Speech by Andrea Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the EUROFI 2023 Financial Forum organised in association with the Spanish Presidency of the Council of the EU

Santiago de Compostela, 14 September 2023

Introduction

It is my pleasure to be here with you today – my last time attending the Eurofi conference as Chair of the ECB’s Supervisory Board.

I would like to pay tribute to Jacques de Larosière, who set up Eurofi in 2000 as the European think tank dedicated to the integration of European financial markets. And to David Wright and Didier Cahen, who continued the pursuit of providing a space for an open and candid debate between market participants and policy makers on European financial regulation and supervision.

I have benefited greatly throughout my career from the opportunities for dialogue that Eurofi provides. We had a lot of fruitful discussions around the creation of the European Supervisory Authorities and the banking union. And since the global financial crisis, Eurofi has hosted an ongoing debate between regulators and the banking industry on the myriad regulatory reforms that have been proposed, discussed and implemented.

Much of this debate has pivoted, in one form or another, on how much capital banks ought to maintain in order to be safe and sound while continuing to support the economy. At the risk of oversimplifying, banks have always argued for lower capital requirements, and supervisors and regulators have always argued for higher.

Today I will humbly suggest that we put this debate to bed. As the final Basel III standards are now becoming part of the rulebook across the G20, both the industry and supervisors need to move on from the capital calibration discussion. Instead, as the turmoil episodes in March this year showed, supervisors need to focus more on the effectiveness of supervisory action. It is in the banks’ own interest to engage with us in this debate.

Capital advocacy

I want to start with a recap of the various stances that the banking industry has taken over the years in its advocacy efforts to contain capital requirements.

After the very first Basel III reform package was published in 2010, some in the industry claimed that the newly proposed regulations would precipitate some sort of economic disaster. The quantification of the cumulative impact of the changes on banks’ capital needs led industry bodies to warn of very damaging macroeconomic consequences, with a severe and long-lasting recessionary impact on global GDP and employment.

These arguments did not convince policymakers, who continued to support the tightening of the capital framework based on the solid body of theoretical and empirical research showing that the benefits of banks funding themselves with more capital greatly outweighed the possible costs.[1] Having a larger buffer of loss-absorbing capital reduces the chance of banking crises, which are historically associated with substantial economic costs. It also smoothens the negative impact of economic downturns when they inevitably occur, through allowing banks to lend in more sustainable way through the cycle. Studies showed that, while higher capital requirements potentially lead to higher costs of intermediation, these only have a small long-run impact on the borrowing costs faced by bank customers. As such, they do not offset the benefits of enhanced financial stability.[2] Nonetheless, the concerns raised by the industry did lead to a more gradual phasing-in of the new requirements.

A second battlefield was then opened up in the EU around so-called European “specificities” – supposed special features of our banking structures, markets and products that would justify significant deviations from international standards. This line of argument never made sense to me, as the specific features of EU banking markets are accounted for in the international standards, as a result of lengthy negotiation processes where several EU authorities sitting on the Basel Committee have a say. Empirical evidence has shown that prudential capital discounts targeting specific lines of business or categories of borrowers are not effective in promoting lending.[3] Deviations from international standards do reduce the safeguards for bank stability, while their benefit in promoting our “special” way of financing the economy is far from proven. Nonetheless, this argument proved much more successful and led to material departures from the internationally agreed yardstick. As a result, the Basel Committee assessed the implementation of the Basel capital standards in the EU as materially non-compliant.

Finally, the industry has more recently turned its focus to international comparisons, making the argument that capital requirements are more demanding in the EU than in other jurisdictions, in particular the United States. They argue that the excessive conservatism of European regulators and supervisors makes the European banking industry less competitive on the global stage. The implication is that public authorities should look at capital requirements as a lever of international competitiveness to support their banks in the face of competition from banks in other regions.

I disagree with this on principle. International standards provide a common minimum floor to avoid regulators using less stringent requirements as a way of favouring national champions, but there should always be room for supervisors to apply higher requirements if they believe these are warranted by the risk profile of the banks under their responsibility. But more than that, the attempts to compare capital requirements internationally face major methodological challenges and might easily lead to unproductive discussions. So let me clarify some aspects of the much-discussed EU-US comparison, before moving on to what I think should be more solid and productive grounds of debate between banks and prudential authorities.

International comparisons

Comparing capital requirements across different jurisdictions is a complex task. The industry analysis that I have seen reaches what on the surface appear to be very clear-cut conclusions, but does so on debatable technical grounds.[4] First, there is an issue of sample selection. And second, the methodology may prove to be too simplistic.

The industry analysis compares the risk-based capital ratio of all European banking union significant institutions with that of large and mid-sized US banks accounting for a comparable level of total assets.[5] With that methodology, you do indeed find that the requirements for European banking union banks are slightly higher.[6]

Chart 1

Aggregate comparison of required CET1 risk-based capital ratios for banking union Significant Institutions and US large and mid-sized banks, as of Q4 2022

(Percentages)

Sources: for US banks, calculations on data from Federal Reserve Consolidated Financial Statements for Holding Companies - FR Y-9C, Federal Reserve Large Bank Capital Requirements 2022 (August). For banking union banks: calculations on COREP data and NCAs notifications to the ECB. The banking union sample includes 110 Significant Institutions; the US sample includes 34 banks which were stress tested by the Federal Reserve in 2022. Required capital ratios are weighted averages, with Risk-Weighted Assets as weights.

But the European sample includes many smaller banks than the US sample.[7] In fact, we should expect that smaller European banks tend to face slightly higher requirements under Pillar 2 than larger US banks, to compensate for their lower risk diversification. We also know that only the largest US banks are subject to full Basel standards, unlike in the EU where Basel standards apply to all banks.

When we break those aggregate samples down, a more nuanced picture emerges.

Take the global systemically important banks (G-SIBs). We can see it is the US G-SIBs that are subject to the higher required ratios. On the other hand, if we compare the other European banking union significant institutions with US banks of a similar size, it is the European banks that face the higher required ratios.

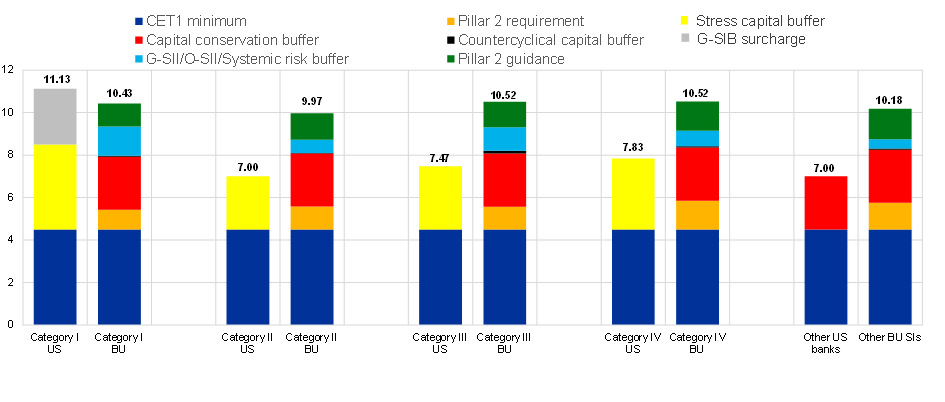

Chart 2

Required CET1 risk-based capital ratios for banking union Significant Institutions and US banks, compared by US bank category size, as of Q4 2022

(Percentages)

Sources: for US banks, calculations on data from Federal Reserve Consolidated Financial Statements for Holding Companies - FR Y-9C, Federal Reserve Large Bank Capital Requirements 2022 (August). For banking union banks: calculations on COREP data and NCAs notifications to the ECB. The banking union sample includes 110 Significant Institutions; the US sample for Categories I to IV includes 34 banks which were stress tested by the Federal Reserve in 2022, while the last column for US banks applies to the other, smaller US banks. Required capital ratios are weighted averages, with Risk-Weighted Assets as weights. The allocation of banking union Significant Institutions into Categories is based only on the total assets criterion and does not take into account other indicators used in the US rules such as, for example, cross-jurisdictional activities or off-balance-sheet exposures.

However, comparing required ratios does not tell us the full story, even if we use like-for-like samples. Several factors are actually at play here: different requirement levels can be the result of different rules and different supervisory approaches, as well as different levels of balance sheet riskiness.

The more relevant question to ask is: would European banks face lower requirements under the current US prudential framework?

Answering this question boils down to imagining a counterfactual scenario and making quite a few assumptions. Because of this, I do not want to make too much of the precise results, but I think the general picture coming out of this comparison holds. We have been looking into assigning the European banks to the size buckets adopted in US legislation, applying the US rules to them and mapping them into a “stress capital buffer” that is proportional to their risk profile, so as to include the Pillar 2 dimension in the analysis.[8]

When we perform this analysis, the tendency in the results seems consistent and goes in the opposite direction to the industry narrative. Relative to their actual requirements today, we find the average requirement for European banking union significant institutions as a whole would be somewhat higher under the US rules.

The requirements would be significantly higher for the European G-SIBs, while they would be lower for most medium size and smaller European banks in the sample.

What drives this result? If we set aside the US gold-plating of international standards in the area of G-SIB buffers and leverage ratio requirements, this result stems from the way in which risk weighted assets are calculated. Here, EU legislation has several downward adjustments relative to international standards, including the non-compliant application of the Basel I floor, which plays a key role in making the EU framework less demanding. Meanwhile, the US rules related to the Collins amendment impose a strict floor based on the standardised approach for credit risk.

Throughout the negotiations to finalise the Basel III reforms, as well as in the run-up to the political agreement that will implement those reforms in the EU, I have heard European banks claim that any form of standardised floor is particularly costly for them because, unlike the US banks, they hold all of their mortgage portfolios on balance sheet, and cannot offload the bulk of their mortgages to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

But we haven’t seen convincing evidence to support that view. On the contrary, under the very simplifying assumption that the European G-SIBs could offload the lion’s share of their mortgage portfolios, our analysis finds that they would still face higher requirements under the current US rules in the counterfactual scenario.

The guiding star of global standards

Leaving the numbers aside, let me go back to principles. The focus on the comparison between EU and US requirements – and the intensity of the clash between banks and regulators on how capital requirements are calibrated – also reflects a bias. A bias that capital is the be-all and end-all of prudential supervision.

This bias prevails on both sides of the argument.

For banks, huge efforts are deployed to develop technical arguments and obtain reductions of capital requirements that are often worth a few basis points. For supervisors, there may be an underlying concern that even the higher capital requirements resulting from the post-crisis reforms might be gradually eroded by industry practices, and in a crisis could prove insufficient to ensure a smooth exit from the market, especially for large and complex banking groups. Indeed, respected academics such as Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig[9], advocate for a much higher level of capital requirements and are sceptical about the magnitude of the effects on the financing of the economy.

However, after a decade-long international debate, the final Basel standards are now being implemented in all jurisdictions based on a sound international agreement that has been subject to much discussion. We should now all accept that these international standards provide our guiding star. And we should put our efforts into ensuring that we effectively apply the regulatory framework that resulted from the implementation of these standards in each G20 jurisdiction.

Yes, there are local variations. First, jurisdictions decide on the scope of application of the standards. The current discussion on the US regime applicable to regional banks has brought this issue of scope back on everyone’s mind. Second, jurisdictions are entitled to impose stricter requirements. Third, and much more worryingly, jurisdictions do make non-compliant choices, like the EU has repeatedly done. This is undesirable and damaging. To avoid the latter, I would personally prefer an international agreement leading to a direct and automatic implementation of Basel standards, or at least a key subset of them, into the regulatory framework of participating jurisdictions. This should follow a process with political safeguards similar to the one designed in the EU for the implementation of international accounting standards. But so long as the implementation follows very diverse processes across jurisdictions, we have to accept that deviations remain possible and, alas, likely.

Now the final Basel 3 implementation is close to completion in all jurisdictions of the G20, it is time to close this chapter of the discussion and live with the globally agreed rules that we have. The turmoil of March 2023 clearly showed that it is in the interest of both banks and public authorities to now focus the debate on where the focus of supervision should be best placed.

Beyond capital

The banking crises of March 2023 have taught us invaluable lessons. Capital cannot fix a broken business model, nor can it remedy deficient internal governance. These crises shed light on the stark reality that in times of uncertainty and structural change, such as those that characterise the ongoing global monetary policy tightening, both investors and depositors might very rapidly and abruptly shift their focus away from the traditional metrics of bank prudential resilience. And on the basis of assessments centred on economic – rather than regulatory – valuations and on the sustainability of business models, they might withdraw their support to specific institutions. When that occurs, a clear gap opens up between regulatory and market yardsticks and even high capital levels and liquidity buffers can be insufficient to prevent a run on deposits leading to a bank’s failure.

Silicon Valley Bank and some other US regional banks were highly exposed to traditional interest rate risk. The surprising feature of these failures was the speed and coordination with which depositors reacted to the banks declining economic value triggered by very large amounts of unrealised losses on securities held to maturity.

In the case of Credit Suisse, a long stream of episodes that highlighted excessive risk taking, weaknesses in internal controls and concerns about the ability of the bank’s governing bodies to restore profitability to sustainable levels finally led investors and depositors to rapidly withdraw their support.

High regulatory capital and liquidity requirements help in making failure less likely and do help in the resolution process if a bank eventually has to exit the market. But they cannot be the only tool to prevent banking crises. The effectiveness of the supervisory process is crucial. In a recent paper, Bruce Tuckman traces what I think is a key distinction between preventive, detective and punitive supervision.[10]

The first type of supervision relates to is preventive requirements. This involves putting in place standardised regulations applicable to all banks or specific subsets of them. This can include capital and liquidity ratios, stress testing, and standards for governance, controls, and risk management. The primary aim of preventive supervision is to curtail the discretion of banks in areas considered detrimental to individual bank stability and that of the broader financial system.

The second type of supervision is detective evaluation. In this role, supervisors closely examine individual banks, both to gauge the extent to which they are adhering to preventive requirements and to detect any practices that, while not explicitly infringing upon established rules, might undermine bank safety or systemic stability. The aim here is to unearth nuanced risks that might elude the rigid bounds of regulation.

The third type of supervision has to do with corrective action. When issues surface during the detective evaluation phase, this supervisory function comes into play. Its mandate is to compel banks to rectify any problems that have been detected. Supervisors should be able and willing to draw on a wide range of tools to achieve this, which include bank specific additional capital and liquidity requirements, business restrictions, board member reassessments and removals, sanctions and other penalty payments.

The entire discussion on the level of regulatory capital requirements and liquidity buffers is about preventive requirements. But we need to focus much more on detective evaluation and corrective action.

At the ECB, we have made considerable efforts since the banking union was established to put in place and maintain a strong evaluation function. We flagged the risks that rising interest rates would pose for the financial system, and we already incorporated these risks into our supervisory work programme already at the end of 2021, when the first inflationary pressures started to emerge. We made it a priority to ensure that supervised banks were adequately prepared to manage the impact from interest rate and credit spread shocks and to adjust their risk assessment, mitigation and monitoring frameworks in a timely manner, to focus on the economic value perspective and not only on the earnings one. Governance, another root cause of the March 2023 turmoil, is another area where we stepped up our detective activity.

Admittedly, just like other supervisors, we need to improve when it comes to corrective action. To ensure that the banks remediate problems in a timely manner once they have been identified, it is important that we can expeditiously use all the instruments available to us. Bank-specific capital add-ons are an important instrument at our disposal, but in some cases these are not effective enough in compelling banks to take the necessary corrective actions. We need to start using the full toolkit. And equally as important, we are working to foster a culture that encourages supervisors to propose strong actions where they identify weaknesses. This is crucial in areas such as governance and business model sustainability, where too many supervisory findings and measures have gone unaddressed for too long. I acknowledge that these may prove to be sensitive areas for intrusive supervisory interventions, as banks could feel that authorities unduly interfere with managerial responsibilities. But properly communicated measures, within a clearly defined escalation process, are essential to ensure that shortcomings are promptly remediated and the safe and sound management of the bank is restored.

So let’s move on from the debate on the calibration of capital requirements. Let’s implement the international standards we have all agreed on. And let’s focus on making sure that banks take the right corrective actions to address the shortcomings that their supervisors identify. It is in banks’ own interest to engage with us in in this endeavour and make sure that, the next time market confidence dwindles, no weak links can be identified.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2010), An assessment of the long-term economic impact of stronger capital and liquidity requirements, August; Macroeconomic Assessment Group (2010), Assessing the macroeconomic impact of the transition to stronger capital and liquidity requirements, August; Santos, A. and Elliott, D. (2012), “Estimating the Costs of Financial Regulation”, IMF Staff Discussion Notes, No 12/11, International Monetary Fund, September.

Miles, D., Yang, J. and Marcheggiano, G. (2012), “Optimal Bank Capital”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 123, No 567, pp. 1-37.

See, for example, Oliver Wyman and the European Banking Federation (2023), The EU Banking Regulatory Framework and its Impact on Banks and the Economy, January.

In other words, the US banks that are subject to stress tests.

This result only holds true when we include the Pillar 2 Guidance that we set for banks in the EU. Pillar 2 Guidance has no equivalent in the US framework – it is an amount of capital that we expect EU banks to maintain above their regulatory buffers, but which they are allowed to use without incurring automatic consequences in the form of restrictions on distributions. If we instead base our comparison on the point at which binding distribution restrictions are triggered, the US required ratios are stricter even at this aggregate level.

The threshold for qualifying as a significant institution is much smaller than the threshold for inclusion in the US stress test

As defined by their scores in the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process.

Admati, A.R., DeMarzo, P.M., Hellwig, M.F. and Pfleiderer, P.C. (2013), “Fallacies, Irrelevant Facts, and Myths in the Discussion of Capital Regulation: Why Bank Equity is Not Socially Expensive”, October.

Tuckman, B. (2023), “Silicon Valley Bank: Failures in “Detective” and “Punitive” Supervision Far Outweighed the 2019 Tailoring of Preventive Supervision”, in Acharya, V.V. et al. (eds), “SVB and Beyond: The Banking Stress of 2023”, NYU Stern Business School, August.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts