- SUPERVISION NEWSLETTER

Extinguishing sparks before the fire: credit crisis managed well

13 August 2025

Authors: Marie-Therese McDonald, Claudio Castro Quintas, Frenk Chen, Mário Roldão, Sara Rizza and Tim Fröhlke

In recent years, borrowers have faced various crises, such as the pandemic, military conflicts and technological and regulatory changes. Such crises can generate oil and energy price volatility, as well as negative effects on supply chains, imports and exports. More recently, the uncertainty around tariffs is potentially affecting the volume of trade. In addition, the automotive sector is facing headwinds arising from shifts in technology and demand dynamics. Faced with this volatility, it is critically important that banks are able to identify and manage risks properly, and they must remain prepared to safely navigate any potential crises that might arise.

Against this backdrop, the ECB has carried out a targeted review of lending to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) across a sample of banks. The SME portfolio was selected based on several factors: (i) it is a material portfolio for many banks; (ii) SMEs are often affected early during economic downturns; and (iii) managing SME portfolios typically requires considerable resources because of their high number of borrowers, which increases the importance of efficient and effective processes for banks. The ECB’s review focused on a sample of significant banks from across Europe and some less-significant banks from Germany (given their materiality in the German banking sector, especially for SME financing).

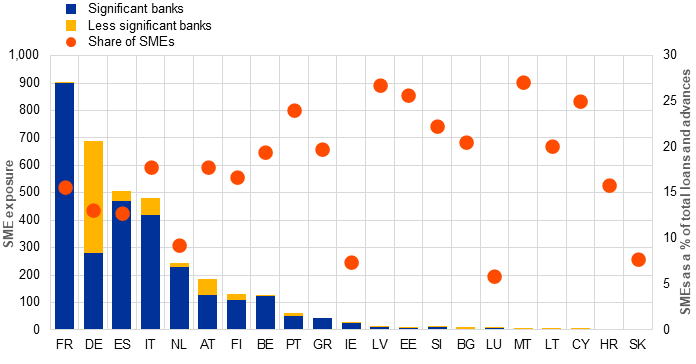

SMEs are important for the economy of the European Union. According to data from Eurostat, in 2024 SMEs accounted for 65.1% of employment and for 53.6% of the total added value generated in the non-financial business sector[1]. While SMEs also receive loans and funding from non-bank entities, banks still account for a very large proportion of SME funding as highlighted in Chart 1.

Chart 1

The breakdown of SME exposure for significant banks and less-significant banks and the share of SME exposure from total loans and advances, by country of lender or banking group

(left-hand scale: billion euro; right-hand scale: percentage of SMEs from the total loans and advances)

Source: FINREP data.

Note: The data shown in this chart is for the fourth quarter of 2024.

The review looked at how prepared banks would be to face a potential crisis. A crisis can spread across the economy, be confined to a single sector or firm, or spill over to connected sectors. The concentration of sectoral risks therefore becomes an important element to consider.

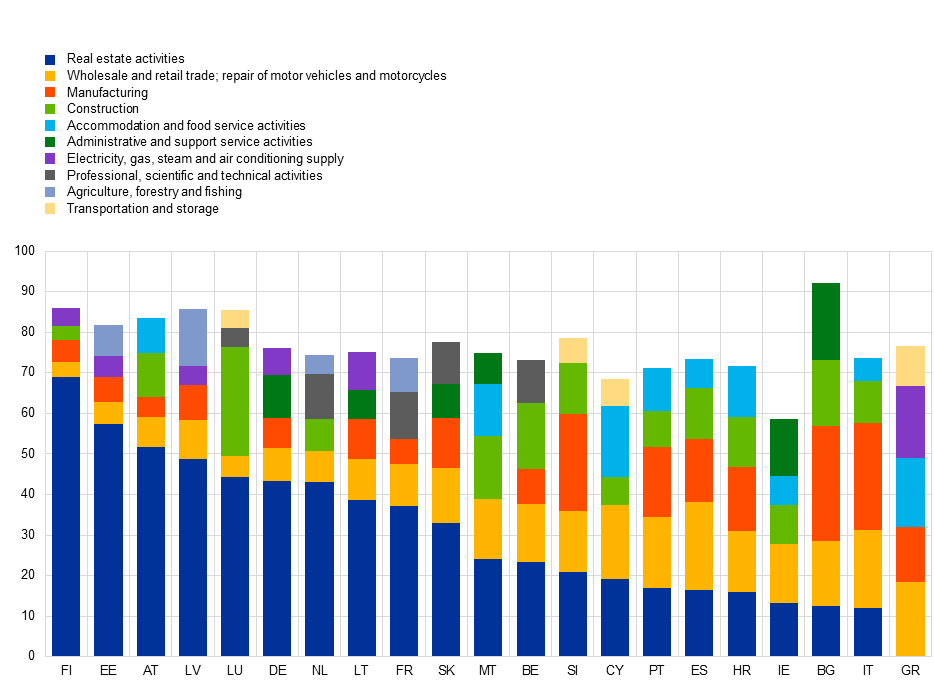

Chart 2

Breakdown of the top five sectors by country for SME borrowers

(percentage of the total loans and advances)

Source: AnaCredit.

Note: This chart shows data for the fourth quarter of 2024 for both significant and less-significant banks.

Banks’ lending portfolios show a high degree of sectoral concentration (Chart 2). This concentration will be monitored by the ECB in the event of an emerging sectoral or large firm crisis. Unlike other sectors, exposures to the real estate sector are material for almost all countries. Real estate has faced challenges in recent years for a variety of reasons, with the office sector being the most negatively affected. However, the issues have largely been contained to Germany, Austria and Luxembourg.

With regard to the credit quality of the SME portfolio, the non-performing loan (NPL) ratio remained stable at 4.78% as of the end of the first quarter of 2025, staying above the NPL ratio of the total non-financial corporate portfolio, which was 3.47%. The total coverage ratio for the SME portfolio is the same period was 3.02%.

How banks manage emerging crises in the SME portfolio

The targeted review included 14 entities of significant banks, corresponding to nine banking groups, as well as four less-significant banks, including German savings and cooperative banks. It was carried out off-site based on documentation provided by the banks and it also included a half-day workshop with each bank

The review examined how banks address potentially distressed borrowers at the onset of a crisis, concentrating on several critical risk management areas: governance, rating assignment procedures, early warning systems and the evaluation of borrowers’ financial difficulties. The key findings and conclusions are outlined below.

Some banks are better prepared for a potential crisis than others

Banks differ significantly in how prepared they are to deal with potential emerging crises. Banks should not only be geared towards granting loans and selling products to customers; they should have the infrastructure, policies, procedures and resources to enable them to adjust as smoothly as possible to an environment where borrowers become distressed. To a large extent, this is connected to their level of automation and the robustness of their digital infrastructure, including data collection capabilities.

- The best-performing banks had a solid IT infrastructure, and some had even built advanced tools using artificial intelligence. They have workflows and procedures which allow them to efficiently and effectively deal with crises situations. These processes are generally well designed, embedded within their IT systems and automated to the greatest extent possible. Risk management processes are also well understood and implemented by staff.

- At the other end of the spectrum, some banks had more outdated approaches to risk management. These banks rely on manual processes and tools, such as basic templates, with an over-reliance on expert judgement. Their procedures are unclear and sometimes convoluted, leading to delays in risk management even in a business-as-usual environment, as relationship managers are left to decide how and when to deal with risks that need to be manually identified. Very often those weaknesses are strongly correlated with a weak IT infrastructure, which means that these entities would likely face serious difficulties in the event of a crisis.

- Most banks, however, landed somewhere in the middle: they lack the advanced IT tools seen in entities at the forefront, but they do have clear procedures and tools to support their processes, even if manual. These banks would likely be able to handle a moderate crisis but may struggle if a crisis were to become more protracted.

Weak risk management goes hand in hand with inadequate data and IT infrastructure

Banks should utilise all available data from internal and external sources, for example behavioural information from current accounts, credit card accounts, credit bureau information and financial information collected from borrowers. These data are not only the basis for computing ratings, but are also needed for early warning systems and IFRS9 models. Ultimately, these data form the foundation of effective risk management, as well as the calculation of capital and provisions. It is therefore crucial that banks establish processes to ensure all relevant data are available and up to date. Where information becomes outdated, especially in the case of ratings, further steps should be taken to ensure the timely retrieval of relevant data updates or the application of conservative treatment. However, some banks are not able to retrieve relevant information in a timely manner and some do not take measures to ensure that there is a conservative treatment when ratings become outdated. This has direct implications for capital computation and credit risk management, as those banks may not be aware that a borrower’s financial situation has changed since the most recent information updates.

For banks using the internal ratings-based approach, ratings are used as an input variable to calculate the capital required to cover unexpected losses. The “use test” requirement dictates that these ratings should also be used in a bank’s risk management processes and should play a central role in identifying risk across the credit cycle. For these reasons, ratings are one of the main pillars of credit risk management but, on their own, they are not entirely sufficient. Other systems also play an important role and provide other measurements of risk: early warning systems help identify early signs of distress, while IFRS9 models cover for expected losses and identify changes in risk levels since loan origination.

While it is important that ratings feed into these other systems, they cannot, by design, be the main and only input. Banks should have clear feedback loops in place across each element of the risk cycle to ensure information is captured in the right way. However, banks with weaker data and IT infrastructure tend to overly rely on ratings in their early warning systems and credit risk processes. They lack a considerable amount of relevant data given their failure to invest sufficiently in IT and data infrastructure.

Without effective early warning systems, banks need to rely on slower manual processes

Early warning systems play a pivotal role in a bank’s ability to identify and respond to emerging credit risks or to a crisis, especially in the case of SMEs that have a large number of borrowers. Focusing on the early detection of risk enables banks to identify potentially distressed borrowers and to intervene early, helping them avoid a build-up of non-performing loans and preventing more significant losses down the line. In times of stress, early detection also supports borrowers and therefore, ultimately, the wider economy.

Experience shows that failing to recognise early warning signs and declining asset quality leads to understated loan loss provisions. Banks that rely heavily on manual processes tend to be delayed in identifying risks, to have unstructured follow-up processes to engage with their borrowers, and to be more prone to responding too late when potential problems arise. This is particularly important in the context of SMEs, as banks might lack the resources to deal with a deterioration of clients’ creditworthiness across the board. For example, the review revealed that many banks have not implemented early warning indicators for specific sectors despite having a material exposure to a sector, while some banks rely on late indicators such as insolvency or bankruptcy and days past due, which are not good at identifying early distress. This is mainly because of the lack of other data sources. In other cases, while it is positive that the indicators were used, the thresholds for important risk measures, like interest coverage ratio (ICR) or leverage ratio, were set to levels more appropriate for spotting defaults, not to catch early warning signs. For example, the ICR had to fall below one or the leverage ratio had to go above ten before triggering an alert.

Sectoral risks need to be managed better

Even in a general economic crisis, risks affect different sectors in different ways. For example, the pandemic had a wide-reaching negative impact across much of the economy, but the hospitality sector rebounded dramatically whereas the real estate market struggled, especially the office segment.

In recent years, banks have increasingly managed the risks in their portfolios through sectoral risk management. As resources are finite, this segmentation is an effective way to allocate resources. While this is a positive step, banks have not yet mastered this practice. Only a small number of banks regularly assess sectoral risks and assign different outlooks to different sectors. These outlooks are considered within the credit-granting process and for the regular borrower assessment. Moreover, they feed into the banks’ early warning systems to identify higher-risk borrowers. It is also an efficient way to manage risk, as it operates within an established IT system. However, most banks either do not assess sectoral risks at all, or they only do it only superficially or on an ad hoc basis following sectoral crises, e.g. during the energy crisis in 2022.

The approach to risk management is similar for large and small banks

The review found minimal practical differences in how banks of various sizes manage SME credit risk, including between significant and less-significant institutions. This was consistent across all reviewed aspects of credit risk management and regardless of the supervisors’ need to ensure proportionality.

Although less-significant banks are typically a lot smaller than significant banks, in terms of total assets, the savings and cooperative banking groups provide central IT infrastructure and common methods, systems and processes for their associated banks, and the less-significant institutions that were in the review were part of these groups. This ensures a level of professionalism that individual, smaller banks typically could not maintain on their own. This review focused in particular on shared IT systems in the context of early warning systems and rating systems.

Good practices for managing emerging risks

Proactivity is crucial for effectively managing an emerging crisis. This includes (i) proactive identification of risks through proper early warning systems and sectoral risk analysis, (ii) proactive engagement with potentially distressed borrowers and (iii) proactive offering of sustainable solutions for borrowers that are still viable.

Example of clear and effective framework for early risk management

Robust data and IT infrastructure and sound governance

Sound data and IT infrastructure are essential for effective risk management. Leading banks use automated systems, allowing risk analysts to focus on borrower engagement and assessments instead of manual tasks. Smaller banks can also benefit from investing in data and IT infrastructure, thereby reducing long-term costs.

While poor IT infrastructure is largely a result of insufficient investment, lacking data is not always entirely bank driven. In some countries, national credit register data are not easily accessible by banks. Entrenched practices may also block banks from gaining critical information, for example where smaller SME borrowers historically have not provided financial information on a regular basis. However, a bank can always require financial information from its borrowers through their loan agreements and facilitate the collection through easy-to-use tools and incentives.

Another important aspect of effective risk management relates to governance. As mentioned above, resources are finite. Segmenting portfolios using factors like the borrower’s turnover, total lending and sector, as well as the complexity of the exposure, are useful ways to define the level of resources needed to manage the customer relationship. Furthermore, the allocation of tasks between the different lines of defence should be fully clear to ensure an efficient response to early signs of distress in a portfolio, especially if escalation is required. The less clear the governance arrangements are, the more time it takes to manage the risk.

When it comes to sectoral risk, some banks classify economic sectors and subsectors into different risk categories based on, for example, whether these bear high, medium or low risk, and reassess the categorisation on a regular basis. All exposures that are flagged as “high-risk” have a more conservative treatment in terms of early warning signals and/or additional monitoring. This categorisation can then also be applied to other aspects of risk steering, such as pre-screening credit-granting limits or reducing risk tolerance limits for the sector.

For smaller SME borrowers, banks make an increased use of automated decision tools at loan origination. It is positive to see that some banks have complemented and reinforced these tools with a shadow back-testing assessment, which is conducted by credit risk managers on a monthly basis. In practice, a random sample of 10-20% of automated approved deals are analysed by the risk experts to cross-check whether they would have reached the same conclusions.

Banks generally update their ratings, at least on a yearly basis. However, it is not always possible to collect the necessary financial information and re-rate all borrowers within this one-year cycle. When this happens, as required by regulation, several banks take practical steps to ensure that ratings are adequately conservative. For example, in line with the ECB Guide to internal models, ratings are continually downgraded as the information becomes more outdated, and for unrated clients the rating is set equal to the worst rating grade. Concerning the borrowers carrying higher risk and therefore needing more frequent rating review, some banks create a direct link between a high-risk borrower and the watchlist categorisation. This is considered to be good practice as it connects the different elements of the credit risk management cycle.

Since no two crises are the same and no model will ever be able to perfectly capture every risk, ratings can be overridden if key information has not been captured. Banks should therefore have a process to embed information that might not be properly captured in the rating. To be prepared for a crisis, it is a good practice if banks already have a list of pre-defined override options which sets out in detail the situations and information that can change the rating and the related effects on the rating. Moreover, overrides improving the rating should be conservatively limited to a reasonable extent.

Robust early warning systems

The next key element of managing a crisis is having a robust early warning system. A suitable system is based on a diversified pool of information sources, relies on automation to the highest extent possible and complements the bank’s rating systems. Automated sourcing of early warning indicators, particularly those based on customer behaviour (e.g. payment patterns) and external data (e.g. credit bureau information), allows institutions to respond proactively and to prioritise high-risk clients. Banks displaying good practices have sufficiently integrated their financial warning indicators and clearly defined thresholds that align with processes spanning the entire credit risk cycle. When trigger levels are reached or more critical warning indicators are breached, these should automatically suggest higher-priority classifications. For example, banks generally use cashflow metrics such as the loan-to-value ratio, ICR and debt service coverage ratio at origination to determine if a loan should be granted. These metrics should also appear in the early warning system alongside other elements of the risk management cycle as they determine repayment capacity. However, the threshold levels should be calibrated to their purpose, in this case the early identification of risk.

A strongly data-driven early warning system entails thorough data quality assessments and back-testing to ensure that predictive power remains sound and robust over time. Validation should cover both qualitative aspects (conceptual soundness, design logic, analysis of manual transfers on watchlist) and quantitative performance (predictive accuracy, false positive rates, emerging time frame, recurrence rate) to understand whether the warning system is accurately predicting jumps to default and whether the alerts lead to the intended risk management actions.

An effective early warning system is only as good as the action banks take when a borrower is identified as potentially distressed. Timely and consistent follow-up can be made easier through tailored workflows that depend on the size and complexity of borrowers, through clearly defined escalation paths and through a structured customer outreach. Best-in-class banks use standardised warning letters and automated communication, tailored according to the days-past-due status and the type of alert triggered by the early warning system. This is particularly useful for smaller-sized borrowers. These actions are supported by checklists and standardised templates for information collection.

As already mentioned above, risk detection capabilities are significantly improved when sectoral risks are well embedded into the early warning system. Sector-specific information helps to identify forward-looking vulnerabilities that may not be evident at the individual borrower level, and which may affect large cohorts of borrowers. It should cascade down to inform borrower-level monitoring while integrating with macroeconomic indicators. For example, deteriorating conditions in a specific sector can directly increase the severity level of individual signals of credit deterioration for borrowers in that sector. This sectoral integration is particularly important for SMEs, where performance is closely tied to sectoral dynamics, and financials may provide a delayed picture in comparison to the actual riskiness of a given customer.

Once a bank has identified a potentially distressed borrower and proactively reached out to discuss their financial situation, the bank should have the necessary tools to carry out the financial analysis of the borrower. Best practices here include cashflow projection tools which assist analysts in calculating risk metrics and have built-in hurdle rates. To bring in the sectoral element once more, some banks had different hurdle rates depending on the sector, for example different maximum leverage for agriculture, manufacturing, etc.

Lastly, when the financial analysis of the borrower has been completed, it is important to categorise the risk. In the example above, borrowers are either returned to the performing category, placed in various watchlist categories corresponding to different intensities of monitoring, or flagged as unlikely to pay. For this to work, there should be a framework which makes it easy to determine the appropriate category for each borrower following the assessment.

Supporting strong risk management

All of the above good practices are aimed at facilitating more efficient and effective risk management. When implemented correctly, such risk management means that banks can allocate resources and prioritise higher risk clients in the best way possible, and it should in fact cost less in the long run. Furthermore, having established tools and processes which are as automated as possible does not mean that expert judgement is eliminated. In fact, it means that experts have the time to engage with borrowers and assess the risks. Clarity in the framework means that a consistent outcome is more likely across the portfolio which is aligned to the banks risk strategy. When facing a crisis, this can only be seen as the best outcome.

The authors would like to thank the following contributors: Joel Urho Vääräniemi, Tobias Beck (ECB Banking Supervision); Christian Schröer, Murat Köster, Anna Gockel (Deutsche Bundesbank), Thomas Ottersbach (German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority).

See Schulze Brock, P., Katsinis, A., Lagüera González, J., Di Bella, L., Odenthal, L., Hell, M., Lozar, B. and Secades Casino, B., Annual Report on European SMEs 2024/2025, SME performance review, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2025.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts