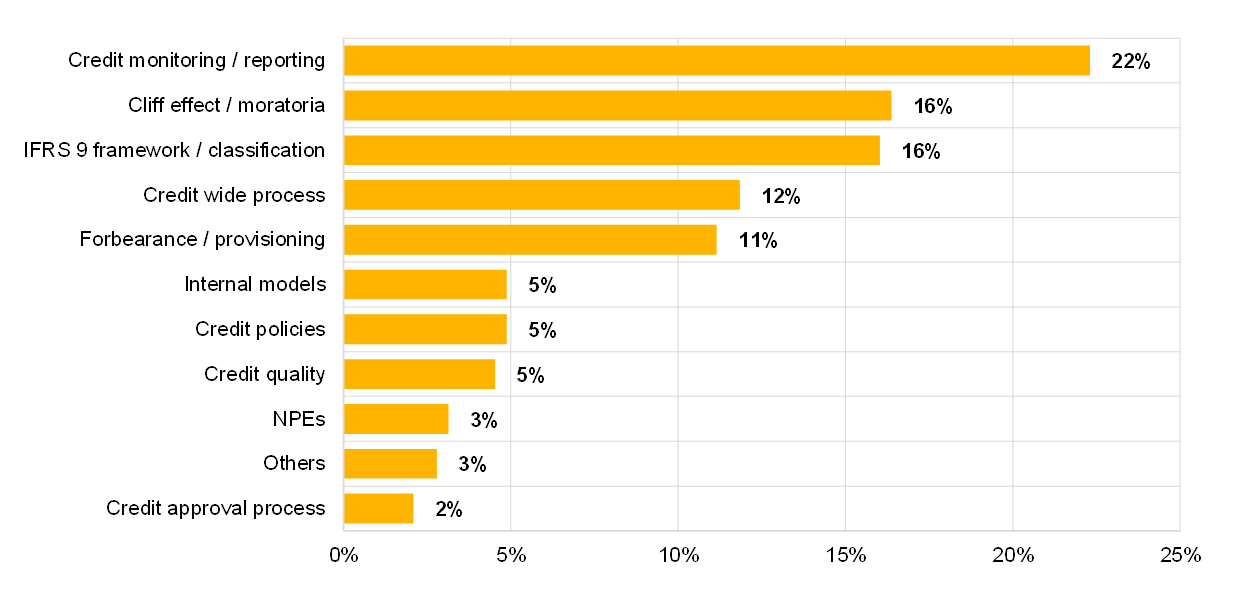

Three sub-categories represented over half (54%) of the total qualitative recommendations issued for credit risk. The sub-category most affected was that of credit monitoring/reporting (22%), followed by cliff effect/loan moratoria (16%) and the IFRS 9 framework/classification (16%).

Chart 23

Breakdown of credit risk-related qualitative recommendations

Source: SREP 2020 values based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021.

Note: The chart overview does not include weaknesses which may have already been addressed by supervisory actions other than the qualitative measures and/or recommendations addressed to banks in the context of the SREP 2020.

Recommendations relating to credit monitoring and reporting were a common source of concern across the JSTs, within the broader link between governance and credit risk, and reflected, in particular:

- data aggregation issues, frequently combined with weak capacity to monitor loan exposures limited SIs’ ability to take adequate measures (i.e. early recognition of signs of deterioration, IFRS 9 classifications and provisioning);

- system limitations which led to manual or absent flagging of EBA loan moratoria (particularly at the outbreak of the pandemic);

- JSTs’ concerns regarding robustness/transparency of management overlays.

JST recommendations on cliff effects arose from the maturity of various government interventions, as well as loan moratoria, together with the requirements for action already communicated to banks through other dedicated channels.

Concerns across JSTs were also related to the adequate identification of forbearance or the reinstatement of unlikely-to-pay assessments, mainly due to the treatment of loan moratoria.

4.4 Element 3 – Capital Adequacy and ICAAP

4.4.1 Key messages

In the 2020 cycle, the SREP requirements and guidance in total capital (excluding systemic buffers and the countercyclical capital buffer) remained at 2019 levels, thanks to ECB Banking Supervision’s frontloading of the P2R composition, creation of the possibility for banks to dip into P2G and adoption of the pragmatic SREP, for which P2R and P2G have been kept stable.

However, as credit risk impairments directly affected banks’ capital ratios, concerns about capital adequacy were particularly relevant for a few banks with limited CET1 capital headroom[10] over requirements.

Identified ICAAP weaknesses in capital planning and stress testing processes raised questions regarding the reliability of forward-looking capital projections, which could in turn restrict banks’ ability to successfully manage their capital position through the COVID‑19 crisis.

The ECB will further refine its methodology to assess banks’ capital plans in the forthcoming cycle. The results of those assessments – which will duly take into account the input from credit risk analyses – will inform the supervisory recommendations on banks’ distribution plans.

4.4.2 Focus on capital impact from regulatory relief measures

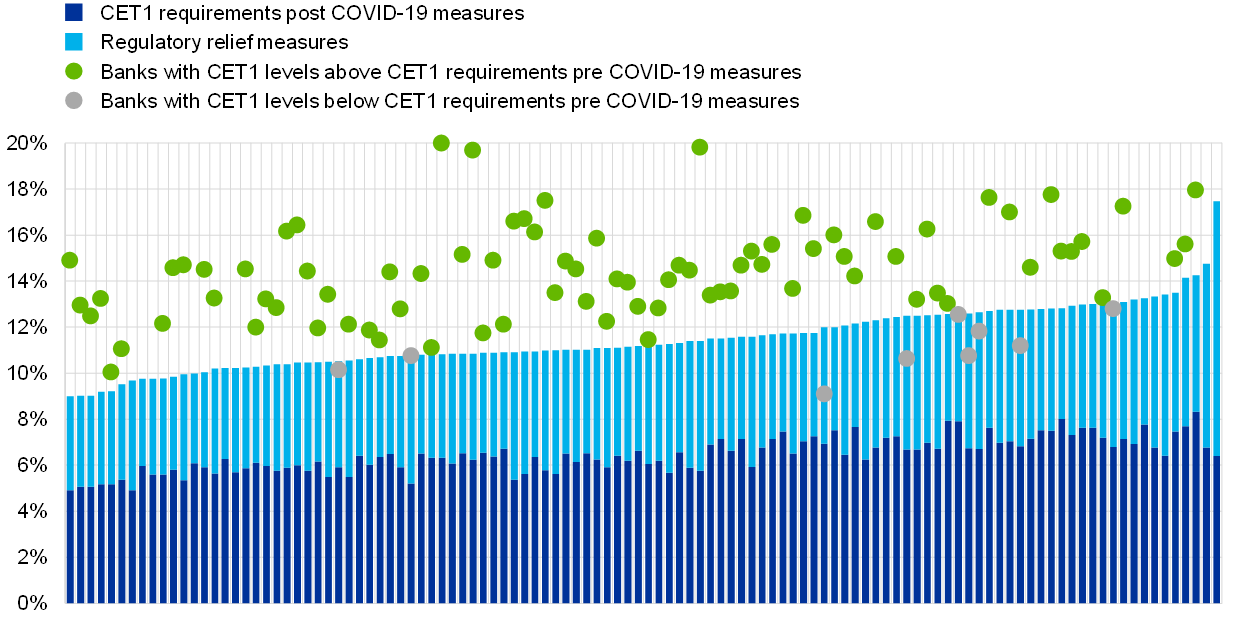

Despite concerns about capital adequacy in a few cases, euro area banks entered the COVID‑19 pandemic in a stronger capital position with respect to previous crisis episodes.

The frontloading of the new rules on the P2R capital composition decreased requirements for banks by around 90 basis points in terms of CET1.

However, the actual benefits in terms of CET1 relief amounted to around 30 basis points on average, after covering shortfalls in Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 additional Tier 1 and Tier 2 instruments with CET1 instruments.

As part of the ECB relief measures, banks can also fully use capital buffers including Pillar 2 Guidance, until at least the end of 2022.

Overall, nine banks are making use of the relief measures mentioned above, with CET1 levels based on Q3 2020 below the CET1 requirements and guidance pre-COVID‑19 measures.

Chart 24

Benefits in terms of CET1 from frontloading P2R capital composition and use of buffers* and P2G

Sources: SREP 2020 values (P2R and P2G) based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021. CET1 ratio as of Q3 2020, after covering post COVID‑19 shortfalls in Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 requirements with additional Tier 1 and Tier 2 instruments as of Q3 2020. Systemic buffers (G‑SII, O‑SII and systemic risk buffer) and countercyclical capital buffer as of Q3 2020.

Notes: * Regulatory relief measures are intended to mean: Pillar 2 guidance, capital conservation buffer, relief of systemic buffers (G‑SII, O‑SII and systemic risk buffer) and countercyclical capital buffer made available by national authorities, Pillar 2 composition in AT1 and T2, following the ECB decision on 12 March 2020 to frontload the Capital Requirements Directive V (CRD V), for which the P2R should have the same capital composition as that of Pillar 1. Therefore, P2R should be held with 56.25% in CET1 and 75% in Tier 1 as a minimum requirement.

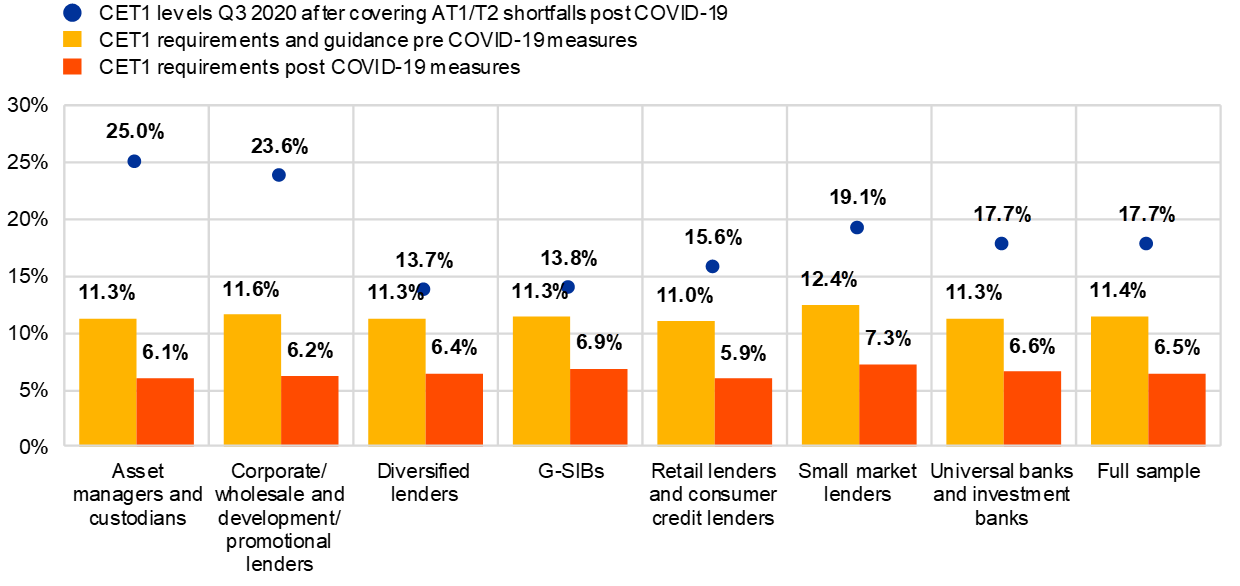

G‑SIBs and G‑SIBs universals had the lowest CET1 requirements and guidance.

Retail and consumer credit lenders had the highest relief in terms of CET1 and the highest CET1 headroom, while corporate and wholesale lenders had the smallest CET1 headroom, mainly due to their high exposure in sectors more vulnerable to COVID‑19.

Chart 25

Regulatory relief measures with breakdown by business mode

Sources: SREP 2020 values (P2R and P2G) based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021. CET1 ratio as of Q3 2020, after covering post COVID‑19 shortfalls in Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 requirements with additional Tier 1 and Tier 2 instruments as of Q3 2020. Systemic buffers (G‑SII, O‑SII and systemic risk buffer) and countercyclical capital buffer as of Q3 2020.

Notes: CET1 requirements and guidance pre-COVID‑19 includes the following regulatory relief measures: Pillar 2 requirement composition in AT1 and T2, following the ECB decision of 12 March 2020 to frontload the Capital Requirements Directive V (CRD V), Pillar 2 guidance, capital conservation buffer and the systemic buffers (G‑SII, O‑SII and systemic risk buffer) and countercyclical capital buffer as of Q4 2019.

4.4.3 Supervisory expectations

JSTs have expressed concerns about the reliability of banks’ capital planning frameworks (e.g. ability to produce reliable capital projections covering a three-year time horizon) as part of their ICAAP assessment amid a general deterioration in capital generation capacity due to reduced profitability.

Banks with low capital headroom[11] were subject to recommendations to enhance capital planning.

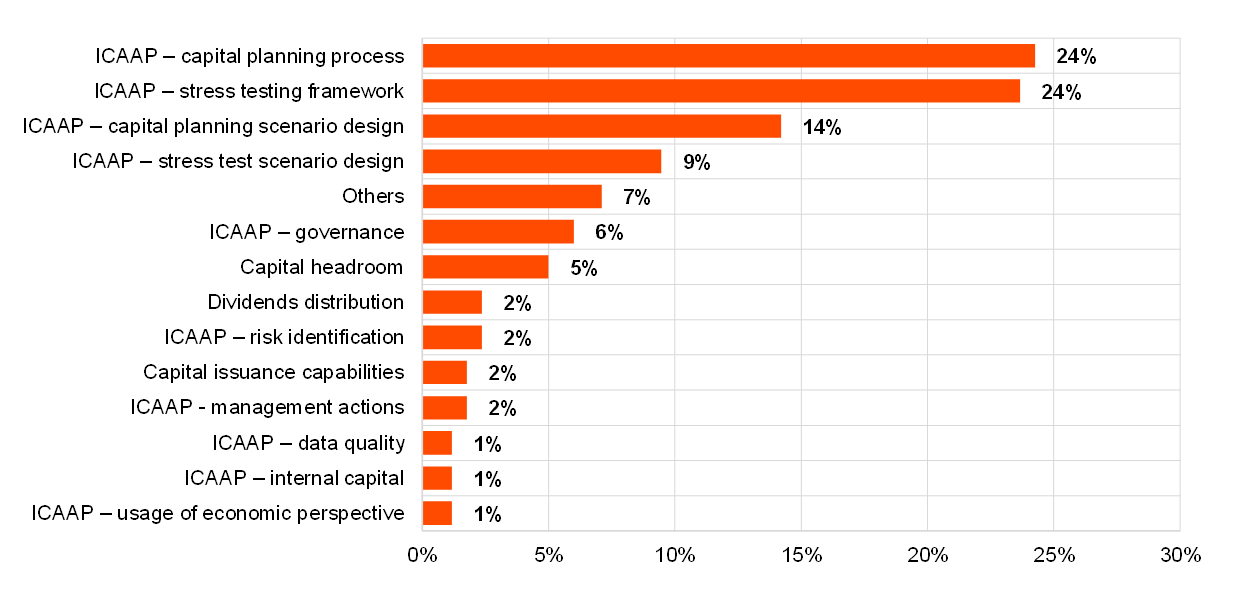

Recommendations relating to capital were stable with respect to the previous year. The sub-categories most affected were the ICAAP capital planning process (24%) and the ICAAP stress test framework (24%), followed by the ICAAP capital planning scenario design (14%). These three sub-categories represented more than 60% of the total qualitative recommendations issued for this category of risk.

Chart 26

Breakdown of capital/ICAAP-related qualitative recommendations (granular distribution)

Source: SREP 2020 values based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021.

Note: The chart overview does not include weaknesses which may have already been addressed by supervisory actions other than the qualitative measures and/or recommendations addressed to banks in the context of the SREP 2020.

As mentioned in the ECB report on banks’ ICAAP practices, banks are expected to continuously improve their internal processes. Indeed, sound ICAAPs are key success factors for effective risk management.

4.5 Other deep dives

4.5.1 Operational resilience

The SREP assessments of operational resilience in the face of COVID‑19 was broadly positive in terms of the overall fairly prompt and adequate response to the material impact of the pandemic.

Banks broadly kept their businesses running during the crisis, resulting in no significant rise in operational losses due to business disruptions or system failures.

Recommendations for improvement identified by JSTs included:

- updates/improvements in business continuity plans;

- reducing dependencies of critical banking services on third parties or foreign locations;

- remediation of IT and cybersecurity issues.

4.5.2 Anti-money laundering and financing of terrorism

While anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing supervision is not within the ECB’s supervisory mandate, the ECB plays an important role in identifying and reflecting the potential prudential consequences of money laundering and the financing of terrorism. As past cases have shown, money laundering and financing of terrorism concerns may have an impact on an institution’s safety and soundness, in some cases compromising its viability. At the same time, shortcomings in anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing controls may also raise red flags relating to broader prudential concerns that are in the ECB’s purview, such as a bank’s governance and risk management framework or the sustainability of its business model.

The pragmatic approach to the SREP 2020 allowed ECB Banking Supervision to factor prudential concerns relating to money laundering and the financing of terrorism into the SREP 2020 assessments.

Prudential concerns relating to money laundering and the financing of terrorism were reflected in different parts of the SREP 2020 assessments. They were concentrated on issues related to internal governance arrangements and operational risk management. For instance, in the area of internal governance and risk management, prudential causes of money laundering and financing of terrorism concerns might be rooted in weak internal control frameworks (i.e. deficiencies in the compliance function) or insufficient oversight of money laundering and financing of terrorism risks by the management body.

5 Less significant institutions

5.1 Key messages

The common SSM SREP methodology for the less significant institutions (LSIs), gradually being used since 2018, continues to be rolled out by the national competent authorities (NCAs), with a view to covering all LSIs by the end of 2021.

In 2020, the majority of LSIs were assessed by the NCAs either using the common SSM SREP methodology for LSIs or the pragmatic SREP approach agreed with the NCAs in March 2020 (derived from the SIs’ pragmatic approach and in line with the EBA Guidelines[12]).

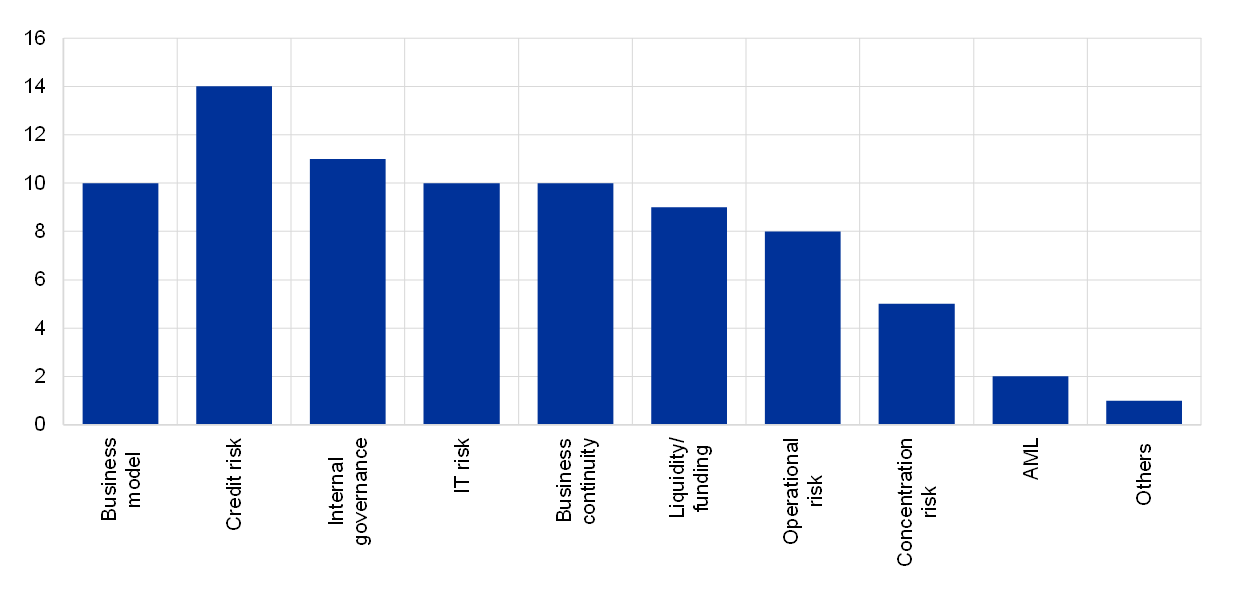

NCAs reported that the most relevant areas for them in the SREP 2020 assessment were credit risk, governance, business model, IT risk and business continuity. Under the pragmatic approach, the intensity of assessments and/or area of focus may have varied.

Chart 27

Most relevant areas of SREP 2020 assessment identified by NCAs

Source: Structured feedback template collected in August 2020.

The majority of NCAs kept Pillar 2 requirements unchanged in 2020, but the implementation of P2R and P2G was still heterogeneous across NCAs.

Consolidation efforts continue, albeit at a slowing pace. The overall decrease in the total number of SSM banks (significant and less significant banks) is primarily a reflection of the fact that there are fewer LSIs as a result of the high number of structural transformation plans in the cooperative sector and large waves of consolidation witnessed in recent years.

6 Conclusion

The supervisory priorities for 2021 as defined by ECB Banking Supervision build upon the assessment of the key risks and vulnerabilities in the banking sector. In 2021, four key areas – materially affected by the current COVID‑19 crisis – will be subject to a particular focus:

- ECB Banking Supervision will prioritise its assessment of the adequacy of banks’ credit risk management, operations, monitoring and reporting practices. Particular emphasis will be put on banks’ ability to identify asset quality deteriorations at an early stage, book accordingly adequate and timely provisions but also take the necessary actions towards arrears and NPL management.

- Moreover, it is essential that banks have in place sound capital planning practices, based on capital projections which adapt to a dynamically changing environment, particularly in a crisis situation such as the current pandemic. In addition, the EU-wide stress test coordinated by the European Banking Authority will be conducted in 2021 and will be an important element in gauging banks’ capital strength.

- Banks’ profitability and business model sustainability remain under pressure from the economic environment, low interest rates, excess capacity, low cost efficiency, and competition from banks and non-banks. The COVID‑19 pandemic in part amplifies this situation. ECB Banking Supervision will continue to challenge banks’ strategic plans and underlying measures taken by banks’ senior management to overcome existing deficiencies.

- The supervisory focus will remain on governance, with a particular emphasis on risk data aggregation capabilities and information systems, as well as on the adequacy of banks’ crisis risk management practices. ECB Banking Supervision will continue its assessment of banks’ internal controls, also with a view to mitigating money laundering and terrorism financing risks.

Further structural activities going beyond the impacts of the COVID‑19 pandemic will be carried out in 2021, especially related to banks’ alignment with the expectations stipulated in the ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risks and their preparations for implementing the new rules resulting from the finalisation of Basel III. Depending on how the crisis develops, ECB Banking Supervision may further reprioritise its activities.

Read the press release© European Central Bank, 2021

Postal address 60640 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Telephone +49 69 1344 0

Website www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu

All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

For specific terminology please refer to the SSM glossary (available in English only).

- Eurostat euroindicators, 8 September 2020.

- Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, December 2020.

- See EBA/GL/2020/10 Guidelines on the pragmatic 2020 supervisory review and evaluation process in light of the COVID‐19 crisis, EBA, July 2020.

- Under Capital Requirements Directive V (CRD V), which came into effect on 1 January 2021, the P2R should have the same capital composition as that of Pillar 1. Therefore, P2R should be held with 56.25% in CET1 and 75% in Tier 1 as a minimum requirement.

- Mismatches are due to the approximation to 1 decimal.

- Under Capital Requirements Directive V (CRD V), which came into effect on 1 January 2021, the P2R should have the same capital composition as that of Pillar 1. Therefore, P2R should be held with 56.25% in CET1 and 75% in Tier 1 as a minimum requirement.

- In the context of the COVID‑19 pandemic, on 27 March 2020 the ECB Supervisory Board decided to take a pragmatic approach to the SREP 2020. As a result, and with a view to providing capital relief and supporting banks, the qualitative measures were formally replaced by qualitative recommendations in order to address supervisory concerns, unless justified by exceptional circumstances affecting an individual institution. Therefore, measures and recommendations should hereinafter be defined as recommendations in this specific context.

- Qualitative measures were issued for 91 banks in the SREP 2019 cycle. In addition to requesting SREP qualitative measures, the JSTs may have issued qualitative recommendations (not legally binding) via SREP decisions or have requested other measures outside of that scope, stemming from OSIs, deep dives or day-to-day tasks carried out as part of their supervisory activity.

- For additional information see the article entitled “Good governance in times of crisis” in the ECB’s Supervision Newsletter.

- Capital headroom is considered as the difference between a bank’s capital requirements and its capital ratio.

- Capital headroom is considered as the difference between a bank’s capital requirements and its capital ratio.

- See EBA/GL/2020/10 Guidelines on the pragmatic 2020 supervisory review and evaluation process in light of the COVID‐19 crisis, EBA, July 2020.