Supervisory methodology - 2019

Introduction

The following sections provide a broad description of the SREP methodology applied for SREP 2019 to significant institutions under direct supervision by the ECB (as set out in the SSM Regulation[1] and the SSM Framework Regulation[2]). Compared with similar information made available for previous SREP exercises, these sections elaborate further on the content already published in the “SSM SREP Methodology Booklet” and the SSM Supervisory Manual.

The ECB carries out the SREP assessment based on a case-by-case approach using a standardised methodology applying a business and corporate governance‑neutral principle.

The SREP approach:

- develops, along the lines of the European Banking Authority (EBA) Guidelines on SREP (EBA/GL/2014/13, as amended)[3], relevant Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV)[4] provisions as transposed into national laws as well as relevant Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR)[5] provisions and other relevant EBA guidelines and regulatory technical standards as applied to the relevant risks assessed within the SREP;

- is periodically updated to keep alignment with the EBA Guidelines on SREP and to reflect new regulations; to keep up with evolving practices, the SSM SREP draws on leading practices within the SSM and as recommended by international bodies, thereby ensuring continuous improvement;

- is applied in a proportionate manner to significant institutions, taking into account the nature, scale and complexity of their activities and, where relevant, their situation within a group.

For official definitions and further information, please refer to the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

1 The Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process

1.1 Executive summary

Teams made up of supervisors from the ECB and national competent authorities (so-called Joint Supervisory Teams (JSTs)) regularly assess and measure the risks for SSM significant institutions. Supervisors carry out this regular review and assessment to determine whether banks are complying with relevant European laws, guidelines and supervisory expectations.

Supervisors do this by carrying out the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process, or SREP, which is central to European banking supervision.

The SREP assesses the way a bank deals with its risks and the elements that could adversely affect its capital or liquidity, now or in the future. This process determines where a bank stands in terms of capital and liquidity requirements as well as the adequacy of its internal arrangements and risk controls.

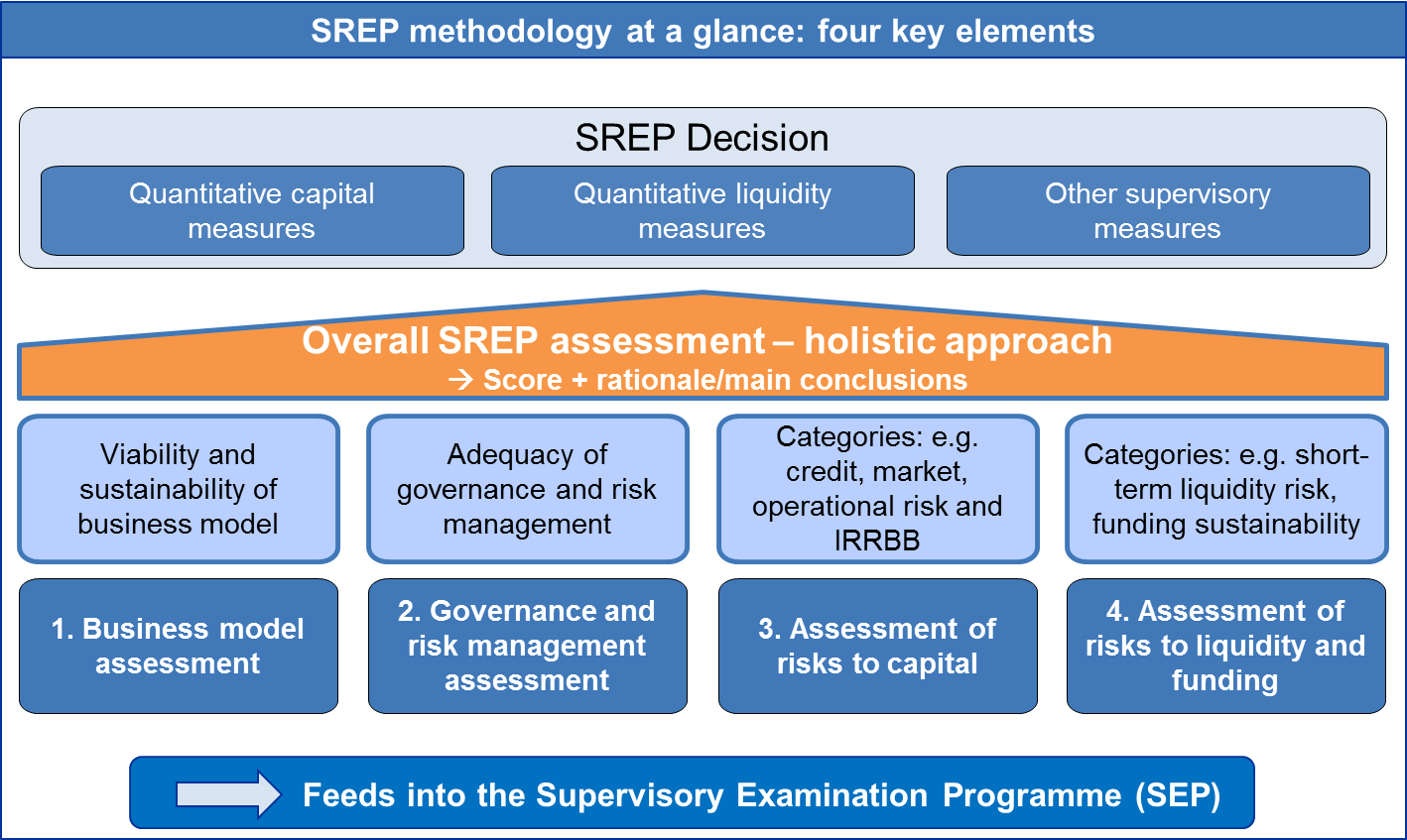

The SREP has three main outcomes:

- a holistic, forward-looking assessment of the overall viability of the institution[6];

- issuance of a decision requiring – where needed – banks to meet their capital/liquidity requirements and implement other supervisory measures[7];

- an input to the determination of the minimum level of supervisory engagement for a specific institution as part of the next Supervisory Examination Programme (SEP)[8].

The SSM SREP is based on four elements:

- A business model and profitability assessment[9];

- An internal governance and risk management assessment[10]

- An assessment of risks to capital[11] on a risk specific basis: i.e. credit risk, market risk, operational risk, interest rate risk in the banking book (IRRBB) and the institution’s internal identified risks in normal scenarios and under stressed conditions. These assessments feed into a preliminary determination of a capital requirement to cover the risks and an assessment of capital adequacy.

- An assessment of risks to liquidity and funding[12] on a risk specific basis: short-term funding, long-term funding, the institution’s internal identified risks in normal scenarios and under stressed conditions. These assessments feed into a preliminary determination of a liquidity requirement to cover the risks and an assessment of liquidity adequacy.

The SSM SREP:

For each element, the evaluation is conducted through a dedicated risk assessment system (RAS). The RAS is fed with regular reporting, such as common reporting (COREP) and financial reporting (FINREP), and qualitative information, and also includes ad hoc information obtained by JSTs from various sources on an ongoing basis. These include other data (e.g. short-term exercise data), reports (e.g. external audit reports), meetings and inputs stemming from on-site supervision and/or deep-dive analysis. The outcome of the RAS is summarised in a rationale and a score that facilitates comparison and internal communication.

The assessment of risks to capital and risks to liquidity and funding (Elements 3 and 4) is performed in blocks and results in the determination of ranges of capital and liquidity requirements – e.g. a total SREP capital requirement ratio (TSCR[13]) or a liquidity coverage ratio (LCR). This assessment is therefore based on the outcome of the ongoing RAS (first block), supplemented by a more comprehensive periodic review of the institution’s capital and liquid positions, in the light of the latter’s own assessments (internal capital adequacy assessment process (ICAAP)/ internal liquidity adequacy assessment process (ILAAP)) (second block), and the supervisor’s own quantifications under stressed conditions (third block).

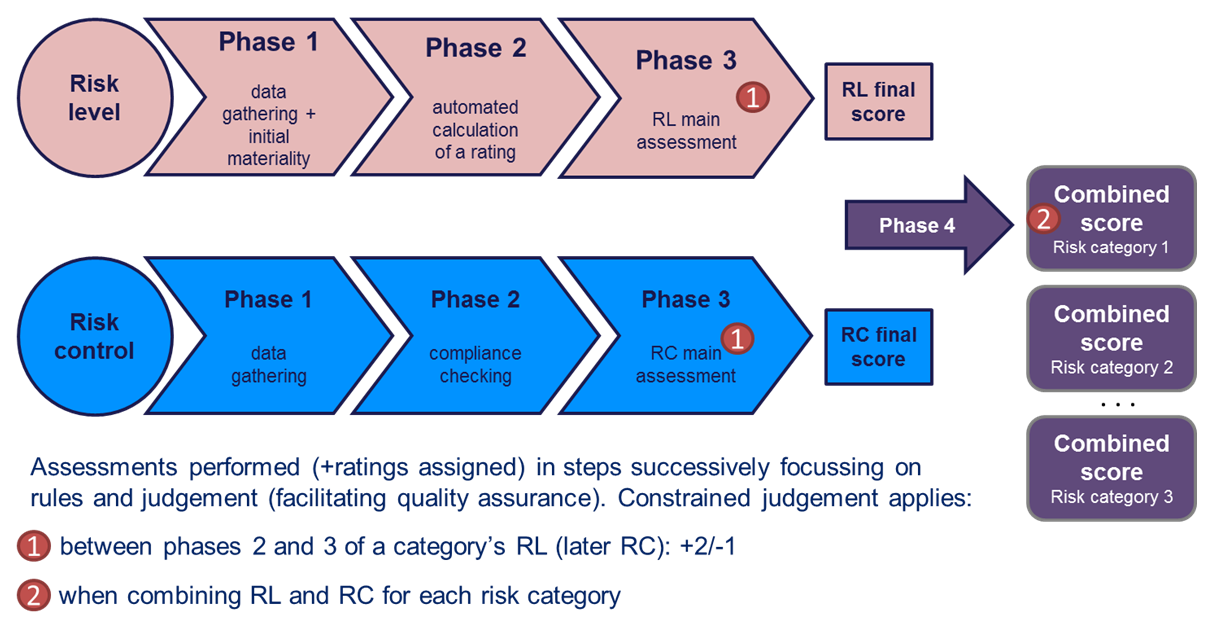

The approach for each of the four elements is based on these three phases focused on either or both a quantitative (risk level[14]) or a qualitative (risk control[15]) perspective in line with the EBA Guidelines on SREP. Following the detailed JST assessment, each of the four elements is given a combined score from a range of “1” (low risk) to “4” (high risk).

The assessment includes the evaluation of the institution’s ICAAP and ILAAP as well as the performance of stress tests.

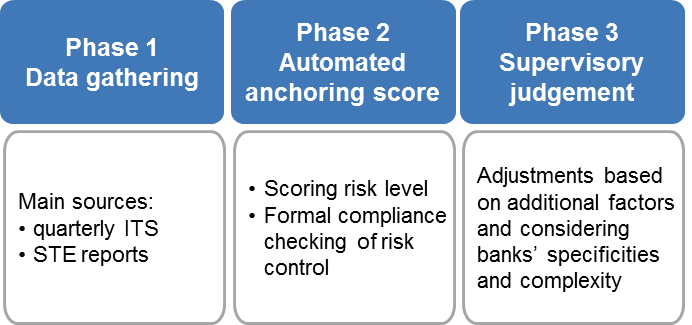

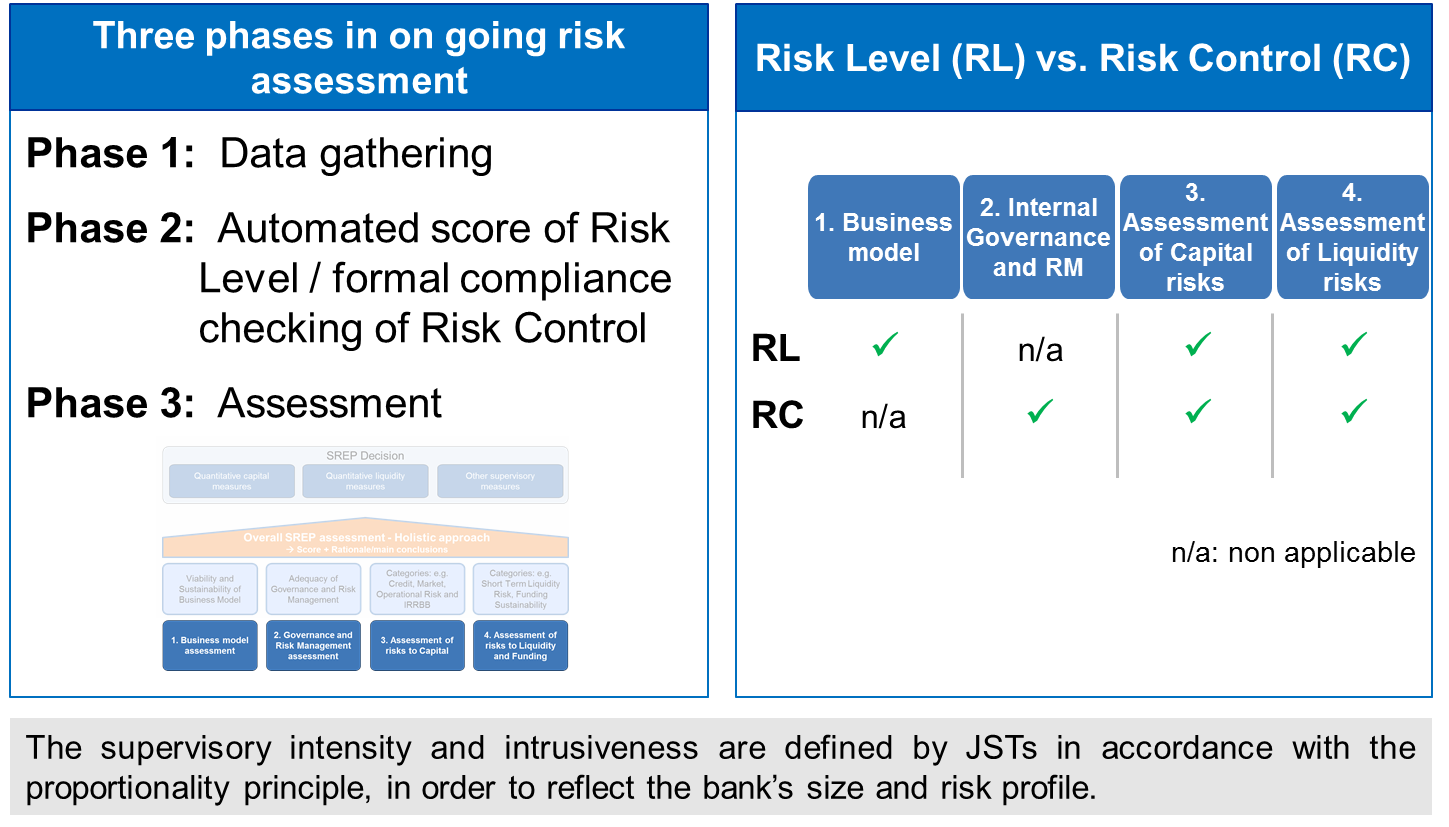

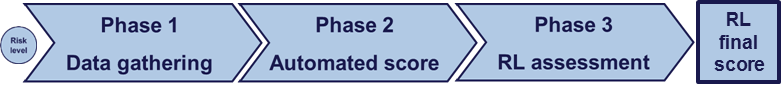

The assessment of each element is performed in three phases:

Phase 1: Supervisors gather data from the bank.

Phase 2: Production of an automated preliminary anchoring score for the risk level and a formal compliance check of risk control.

Phase 3: Supervisors carry out a more thorough risk assessment, taking into account supervisory judgement considering the specificities of the bank.

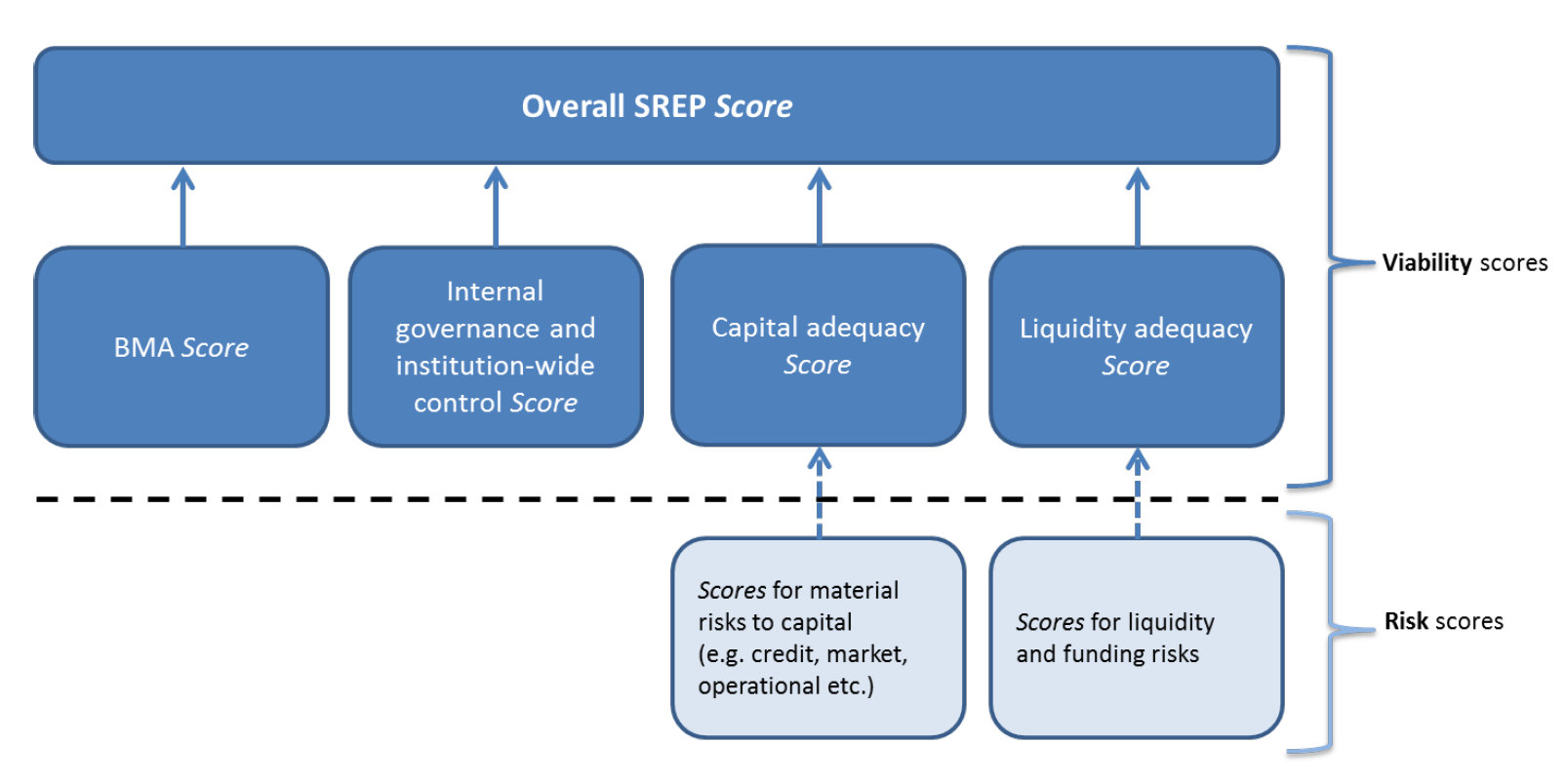

Overall assessment[16]

The assessment of the four elements is then combined into an overall SREP assessment, to reflect the “supervisory view”, which is summarised in the overall SREP score (between 1 and 4) and a main rationale which explains why a certain score is assigned. In line with the EBA Guidelines on SREP, this overall SREP score reflects the supervisor’s overall assessment of the viability of the institution: higher scores reflect higher risks to the viability of the institution stemming from one or several features of its risk profile.

As outcome of the assessment, banks may be asked to implement a wide range of measures to address, if need be, capital and liquidity shortcomings and other qualitative measures.

Banks receive the outcome of the SREP assessment via a formal ECB SREP decision. The individual SREP decision supports other supervisory activities. It feeds into the Supervisory Examination Programme, which consists of strategic and operational planning for the upcoming supervisory cycle. Moreover, it has a direct impact on the frequency and depth of the bank’s off-site and on-site supervisory activities.

2 The framework

The SREP is flexible and adjustable to ensure risk-based supervision. In practice, this means that the frequency, scope and depth with which the elements of the SREP are assessed can vary depending on the level of supervisory engagement and the bank-specific circumstances.

The SREP assessment cycle is generally based on year-end data from the previous year, i.e. the SREP 2019 assessment cycle is generally based on year-end data for 2018. The outcomes of the SREP assessment cycle of a given year generally translate into the SREP decisions applicable for the following year period, i.e. the outcomes of the 2019 SREP assessment cycle are reflected in SREP decisions applicable for 2020 year period.

2.1 Past and forward-looking perspective

The SREP aims to assess an institution’s intrinsic riskiness, its position vis-à-vis a group of peers, and its vulnerability to exogenous factors.

JSTs are required to take all necessary actions in a timely manner to ensure institutions’ future viability, so their assessments also need to take into account a forward-looking perspective. The SREP thus assesses an institution’s viability at a 12-month horizon, in the medium term (three to five years), and over the cycle, by using a wide range of backward and forward-looking quantitative and qualitative information.

Past developments are a key input into the assessment since reliable data are, in general, widely available and they may give an indication about a trend of future developments. This must be complemented by forward-looking information including, for instance, probabilities of default (PDs), loss given defaults (LGDs), institutions’ capital and liquidity planning, and institutions’ and supervisory stress tests. In the RAS, the forward-looking perspective is incorporated under Phase 3 assessments. Block 2 of Elements 3 and 4 takes a forward-looking view with a focus on the near future. Block 3 of Elements 3 and 4 adopts a longer term horizon, e.g. three to five years.

2.2 Holistic approach

The SSM SREP aims to produce an overall picture of an institution’s risk profile that is as adequate as possible, taking into account all relevant risks and their possible mitigates. An institution’s risk profile is necessarily multi-faceted, and many risk factors are inter-related. This also holds true for the possible supervisory actions that can be taken in response. This is why the four elements of the SSM SREP need to be looked at together when producing the overall SREP assessment and preparing the SREP decision.

2.3 Accountability

The SREP results in supervisory actions, including decisions on capital, liquidity or other types of supervisory measures. These measures (immediate, short-term or more structural ones) have to be taken into account in supervisory planning.

The SSM SREP strives to perform high-quality supervision to ensure financial stability within the SSM. This entails enhancing SSM institutions’ resilience to shocks. JSTs will carry out their assessment in a conservative manner, adopting a fair but tough approach, and take the necessary action to enhance and ensure institutions’ viability.

2.4 Constrained judgement[17]

A “constrained judgement” principle applies throughout the SREP, allowing the JST to take into account the specificity and complexity of an institution while also ensuring consistency across supervisory judgements within the SSM. This is done through anchor points provided by the system, from which JSTs can deviate to a certain extent. Both dimensions are important. Anchor points are necessary to ensure homogeneity in supervisory assessments, but they cannot take into account the specificities of an institution’s risks and are considered to be a starting point for the supervisory assessment. Judgement by the JST is necessary to adequately assess an institution’s specific risk profile, but needs to be consistent over time and across institutions.

Constrained judgement in the SSM SREP can be summarised as follows:

- anchor points provide a standardised perspective across institutions;

- all assessments rely on supervisory judgement;

- judgement is guided by the SREP methodology and it is possible to depart from anchor points to a certain, pre-defined extent;

- each step is justified and documented, to ensure accountability.

The constrained judgement should ensure the right balance between:

- a common process, ensuring consistency across SSM banks and defining anchor points;

- the necessary supervisory judgement, to take into account the specificities and complexity of an institution.

Constrained judgement is used effectively by JSTs in both directions – improving as well as worsening the scores.

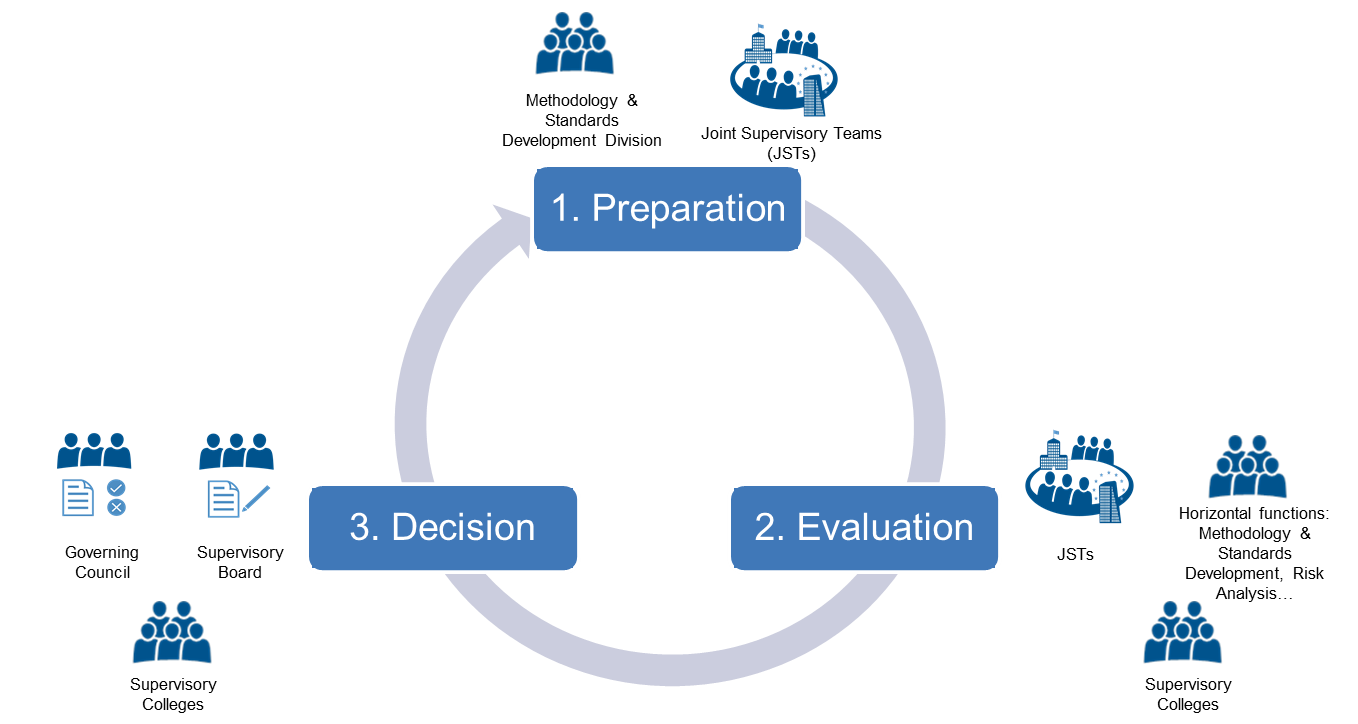

3 The overall SREP process

3.1 Preparation: information sources[18]

The SREP assessment is performed based on a wide range of information sources of a quantitative and qualitative nature. Quantitative data are of particular importance for fostering consistency and comparability.

Key sources of quantitative information include (non-exhaustive list):

- risk indicators based on FINREP and COREP data (available on a consolidated level since mid-2014);

- risk indicators from sources other than FINREP/COREP;

- indicators on economic and market conditions (GDP, sector NPLs, market volatility, etc.);

- other, non-harmonised regulatory data (central credit register, etc.);

- an institution’s internal estimates (ICAAP, ILAAP, stress tests, internal reports);

- financial statements, Pillar 3;

- peer group indicators;

- supervisory stress test results;

- market views (external ratings, investors’ quantitative analyses, etc.).

Key sources of qualitative information include (non-exhaustive list):

- relevant documentation, such as policy documents;

- supervisory findings (inspection reports, meeting reports, etc.);

- institutions’ internal documents (ICAAP/ILAAP, risk appetite, financial statements, management body memos, organisational charts, internal audit reports, whistle-blower reports, etc.);

- business and risk management reports (dashboards, limit reports, etc.);

- reports on the environment in which they operate: risk trends, new areas of focus, analysts’ reports, rating agencies’ reports, equity analyst recommendations, news.

3.2 Evaluation: overview

The SSM risk assessment system (RAS) supports the JSTs’ day-to-day supervisory work. It is used for their ongoing analysis of Element 1 (business model), Element 2 (internal governance and risk management), Block 1 of Element 3 (risks to capital), and Block 1 of Element 4 (risks to liquidity and funding).

Supervisory assessments of the four elements and the overall SREP are formalised in a rationale and a score. In the rationale, the JST highlights the main factors driving its assessment, key deficiencies, and their possible effects on the institution’s viability, supported by key evidence such as tables and figures.

Scores are mostly used as a tool to easily summarise the supervisor’s view and facilitate high-level, cross-sector comparisons and communication, both within the SSM and with the institution itself. They should not be confused with other types of ratings, such as those used by rating agencies or institutions to assess a debtor’s ability to pay back its debt or the likelihood of its default.

Overview of the scoring framework[19]:

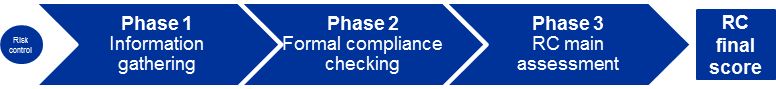

Risk elements are assessed from both a quantitative (risk level[20]) perspective and a qualitative (risk control[21]) perspective.

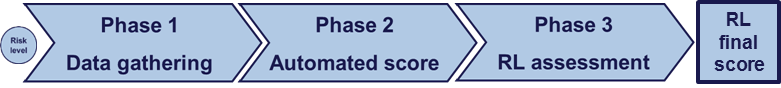

For each perspective, assessments are performed in three complementary phases[22]:

These three phases define a logical sequence to be followed when performing the assessment. In practice, additional information collected during the supervisory activities needs to be recorded on an ongoing basis. The outcome of Phase 3 may also require the JST to gather additional information in order to refine its assessment.

3.2.1 Considerations in relation to inherent risk[23]: risk level

A risk level (RL) assessment refers to the intrinsic riskiness of an institution’s portfolios and takes into account several dimensions: the intrinsic situation and riskiness of the institution, the comparison of its situation with that of a peer group, and macro factors that may influence its risk profile. These dimensions are reviewed in the three‑phase process mentioned above.

3.2.1.1 Phase 1

This information/data gathering phase allows the JST to keep up-to-date information on an institution’s activities, risks and processes. It also serves as an initial identification of the materiality of risk factors and sub-categories to be assessed in Phase 3.

The “materiality” of an institution’s risks is taken into account for two main reasons: i) to identify those activities and risks which are critical for an institution’s ability to ensure sound management and coverage of its risks; and ii) to focus supervisory work and decisions on those activities that entail risks which threaten the institution’s capacity to operate, either in the short term (viability) or in the medium to long term (sustainability), and its ability to cover and manage its risks.

A “material risk” is defined as a risk that would have an impact on the “prudential elements” of the institution if it materialised. The materiality of a risk reflects size and riskiness. Depending on the category, size and riskiness, the materiality is separable (e.g. in the case of credit and market risk), or not (e.g. operational risk).

The materiality of a risk is taken into account at three different levels in the SREP.

i. When assessing business model and profitability

The main activities of the institution are initially reviewed from a holistic point of view in order to identify which activities may threaten the institution’s prudential elements (especially its future profits, its capital adequacy, and its liquidity position).

ii. When assessing the risk level of a risk factor category

Phase 1 starts with a more detailed check to determine whether the category could be considered non-material in special cases. Scores assigned at the end of Phase 3 reflect the materiality of a risk.

iii. When combining risk category scores: the overall SREP score should reflect the institution’s ability to bear and manage its risks (especially the material ones)

The data gathering phase also allows the JST to position an institution against its peers. SSM institutions are classified under nine types of business models, to allow further comparisons. JSTs can also complement their analysis by referring to other peer groups that they deem relevant.

3.2.1.2 Phase 2

This automated anchoring phase proposes an intrinsic assessment based on a number of pre-defined indicators/criteria applied to all institutions in a systematic and comparable way. The objective is to systematically review the situation of an institution against a selection of identical quantitative indicators that the SSM deems relevant, so as to foster assessment consistency within the system.

Each underlying indicator is associated with a score from 1 to 4 corresponding to defined thresholds. Indicators are calculated based on regulatory reporting for availability and consistency reasons. When choosing the indicators and corresponding thresholds, a balance had to be struck between accuracy and simplicity so that they could be applied to a very large population of institutions with different business models. The relevance of the indicators, thresholds and aggregation rules is monitored and back-tested ex post on a regular basis and updated as deemed appropriate.

In all cases, data quality is key for institutions to be able to properly manage their risks and for supervisors to be able to reliably assess institutions.

3.2.1.3 Phase 3

This main assessment phase reviews a wide range of quantitative and qualitative information coming from a wide range of sources to provide a more accurate picture of an institution from a quantitative perspective, and to shed light on its relative position vis-à-vis its peers and the environment in which it operates. This complements the limitations of the standardised assessment performed in Phase 2. Assessments are expressed in a rationale summarising the assessment and a score.

The JSTs then adjust the Phase 2 risk level score on the basis of this Phase 3 intermediate score, following the constrained judgement approach (+2/-1).

3.2.1.4 Common scores for the assessment of risk level[24]

1 = “Low”: there is no discernible risk of significant impact on the prudential elements of the group or its entities considering the inherent risk level.

2 = “Medium-low”: there is a low risk of significant impact on the prudential elements of the group or its entities considering the inherent risk level.

3 = “Medium-high”: there is a medium risk of significant impact on the prudential elements of the group or its entities considering the inherent risk level.

4 = “High”: there is a high risk of significant impact on the prudential elements of the group or its entities considering the inherent risk level.

3.2.2 Considerations in relation to adequate management and controls[25]: risk control

A risk control (RC) assessment refers to the adequacy and appropriateness of an institution’s internal governance/risk management and of the risk management and controls that are in place at the risk factor level. This includes assessing how institutions monitor their risk exposures, identify the measures that need to be taken, and assess the adequacy of their internal policies, organisation and limits.

Category-specific risk control arrangements that are assessed need to be consistent with the general internal governance/risk management at the level of the institution.

The risk control assessment for each category examined consists of three phases.

3.2.2.1 Phase 1

The information gathering assembles relevant data and information on the key features of an institution’s risk control/internal governance environment.

3.2.2.2 Phase 2

This phase checks whether an institution’s internal governance and risk control framework formally complies with the key requirements of the applicable regulation, technical standards and key guidelines issued by the EBA.

For risk controls related to capital and liquidity risks, the focus includes, but is not limited to, four main sub-categories: i) governance, ii) risk appetite, iii) risk management and internal control, and iv) internal audit.

For internal governance, the focus includes, but is not limited to, three main sub-categories: i) internal governance, ii) risk management and risk culture, and iii) risk infrastructure, data and reporting.

In all cases, data quality is key for institutions to be able to properly manage their risks and for supervisors to be able to reliably assess institutions.

3.2.2.3 Phase 3

In this main assessment phase, the JST assesses how the governance and control framework works in practice. This requires reviewing the adequacy of the control and governance framework in the light of the scale and complexity (business model, organisational structure, etc.) of the institution, and the degree to which the framework is embedded in its operational processes.

The JST needs to perform an in-depth analysis of Phase 2 non-compliance areas, notably by considering the following questions (non-exhaustive list).

- What are the reasons for non-compliance?

- Is the non-compliance confirmed and does it constitute a breach of regulatory requirements?

- Are there mitigating factors?

- What can the supervisory response be?

In addition, institutions may formally comply with Phase 2 requirements and still be assigned a high risk score in Phase 3: weaknesses may arise from aspects that were not covered by Phase 2 or, more importantly, control mechanisms may not work properly.

The JSTs assess each sub-category, identifying underlying reasons for the score assigned (key strengths and deficiencies, mitigations and other relevant corrective factors). Their content is meant to be indicative of the type of the assessment required to assign the score.

The ECB has also developed an approach to identify and reflect anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) concerns in prudential supervision.

3.2.2.4 Common scores for the assessment of risk control[26]

1 = “Strong control”: there is no discernible risk of significant impact on the prudential elements of the group or its entities considering the management, organisation and controls. The level of risk management and control is high. The risk management and control framework is clearly defined and fully compatible with the nature and complexity of the institution’s activities.

2 = “Adequate control”: there is a low risk of significant impact on the prudential elements of the group or its entities considering the management, organisation and controls. The level of risk management and control is acceptable. The risk management and control framework is adequately defined and sufficiently compatible with the nature and complexity of the institution’s activities.

3 = “Weak control”: there is a medium risk of significant impact on the prudential elements of the group or its entities considering the management, organisation and controls. The level of risk management and control are weak and need improvement. The risks are insufficiently mitigated and controlled, leaving too high a residual risk. The risk management and control framework is poorly defined or insufficiently compatible with the nature and complexity of the institution’s activities.

4 = “Inadequate control”: there is a high level of risk of significant impact on the prudential elements of the group or its entities considering the management, organisation and controls. The level of risk management and control is very low and needs drastic and/or immediate improvement. The risks are not or are inadequately mitigated and are poorly controlled. The risk management and control framework is not defined or not compatible with the nature and complexity of the institution’s activities.

3.2.3 Combining risk level and risk control assessments[27]

The assessments of a category’s risk level and risk control are combined to provide the category’s “combined assessment”. For Element 3 (risks to capital), the assessments of individual risk categories are subsequently combined using a weighted average to produce an overall capital-related risk assessment.

For each risk category related to capital and liquidity, risk level and risk control scores are aggregated starting from the assumption that risk control assessed as “adequate” (i.e. 2) is “neutral” –therefore in this case the combined score is identical to the risk level score. Some RL-RC combinations require the application of supervisory judgement.

- If risk control is “strong” (i.e. “1”), the JST may choose to assign a combined score that is one notch better than – or identical to – the risk level score.

- If risk control is “weak” (i.e. “3”), the JST may choose to assign a combined score that is one notch worse than – or identical to – the risk level score.

- If risk control is “inadequate” (i.e. “4”), the JST may choose to assign a combined score that is one or two notches worse than the risk level score.

3.2.4 The SREP overall assessment[28]

At the end of the assessment of the four elements, supervisors assign an overall SREP score from 1 to 4. In line with the EBA Guidelines on SREP, this overall SREP score represents a supervisory view of the overall viability of the institution on the basis of the aggregate view of the threats to viability[29].

The overall SREP score should be assigned taking into account the outcomes of the assessment of individual risks: higher scores reflect an increased risk to the viability of the institution stemming from one or several features of its risk profile, including its business model, its internal governance framework, and individual risks to its solvency or liquidity positions.

The JSTs can then adjust this anchoring overall SREP score by applying constrained judgement (possibility to modify the overall SREP score by +2/-1 notches, i.e. reduced by a maximum of two notches or improved by a maximum of one notch based on: i) their knowledge of the institution, ii) peer comparisons, iii) the macro environment under which the institution operates, iv) its capital/liquidity planning to ensure a sound trajectory towards the full implementation of the CRR/CRD IV, and v) the SSM risk tolerance. It may want to reflect in the overall SREP score weaknesses identified throughout the SREP process that it considers particularly important for the institution.

The aim is to provide a holistic assessment of an institution’s risk profile and assess the most appropriate supervisory measures, if needed: own funds requirements, liquidity requirements, or other qualitative supervisory measures.

3.3 Decision: SREP decisions and their communication[30]

3.3.1 SREP decision

The SREP decision is taken under Article 16 of the SSM Regulation and is issued following a hearing (see Article 22(1) and Article 31 of the SSM Framework Regulation). It must be duly reasoned (see Article 22(2) of the SSM Regulation and Article 33 of the SSM Framework Regulation).

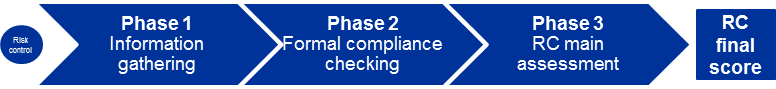

SREP decisions are adopted by the Governing Council through the non-objection procedure on the basis of complete draft decisions proposed by the Supervisory Board and they may include:

Own fund requirements[31]

- Total SREP capital requirement composed of Pillar 1 minimum own fund requirements (8%) and additional own fund requirements (P2R)

- Combined buffer requirements

Institution-specific quantitative liquidity requirements

- LCR higher than the regulatory minimum

- Higher survival periods

- National measures

Other qualitative supervisory measures

- Additional supervisory measures stemming from Article 16(2) of the SSM Regulation include, as an example, the restriction or limitation of business, the requirement to reduce risks, the restriction of or prior approval to distribute dividends, and the imposition of additional or more frequent reporting obligations.

- SREP communication also includes Pillar 2 Guidance expressed as a CET1 ratio add-on.

3.3.2 Capital requirements

If a SREP assessment shows that the arrangements, strategies, processes and mechanisms implemented by the credit institution and the own funds and liquidity held by it do not ensure a sound management and coverage of risks, the ECB may impose a Pillar 2 Requirement (P2R) and a Pillar 2 Guidance (P2G).The ECB sets P2G above the level of binding capital (minimum and additional) requirements and on top of the combined buffers. If a bank does not meet its P2G, this will not result in automatic action by the supervisor and will not trigger any limitations on the distributable amount. However, the ECB will more closely monitor institutions that do not meet their P2G and consider whether, and if so, which, measures are to be taken to address the specific circumstances of the bank.

Banks also need to take into account the systemic buffers (G-SII, O-SII and systemic risk buffers) and the countercyclical buffer that are part of the capital stack.

In order to assess the final measures to be taken, the Supervisory Board will assess every case of a bank not meeting its P2G and may take appropriate bank-specific action as deemed necessary.

As part of the Pillar 2 framework, qualitative outcomes of the stress test are taken into account in the determination of the P2R, especially for the element of risk governance.

When setting P2G, different elements are taken into account as part of a holistic view, for example:

- the starting point for setting the P2G is in general the depletion of capital in the hypothetical adverse scenario (quantitative outcome)[32];

- JSTs take into account the specific risk profile of the individual institution and its sensitivity to the stress scenarios;

- interim changes in the bank’s risk profile since the cut-off date of the stress test and measures taken by the bank to mitigate risk sensitivities, such as relevant sale of assets, are considered.

3.3.3 Supervisory dialogue process[33]

The core objective of the SREP supervisory dialogue process is for the JST to communicate the draft outcomes of the SREP assessment to the institution, explaining the quantitative and qualitative outcomes and expectations that will be included in the SREP decision.

As a key element of the supervisory dialogue, it is recommended that JSTs organise a number of meetings – either physical meetings or conference calls – with the management body of the institution to present the conclusions of the SREP and the measures set out in the draft SREP decision. This allows the institution to understand how it has been assessed and the areas where it needs to improve. The intended effect of this dialogue is to foster robust communication and to allow the institution the opportunity to ask questions and address any uncertainties.

The adoption of a SREP decision follows the standard ECB decision-making process as laid down in the SSM Regulation[34], i.e. complete draft decisions of the Supervisory Board are adopted by the Governing Council through the non-objection procedure.

The SREP decisions must state the reasons on which they are based[35]. Moreover, the opportunity of being heard must be provided before the adoption of the SREP decisions[36] (please see the SSM Supervisory Manual).

4 Element 1: Business model[37]

The assessment of an institution’s business model is split into three parts: i) business model viability, ii) business model sustainability, and iii) business model sustainability over the cycle.

An institution’s course of business can be impaired, and accordingly its ability to generate profits and growth can be adversely affected, not because of a particular risk but due to the sheer nature of the institution’s business model. The risk of such scenarios occurring is called “business model risk”. This outcome may be result from factors within the respective institution (e.g. inefficient design or pricing of key products, inadequate targets, reliance on an unrealistic strategy, excessive risk concentrations, poor funding and capital structures or insufficient execution capabilities) but may well also result from external factors (e.g. a challenging economic environment or a changed competitive landscape).

Business model viability is the ability to generate acceptable returns from a supervisory perspective over the next 12 months. Business model sustainability is a more forward-looking concept that refers to the ability of an institution to generate acceptable returns from a supervisory perspective over a period of three years and through an entire cycle (beyond three years). From a supervisory perspective, it is more important that the returns are achieved by means of an appropriate funding and capital structure and a suitable risk appetite through a full business and economic cycle.

The business model assessment (BMA) is aimed at creating a sound understanding of the functioning of the institution. It provides insights into the key vulnerabilities of an institution on a forward-looking basis. The identification of key vulnerabilities is likely to help identify specific risks to solvency and liquidity that are material to the institution and should, therefore, support the assessment of other SREP elements.

In conducting a BMA, the JST needs to:

- identify the materiality of the business areas (business lines/products or divisions if business line profitability and forecasts are not readily available);

- assess the viability of the institution’s business lines, also compared with its competitors;

- assess the sustainability of those business lines through an entire economic cycle.

The business model assessment is performed in three phases

Table 1 – Business model assessment process

Phase 1 |

Preliminary identification of material business areas, mainly based on information provided by the institution itself (management information, implementing technical standards (ITS), etc.). |

Phase 2 |

Key risk indicators (KRIs). |

Phase 3 |

Supervisory assessment including:

|

Business model risk is assessed only from a quantitative (risk level) perspective.

Phase 1 serves to identify the institution’s business model and the “materiality” of its business areas (business lines/products or divisions, depending on the information available). Information is gathered to provide an up-to-date picture of the institution’s major business areas (business lines, product lines, geographies, etc.). Furthermore, institutions are assigned to peer groups.

Phase 2 assigns the institution an automated score based on profitability indicators. The objective is to assess whether the institution can achieve adequate returns by business line.

Phase 3 analyses the viability and the sustainability of the institution’s business model over the medium term and over-the-cycle. Other indicators are used to better reveal the vulnerabilities of different business models instead of focusing purely on past profitability. The objective is to assess what could happen to the profitability of the business area in an economic downturn, for instance, what the counterbalancing measures could be and whether there is an appropriate balance between business strategy and risk appetite. This phase leads to an overall assessment of the institution’s business model risk that can lead to an adjustment of the Phase 2 score by +2/-1 notches.

5 Element 2: Internal governance and risk management[38]

This section is aimed at analysing risk management and internal governance on a group-wide level. It serves as an overall review of the institution’s operational and organisational structure, overall risk control and risk management framework and the technical architecture supporting the risk management framework and practice. The assessment covers three main aspects:

- the institution’s internal governance framework (including organisational structure, outsourcing, management body, risk management and compliance function and internal audit function);

- its risk appetite framework and risk culture, including remuneration policies;

- its risk infrastructure, data aggregation and reporting.

This element takes a wide perspective with a view to assessing an institution’s overall organisational competence and capacity. This does not include the detailed assessment of the controls for the specific risks to capital and to liquidity and funding, which is conducted for each specific risk category. The risk control framework at the risk category level is expected to be consistent with the firm-wide governance and risk management control framework.

The term “internal governance” refers to the internal organisation of an institution and the way it conducts and manages its business and its risks.

Internal governance, as part of the overall corporate governance, includes the definition of the roles and responsibilities of the relevant persons, functions, bodies and committees within an institution and how they cooperate, both in terms of a governance framework and in terms of actual behaviour. This includes such functions as internal audit, risk management and compliance.

In addition, the internal governance framework encompasses all of the institution’s rules and behavioural standards, including its corporate culture and values, which aim to ensure that the institution or group is properly managed. Among other things, adequate internal governance means setting the institution’s targets, introducing an effective administration and internal control system, establishing sound remuneration policies and practices, identifying and taking on board the interests of all the institution’s stakeholders and going about its business in line with the principles of sound, prudent management, while at the same time abiding by any legal and administrative provisions which may be applicable. If the institution is part of a group, the group dimension also needs to be assessed.

The scope of the assessment of this Element is comprehensive and its objective is to detect any risks deriving from inadequacies in the institutions’ governance, organisation and controls. JSTs take due cognisance of the proportionality principle in assessing the adequacy of the structures and processes in place, taking into account the scale and complexity of the institution.

The internal governance and risk management assessment is performed in three phases:

Table 2 – Internal governance and risk management assessment process

Phase 1 |

Information gathering and preliminary analysis, mainly based on information provided by the institution itself. |

Phase 2 |

Compliance check of relevant CRD articles relating to internal governance and risk management. |

Phase 3 |

Supervisory assessment including, but not limited to[39]:

|

Internal governance and risk management is assessed only from a qualitative (risk control) perspective.

Phase 1 relies on various information sources such as:

- internal documentation outlining features related to, for example i) the management body in its supervisory and its management functions; ii) sub-committees (charter, role, composition, succession planning and the skills and experience of their members, relevant minutes on selected topics, etc.); iii) the risk appetite framework; and iv) remuneration policies, etc.;

- the organisational structure (organisational chart identifying key functions and committees); reporting lines and allocation of responsibilities, including key function holders and information on their knowledge, skills and experience, absence of conflicts of interest, and reputation; relevant internal policies laying down governance-related processes and organisational arrangements, including those related to the internal control functions (such as internal audit/risk management/compliance policies, charter, plans and findings reports, etc.).

Phase 2 encompasses a limited list of questions rooted in regulatory references relating to internal governance and risk management arrangements.

Phase 3 aims to check whether the internal governance framework works in practice and allows the institution to comply with regulatory requirements. It is carried out from a holistic, group-wide perspective.

6 Element 3: Risks to capital[40]

The determination by the JST of the capital needed by the institution to cover its capital-related risks relies on three “building blocks”. This makes it possible to analyse the institution’s capital position from three different and complementary angles. The assessment of each block is broken down into precise steps, which allow the JST to exercise judgement based on its knowledge of the institution.

6.1 Block 1: Assessment of risks to capital

In Block 1, an assessment of the risk levels and risk controls is carried out by the JST for the four capital-related risks: credit risk, market risk, operational risk, and interest rate risk in the banking book. For each of these risks, risk levels and risk controls are assessed in three complementary phases: i) a data/information gathering phase (Phase 1); ii) a scoring phase (Phase 2) based on pre-defined indicators (risk level) or compliance checks (risk controls); and iii) a supervisory assessment phase (Phase 3). Scores calculated in Phase 2 can be adjusted by the JST in Phase 3 to a certain extent (+2/-1 notches, i.e. reduced by a maximum of two notches or improved by a maximum of one notch), in line with the constrained judgement. Phase 3 assessments must be justified and documented and are subject to horizontal consistency checks.

Block 1: an assessment of risks to capital in three phases

For each risk category, the risk level and risk control assessments performed in Phase 3 are combined into a combined rationale and a combined score. Then the assessments of individual risk categories are subsequently combined into an overall capital-related risk assessment.

6.1.1 Block 1: Credit risk

Credit risk is defined as the possibility that an institution suffers losses stemming from an obligor’s failure to repay a loan or otherwise meet a contractual obligation in accordance with agreed terms.

For most institutions, loans are the largest and most obvious source of credit risk. However, other sources of credit risk may also arise from other activities, be they booked in the banking book or in the trading book, on or off-balance-sheet. For instance, institutions face credit risk or counterparty risk through various financial instruments, including acceptances, interbank transactions, trade financing, foreign exchange transactions, forward contracts, swaps, bonds, equities, options, the extension of commitments and guarantees, and the settlement of transactions.

There are some risks (e.g. counterparty risk, risk from securitisation positions, etc.) which, because of their nature, could fall under the scope of both credit and market risk. However, these risks have been included in the broad credit risk category following the regulatory risk framework. Nevertheless, they could also be included in the market risk category if it were considered more appropriate in view of an institution’s business model and the relevance of its risks.

The typical dimensions to be considered when reviewing an institution’s credit risk are the following:

- the size of credit exposures/activities;

- the nature and composition of the credit portfolio, including its concentration;

- the evolution of the credit portfolio;

- the quality of the credit portfolio;

- the credit risk parameters, including internal ratings-based ones (e.g. probability of default, loss given default, credit conversion factors) and other internally estimated parameters;

- credit risk mitigates and coverage.

External factors, such as the economic environment and market developments, also need to be considered.

6.1.2 Block 1: Market risk

Market risk is defined as the risk of losses in on and off-balance-sheet positions arising from movements in market prices with impacts on profit and loss or on the capital position of the institution. It covers the risk arising from:

- risk factors underlying the instruments held: interest rate risk (excluding positions in the banking book), equity risk, credit spread risk, foreign exchange risk (including the gold position) and commodity risk (including the precious metal position);

- features of the positions taken: valuation risk related to complex and illiquid positions, non-linear risk and gap risk;

- the relationship with the counterparty to the transactions: credit valuation adjustment risk and settlement risk;

- risk management practices of the institution: hedging strategies, basis risk and concentration risk.

6.1.3 Block 1: Interest rate risk in the banking book

Interest rate risk is an institution’s exposure to unfavourable movements in interest rates. IRRBB includes the interest rate risk that arises from potential changes in interest rates that adversely affect an institution’s non-trading activities.

The IRRBB assessment comprises two complementary analyses:

- analysis from an economic value perspective, which focuses on how changes in interest rates affect the present value of the expected net cash flows;

- analysis from an earnings perspective, which focuses on the impact of changes in interest rates on near-term earnings.

Institutions should demonstrate their capacity to identify and assess the different components of IRRBB: i) gap risk, ii) basis risk and iii) option risk, which can be defined as follows.

- Gap risk is the risk related to timing mismatches in the maturity (for fixed rate) and repricing (for floating rate) of assets, liabilities and off-balance sheet short and long-term positions, or from changes in the slope and the shape of the yield curve.

- Basis risk is the risk arising from hedging exposures to one interest rate with exposures to a rate that reprices under slightly different conditions.

- Option risk (or optionality) is the risk arising from options where the institution or its customer can alter the level and timing of their cash flows, including embedded options, e.g. consumers redeeming fixed-rate products when market rates change. This optionality can either be automatic, i.e. the holder will almost certainly exercise the option if it is in the holder’s financial interest to do so, or behavioural, i.e. the decision to exercise depends not only on interest rates but also on client behaviour, which is often expected to change as interest rates change.

6.1.4 Block 1: Operational risk

Operational risk is defined as the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events.

This definition includes legal risk, compliance risk, conduct risk, model risk of models not relating to other SREP risk categories, and information technology (IT or ICT) risk but excludes strategic and reputational risk. Nevertheless, reputational risk should be assessed together with operational risk owing to the strong connection. Operational risk is further classified into seven event types:

- internal fraud;

- external fraud;

- employment practices and workplace safety;

- clients, products and business practices;

- damage to physical assets;

- business disruption and system failures;

- execution, delivery and process management.

6.2 Block 2: Challenging an institution’s internal assessment of its capital needs

In Block 2, the JST assesses the institution’s internal processes to identify and estimate the capital necessary to cover its own risks (internal capital adequacy assessment process (ICAAP)). This assessment is performed from both a qualitative perspective and a quantitative perspective. The objective is to assess whether the institution’s ICAAP framework is reliable and proportionate to the nature, scale and complexity of the institution’s activities, checking for instance how the institution identifies, measures and aggregates its risks; how the ICAAP is embedded into its daily management process, including the role of the management body as well as the roles of internal control, validation and audit as part of the governance framework of ICAAP; how the ICAAP affects the capital planning and also how the forward-looking perspective is considered. The ICAAP assessment should also inform the internal governance and risk management assessment. In addition, the review of both the qualitative and quantitative aspects of the ICAAP plays a significant role in the determination of the additional capital requirements by the supervisor.

For further details, please refer to the ECB Guide to the internal capital adequacy assessment process (ICAAP), published in November 2018.

6.3 Block 3: Challenging an institution’s internal capital stressed estimates

In Block 3, the JST assesses the institution’s capacity to cover its capital needs from a forward-looking perspective, assuming stressed economic and financial developments. This is done using a wide range of information sources, including the institution’s internal stressed projections, SSM’s stressed supervisory calculations, and the outcome of supervisory (bottom-up and/or top-down) stress tests when available.

Institutions usually rely on a wide range of internal stress tests and sensitivity analyses to determine their capital trajectory and their ability to raise own funds at a certain horizon. This helps them to identify backstop actions that may be warranted at an early stage should adverse scenarios materialise. An institution’s ICAAP risk taxonomy is expected to be the same overall in normal and in stressed conditions, even if in the latter case additional risks may be identified that are not relevant in normal conditions.

To review these stress tests, the ECB follows the principles and recommendations established in this respect by international supervisory bodies and in the ECB Guide to the internal capital adequacy assessment process (ICAAP), published in November 2018.

6.4 Capital adequacy assessment

The assessment of an institution’s capital adequacy aims to evaluate its capacity to comply with its Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 capital requirements both point in time and at a certain horizon, in normal and stressed conditions. After the JST has assessed the three blocks, it has obtained a view on the institution’s capital needs from three complementary angles.

As far as the quantity of capital held by the institution is concerned, the JST contrasts the amount of own funds with the level of its regulatory capital requirements: minimum capital, Pillar 1 ratio, additional capital requirements (explained in the SREP decision section), leverage ratio.

7 Element 4: Risks to liquidity[41]

As for capital-related risks, the determination by the JST of the liquidity adequacy of the institution to cover its liquidity and funding-related risks relies on three “building blocks”. This makes it possible to analyse the institution’s liquidity and funding position from three different and complementary angles. The assessment of each block is broken down into precise steps, which allow the JST to exercise judgement based on its knowledge of the institution.

7.1 Block 1: Assessment of risks to liquidity

In Block 1, the JST assesses the risk levels and risk controls for short-term liquidity risk and funding sustainability risk in three complementary phases.

Liquidity is the ability of an institution to fund increases in assets and meet obligations as they come due, without incurring unacceptable losses. The fundamental role of credit institutions in the maturity transformation of short-term deposits into long-term loans makes them inherently vulnerable to liquidity risk, this latter i) being of an institution-specific nature and ii) affecting markets as a whole. Effective liquidity risk management helps ensure an institution’s ability to meet cash flow obligations, which are uncertain as they are affected by external events and other agents’ behaviour.

Short-term liquidity risk and funding sustainability risk level scores are combined at the end of the process into a single liquidity risk level score.

The risk control assessment is performed together for short-term liquidity risk and funding sustainability risk and one combined risk control score is assigned.

The final outcome is summarised in an overall Block 1 liquidity risk rationale and score. It reflects the dynamic nature of short-term liquidity and funding risks, which can materialise very rapidly and therefore need to be assessed at a relatively granular level depending on the overall risk appetite.

7.1.1 Block 1: Short-term liquidity risk

Short-term liquidity risk is the risk that an institution is unable to meet its short-term financial obligations when they fall due. Obligations can be payment obligations (to deliver cash) or obligations to deliver collateral (assets). The risk generally arises when an institution faces outflows that exceed its inflows and is not able to generate enough liquidity with its counterbalancing capacity over a horizon of up to one year. Therefore, potential maturity mismatches in cash and collateral flows across regions, currencies and netting arrangements need to be assessed.

An institution’s short-term liquidity risk is divided into two dimensions:

- its cash and collateral needs arising from contractual and behavioural cash payment and collateral delivery obligations;

- its available counterbalancing capacity.

Both need to be assessed based on point in time, at a certain horizon, and through the cycle. The forward-looking view needs to be taken assuming both normal and stressed economic conditions.

7.1.2 Block 1: Funding sustainability risk

Funding sustainability risk is the risk that an institution is unable to fund its balance sheet mid to long-term in a sustainable way. This includes the capacity to roll over maturing funding and increase liabilities at any time to cover refinancing needs. Factors such as a poor capital position, an unclear business strategy, a negative rating outlook or a negative investor opinion can restrict access to funding markets and thereby increase the risk.

A balanced funding profile will to a certain extent shield an institution from market disruptions. Institutions must therefore strive to maintain the right balance between short-term and long-term, secured and unsecured funding, and their different funding sources (in terms of counterparties, instruments, costs, currencies and markets). A weakness in one area (e.g. a high concentration in certain funding segments, excessive maturity mismatches or high levels of asset encumbrance) can exacerbate an already stressed situation in terms of cumulative liquidity and refinancing requirements.

An institution’s funding sustainability risk is divided into two dimensions:

- its medium-to-long-term funding needs;

- its capacity to raise the necessary funding over time.

Both need to be assessed based on point in time, at a certain horizon, and through the cycle. The forward-looking view needs to be taken assuming both normal and stressed economic and financial market conditions.

7.2 Block 2: Challenging an institution’s internal assessment of its liquidity needs

In Block 2, the JST assesses the institution’s internal processes to identify and estimate the liquidity necessary to cover its own risks (internal liquidity adequacy assessment process (ILAAP)). This assessment is performed from both a qualitative perspective and a quantitative perspective. The objective is to assess whether the institution’s ILAAP framework is reliable, checking for instance how it identifies its risks, how ILAAP is embedded into its daily management process (e.g. the roles of internal control, validation and audit are as part of the governance framework of ILAAP), how the quantification models are constructed, controlled, and acted upon, etc. It also has a forward-looking perspective. The ILAAP assessment should inform internal governance and risk management assessment. The outcome of Block 2 assessment should be taken into account when assigning the overall liquidity adequacy score and when considering imposition of liquidity measures.

For further details, please refer to the ECB Guide to the internal liquidity adequacy assessment process (ILAAP), published in November 2018.

7.3 Block 3: Challenging an institution’s internal liquidity stressed estimates

In Block 3, the JST assesses the institution’s capacity to cover its liquidity needs from a forward-looking perspective, assuming stressed economic and financial developments. After finalising the assessment the JSTs should consider if there is a need to impose liquidity measures on a credit institution. SREP measures should reflect weaknesses and vulnerabilities identified in the liquidity risk assessment, which can be either qualitative or quantitative in nature (or both).

Liquidity stress tests play a key role in the quantitative assessment of institutions’ liquidity needs and their ability to continue their operations through periods of stress. For one thing, liquidity stress tests serve to challenge the internal stress tests that are developed by the institutions themselves. For another, together with the internal stress tests of the institutions, they help identify the inherent liquidity and funding risks faced by the institution in a forward-looking manner. The liquidity stress test framework takes on a top-down approach leveraging on supervisory data reporting.

7.4 Liquidity adequacy assessment

The liquidity adequacy assessment combines the conclusion from Blocks 1, 2 and 3 into a score. The JST’s assessment is formalised in a rationale and a score. There is no mechanical rule to follow when assigning the score. Rather, the different characteristics presented in score definitions are to be considered as typical for the scores they are associated with. JSTs should judge all elements assessed under this category from a holistic perspective and assign the score that overall reflects the liquidity adequacy situation the best.

Quantitative measures should in particular be considered when there are material risks that are not covered by the LCR and the institution is not adequately mitigating these risks via its ILAAP.

- Council Regulation (EU) No 1024/2013 of 15 October 2013 conferring specific tasks on the European Central Bank concerning policies relating to the prudential supervision of credit institutions (OJ L 287, 29.10.2013, p. 63).

- Regulation (EU) No 468/2014 of the European Central Bank of 16 April 2014 establishing the framework for cooperation within the Single Supervisory Mechanism between the European Central Bank and national competent authorities and with national designated authorities (SSM Framework Regulation) (ECB/2014/17) (OJ L 141, 14.5.2014, p. 1).

- EBA Guidelines on common procedures and methodologies for the supervisory review and evaluation process (SREP) and supervisory stress testing (EBA/GL/2014/13), referred to in this report as the “EBA Guidelines on SREP”.

- Directive 2013/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on access to the activity of credit institutions and the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms, amending Directive 2002/87/EC and repealing Directives 2006/48/EC and 2006/49/EC (OJ L 176, 27.6.2013, p. 338).

- Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms and amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 (OJ L 176, 27.6.2013, p. 1).

- According to the EBA Guidelines on SREP, “Overall SREP assessment” means the up-to-date assessment of the overall viability of an institution based on assessment of the SREP elements.

- Article 104 of the CRD IV and Article 16 of the SSM Regulation.

- Article 97-99 of the CRD IV.

- Title 4 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Title 5 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Title 6-7 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Title 8-9 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- The EBA Guidelines on SREP define the TSCR as “the sum of own funds requirements as specified in Article 92 of Regulation EU 575/2013 and additional own funds requirements determined in accordance with the criteria specified in this Manual”.

- “Considerations in relation to inherent risk”, in line with the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- “Considerations in relation to adequate management and controls”, in line with the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Title 2 (Section 2.1.4) and Title 10 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Paragraph 33 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Paragraph 151 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Source: EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- “Considerations in relation to inherent risk”, in line with the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- “Considerations in relation to adequate management and controls”, in line with the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Capital adequacy is the only exception. That category consists only of phases 1 and 3.

- Title 2 (Section 2.2.1) of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- “Considerations in relation to inherent risk”, in line with the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Title 2 (Section 2.2.1) of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- “Considerations in relation to adequate management and controls”, in line with the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Title 2 (Section 2.2.3) of the EBA Guidelines on SREP, reference to “Supervisory view”.

- Title 2 (Section 2.1.4) and Title 10 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Paragraph 31 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Please refer to the SSM Supervisory Manual and Title 2 (Section 2.1.5) of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Title 7 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Paragraph 387 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Title 2 (Section 2.1.5) of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Article 26(8) of the SSM Regulation.

- Article 22(2) of the SSM Regulation and Article 33 of the SSM Framework Regulation.

- Article 22(1) of the SSM Regulation and Article 31 of the SSM Framework Regulation.

- Title 4 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Title 5 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- As part of SREP, JSTs carry out an assessment of the sub-categories of internal governance and institution-wide controls as defined in Paragraph 89 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Title 6-7 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.

- Title 8-9 of the EBA Guidelines on SREP.