- SPEECH

Financial integration in the Baltics: lessons in resilience and transformation

Keynote speech by Claudia Buch, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the International Financial Markets Conference organised by the Ministry of Finance of Lithuania, Lietuvos bankas and the Lithuanian Banking Association

Vilnius, 4 October 2024

This year we are celebrating the tenth anniversary of European banking supervision under the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM).[1] With the SSM and the banking union more broadly, Europe has demonstrated its ability to respond to crises in a united way – with greater harmonisation and integration rather than retreating to national solutions and fragmentation. A lot has been achieved in the past ten years in terms of enhancing resilience, reducing risks, and applying common rules and supervisory standards.

But these achievements pale in comparison to the transformation and integration witnessed in the Baltic region. Over the past 30 years, the Baltic states have gone through an unprecedented process of institution-building following the disintegration of the former Soviet Union. There has been a massive economic transformation in response to changes in relative prices and an almost complete reorientation of trade flows. Accession to the European Union and the adoption of the euro around ten years ago have been the most visible symbols of this transformation.[2]

Progress has been impressive. While the GDP per capita of the Baltic states was around one-third of the euro area average in the mid-1990s, it has now reached two-thirds.[3] In many areas, the Baltics are leading the way in terms of the digital transformation. They have attracted foreign direct investment, know-how and capital inflows. And their banking markets are closely integrated, in particular with the Nordic region.

But the Baltics have also experienced the downside of integration. In the run-up to the global financial crisis, inflows of capital fuelled a real appreciation of their currencies and an unsustainable credit expansion. When cross-border capital flows suddenly stopped, the region had to weather the storms of the global financial crisis, and it went through a painful recessionary period. Real wages declined and unemployment increased.[4] Flexibility in the real economy made it easier to adjust to changes in relative prices.

The Baltic experience holds important lessons.

First, financial integration and resilient banking systems make a key contribution to economic transformation. The entry of foreign banks into the Baltic countries has improved the quality of financial services and financed economic growth. Following the crisis, foreign-owned banks opted to remain in the region, rather than withdraw, contributing to the recapitalisation of the sector and facilitating the clean-up of balance sheets. Their shift from wholesale intragroup funding to more resilient local funding further supported the recovery.

Second, financial integration needs to be accompanied by strong and harmonised regulation and supervision. The post-crisis reforms and the creation of the banking union have made important contributions by establishing common rules and supervisory standards, introducing essential safeguards against the build-up of risk, and further enhancing trust in the financial system. The Baltic region has benefited greatly from these institutional changes.

Third, the digitalisation of financial services can further enhance financial integration and development, but it also demands robust safeguards to address associated risks. Digitalisation facilitates the cross-border provision of financial services, reducing the importance of regional proximity. While this brings many benefits, it also introduces risks through cyberattacks or money laundering, that must be addressed by banks. Moreover, the EU can make further progress in establishing a more secure foundation for financial integration. Among the key priorities, the European crisis management framework should be strengthened and a European deposit insurance scheme is needed to complete the banking union.

The upside: economic transformation and financial integration

Over the past 30 years, the Baltic region has gone through an unprecedented period of economic transformation and financial integration. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania have navigated the complex path from centrally planned Soviet economies to market economies, eventually becoming full members of the European Union, the euro area and the banking union. This transformation was not without its challenges, requiring deep adjustments and imposing costs on the population. Economic transformation requires broad societal consensus around a willingness to endure the inevitable hardships.

In the Baltics, there was indeed a strong consensus to embrace the reforms necessary for EU membership in 2004. Euro adoption followed in 2011 in Estonia, 2014 in Latvia, and 2015 in Lithuania. Estonian and Latvian banks came under European supervision at its inception in 2014, with Lithuania following a year later.

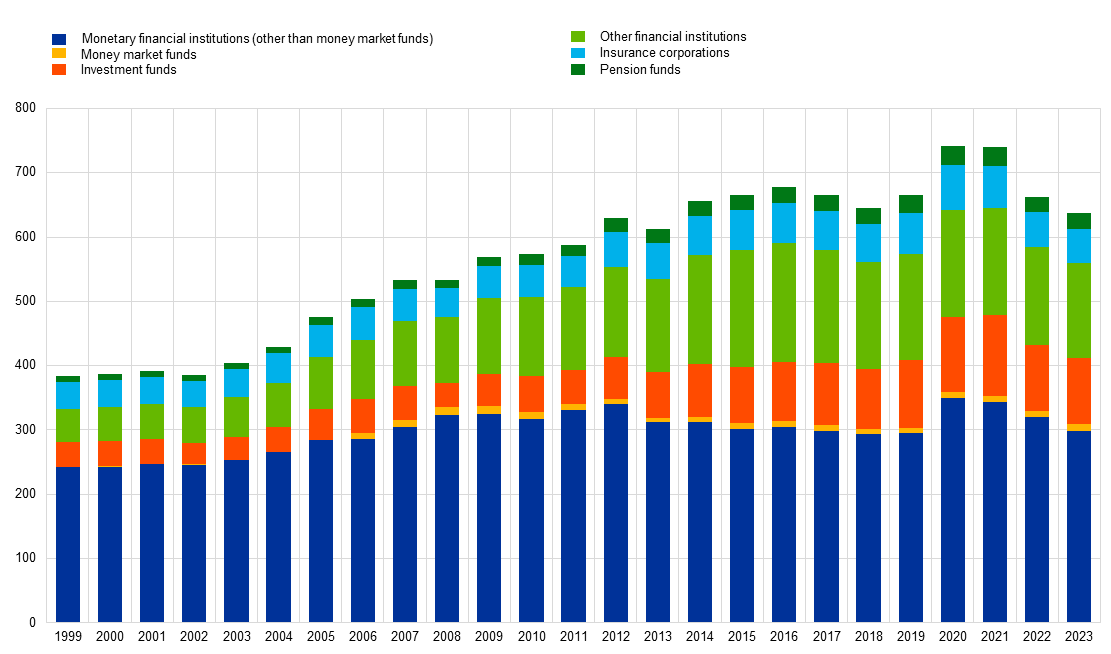

Banking sectors have developed rapidly. The Baltic banking sector has grown substantially, with total banking assets accounting for more than 130% of GDP in 2023 (Chart 1),[5] compared to around 30% in the mid-1990s.[6]

The 1990s were characterised by banking sector instability and consolidation. Economic transformation left its mark on banks’ balance sheets and banks were burdened with non-performing loans (NPLs). Moreover, the Ruble crisis of the late 1990s had negative spillovers into the region.

Chart 1: Total financial assets relative to GDP

a) EU

(ratio to GDP in percentages; annual data, 1999-2023)

b) Baltic States

(ratio to GDP in percentages; annual data, 1999-2023)

Sources: ECB quarterly sector accounts, balance sheet items and main aggregates, and national accounts (MNA) statistics.

Governments in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania opened up their markets to foreign ownership. Assets held by foreign-controlled banks increased significantly up until the financial crisis and have remained elevated in the post-crisis period. In 2020 foreign-owned bank assets accounted for 80% in Estonia, 86% in Latvia, and 91% in Lithuania.[7]

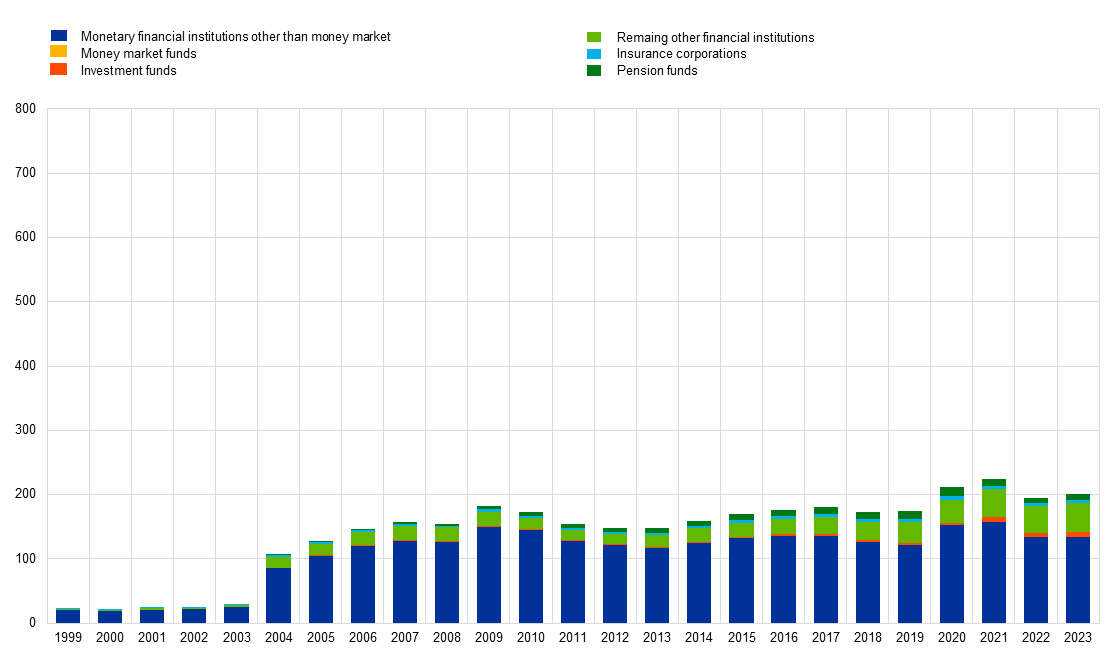

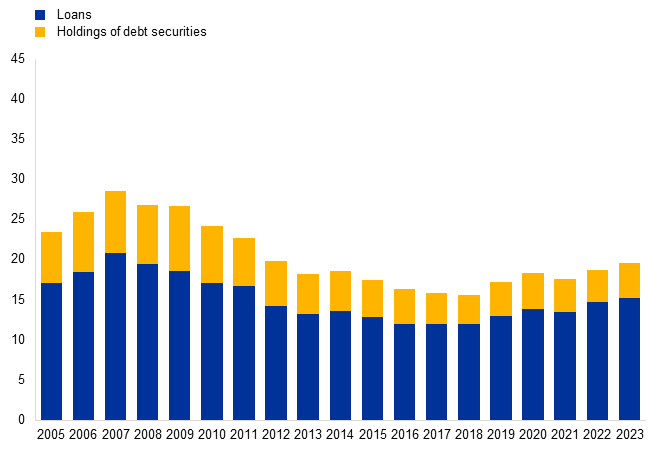

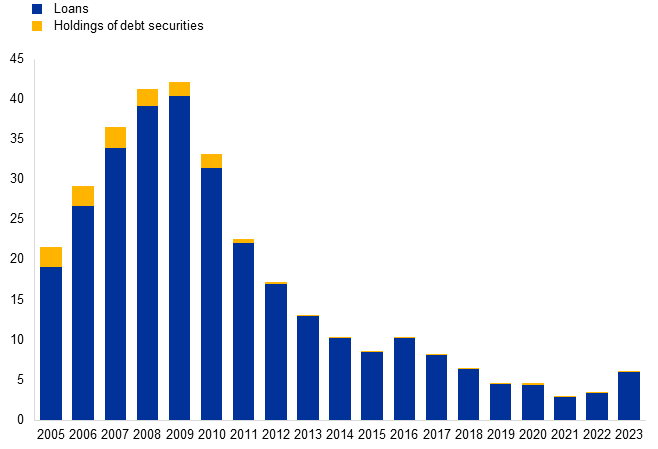

Initially, interbank markets integrated strongly across borders (Chart 2). In the Baltics, loans from non-resident banks, combined with their holdings of debt securities, more than doubled in proportion to GDP between 2005 and 2009.

Chart 2: Interbank financing through non-resident banks

a) EU

(ratio to GDP in percentages; annual data, 2005-2023)

b) Baltic States

(ratio to GDP in percentages; annual data, 2005-2023)

Notes: Panel a) shows the connections between monetary financial institutions (MFIs) from all EU countries where Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are not included as counterpart areas. Panel b) shows the connections between MFIs from all EU countries where only Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are included as counterpart areas. Values are normalised by GDP in both panels.

Overall, up until the early 2000s, economic integration and transformation progressed. GDP per capita was increasing, capital inflows were strong, productivity improved, and EU accession promoted the transformation of institutions. Foreign bank ownership brought with it expertise, credibility, and funding from groups’ parent entities. Before adopting the euro, the Baltic countries had pegged their currencies against it, with limited room for exchange rate adjustments. Across the region, levels of public debt were well within the Maastricht criteria.[8]

Yet at the same time, vulnerabilities were building up in the financial system. These vulnerabilities were eventually exposed during the global financial crisis. Banking markets became dependent on the financial health of foreign parent entities, real estate markets showed signs of overvaluation, and real exchange rates appreciated, gradually eroding the competitiveness of firms in the small, open Baltic economies.[9] Overoptimism about future productivity growth and the benefits of EU accession may have further fuelled these developments, with growth ultimately proving unsustainable.

The downside: the sudden stop of cross-border capital flows

Due to their exposure to cross-border capital flows, the Baltic economies were severely impacted by the global financial crisis. Banks came under funding pressure, largely because of their heavy reliance on intragroup liquidity. Lending in the interbank market came under strain, and credit conditions worsened. Exports dropped, and capital flows came to a sudden stop.

Similar sudden stops happened in other small, open economies. But the situation in the Baltics was special due to the quasi-fixed exchange rates. Abandoning exchange rate stability and devaluing national currencies could have allowed the corporate sector to adjust to external pressure – but only at the cost of losing the hard-won credibility of fiscal and monetary prudence. This dilemma was less acute in other European periphery countries which had access to the enhanced liquidity provision provided by the Eurosystem.[10]

The burden of adjustment fell on real wages and labour markets. This ultimately enabled the Baltic economies to regain competitiveness, but it also required painful adjustments in the real economy. While the specific patterns differed across countries, unit labour costs were lowered through a combination of lower nominal wages, layoffs and increases in productivity.[11] Because of the lack of additional shock absorbers, adjustment was faster than in countries that had access to Eurosystem liquidity.[12]

The Baltic economies fell into deep recessions. The cumulative output loss in 2008 and 2009 was around 18% in Estonia, 21% in Latvia and 12% in Lithuania,[13] and unemployment rates increased to between 15% and 20% in 2010.[14] Governments implemented structural reforms to alleviate the effects of the crisis. Non-performing loan (NPL) ratios increased up to 20% in Latvia and Lithuania, and up to 5% in Estonia.[15]

Foreign-owned banks active in the Baltic region downsized activities but did not withdraw in the aftermath of the crisis. While reducing their reliance on intragroup funding, they remained active in these markets. These foreign-owned groups bolstered the capital positions of their Baltic subsidiaries and played a key role in the swift resolution of NPLs. Better-capitalised subsidiaries were better equipped to provision for risks and resolve NPLs. The resolution process was further facilitated by group-wide asset management company strategies being rolled out to foreign subsidiaries.[16]

Banking union: rebuilding resilience and strengthening supervision

Europe learned vital lessons from the global financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis. In an integrated banking market, national supervision alone cannot address cross-border risks. With the banking union, supervision of the largest banks has been moved to the European level and a framework for the resolution of banks has been established. But the third pillar of the banking union – a European deposit insurance scheme – is still missing.

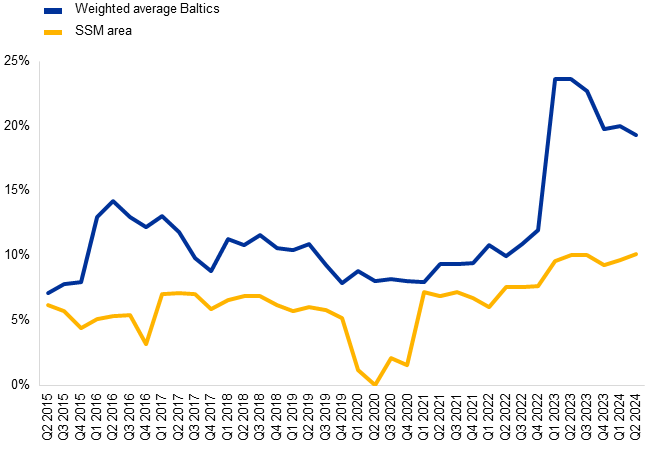

One lesson learned from the crises was that bank capital needs to be strengthened in order to boost resilience. Baltic banks have in fact been strongly capitalised from the start of the banking union (Chart 3). In 2015, the average Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio of Baltic banks stood at over 28% – more than twice the average of European supervised banks of less than 13%. Currently, capital ratios in the Baltic region remain above 20% compared with a banking union average of slightly less than 16%. Similarly, the profitability of Baltic banks has been higher, with an aggregated annualised return on equity of 20% compared with an average of close to 10% in the first quarter of 2024.

Chart 3: Capitalisation and profitability of banks

CET1 ratio for significant institutions

Return on equity for significant institutions

Source: ECB supervisory banking statistics

Strong micro and macroprudential supervision have underpinned this resilience. Integration of the region’s banking systems into European banking supervision has contributed towards high supervisory standards. Active macroprudential policies have helped maintain financial stability. Capital-based measures, such as countercyclical buffer requirements and buffer requirements for systemically important banks, are complemented by borrower-based measures and risk weight measures targeted at systemic risks arising in the real estate sector.[17]

The strong role played by banks from other Nordic countries requires that supervision is closely coordinated across countries. Nordic-Baltic cooperation in banking supervision and macroprudential policy is primarily facilitated through the Nordic-Baltic Macroprudential Forum established in 2011. In addition, the Nordic-Baltic Stability Group, established in 2010 to enhance coordination and preparedness for potential financial crises, brings together finance ministries, central banks, financial supervisory authorities and resolution authorities from the Nordic and Baltic countries. It conducts financial crisis simulation exercises to test and improve the region's ability to respond to complex, cross-border banking crises.

Despite this close integration, financial systems in the Baltics have some distinct features. The five largest credit institutions have a market share of around 90% in the Baltics compared with an EU average of 68%. The relatively small size of markets may be one explanation, as fixed entry costs weigh more heavily than in larger markets. Each country has specific regulations and legal frameworks in place that govern, for example, insolvency procedures or mortgage lending. These factors create fixed costs to enter the market.

Chart 4: Banking markets in the Baltics are relatively concentrated

Source: ECB structural financial indicators as at 2023.

The Baltics’ financial sectors are relatively small compared to GDP. For Europe as a whole, growth in financial markets occurred predominantly in non-bank financial intermediation. The Baltic financial sector, in contrast, is dominated by banks with two-thirds of financial assets. Across the EU, banks and non-bank financial intermediaries hold similar amounts of assets.

The future: integration and development through digitalisation

Over the past 30 years, financial integration in the Baltic region has had a strong regional component. The next phase of integration could be less reliant on regional proximity. The region is, in many ways, leading the way in digitalisation. For the provision of digital financial services, borders and physical infrastructures matter less. This provides new opportunities as well as new challenges.

The Baltic economies are highly digitalised, which is clearly reflected in their financial services sector. Numerous fintech companies are based in the region, many of which offer payment services, often to non-residents. In Lithuania, for example, the number of fintech licences increased from around 40 to 140 between 2015 and 2021, although it has declined somewhat since then.[18]

This rapid growth in digital financial services also brings risks. Fintechs, like any other financial institution, must have a good understanding of regulatory and supervisory demands related to consumer protection, fraud, and cybersecurity as well as compliance with financial sanctions and AML/CFT rules. Digital banking business models must be supported by investments in risk management, particularly in managing third-party risks and risks associated with digital strategies.

Generally, European banking supervision has identified banks’ digital transformation activities as a supervisory priority. Based on the principle of technological neutrality, the SSM has updated its methodological toolbox[19] by defining criteria for the assessment of digitalisation strategies and collection of sound practices.[20]

The ECB monitors risks related to digitalisation from a prudential perspective. While not all fintechs fall directly under the ECB’s supervision, national competent authorities play a crucial role in overseeing these entities. Together, the ECB and national authorities ensure robust supervision across the region, coordinating their efforts to address emerging risks in the sector. Across the Baltic region, the growth of the fintech sector has led to increased regulatory oversight, particularly in relation to money laundering and terrorist financing risks.

Cyber risk is a growing concern for the Baltic region, as geopolitical tensions and digitalisation expose financial institutions to cyber threats. The ECB’s recent cyber resilience stress test assessed European banks’ readiness to recover from a cyberattack.[21] Generally, banks have response and recovery systems in place. But the test also highlighted areas for improvement in protecting critical functions and customer trust, and the results emphasised that banks must further invest in cutting-edge cybersecurity technologies and build a culture of cyber resilience. Moreover, there is close cooperation across the region to address cyber risk. The European Systemic Risk Board’s (ESRB) recommendation to set up a pan-European cyber incident coordination framework is being implemented to ensure information is shared across borders.

The Baltic region has significantly stepped up its capacities to counter money laundering and financial crime. A series of banking scandals between 2018 and 2020 highlighted weaknesses in national anti-money laundering (AML) frameworks.[22] In response, local authorities have made substantial improvements, enhanced their supervisory capacities and introduced tighter enforcement measures. These efforts contributed to the establishment of the Anti-Money Laundering Authority (AMLA), which centralises and strengthens oversight across the EU. Violation of anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) rules can indeed seriously undermine the reputation and viability of financial institutions. The ECB works closely with national authorities to strengthen AML/CFT measures and participates as an observer in AML/CFT colleges. It also ensures that the implications of AML/CFT risks are properly addressed in ongoing supervision, authorisation and fit-and-proper procedures.

Looking ahead: promoting further integration

Strengthening the resilience of European banks and promoting integration have been two key objectives of the banking union. When banks operate across borders, consumers and firms can truly reap the full benefits of the Single Market. For financial institutions, cross-border activities and mergers can provide opportunities to generate economies of scale and scope. To realise these benefits, banks must have sound risk management practices and strong governance in place. From a prudential perspective, the ECB assesses the prudential and governance implications of mergers, using the same criteria for both domestic and cross-border mergers.[23]

The Baltic region serves as an interesting case study in the cross-border integration of banking markets. As small, open economies requiring deep economic transformation, the countries in this region pursued a focused strategy of fully integrating into the European Single Market and allowing foreign access to their banking sectors. At the height of the global financial crisis, the region faced a sudden withdrawal of capital flows, but its banking sector was able to recover, largely thanks to the response of foreign banking groups. Today, banks in the region maintain strong capital buffers. This financial resilience, together with a strong operational resilience, is crucial in the current phase of heightened geopolitical risk.

The next phase of integration will be increasingly digital, rendering regional proximity less relevant. This makes the establishment of a European deposit insurance scheme all the more urgent. For consumers, such a scheme would provide reassurance that deposits with domestic banks are protected by the same standards as deposits with non-resident banks. In addition, risks associated with digital transformation require close attention of banks and supervisors.

The Baltic region’s experience offers a compelling case for broader European integration of financial markets through the capital markets union (CMU). A key element of CMU is the harmonisation of national rules and regulations that currently serve to effectively segment financial markets. Prime examples include national insolvency legislation or national rules affecting mortgage markets. CMU would also help innovative European firms gain access to equity financing and promote private risk-sharing, both in the Baltics and across the whole euro area.

I am grateful to Jonathan Beißinger, Pascal Busch, Massimiliano Rimarchi and John Roche for their assistance in preparing this speech. All errors and inaccuracies are my own.

Buch, C. (2022), “30 years of monetary reform in Estonia: Lessons learned for the decade ahead”, keynote speech dedicated to the 30th anniversary of monetary reform in Estonia, Deutsche Bundesbank, Frankfurt.

IMF Country Report No. 24/285 Latvia, (2024).

The Baltic region’s adjustment to the sudden stop of capital flows during the global financial crisis has been documented widely. See, for example: Gros, D. and Alcidi, C. (2015), “Country adjustment to a ‘sudden stop’: Does the euro make a difference?”, International Economics and Economic Policy, Vol. 12, pp. 5-20; Hansson, A. and Randveer, M. (2013), “Economic Adjustment in the Baltic Countries”, Working Paper Series, No 1, Eesti Pank; and Kang, J.S. and Shambaugh, J. (2014), “Progress Towards External Adjustment in the Euro Area periphery and the Baltics”, Working Papers, No 14/131, IMF.

ECB quarterly sector accounts, balance sheet items and main aggregates, and national accounts (MNA) statistics.

Eesti Pank (1995), “Financial Intermediaries”, Annual Report; International Monetary Fund (1999), “Republic of Lithuania: Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix”, IMF Staff Country Reports, No 99/96.

Baudino, P. et al. (2022), “The 2008 financial crises in the Baltic countries”, FSI Crisis Management Series, No 3.

ECB (2008), Convergence Report, May.

Hansson, A. and Randveer, M. (2013), op. cit.

Buch, C., Buchholz, M., Lipponer, A. and Prieto, E. (2017), “Liquidity provision, financial vulnerability, and internal adjustment to a sudden stop”, Deutsche Bundesbank (mimeo). See also Deutsche Bundesbank (2016), “The influence of central bank liquidity provision on internal adjustment to a sudden stop”, Monthly Report, September, 50-52.

See, for example, Blanchard, O.J., Griffiths, M. and Gruss, B. (2013), “Boom, Bust, Recovery: Forensics of the Latvia Crisis”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, pp. 325-388; and Kang, J.S. and Shambaugh, J. (2014), op. cit.

Hansson, A. and Randveer, M. (2013), op. cit.

Staehr, K. (2013), “Austerity in the Baltic states during the global financial crisis”, Intereconomics, Vol. 48, No 5, pp. 293-302.

International Monetary Fund (2024), “Republic of Latvia: 2024 Article IV Consultation – Press Release and Staff Report”, IMF Staff Country Reports, No 24/285, p.9.

Baudino, P. et al. (2022), “The 2008 financial crises in the Baltic countries”, FSI Crisis Management Series, No 3.

Ibid.

See “Overview of national macroprudential measures” on the ESRB website.

Lietuvos bankas (2024), Financial Stability Review, p.47.

McCaul, E. (2024), “A key step in assessing SSM banks’ digitalisation journey and related risks”, The Supervision Blog, ECB, 11 July.

European Central Bank (2024), Digitalisation: key assessment criteria and collection of sound practices.

European Central Bank (2024), “ECB concludes cyber resilience stress test”, press release, 26 July.

McNaughton, K.J. (2024), “The tale of the Baltics: Experiences, challenges, and lessons from reforming their national Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs)”, Journal of Economic Criminology, Vol. 5, September.

In 2021 the ECB published a Guide on the supervisory approach to consolidation in the banking sector, which outlines supervisory expectations in this area.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts