13 November 2024

Authors: Sharon Finn and Naomi Rolano

At a recent ECB conference[1] selected banks and ECB supervisors talked about the challenges faced during the collection of energy performance data and how to solve them. Participants also discussed physical risk matters for the real estate sector. This article summarises the experiences and good practices that the banks were willing to share. The banks in attendance were chosen based on the progress they had made, which was assessed using objective criteria and quantitative data from a range of supervisory initiatives. They came from a range of euro area countries, ensuring representativeness and providing an opportunity to discuss differences in national regulation.[2] The main learnings from the conference were as follows.

- The selected banks had made significant progress in collecting energy performance data at loan origination. It may be feasible to find a common solution for all banks.

- Although challenging, progress should also be possible for the existing stock of real estate on banks’ balance sheets, although there is no one single solution. Instead, a comprehensive strategy using a combination of different approaches will increase success levels and close data gaps.

- It is easier to find a solution for commercial real estate (CRE) than for residential real estate (RRE) given the strong client relationships and regular valuations associated with the former. However, this has not yet translated into improved coverage of energy performance data for the real estate stock already sitting on banks’ balance sheets.

- An increasing number of hazard events is forcing banks to seek more mitigants to cover damage. Banks rely extensively on external data providers when collecting data for physical risk.

What are energy performance data and why are they necessary?

The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive sets minimum energy performance standards for residential and commercial buildings. To achieve a zero-emission building stock by 2050, the transition for the real estate sector will entail:

- reducing the average primary energy use of residential building stock by 16% by 2030 and by 20-22% by 2035. Some 55% of the decrease in average primary energy use will have to be achieved by renovating the worst-performing residential buildings.

- renovating the 16% worst-performing buildings by 2030 and the 26% worst-performing buildings by 2033.

The Directive will be transposed into national regulation by May 2026, with the aim of increasing the renovation rate for European buildings. However, to establish which buildings need to be renovated and predict which customers will ask for a bank loan, banks need data on the energy efficiency of buildings.

Banks also need to ascertain the energy performance of buildings from a credit risk management perspective. Banks hold real estate as collateral for loans on their balance sheets and need to estimate the recoverable value of this collateral in the event of default. The value of real estate is increasingly being influenced by climate-related factors. Banks that do not fully understand this risk are potentially leaving themselves exposed to lower recovery values in the event of borrower distress. They would need to increase provisions in the long run, which would affect profitability. As banks need to be able to adequately measure and manage the credit risk associated with collateral, access to reliable energy performance data on real estate is fast becoming a fundamental part of credit risk.

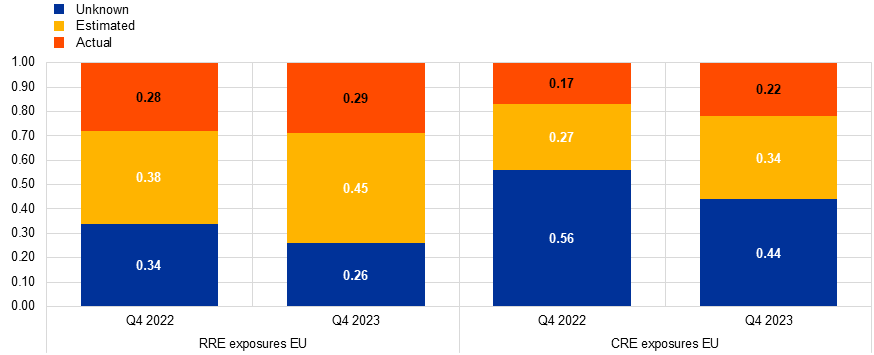

Looking at the quantitative data obtained from various supervisory exercises, fewer than ten banks under European banking supervision possess more than 50% of the actual (as opposed to estimated) data on energy performance certificates (EPC) for both the RRE and the CRE sectors. Looking at the data aggregated at the European level (as per banks’ disclosures in their Pillar 3 reporting), there is still a long way to go to reach a satisfactory amount of actual data.

In the absence of actual data, banks make use of estimations. These were extensively assessed by the ECB in the context of the 2022 climate risk stress test exercise and good practices have already been shared with the industry.[3] However, even if proxies are taken into consideration, the share of unknown data is, on average, quite high.

Chart 1

Distribution of EPC labels for the collateral of banks under European banking supervision

(percentages)

Source: short term exercise data collection as of December 2023, aggregated data at the EU level from banks under European banking supervision and subject to the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process.

A common and reasonable approach for new flows

With regard to new flows, banks and supervisors are of the same view: energy performance data should be collected at loan origination and stored appropriately in IT systems.

The conference participants’ conclusions were as follows.

- Aim for excellence not perfection. Achieving 100% coverage at loan origination is not always feasible given the existence of exceptions (such as buildings on historical sites or smaller than 50m2 that are not subject to an EPC). However, as the banks explained, they are aiming to achieve significant coverage targets (up to 95%) in a short period of time (one to three years). These banks will soon have substantial data availability due to loan book rollovers.

- Nothing happens by chance. Invited banks had active management boards and committees that had been pushing for EPC data to be gathered at loan origination. The earlier a bank starts to collect data, the better the outcome in the long term. Indeed, any action plan or initiative aimed at reaching higher coverage must be endorsed by the board.

- Allocate people. Dedicated budget must be in place so internal staff can be allocated to EPC validation checks and second-level controls. As an example, a “traffic light” alert in a bank’s IT system to signal data coverage for new business is a good approach. When this alert turns red, this means that the data coverage of the local entity is not sufficient and a message is sent to the holding company so that data quality checks can be performed. Another way to monitor the progress is setting up a new dashboard for EPC data validation control, to be used by the bank’s operations centre for rectification activities.

- Invest, invest, invest. The invited banks explained that it is essential to invest in and develop IT systems with sufficient granularity. Information that sits idle in paper files instead of the banks’ IT systems is unusable and wasted.

Focus area 1: a deeper look at an example of good practice for collecting EPCs at origination

Banks explained that they had started to collect EPCs manually from customers, in some cases before 2010. They then invested money in digitalising the process to ensure that data are available and are used for risk management and data reporting purposes.

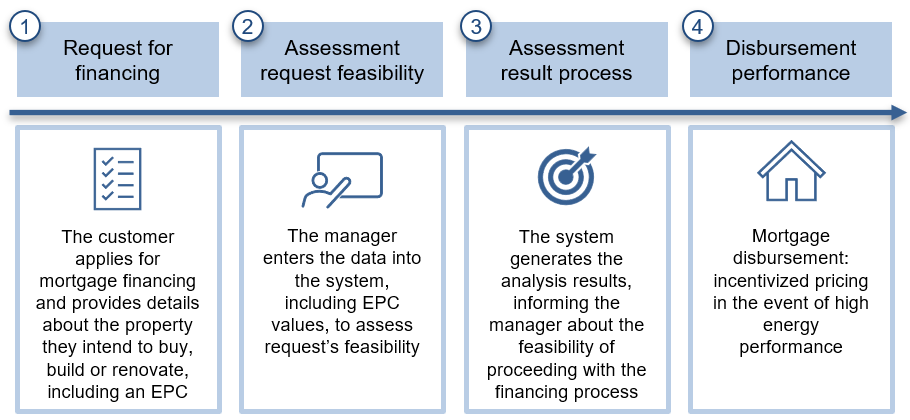

By way of example, banks have introduced mandatory requirements for EPC collection in their mortgage origination process and implemented a set of IT requirements in July 2023 to prevent any need for future remediation. It is interesting to note that these requirements automatically block the financing request procedure if the mandatory EPC information is not present in the IT systems.

Figure 1

Illustrative example of the household mortgage origination process

Source: Bank presentation at the conference.

Once data have been stored in the IT systems they are sent to the EU taxonomy engine to check that they align with regulatory requirements for sustainability. The result of the calculation is received by the sustainability portal, which stores the information and forwards it to the reporting system for the purposes of disclosure.

The above is just one example, but all the banks invited to the conference were following the same path. And it was not only these banks – most of the banks included in the targeted review of residential real estate lending conducted by the ECB in 2022 were also doing so. Those few banks that were not yet doing so were asked to update their loan origination policies and develop an appropriate IT system.

Focus area 2: good practice for key energy performance data points from EPCs

On top of digitalisation, another key element to consider is the type of data collected at loan origination. The EPC class or label may not be the best indicator of a building’s energy efficiency. Indeed, the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive has based its targets on the energy use of buildings in an attempt to overcome national differences in the calculation of EPC labels.

It is essential to collect underlying data points which are effectively the building blocks of the final “label” or energy “class”[4]. Date of EPC expiry and issuance, year of construction and energy consumption are useful data that banks already store in their IT systems. In practical terms, the EPC expiry date could be used to set an alert in the system which would signal when expiry is imminent, the year of construction could be used to gain an idea of the buildings that require renovation and the floor size could be used to assess transition risk as well as physical risk. In line with the annex to the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, EPCs will be standardised in all countries so that, as a minimum, their templates will display energy performance class, the calculated annual primary and final energy use in kWh/(m2y), the calculated annual primary and final energy consumption in kWh and the renewable energy produced onsite as a percentage of energy use.

Collecting energy performance data points at loan origination brings a lot of value. In addition to helping banks comply with the relevant regulation, it also allows them to build up internal data series that can then be utilised and modelled for credit risk management and business development purposes.

Success means overcoming challenges

While the banks at this conference focused on what was working well and how they had overcome challenges, it is important to recognise that there are also challenges at loan origination, as illustrated in the following examples.

- As EPCs have validity terms, they could be out of date. A certificate expires after ten years, along with the information it contains. Customers have no incentive to pay again for a new certificate unless they want to sell their house. Indeed, an EPC is only mandatory for customers looking to sell.

- In some countries it is expensive for borrowers to obtain EPC certificates and/or the EPC certification process is separate from the property valuation process, making it cumbersome and unattractive to customers.

- In some countries borrowers do not always understand why they need to provide a certificate and banks find it difficult to convince customers to do so.

National governments and agencies have a material role to play in ensuring that the process is as efficient and cost-effective as possible. Given the size of real estate-guaranteed assets on the balance sheets of banks, if EPC information is commonly available and understood as a natural part of the loan origination process, this will help smooth the way to a more carbon-neutral economy.

Banks have taken a proactive approach to this topic because they recognise that it makes no sense at all to focus solely on the final energy label or class. Instead, a more granular perspective should be adopted by collecting and storing the underlying fundamental data points. As explained above, ECB Banking Supervision considers this approach to be essential.

Accordingly, ECB Banking Supervision will continue to assess the extent to which banks do not yet collect energy performance data at loan origination for the CRE and RRE sectors. Supervisors will take remedial action to help further level the playing field and improve consistency across countries and banks under European banking supervision.

A mix of strategies to fill the data gap for existing stock

For the existing stock of real estate on banks’ balance sheets there is unfortunately no one way forward when it comes to closing data gaps. Banks will need to be open-minded and actively try different solutions to achieve success.

Banks highlighted the following.

- Progress is possible! Banks explained that a board that is committed to tackling climate-related risks can reap success. They acknowledged that even though challenges exist, progress can be achieved through strong governance.

- Combine strategies. Given how complex the issues are, it is essential to implement a wide range of strategies to increase data coverage.

- Innovate. Banks will need to be innovative to encourage customer engagement and find solutions to complex data-sharing and privacy issues.

- Banks can’t do this alone! Given existing major data accessibility issues and the suboptimal solution of having banks investing separately in the collection of the same data, there might be a case for country-coordinated solutions involving governments and agencies.

What solutions are out there for banks?

Ways to close the energy performance data gaps for existing stock that were discussed at the conference included (in no particular order):

- IT

- purchasing data from external data providers

- targeted customer engagement, including renovation loans

- using public data bases

Concrete examples of each of the above are discussed below

1. IT

The banks explained that there can often be substantial EPC information sitting idle in banks’ paper files. This information may have been collected at loan origination, or during customer engagement, before formal IT solutions had been implemented at loan origination.

“Sitting idle in banks’ in paper files” means the information cannot be used, as it is not located in banks’ IT systems or data lakes.

To remedy this situation, some banks created a budget to fund resources and an IT program that uses, for example, sophisticated scanning technology to extract information from the files and transfer it into an IT system.

Adding these data to the IT system, in combination with other solutions, helped to close data gaps.

2. Purchasing data from external data providers

Where data are available elsewhere in the system, external data providers can play a role in closing the gap. For example, in Spain and Italy there are a number of agencies that provide estimated and actual EPC data.

The use of a segmentation approach to prioritise buildings with missing EPCs is particularly noteworthy. Large sets of data can often be broken down into more manageable and homogenous cohorts, leading to better targeted analytics and more effective decision-making. The same process can be applied to a bank’s stock in the case of missing EPCs relating to existing loans secured by real estate. Segmentation can be used to help inform a decision to purchase data from external companies or to use a customer outreach programme.

One example is prioritising existing stock by using specific data attributes and segmenting as follows.

- Property location: in an example case the portfolio was divided into specific regions in which there was a public database. With the help of an external data provider, data were retrieved from the public land registry to match specific collateral addresses that had missing EPC information.

- Residual maturity: in the above case the portfolio was divided into smaller segments by identifying buildings linked to mortgages that had been originated online after 2016. Then external data providers helped to identify the specific details of the collateral. This made it possible to match up properties and download the relevant EPC-related documents. The documents were then extracted and the relevant data points transferred directly into the bank’s IT system.

Where banks purchase data, it is essential that they maintain sufficient oversight. Banks need to understand and challenge the validity and useability of the data they are buying. Ultimately, banks are responsible for their own analytics, modelling and internal processes, so they need to ensure that the data they buy and use are of high quality and are fit for purpose.

3. Targeted customer engagement

Many banks spoke about their experiences of using customer outreach strategies to close data gaps. In general, these strategies have been successful when used in innovative and creative ways. Some approaches discussed were:

- using information already available to the customer

- dividing existing stock into manageable cohorts

- incentivising customers to work with the bank

- offering financial support for renovation works

- educating customers as to why information on the energy efficiency of a building is valuable

Some concrete examples are outlined below.

Using information already available to the customer

Innovative IT technology is useful when a bank already has the EPC data available in paper format. However, it may also be used to target customers who are likely to have valuable EPC information at home. Banks reported that they saw a lot of value in engaging with customers to make sure all available information had been received.

An example from the conference was to implement a customer outreach process. First, a letter and then an email were sent out to all retail clients, asking them to voluntarily send any EPC information already in their possession. Customers were not required to obtain a new EPC: they simply had to send in the information they already had at home.

To make it easy to transfer information, it is important to invest in upgrading IT so that customers can upload a picture of the relevant EPC information via the banking application platform. In the above example, the upgraded IT is used to integrate that information into the bank’s system, thus helping to close data gaps without putting any extra burden on customers.

Dividing existing stock into manageable cohorts

Banks at the conference used also the property location and residual loan maturity to divide up their portfolios. Another way to structure the client outreach programme is to prioritise the oldest buildings (based on the year of construction) or the loans with the highest loan-to-value (LTV). Where banks are faced with very large EPC gaps for existing stock, dividing the book into riskier cohorts, such as higher LTV, can be a useful way to begin the customer outreach process. However, it is not sufficient for banks to focus only on specific cohorts – they should also develop concrete plans for closing EPC data gaps in a timely manner.

Incentivising customers to work with the bank

Incentives are an important tool for improving response rates in client outreach programmes. While it is essential to send letters or emails to customers asking for EPC information, this is sometimes not enough to achieve a good response rate. In fact, banks explained that they had achieved a much higher response rate (65%) when combining outreach with incentives. For example, banks used interest rate discounts, competition prizes or free car leasing contracts. Many banks were very active in this regard and were keen to try out innovative ways to improve response rates still further.

An interesting case was discussed where banks could cover the costs of a real estate building energy performance adviser, who then provided a free service to customers. Banks at the conference spoke about the importance of banks and government agencies, since they play a key role in creating more awareness amongst customers of the many benefits of upgrading buildings.

Offering financial support for renovation works

As seen in one of the earlier examples, year of construction can be used to divide up the portfolio and target clients in an EPC request. However, it could also be used to reach out to clients and offer financial support for building renovation. Improving the energy efficiency of buildings via renovation work is good reason for a new EPC. It could help banks close existing data gaps and support customers seeking to make their homes more sustainable.

Targeted products can also be used to incentivise renovation work and EPC availability. For example, a full renovation package can be offered that provides free, customised energy advice to customers wishing to make their homes more sustainable and upgrade their EPC class. It can target customers who already have a mortgage with the bank and a home which has an energy label of E, F or G. The strategy has been extremely successful as it has contributed to around 13,000 new definitive energy label registrations in only six months.

4. Using public databases

There are differences between European countries when it comes to data accessibility. In some countries (e.g. France and Portugal) there is a public national database, while in others, such as Belgium, Spain and Italy, the database is at the regional level (although not all regions provide data). Where a database is available, banks can download information and, for example, match it with a customer address. A good example of downloading and matching data is explained below.

- First, a list of properties is created without an EPC. The list contains the data to be researched, namely the complete address of the property and its identification number. All properties that are exempt by law are removed.

- The list is placed in a repository to be accessed by a bot.

- The bot obtains the corresponding EPC data and document from the public database.

- The bot is run once per month to automatically updates the bank’s database and archives the document.

Accessibility and availability of energy performance information for the stock of real estate

Based on the outcomes of previous ECB targeted reviews and this conference, the main obstacles to improving climate-related data coverage are data accessibility and availability and their variation across countries.

For example, the Dutch statistics institution holds information on energy efficiency for 60% of Dutch buildings, while in Spain availability is below 30% and for the Baltics States the figure is even lower. With regard to data accessibility, Germany does not have a public register, Luxembourg is working on a database and Italy has only limited coverage (with only five regions out of 20 included).

Energy performance labels and class definitions vary by country. However, as discussed earlier in this article, there are some underlying data points which can be thought of as building blocks. Banks are very keen to obtain these.

Key information points such as building location, year of construction and floor size are already collected by banks via their collateral valuation procedures. At the time of writing, almost all banks have comprehensive sets of collateral information built into their IT systems for easy retrieval.

Another important data point is energy consumption, which is often not available in banks’ collateral stock. However, energy consumption for individual properties is known, as it is held in utility companies’ IT systems. If this information, in some form, was accessible to banks (noting and respecting of course the legal boundaries of the General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR), it could be added to other key collateral information to produce a meaningful energy efficiency estimation for buildings. This is, however, much harder in practice than it sounds. Given that information on properties’ energy usage and demand is held by utility companies, possible information sharing workarounds could be discussed in the future to harness that information in a manner that is legally acceptable but does not breach customers’ privacy. Conference participants discussed how additional information could be provided for missing EPCs. Suggestions included asking utility companies to provide aggregate energy consumption data in a manner that would not breach data privacy, and analysing payments made to utility companies at an aggregate level from current accounts in an automated manner that, once again, did not breach data privacy.

The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive has already brought positive change, even if it has not yet been transposed into national law. A European database is, however, a long way off.

Banks will need to play their role, but this is not something they can do on their own. An orderly and timely transition of government and national agencies’ actions would be advisable to facilitate cooperation, as climate change is already taking a heavy toll.

Fewer obstacles for commercial real estate

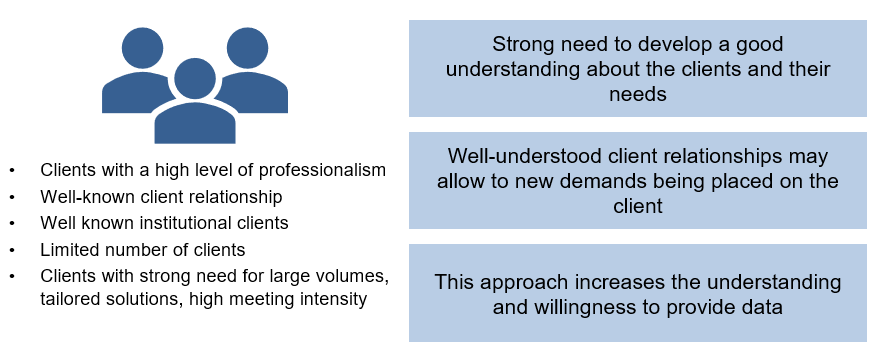

Comparing residential real estate (RRE) and commercial real estate (CRE), it might seem that CRE should be the easier nut to crack in terms of closing EPC data gaps.

However, in practice, the amount of EPC data known by banks is lower for CRE than for RRE. Indeed, as of December 2023 banks know 22% of actual data for CRE compared with 29% of actual data for RRE.[5] Including estimations, on average the amount of unknown data for CRE stands at 44%, higher than for RRE which stands at 26%.[6]

Some of the positives raised at the conference were:

- the solid relationship built with clients: CRE is more often managed through a relationship manager while retail follows a mass volume approach

- the regularity of manager/client engagement: CRE is often subject to more regular bank reviews than RRE which, once the loan has been advanced, is not usually reviewed unless there are signs of distress

- better knowledge and awareness of real estate investors than individual consumers

- reduced privacy restrictions for businesses compared with individuals

- more regularity/higher frequency of CRE collateral valuations due to regulation

- fewer exemptions in terms of applicable buildings for CRE compared with RRE

- shorter rollover periods for CRE than for RRE; CRE loans are often much shorter (five to ten years) than RRE loans, which can extend to over 35 years in some countries

Conference participants agreed that the key to good data coverage is client selection, a client relationship built on tailored financing solutions and an early start to data collection.

Figure 2

Illustration of a successful CRE strategy

Key success factor is the client relationship

Source: Bank presentation at the conference.

Since CRE poses fewer obstacles to data collection, ECB Banking Supervision expects more banks to focus actively on improving coverage of real energy performance data for their CRE books.

Physical risk: mitigants are required to cover damage from more frequent hazard events

Physical risk is a different story and comes with different challenges. One of the consequences of climate change is more frequent hazard events – this is nothing new. These events are not predictable. Banks at the conference explained that data on hazard events are often bought from external providers. The data are incorporated into banks’ own data on property location so that assets can be geolocated and matched with hazards.

As regards the collection of energy performance data, it should be easier to manage physical risk for commercial buildings as banks can take greater advantage of client relationships to mitigate and tailor this risk.

For the collection of physical risk data, banks need as a minimum the address of a building so they can match it with a zone subject to specific hazard events and calculate its physical risk score. However, this is not the only important variable to consider – another example mentioned at the conference was floor data for buildings. While most information – and certainly the address of a building – is internally available, other data on hazard events needed to calculate the final score are provided by external companies.

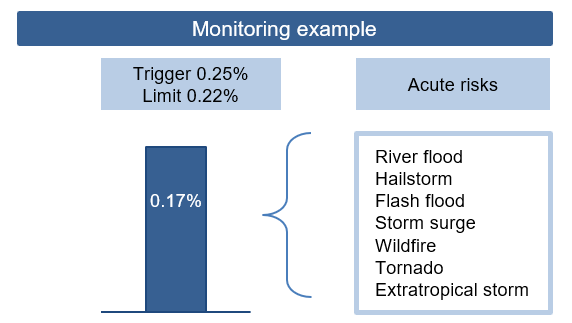

By way of example, a physical risk indicator could be calculated as follows.

- All relevant hazards are identified and assessed with the support of an external data provider. Five scores (ranging from very low to very high) are defined based on materiality thresholds and the expected frequency of the hazards. The bank considers seven acute hazard events, as listed below.

- Information on the location of real estate collateral is available in the bank’s system, although other data, such as surface or floor data for the apartment, are not always available in the system.

- For each relevant hazard, the expected yearly damage is calculated considering (i) the frequency of the hazard at post code level, (ii) the damage per square meter of surface by geography or type of asset, and (iii) the collateral surface. Considering that data on the surface and the floor of the apartment are not always available in the bank’s system, the bank introduced a floor and a cap for the ratio of expected damage.

- The physical risk indicator is then calculated as the ratio of the damage estimated as per above to the total fair value of the bank’s collateral.

- This is then included in a monitoring dashboard and integrated into credit processes to avoid any trigger or limit breaches.

Figure 3

Illustrative example of physical risk score monitoring

Including the physical risk score in the Risk Assessment Framework dashboard is the first step towards ensuring proper visibility

Source: Bank presentation at the conference.

Note: The numbers above are not real: they are only an example for illustration purposes.

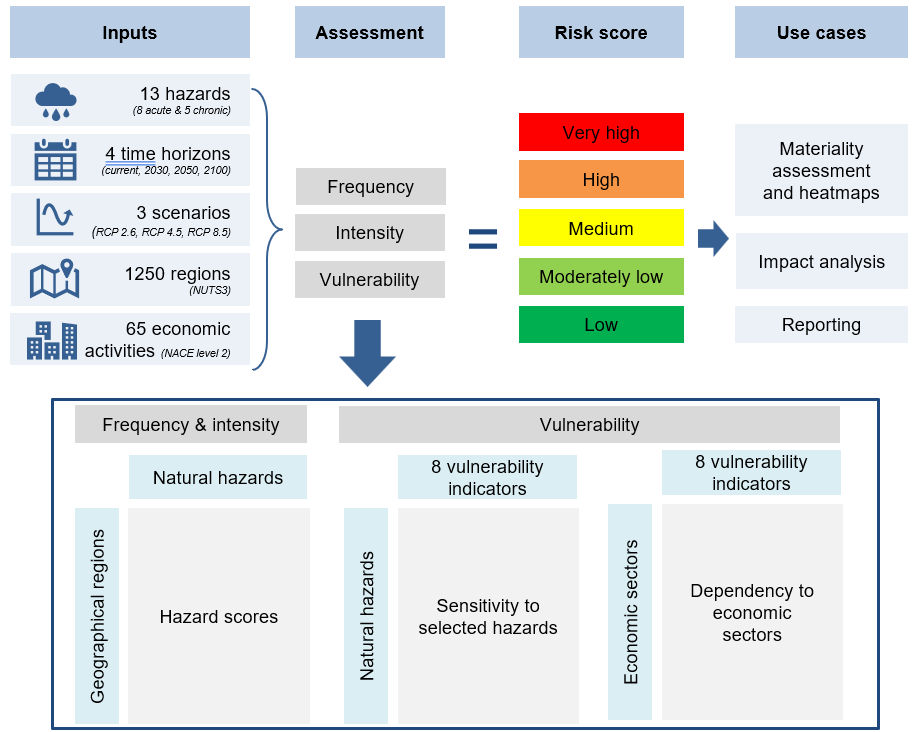

Alternatively, the address can be used to geolocate an asset and external data providers are helpful to obtain other inputs including data on hazard events, time horizons and scenarios. However, in another example from the conference, the physical risk indicator was built by considering both physical risk caused by extreme events (as flood or drought), and physical risk caused by progressive shifts, such as a rise in sea levels. These data are required to perform an assessment based on frequency, intensity and vulnerability and obtain a score from “very high” to “low”. The physical risk score is then used for disclosure, impact analysis and materiality assessment. The detailed methodology is explained in the figure below.

Figure 4

Illustrative example of physical risk score methodology

Source: Bank presentation at the conference.

Physical risk is then mitigated at asset level via insurance collected by clients and at portfolio level via diversification and forward-looking analysis. As per ICAAP guidelines, banks are required to perform the risk identification on the gross exposure. Therefore, as banks confirmed at the conference, the identification of bank’s exposure to physical risk is performed without consideration to mitigation actions, that is without insurance – which makes the final physical risk score calculated by banks a gross score. On the other hand, insurance should be considered when assessing the potential financial impact for risk management purposes. However, there is a mismatch between time and mitigants, which ultimately makes it difficult for banks to calculate the financial impact. Insurance policies are annual, meaning that customers can change or update their policies every year. It is challenging for banks to stay up to date as they would need to ask their customers for new information every year.

Insurance was a topic of keen discussion at the conference with participating banks noting that insurance companies, the major counterparty in damage coverage, are:

- changing clauses in contracts to adjust the number of hazards included in covered events

- increasing the premium paid by the customer

Insurance companies are looking to decrease their cash outflows, but the question remains: if insurance is not going to pay for damage, who is? Banks participating in the conference called for more national protection schemes to cover the gap left after insurance.

Banks are also facing more challenges on physical risk. The lack of harmonisation in the definitions and accessibility of data on physical risk makes comparability of data difficult among banks. Indeed, looking at definitions, for example flood risk is a general category, which could refer to river or coastal floods. Banks can use their own definitions in assessing physical risk and they can use individual selections, such as a differing number of hazard events or different type of hazard events. In the two examples above, in one case only extreme events were considered (the so-called acute physical risk), in particular seven types of extreme events, while in the second case eight extreme events, but also five chronic risks (such as the rise in sea levels or temperature), were included for inputs. The input heterogeneity does not only refer to the hazards, but also to scenarios and time horizons. All the above leeway for banks makes outcomes and assessments harder to compare between banks. Regarding the accessibility of these data, there is still no common repository where all banks can access the same information and the same definition of physical risk for each hazard event. Therefore, banks seem to rely considerably on external companies to ascertain how much of their portfolio bears a high physical risk. Purchasing these data is also a material cost for banks. Another challenge is the fact that restricting capital flows based on physical risk could lead in an increase in the vulnerability of assets and negatively impact the real economy. Therefore, mitigants are expected to play a major role, but as already seen, there are constraints and challenges with that.

More challenges have been extensively discussed with the European Banking Federation and a report has been recently published on physical risk.

Conclusions and next steps

While this article focuses on existing challenges, it also highlights the fact that progress is possible if specific action is taken and innovative strategies are implemented. If banks remain idle they will find themselves unable to adequately measure and monitor the growing risks on their balance sheets. The history of banking has shown that early and proactive action reaps rewards and leads to competitive advantages.

- For new business, it is essential for EPC data collection to be well integrated as part of the loan origination process. It is expected by supervisors.

- For existing stock, active engagement and a will to implement a combination of strategies are key.

- Physical risk is a reality, so banks need to actively measure and monitor this risk.

It is also acknowledged that there are still many national obstacles to data accessibility and availability. Banks cannot deal with this alone.

A timely transition of national governments’ actions would be preferred over a scenario of doing too little too late, to implement policy changes that foster cooperation and make a real difference.

The banks invited to the conference have been very proactive in searching for solutions and their experiences and success stories could help other banks to navigate their own way forward. However, these banks should not stop there but push for even more results. Banks who have identified successful strategies can also act as multipliers by sharing their experiences. This will help other banks to develop their own plan to close data gaps.

From a supervisory perspective, unwillingness to take concrete actions or complacency to ‘wait and see’ will not be acceptable.

ECB Banking Supervision is committed to this topic and will continue to engage actively with banks to push for a level playing field on this very important topic.

“Real estate climate data industry good practices”, ECB summit, Monday, 23 September 2024, Frankfurt am Main.

Share of actual energy performance certificates for residential and commercial real estate based on a range of supervisory activities.

See the 2022 climate risk stress test report published in July 2022.

The most important data points to collect and store are the following: EPC label, EPC date of expiry and issuance, EPC data source, EPC rationale (i.e. major renovation), building year, total energy consumption in kWh/(m2y), total energy use in kWh/(m2y), renewable energy produced onsite as a percentage of energy use, CO2 emissions (kg/m2), heated/cooled surface area, and floor.

Source: Supervisory data – short term exercise data collection as of December 2023 as well as aggregated data at EU level from banks under European banking supervision and subject to the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process.

Source: Supervisory data – as per above.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts