- SPEECH

Introductory statement

Introductory statement by Andrea Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the press conference on the results of the 2020 SREP cycle

Frankfurt am Main, 28 January 2021

Jump to the transcript of the questions and answersWelcome to our press conference on the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process – SREP for short.

This year’s press conference will naturally be rather different, due to the unprecedented events that have been affecting all of our lives since the beginning of last year. In 2020, the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic was the event that had the greatest impact on the real economy and the resilience of European banks. In my remarks today, I will briefly cover four topics.

First, the extraordinary features of this crisis.

Second, the resilience of the euro area banking sector in 2020.

Third, the major vulnerabilities we have identified through our monitoring and our pragmatic SREP.

And fourth, our supervisory priorities and the outlook for the euro area banking sector going into 2021.

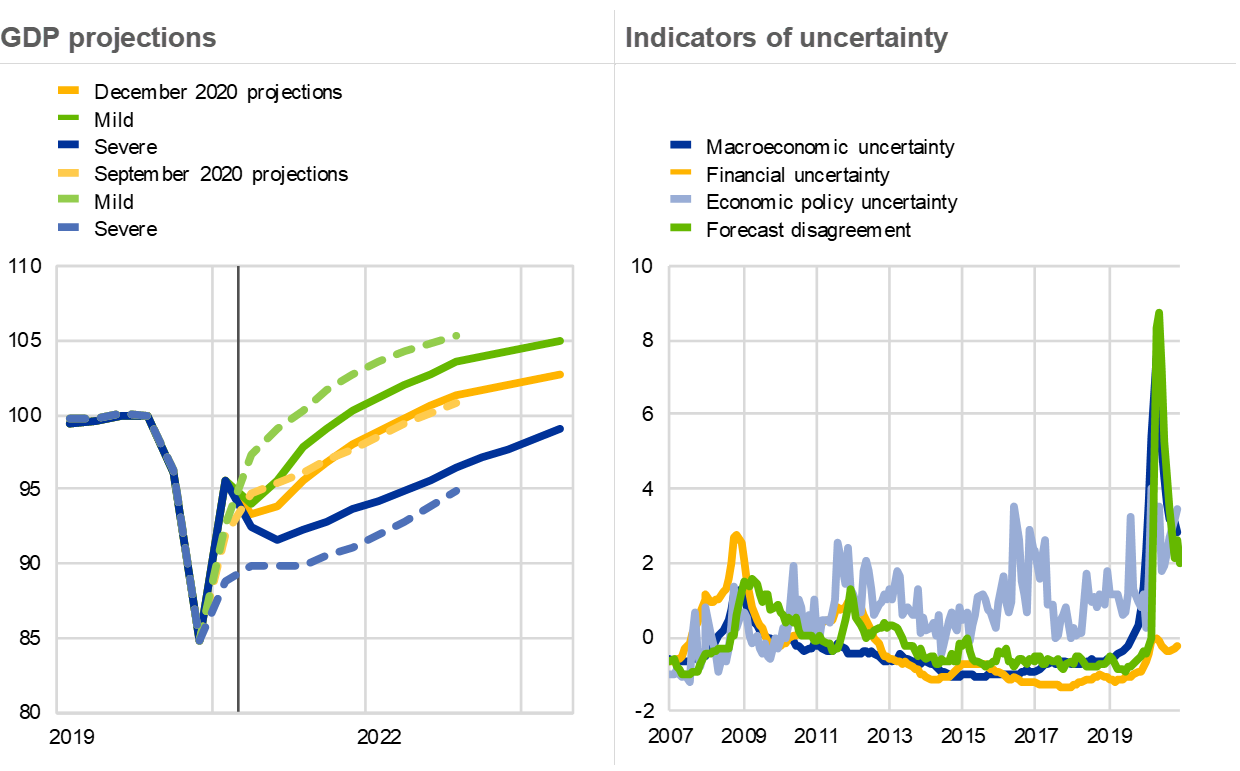

The extraordinary features of the COVID-19 shock

Uncertainty has been the defining feature of this unprecedented shock. In the initial phase of the pandemic, macroeconomic uncertainty reached levels never before recorded, with lightning fast implementation of social restrictions and economic support policies, and plummeting levels of business and consumer confidence. This left all economic agents, including banks, virtually unable to make projections one or two years into the future. Uncertainty abated somewhat in the course of 2020, as shown by the higher degree of similarity across the ECB’s projection scenarios in December compared with that seen in September. Still, under the baseline scenario of the December projections, GDP will drop by more than 7% in 2020 and the economy will only return to pre-crisis levels by mid-2022. If the severe scenario were to materialise, this economic rebound would be delayed until 2023.

Chart 1

Covid-19 caused an extraordinary economic shock and created significant uncertainty…

Source left-hand chart: December 2020 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections.

Note left-hand chart: The vertical line marks the start of the projection horizon.

Source right-hand chart: Economic Bulletin, Issue 6, ECB, 2020.

Notes right-hand chart: All measures of uncertainty are standardised to mean zero and unit standard deviation over the full horizon starting in June 1991. A value of 2 should be read as meaning that the uncertainty measure exceeds its historical average level by two standard deviations. The latest observations are for August 2020.

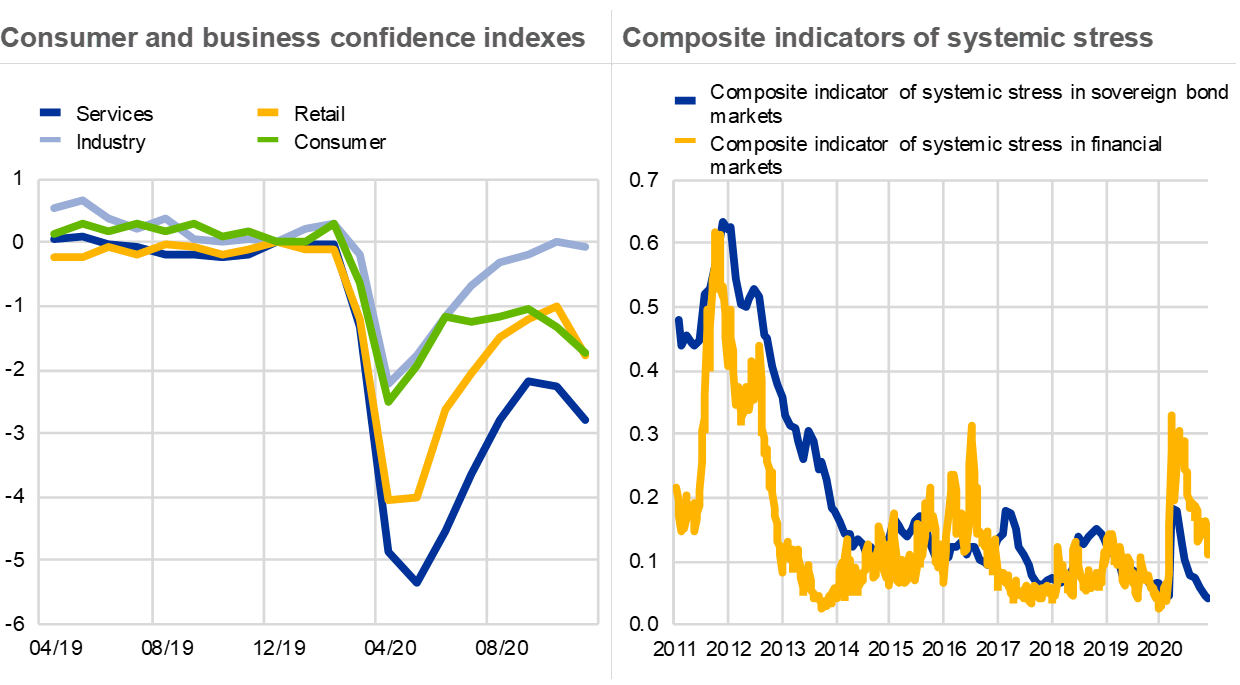

Financial markets have been distressed, although less so than during the great financial crisis and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis. Unlike those crises, however, the pandemic crisis is not a phenomenon generated by financial or banking markets. Many have pointed out that this time, banks are not part of the problem – but there was a palpable risk they could aggravate the problem, as the combined impact of spiking uncertainty, falling confidence and increasing risk aversion threatened to trigger a deeply procyclical reaction in the banking sector. In order to make banks part of the solution, a wide range of public policy measures were adopted to motivate adjustments in behaviour.

Chart 2

…along with falling confidence and some distress in financial markets.

Source left-hand chart: Financial Stability Review, ECB, November 2020.

Source right-hand chart: Financial Stability Review, ECB, May 2020.

When the pandemic shock first hit, businesses, companies, banks and other organisations scrambled to reprioritise their activities to safeguard health while attempting to minimise disruptions. Lockdown measures imposed across Europe forced the banking industry, as well as other businesses, to implement remote working measures. In March and April in particular, banks focused on implementing operational contingency plans and creating capacity to continue to serve their markets and customers. Given these exceptional circumstances, ECB Banking Supervision adopted a pragmatic approach when undertaking its annual core activity – the SREP – also in line with the European Banking Authority (EBA) guidelines.

Figure 1

An extraordinary year demanded a “pragmatic” SREP, with re-prioritisation of supervisory activities and processes

During the 2020 SREP cycle, we focused on how banks are handling the challenges and risks to capital and liquidity arising from the ongoing crisis. We decided to keep the Pillar 2 requirements (P2R) stable, except where individual banks were affected by exceptional circumstances which justified changes. The Pillar 2 guidance (P2G) has remained stable as well, reflecting the postponement of the EBA stress test exercise. Moreover, we have not updated banks’ SREP scores unless justified by exceptional circumstances affecting individual banks. We mainly communicated our supervisory concerns to banks through qualitative recommendations, and we took a targeted approach to collecting information on both the internal capital adequacy assessment process (ICAAP) and the internal liquidity adequacy assessment process (ILAAP).

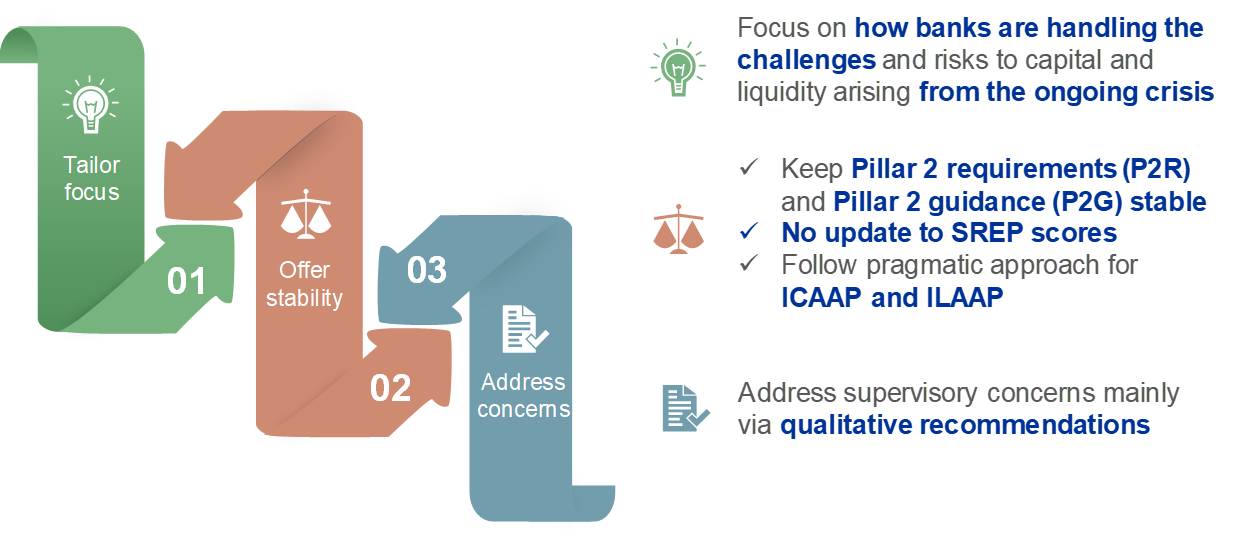

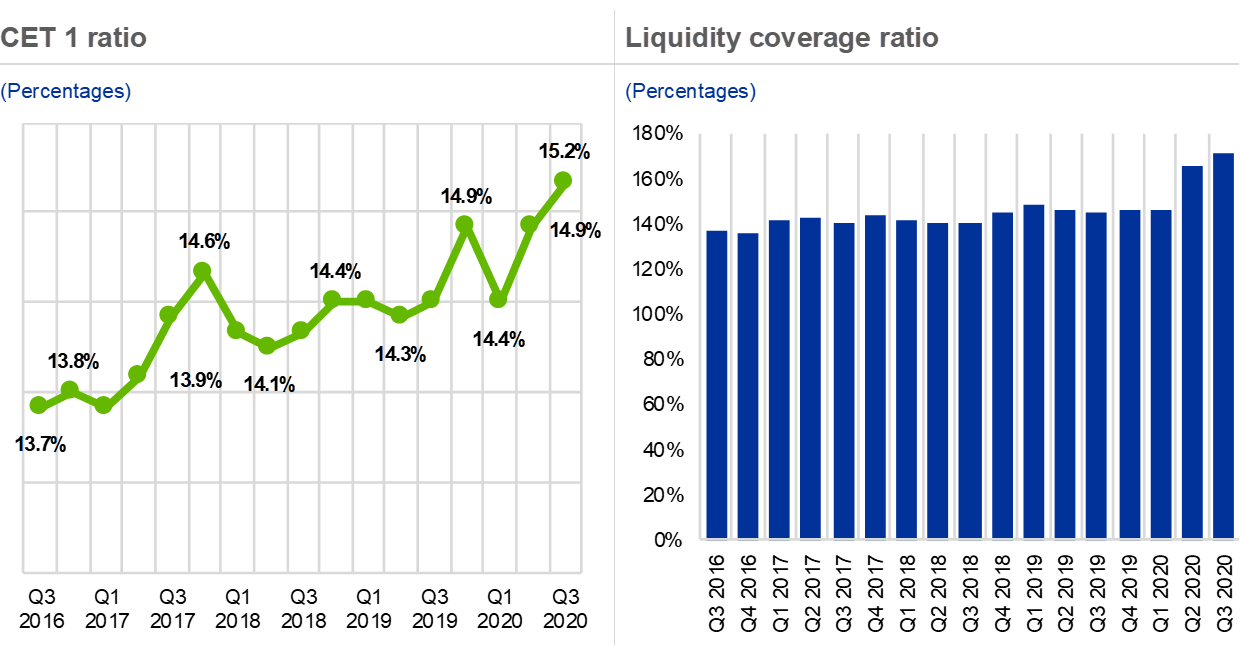

The euro area banking sector was resilient in 2020

European banks were in much better prudential shape when the pandemic shock hit than they were going into the great financial crisis. This can be attributed to both the regulatory overhaul put in place by the international community following the last crisis and the achievements of the first six years of single supervision within the banking union. For the fourth quarter of 2019, banks reported a Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital ratio of 14.9%.

Chart 3

Banks entered the crisis well capitalised and with ample liquid assets…

Source left-hand chart: Supervisory reporting.

Note left-hand chart: Sample comprises 110 SIs as of Q3 2020.

Source right-hand chart: Supervisory reporting.

Notes right-hand chart: Sample comprises 110 SIs as of Q3 2020.

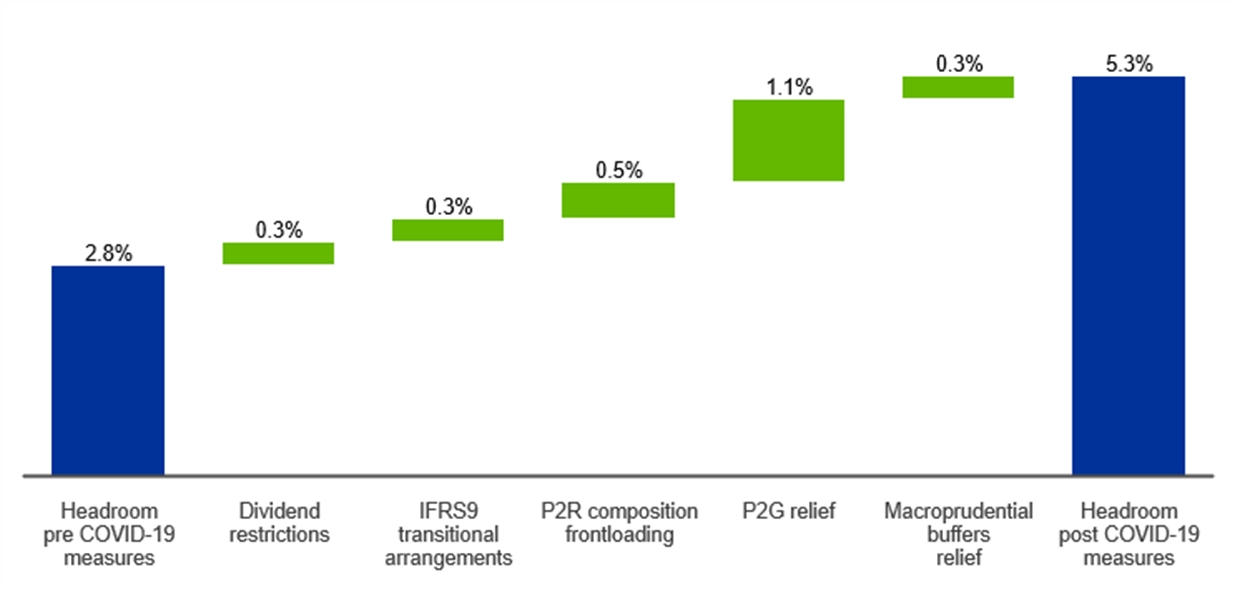

In order to counter the economic fallout of the COVID-19 shock, national governments and EU authorities deployed measures of unprecedented nature and magnitude to support banks and the economy, including large and coordinated fiscal and monetary expansion as well as loan moratoria and public loan guarantees. As microprudential supervisors, we encouraged banks to adopt transitional IFRS 9 requirements to smooth the impact of provisions on regulatory capital, we brought forward the 2021 requirements under the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD V) on the composition of P2R, which are less demanding in terms of CET1 capital, and we declared that banks could temporarily operate below the level of P2G until at least the end of 2022 and, where needed, even below the capital conservation buffer (CCB). Several macroprudential authorities also lowered or suspended the buffer requirements in their remit. Taken together, and excluding the flexibility on the CCB, these measures almost doubled banks’ capital headroom, from 2.8% to 5.3% as of the third quarter of 2020. Our estimates of the policy-induced headroom remain a lower bound, as we cannot quantify additional regulatory relief, such as the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) quick fix, which lowered risk-weighted assets (RWAs) and hence further increased headroom. Such a unified and prompt supervisory response would have been unthinkable before the banking union and European banking supervision were set up, when supervision was segmented across national lines.

Chart 4

… and were granted further relief to cope with the extraordinary shock.

Capital headroom as of Q3-2020

(percentage points CET1 ratio)

Source: Supervisory reporting for Q4 2019 and Q3 2020; IFRS 9 transitional arrangements and dividend distributions: ECB estimates; Pillar 2 requirements and Pillar 2 guidance pre and post COVID-19 relief measures: 2019 SREP decisions applicable in 2020.

Note: Sample comprises 112 SIs.

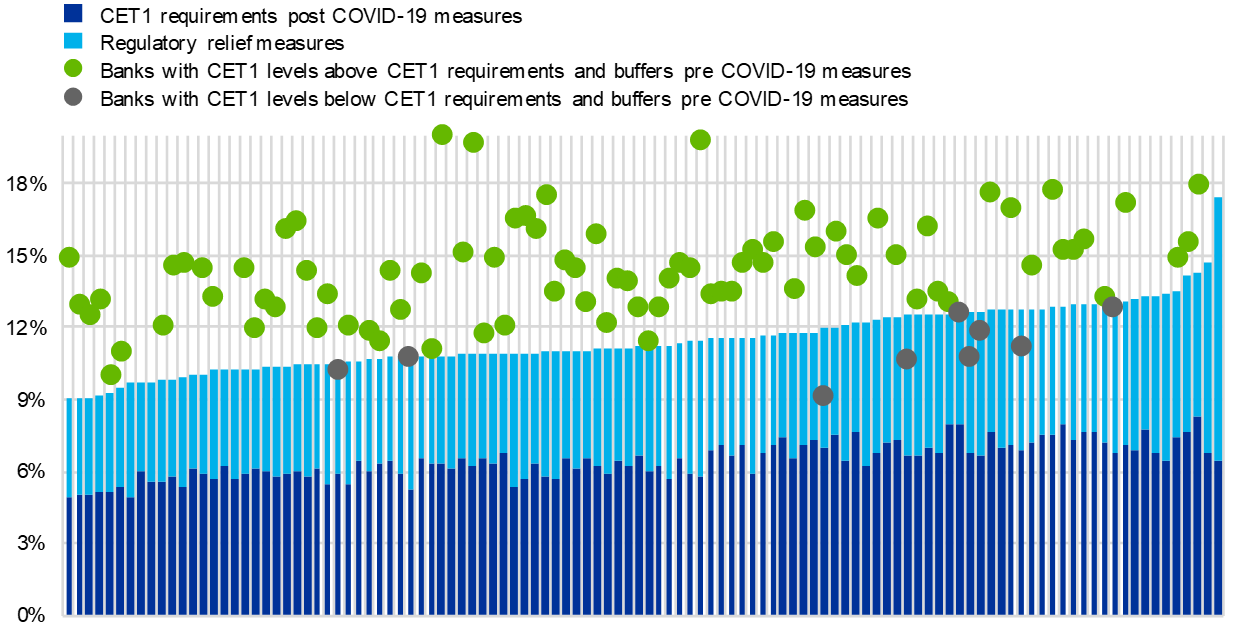

Going into 2021, ample room for loss absorption is available to all banks under our supervision, especially considering that the buffer flexibility we have granted includes the CCB and remains valid until at least the end of 2022. Since the third quarter of 2020, banks under our supervision have been well capitalised. Only a few banks have dipped into their buffers so far. As credit losses from the pandemic are yet to materialise, this is likely to be a consequence of idiosyncratic and structural issues rather than of the COVID-19 downfall. I will come back to this point in a moment.

Chart 5

Most banks are capitalised above requirements and guidance, with ample relief available to absorb future losses.

(Percentages)

Source: SREP 2020 values (P2R and P2G) based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021.

Note: CET1 levels, systemic buffers (G-SII, O-SII and systemic risk buffer) and countercyclical capital buffer as of Q3 2020. CET1 levels, after covering post COVID-19 shortfalls in Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 requirements with additional Tier 1 and Tier 2 instruments. Regulatory relief measures are intended to be: Pillar 2 guidance, capital conservation buffer, relief of systemic buffers (G-SII, O-SII and systemic risk buffer) and countercyclical capital buffer made available by national authorities, Pillar 2 composition in AT1 and T2, following the ECB decision on 12 March 2020 to frontload the Capital Requirements Directive V (CRD V), for which the P2R should have the same capital composition as that of Pillar 1. Therefore, P2R should be held with 56.25% in CET1 and 75% in Tier 1 as a minimum requirement. Sample comprises 112 SIs.

It would be premature, in my opinion, to see the fact that banks have not freely used the buffers as an indictment of the Basel framework’s effectiveness in this regard. Some observers have already called for sweeping reform in this area. Personally, I believe that nothing conclusive can be said until the pandemic-induced losses start materialising. Once this happens, and where necessary, I would encourage banks to make use of all loss absorption room made available to them and not to refrain from implementing an early and accurate risk management strategy due to capital concerns.

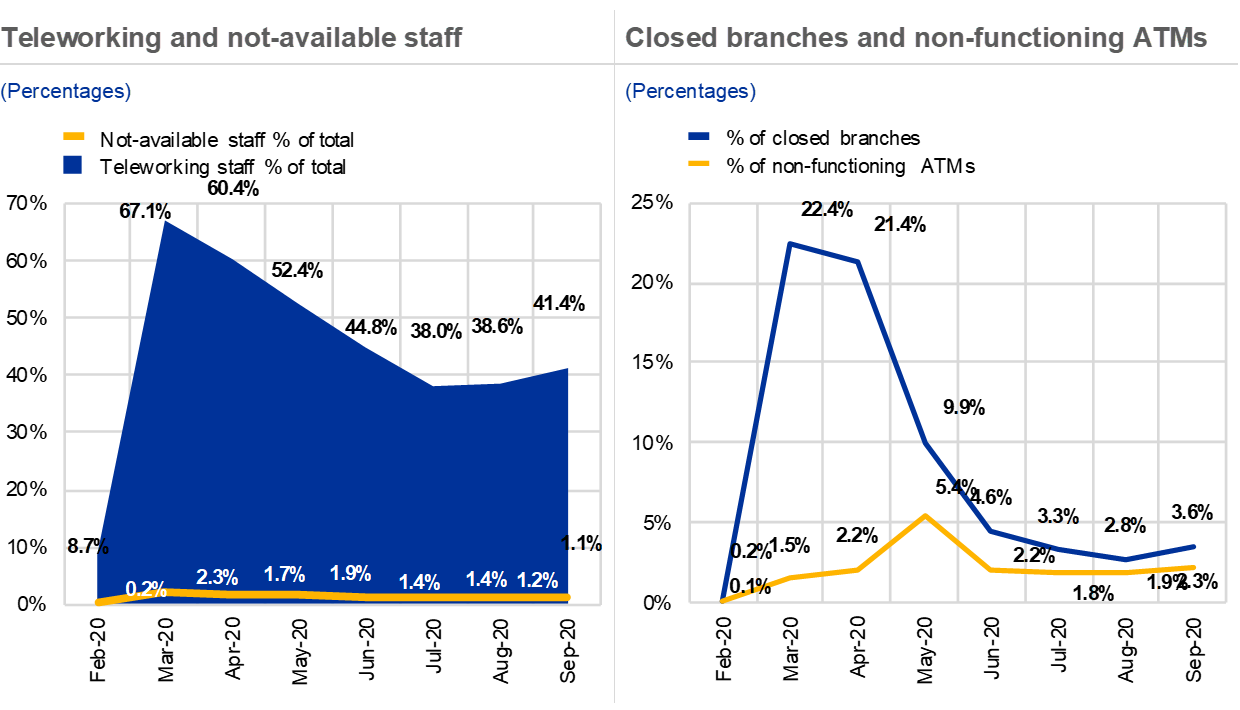

Thanks to the COVID-19 ad hoc reporting introduced by the EBA, we were able to monitor the operational performance of the banks we supervise on a monthly basis. We set up a COVID-19 monitoring task force, drawing on expertise from all corners of our organisation, to work together to quickly identify points of stress. This gave us access to real-time information about the effects of the pandemic on the banking sector and enabled us to optimally prepare ourselves to address concerns.

Our staff were subject to the same constraints as many people across Europe as we had to implement wide-ranging teleworking arrangements. This did not impair our ability to conduct effective supervision: collaboration across our teams was enhanced, with daily alignment meetings instituted among our top management team; our Joint Supervisory Teams (JSTs) increased surveillance touchpoints with the banks they supervise; and the flows of information across the monetary policy and supervisory sides of the ECB were intensified. Our new ways of working proved extremely effective in delivering the necessary information and data analysis, and our information gathering demonstrated that banks were able to ensure business continuity despite lockdowns, with limited disruptions. The situation also highlighted opportunities for cost savings across the sector, as banks showed that they could continue to operate despite temporary branch closures.

Chart 6

Banks were able to ensure continuity of business despite lockdowns, with limited disruptions.

Source left-hand chart: COVID-19 supervisory reporting as of Q3 2020.

Source right-hand chart: COVID-19 supervisory reporting as of Q3 2020.

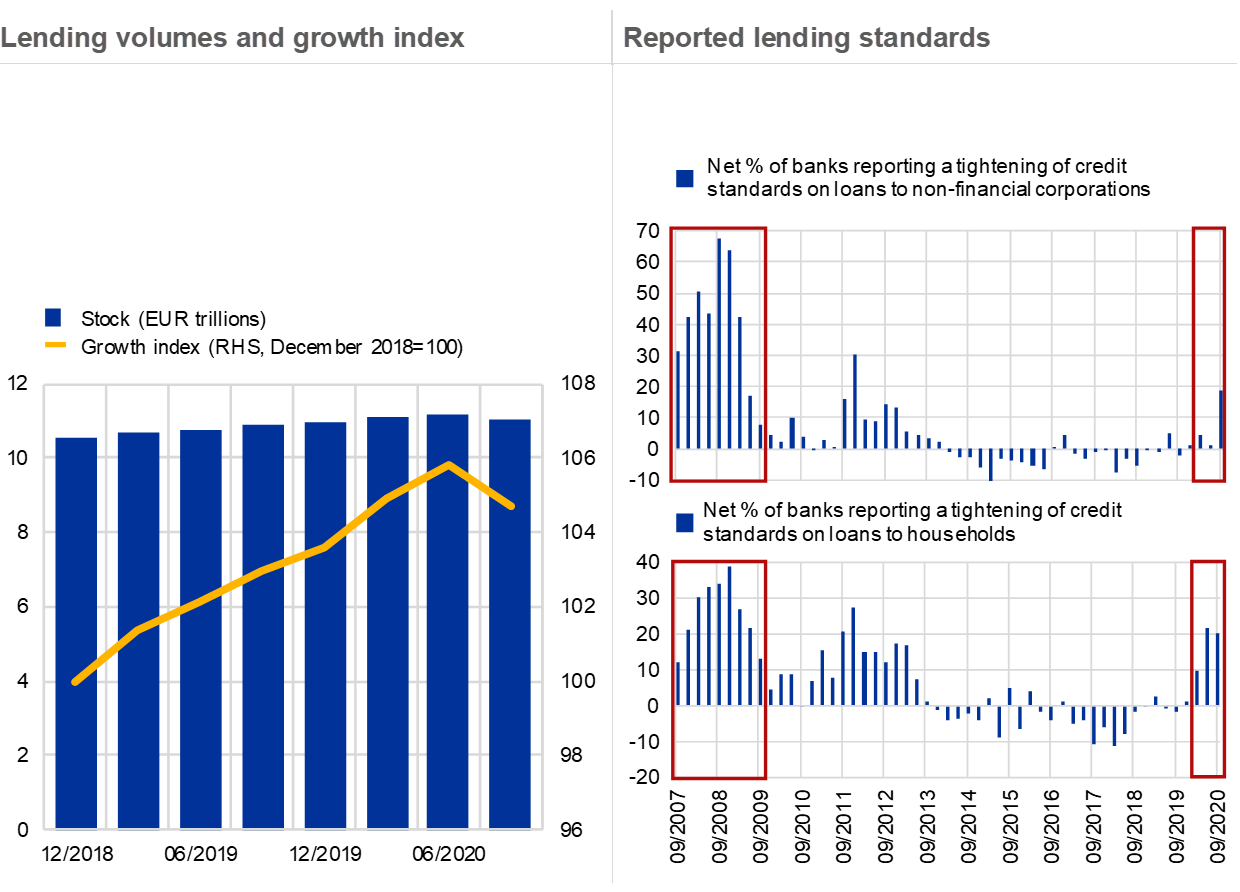

But what matters most is that we have so far averted excessive procyclicality. Lending to firms and households continued to grow in 2020, even though we saw a slowdown in the third quarter. And compared with what happened during the great financial crisis, last year banks reported a much more moderate tightening of credit standards.

Chart 7

Excessive procyclicality from the shock averted so far.

Source left-hand chart: Supervisory reporting as of Q3 2020 and ECB calculations.

Note left-hand chart: Sample comprises 104 SIs.

Source right-hand chart: Euro area bank lending survey.

Notes right-hand chart: A positive net percentage indicates that a larger proportion of banks have tightened credit standards (“net tightening”), whereas a negative net percentage indicates that a larger proportion of banks have eased credit standards (“net easing”).

If we dig a bit deeper into the lending data, the trend reversal in the third quarter of 2020 seems to be accounted for by the business euro area banking groups conduct outside the euro area. This is evidence of a slight international retrenchment in lending which, unsurprisingly, is often a characteristic of recessionary shocks. In this specific case, the asymmetry in lending developments inside and outside the banking union may also be explained by the levels of public support deployed within the euro area, especially in the form of loan guarantees.

Vulnerabilities identified by our monitoring and the pragmatic SREP

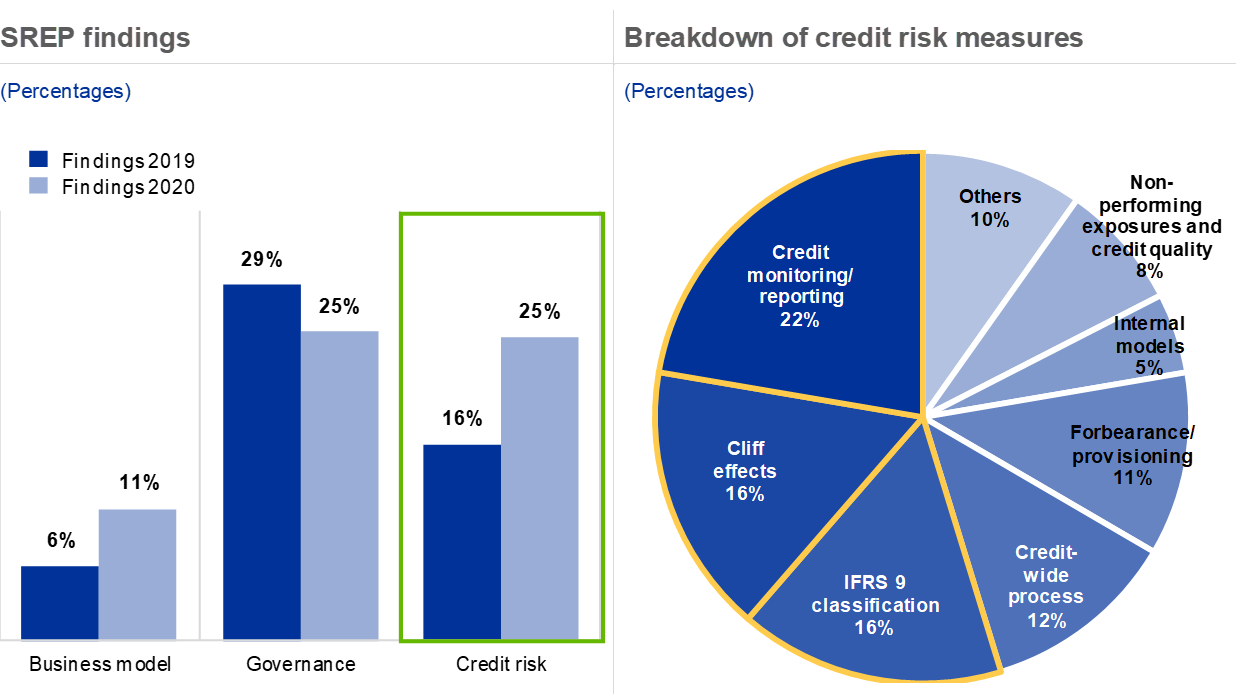

Our monitoring and the pragmatic SREP identified credit risk, profitability and internal governance as the main areas of supervisory concern. Many governance findings from last year are still outstanding. Almost all significant banks (80%) were addressed with credit risk recommendations; the number of findings concerning credit risk increased by 79%. The number of findings concerning business models rose even more strongly, by 105%.

Chart 8

Credit risk, profitability and internal governance are the predominant areas of supervisory concern.

Note left-hand chart: In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, on 27 March 2020 the qualitative measures were formally replaced by qualitative recommendations in order to address supervisory concerns, unless justified by exceptional circumstances affecting an individual institution. Moreover, 2019 qualitative measures are considered outstanding mainly due to the ECB decision to extend the deadline for complying with the SREP 2019 qualitative measures by six months. Qualitative recommendations were addressed to all SREP SIs in 2020 as a result of the JST findings (by comparison, qualitative measures were applied to 83% of SIs in 2019). Sample: SREP 2020 values based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021. SREP 2019 values based on 109 SREP 2019 decisions finalised as at 31 December 2019 and applicable from 1 January 2020.

Notes right-hand chart: Credit-wide processes refer to a wide range of issues related to credit risk management, including credit approval process, risk appetite, back book management.

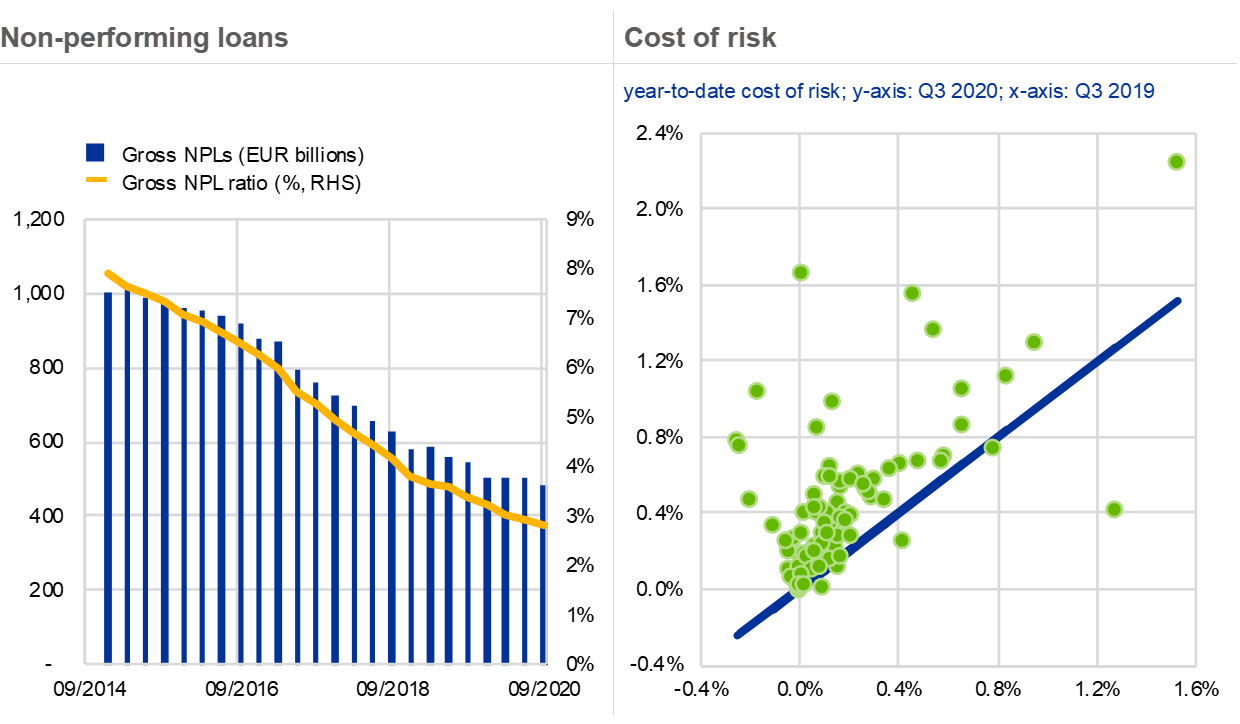

To some degree, the lag in the reaction of non-performing loans (NPLs) is to be expected, and the increasing cost of risk, a measure of provisioning, is a sign that banks are preparing for asset quality deterioration. But over the course of 2020 we did develop specific concerns about identifying, measuring and managing credit risk.

We promptly communicated these concerns in letters to banks in July (on operational preparedness) and December 2020 (on credit risk). Within the SREP, we have taken qualitative measures in the specific areas I have just described. Clearly, asset quality deterioration remains our main concern for 2021 and is a supervisory priority we will follow up on.

Chart 9

Asset quality deterioration has not yet materialised: mild uptick in NPL ratio so far and provisions increasing.

Source left-hand chart: Supervisory reporting.

Note left-hand chart: Sample comprises 110 SIs as of Q3 2020.

Source right-hand chart: COVID-19 supervisory reporting as of Q3 2020.

Notes right-hand chart: Sample comprises 97 SIs. The cost of risk is the impairment or (-) reversal of impairment on financial assets not measured at fair value through profit or loss divided by total loans and advances at the end of the fourth quarter of the previous year and is expressed as a percentage.

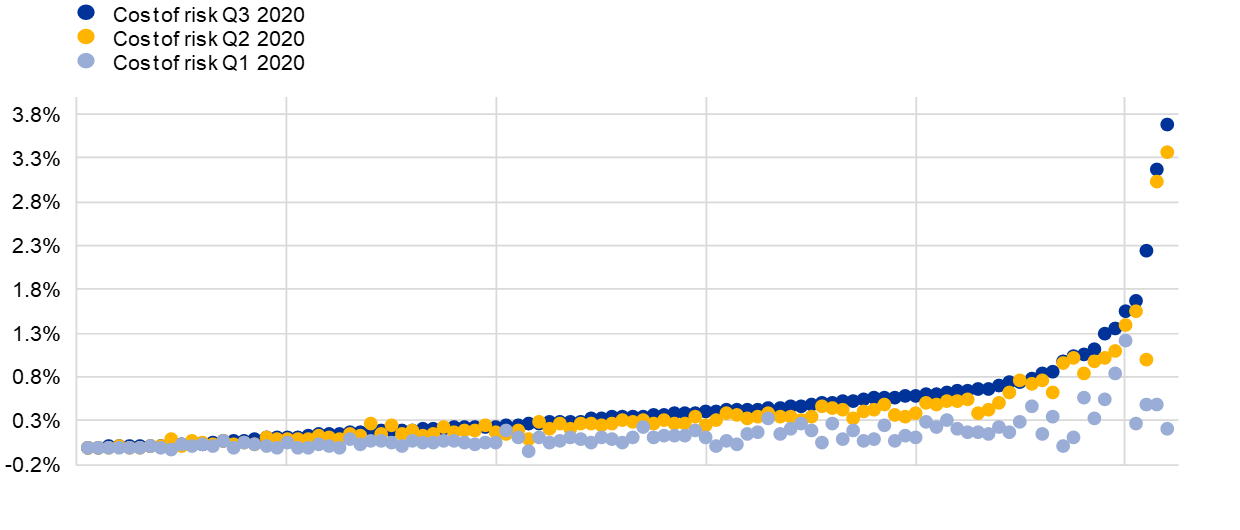

The evolution of provisioning in 2020 confirms the market consensus: with their provisioning in the second quarter, banks absorbed most of the cost of risk they envisaged taking on due to the pandemic. But our expectation is that the social restriction policies that became necessary during the last quarter of 2020 – and that are still in force – will demand additional efforts from banks. We will monitor these efforts closely and expect them to be reflected in the data for the fourth quarter of 2020 and going into 2021.

Chart 10

Most provisions were taken in H12020. The winter restrictions may demand further efforts in Q4 and into 2021.

Cost of risk

(Percentages)

Source: COVID-19 supervisory reporting as of Q3 2020.

Note: Sample comprises 104 SIs. The cost of risk is the impairment or (-) reversal of impairment on financial assets not measured at fair value through profit or loss divided by total loans and advances at the end of the fourth quarter of the previous year and is expressed as a percentage.

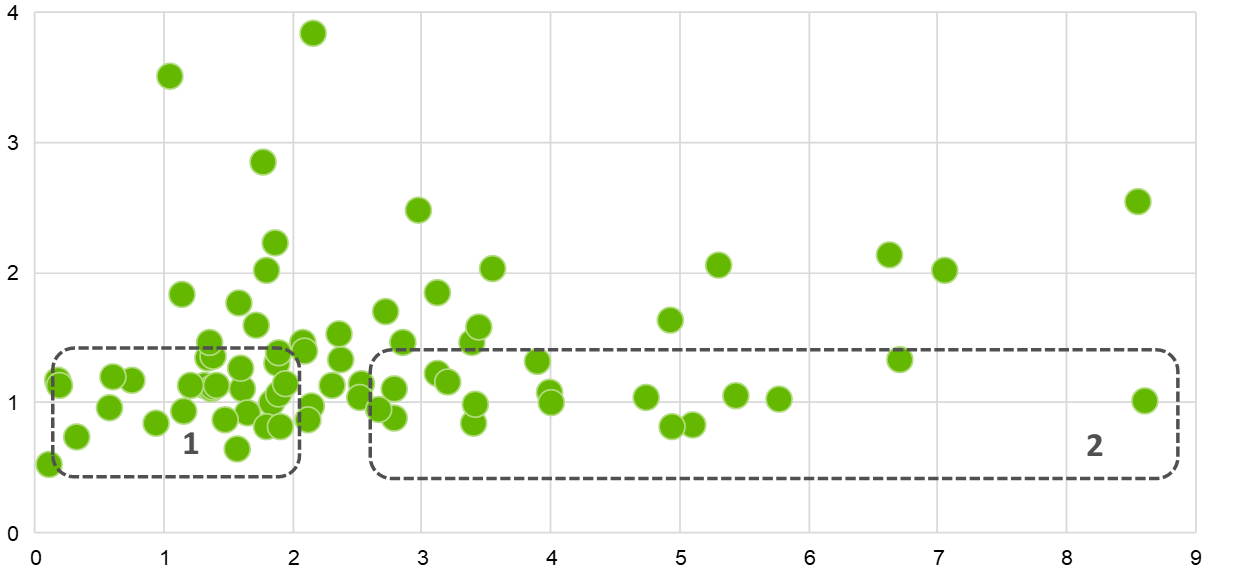

Data for the third quarter of 2020 confirm a concern we already flagged in December. The way in which banks are preparing for asset quality deterioration varies widely and could, in some cases, be insufficient.

Stage 2 classifications have increased, to a limited extent, for many banks in the sample, showing a tendency to refrain from identifying significant increases in credit risk within the loan book. For several banks, this has been coupled with low increases in provisions, which remains a point of supervisory attention.

Chart 11

We observe a wide spectrum of provisioning…

Cost of risk change vs. stage 2 % change

(x-axis: cost of risk growth factor; y-axis: IFRS 9 stage 2 loan ratio growth factor)

Source: COVID-19 supervisory reporting as of Q3 2020.

Note: The boxes (outlined areas) do not indicate any official threshold used by the ECB. They are aimed at identifying ranges of behaviour. A number of banks (box 1) reported a low increase in stage 2 classifications (significant increase in credit risk) and in provisioning, while some others (box 2) increased provisions, but did not increase stage 2 classifications (e.g. provisions via model overlays). Horizontal axis: cost of risk (CoR) in first nine months of 2020 divided by CoR in first nine months of 2019. A value of 2 means a 100% increase in CoR in Q3 2020 compared with Q3 2019. Vertical axis: IFRS 9 stage 2 ratio in Q3 2020 divided by same ratio in Q4 2019 (taken as the starting point before the COVID-19 crisis). IFRS stage 2 ratio = ratio of stage 2 loans to total loans subject to staging at the end of the quarter. A value of 1 means the IFRS 9 stage 2 ratio was unchanged between Q4 2019 and Q3 2020. Sample comprises 75 SIs.

This observation is shared by our colleagues on the central banking side. Banks’ provisions appear to fall below the levels observed in other jurisdictions (such as the United States), below the levels reached in response to the financial crisis and, more generally, below the levels predicted by historical elasticities to macroeconomic developments[1].

Some of the aggregate evidence on under-provisioning may be explained by the unique features of this crisis, including the unprecedented public support, the specific role of savings and disposable income during pandemics, and the negative impact of COVID-19 being concentrated in specific vulnerable sectors. Nevertheless, we must remain vigilant to banks’ practices leading to under-provisioning.

Back in November 2020, we identified that some IFRS 9 models on probabilities of default had become far less sensitive to changes in GDP, which might indicate that banks have implemented model changes aimed at artificially reducing the measurement of credit risk. We plan to monitor developments in this area, as these interpretations may account for our finding that 2020 provisions were lower than historical elasticities would predict.

Chart 12

… and some concerning model changes.

Sensitivity of IFRS 9 probability of default functions to GDP changes

(x-axis: GDP growth rate; y-axis: PD 12-month scaled to 1 in the baseline scenario)

Source COVID-19 supervisory reporting as of Q2 2020.

Note: Sample comprises 25 SIs. IFRS 9 probability of default (PD) models refer to exposures to large corporates, sovereigns and institutions. Blue lines represent December 2018 values, yellow lines represent values from June 2020.

In our letters to banks in July and December 2020, we emphasised the importance of identifying borrowers’ financial difficulties at an early stage. In our view, it is crucial that banks consider all available evidence and reflect on developing new alternative credit risk indicators which factor in the pandemic environment and the deployment of broad-based moratoria.

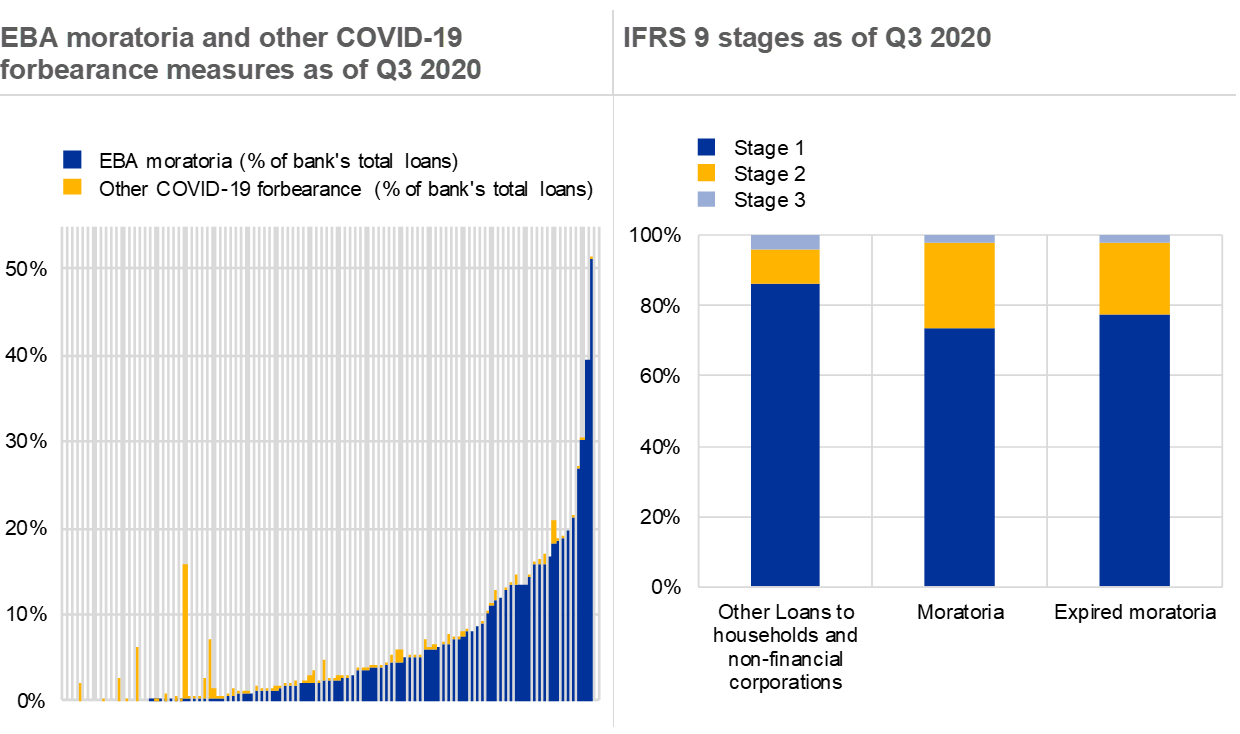

Several authorities and standard-setters, including ECB Banking Supervision, have stressed that moratoria and other forms of COVID-19-related forbearance should not be taken as justifications to postpone the assessment of unlikely-to-pay conditions.

While moratoria and other support measures have provided banks and borrowers with vital breathing space as the social restrictions were implemented, banks should act early to avoid these measures generating damaging cliff effects when they simultaneously expire. This would risk producing exactly the sort of procyclical dynamics that we managed to avert at the onset of the shock. Higher stage 2 classifications highlight a higher incidence of credit risk being identified among moratoria, but stage 3 classifications are still comparable to the levels in the broader loan book.

Chart 13

Banks should assess unlikely to pay (UTP) borrowers even within moratoria.

Source left-hand chart: Supervisory reporting. Notes left-hand chart: Sample comprises 111 SIs.

Source right-hand chart: COVID-19 supervisory reporting as of Q3 2020. Notes right-hand chart: Sample comprises 106 SIs.

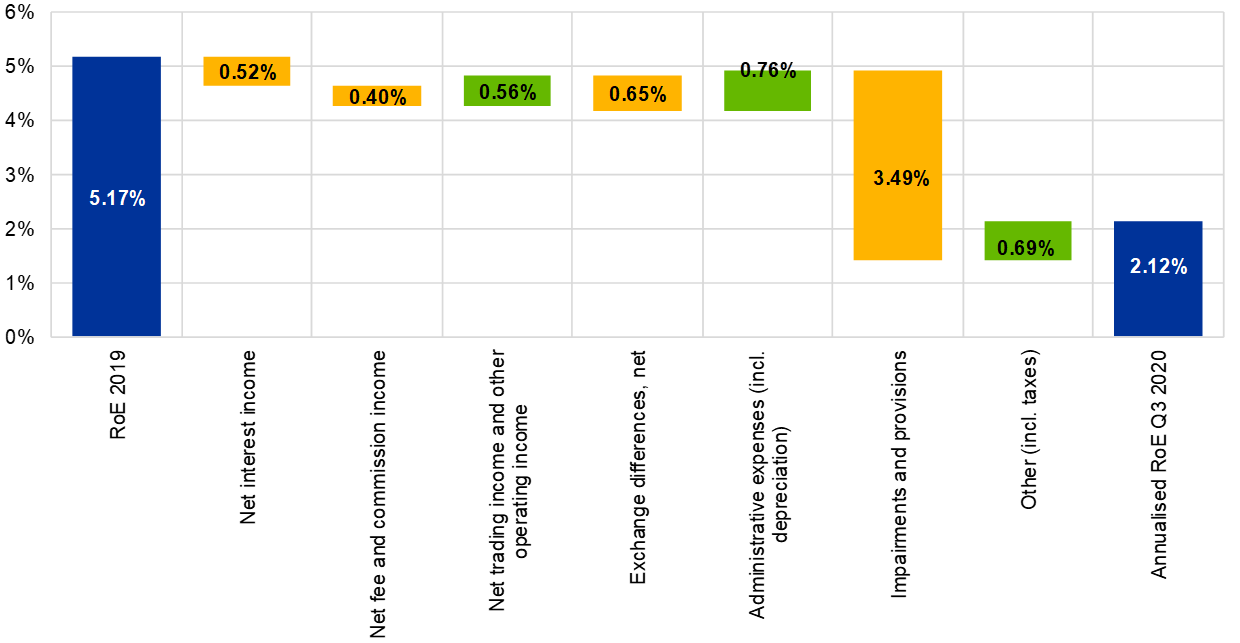

The profitability of supervised banks is projected to rebound only moderately in 2021, to levels that are still low, with a bleak earnings outlook. The provisioning needs that have so far been acknowledged as a result of the pandemic represent the main negative driver in the outlook. As the winter developments are likely to lead to the need for further provisioning, credit risk will weigh further on structurally low profitability in the euro area banking sector. Pressure to address existing vulnerabilities, such as overcapacity in the banking sector and lingering cost inefficiencies, is likely to intensify. Increasing competition from non-banks and the market shift towards greater digitalisation brings opportunities, but also a panoply of increased risks, including IT system deficiencies, cybercrime and operational disruptions in the banking sector.

Chart 14

The pandemic adversely impacted bank profitability compounding existing structural weakness.

Return on equity

Source: Supervisory reporting.

Note: Sample comprises 110 SIs at the highest level of consolidation in Q3 2020 and 113 SIs in Q4 2019. The number of SIs per reference period reflects changes resulting from amendments to the list of SIs following assessments by ECB Banking Supervision.

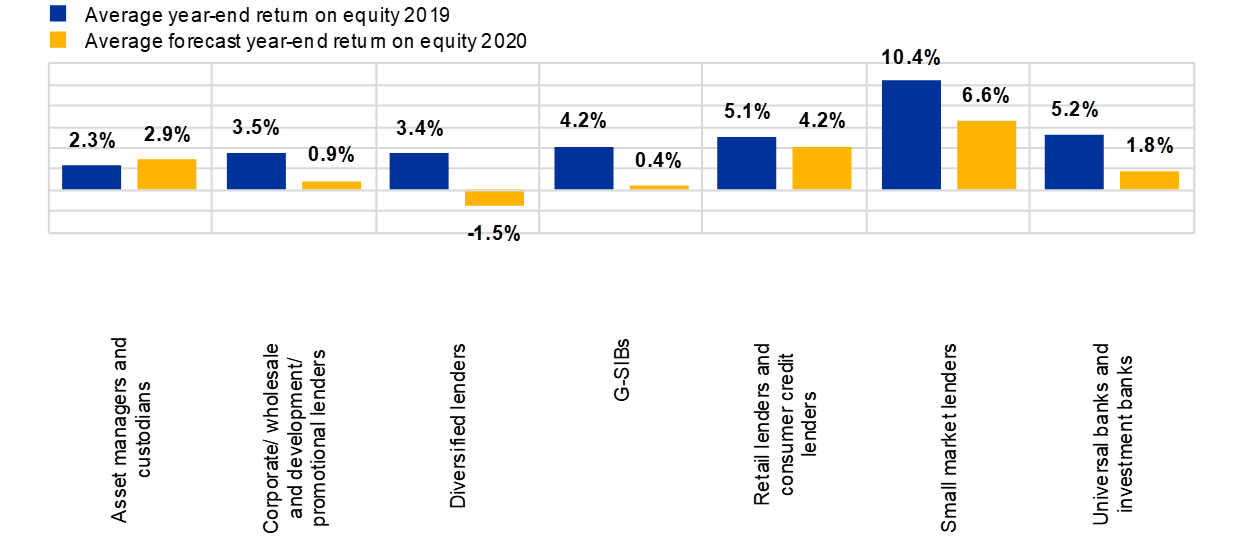

Chart 15

Profitability of diversified and universal lenders is impacted more markedly…

Return on equity

Source: Supervisory reporting and banks’ own estimates of year-end projections as reported in the COVID-19 supervisory reporting as at Q3 2020.

Note: Sample comprises 111 SIs.

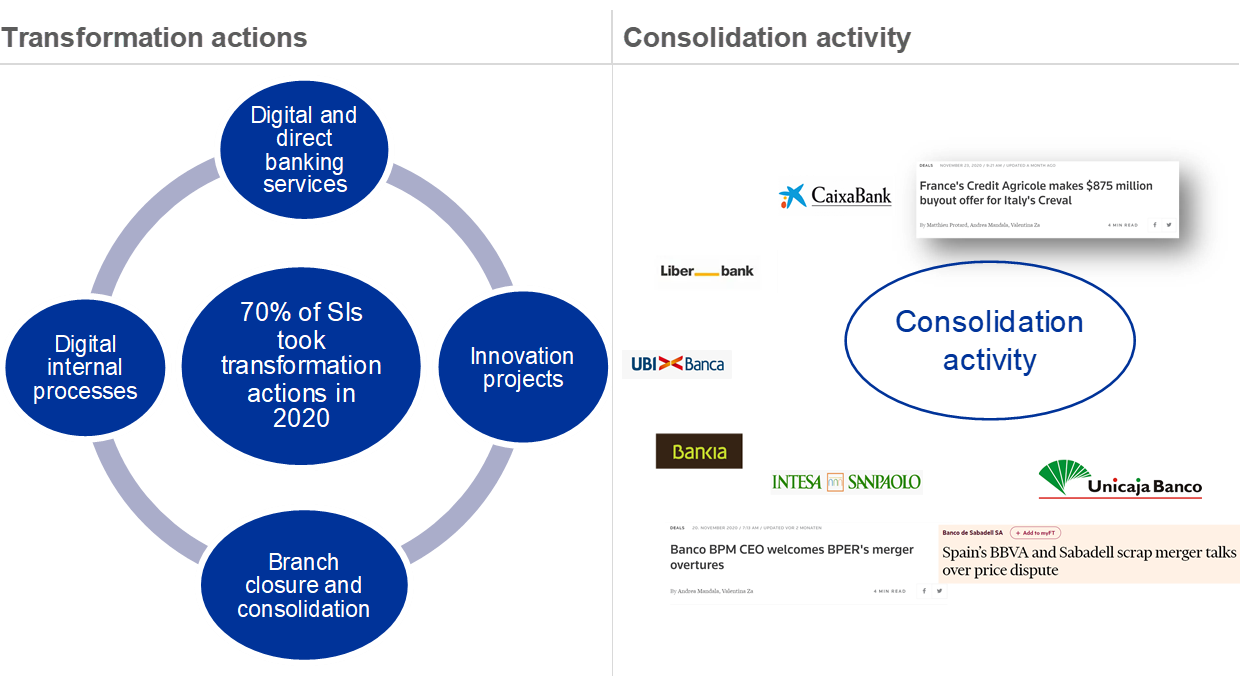

One way to remove excess capacity and restore European banks as attractive investment propositions is through consolidation. We have recently seen some movement here. With our Guide on the supervisory approach to consolidation in the banking sector[2], we set out to clarify our approach and show that it is supportive of well-designed and well-executed business combinations. Consolidation may help address structural problems of overcapacity and depressed profitability and could be particularly beneficial in the aftermath of a recessionary shock. The experience of other jurisdictions, for example in the United States following the great financial crisis, is instructive here.

Drawing on the lessons learned during the pandemic, banks are becoming more alert to the need to enhance cost efficiency and invest in new technologies. Digital technologies not only help banks provide a better service to their clients, they also tackle cost efficiency and transformation issues. Banks using digital technologies to serve their clients remotely may be able to operate fewer branches. In a similar vein, banks may draw on the experience they have gained from managing their staff and premises during the lockdowns. As remote working seems to have proved successful in most cases, banks could consider reviewing their staff and premises policies, with a view to increasing cost efficiency. Several significant banks are engaged in transformation projects which, if successfully executed, might address concerns about the long-term sustainability of their business models.

Figure 2

…but there is an encouraging trend as banks transform and engage in consolidation.

Supervisory priorities and outlook for the euro area banking sector going into 2021

As credit risk from the pandemic has not yet materialised and some concerning practices were identified, scrutiny of credit risk will remain a priority moving into the new year. If banks follow up on our 2020 letters on credit risk and qualitative measures under the SREP, the credit risk picture will clear up in 2021. This, in turn, will allow us to get a better picture of banks’ capital trajectories after months of heightened uncertainty and impaired capital projection capacity.

Capital buffers have been made available due to the frontloading of P2R composition, while our SREP requirements and guidance in total capital remain stable. This full buffer flexibility is at the banks’ disposal until at least the end of 2022 so they can absorb the cost of risk of the pandemic in 2021. Banks should not let concerns about the supervisory reaction to their use of buffers stop them from appropriately measuring credit risk. Let me also stress that, with asset quality becoming more visible and capital projections more reliable, ECB Banking Supervision will, as announced last December, return to the ordinary supervision of dividend distributions and share buy-backs in 2021.

Chart 16

SREP requirements and guidance in total capital remain stable

Source: SREP 2020 values based on 112 SREP decisions applicable from 1 January 2021.

Note: Total SREP capital requirements and guidance” refers to: 8% Pillar 1 + Pillar 2 requirement in total capital + capital conservation buffer + Pillar 2 guidance. It excludes systemic buffers and the countercyclical capital buffer and AT1/T2 shortfalls.

On the structural side, we expect banks to continue along the path of structural transformation that the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted, both in terms of cost efficiency relating to staff and branch management, and in terms of technology adoption. These two avenues will help restore acceptable levels of profitability. In addition, as I said earlier, further consolidation projects, where these can be prudently framed and planned, could help strengthen the long-term sustainability of banks’ business models. We will keep a special eye on governance issues, as the number of outstanding measures from last year’s SREP cycle means this is still one of our greatest concerns.

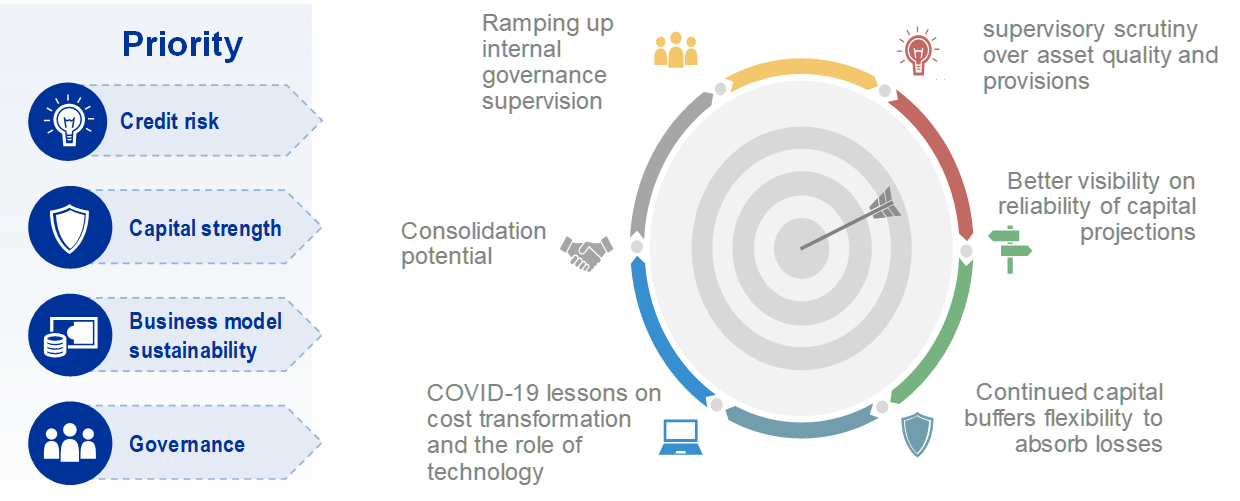

Figure 3

Supervisory priorities for 2021 focus on the impact of the crisis and structural weaknesses

Note: Other priorities include: Improving climate-related and environmental risks management, Basel 3 finalisation preparedness

I now look forward to answering your questions.

* * *

My first question regards dividends. The supervisory dialogue about that should have already started. How is that going? How compliant are banks with your recommendation?

The second question is about the two new countries in the banking union: Bulgaria and Croatia. You guys have started supervising some banks there. How is it going, and in particular, have you found anything that makes you worry about a new Latvia, and I’m referring to anti-money laundering (AML) concerns, given that these countries border what used to be called the Eastern Bloc?

Well, on dividends, yes, you’re right; we just received the feedback from the banks according to our request, and there is some dialogue ongoing. I would say that, in general, significant institutions are all on board with complying with our recommendation. There are some discussions, which are mainly referring to the aggregates, the definition of the aggregates that have to be used in the calculation of what we call the “double guardrail” for setting the constraints on dividend distributions, but the banks are giving positive feedback on their intention to comply with the recommendation.

The cooperation with Bulgaria and Croatia – the participation of Bulgaria and Croatia in the banking union – is going very smoothly. We have included their banks in our regular monitoring following the comprehensive assessment that was completed last year. On AML, of course we have our regular way of factoring AML concerns into our process, also in the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP). For these banks, we also rely on enhanced cooperation with the local AML authorities to get access to all the information which is relevant in order to enable us to be on top of potential issues, especially on the prudential side, so on the aspects of internal controls and governance.

So I have two questions from my side. The first is on liquidity waivers. Mr Enria, what’s your message to banks? You and your colleague Edouard Fernandez-Bollo have done a lot of groundwork in terms of trying to reassure national competent authorities about the – I don’t want to say the word guardrails – but the system, the fact that we live in a European system. Still, it seems like national competent authorities aren’t quite on board yet. So what is your message to banks? Should banks bother applying for liquidity waivers this year, or is it something which is more longer term?

Then the second one is about the nine banks that are indeed tapping their capital buffers, maybe you could tell us a little bit about how that has been seen by investors? Any anecdotal feedback on that? Because I believe there was some reticence on the side of banks to dip into their capital buffers. What’s the experience been with them? Have people lost confidence in them, or are investors all right with it?

As to liquidity waivers, again, we have a setting within the legislation which is, in my view, pretty restrictive, but we still try to give guidance on ways in which we could strive to better manage, also from the supervisory perspective, liquidity on a group-wide basis within the banking union. So banks which are interested in applying for liquidity waivers have the right of doing so under the current legislation, and we will carefully try to address their concerns and look into their requests pretty attentively. Of course, you know that this issue of moving the banking union to become a true domestic market for European banks, it’s not something that will happen overnight. We know that the absence of a deposit guarantee scheme, of a European deposit guarantee scheme, is still a concern in a number of quarters, and will impede a faster move in that direction, but I think there is, as we mentioned also in the paper with Edouard that you refer to, I think we should try to make the current framework work at its best as far as we can.

As to the nine banks, I wouldn’t put a lot of emphasis. Actually, very few banks have dipped into the buffers, and most of those have only slightly dipped into them. There has been an extensive concern that buffers were not being used, that there was a lot of reluctance from banks to use buffers. As I said in my remarks, we need to assess these once the losses, once the deterioration of asset quality, the defaults start to materialise. In that case we will have to see whether banks feel that they can freely use the buffers without being subject to market stigma, or not. I hope this is not the case. Again, our recommendation to banks, as I said today, is that they should actually use the buffers, because that’s the purpose they have been built for.

You spoke about bank consolidation. Now in Italy there is a new CEO at UniCredit, Andrea Orcel. Would the hypothetical consolidation between UniCredit and Monte dei Paschi be seen as positive for the stability of the Italian banking system?

Well, as you can imagine, I cannot comment on a specific case. More generally, I don’t think it’s the business of supervisors to, let’s say, organise weddings between banks and to organise business combinations. I think that the point on concentration, on consolidation, which we have made strongly, is that there is a concern about business model sustainability across several banks in the banking union, and consolidation could be an avenue to address these concerns and put business models on a more sustainable path. We recently issued a guide to clarify our supervisory expectations. I think there was a misunderstanding about the way in which the ECB was looking into consolidation, there was an impression that we would have increased capital requirements as soon as a business combination was proposed to us. We clarified that this was not the case. We also clarified the treatment of so-called badwill, which is particularly relevant now, having seen the depressed valuation of European banks. So I think that we provide clarity and we see that some projects have taken shape and have developed recently, and we do hope that these processes will continue, because we think it’s crucial to address the excess capacity problems that we have been seeing since several years ago.

So I’d like to ask about underwriting risks in the leveraged loan market. Are you concerned about aggressive multiples or capital structures there in general, and if so, will you address this in any way in terms of extra capital charges for banks arranging or buying into some of the most aggressive leveraged loan capital structures?

We have been focused on the risks in the leveraged loan markets for a while. We have seen that this market has developed strongly since 2016-17, and we have seen that, in their search for yield, European banks also started venturing into this market in quite a significant way. In 2017 we issued guidance for our banks, for our significant institutions, to only exceptionally engage in highly leveraged transactions, and to limit the exposures to so-called covenant-lite transactions. Nevertheless, and despite our guidance, we have seen that the exposures to highly leveraged transactions – so where the exposure, the debt is more than six times the earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) – have represented, if I remember well, around 60% of the exposures. Also, the relevance of covenant-lite transactions is still quite high. So we have intensified our pressure on banks, also looking at their stress-testing capability with reference to these exposures, and indeed, we are asking for very attentive risk management and containment of risk in these areas. Where we don’t see adequate responsiveness of the banks to our supervisory pressure, we can also reflect our dissatisfaction in our supervisory recommendations, and eventually in the capital charges for the banks.

Sorry, as a follow-up, has any bank had any extra capital charges already because of this?

Well, we have done a number of on-site inspections which have focused explicitly on leveraged finance, and in many cases we have asked for adjustments in the prudential treatment of these exposures, which has indeed reflected into capital impact.

You said that many banks’ business models were not reliable. That sounds like quite a serious problem looking ahead, but you also said the ECB’s job isn’t to arrange marriages between banks. So what do your qualitative recommendations to these banks that are troubled actually involve, and do you have confidence they will be heeded?

A quick second question. I think you said that banks were artificially manipulating their internal credit risk models; that they’d changed their models artificially. What can you do in that situation? Does the ECB have enough powers to act in that area?

Indeed, one of the key pillars of our SREP assessment is the sustainability of business models, also because the ability to generate profits, to attract investors, is the first line of defence for banks in the case of a shock. At this moment we think that if you look at banks’ valuations and the depressed profitability, which is now – I mean, we have the return on equity below the cost of equity for the large majority of our banks – this is a situation that needs to be remedied. The way in which this needs to be done is by more decisive action on a number of drivers. We made an interesting analysis already, I think three years ago, on banks’ business models, in which we came to the conclusion that the banks which had stronger business models were those which had a strong capacity in terms of strategic steer, so the governance aspect is very important. Investment in new technologies, digital technologies in particular, was a second very important driver. Of course, asset quality was a third element that was very relevant, and cost-efficiency, and reliance on expensive branch networks was the other ingredient. So these are the elements of the puzzle. We are putting increasing supervisory pressure on banks to tackle these challenges, and as I mentioned in my remarks, we noticed that the pandemic, to some extent, has been a catalyst for banks to bite the bullet and start addressing these weaknesses in a more radical way. So we encourage banks to move further in this respect.

Now, on the credit risk models, manipulation is a big word, right? What we notice is that they have flattened in their models the responsiveness of their probabilities of default to decreases in GDP. Now, there could be good justifications for this. It’s the first time that we have a recession which is both so sudden and so harsh, but at the same time there is such a strong reaction of monetary and fiscal policy to support a faster and stronger recovery. So there could be justifications for this adjustment, but it is so massive that we think we need to look more into that. The key point on which we have been zooming in recently is the ability of banks to produce reliable projections on asset quality and therefore on capital, and this is where the focus of our teams will be particularly centred in the coming months.

My first question is in relation to monetary policy’s impact on the banking sector. Yesterday we saw reports of Governing Council members stressing that a rate cut is still an option that they are considering. I was wondering, how do you assess the resilience of the banking system, especially going forward in 2021-22, to still lower interest rates?

My second question is in relation to public debt. We know it’s going to keep rising in 2021. In this context, how urgent do you deem the debate about maybe reforming the Basel III framework, introducing risk weights for sovereign debt held by banks?

The low and negative interest rate environment has of course exercised a negative effect on interest margins, but at the same time it has exercised a positive effect on lending volumes, and also for some time on the trading book asset. Of course, it’s very difficult to look at the counterfactual, so having a very accommodative monetary policy, as I mentioned, has been instrumental to accompany a path for fast recovery and to avoid a massive deterioration of asset quality up to now. So there have been a number of very positive effects on banks from the current monetary policy stance, but of course there is also the effect on interest margins which is relevant. The stress test that we will run, together with the European Banking Authority (EBA), will also try to capture this aspect of the low-for-longer type of interest rate environment, I understand.

With reference to the sovereign exposures of the banks – I understand this is the main focus of your question – so far the risk embodied in these exposures has been relatively muted. The spreads have remained pretty compressed. Banks have increased their exposures, and in particular there are also indirect exposures through the guaranteed loans that have been granted in the response to the pandemic. So there is an increase in the exposure. As we have always said in the past – and this is, by the way, my strong conviction – the point is not so much the relevance of the size of the exposures; the point is the concentration of the exposures on the domestic sovereign. So a point from the supervisory perspective that would be very much welcome is increased diversification of these exposures. The debate in Basel has so far not led to any steps being taken in the direction of fixing this issue from the regulatory perspective, but it’s something that, in any case, we keep monitoring from the supervisory perspective.

I have a question about deposits. Analysts argue that deposits have never been less valuable than now, as interest rates will stay low, even below zero, for a couple of years, and central banks are drowning their financial system with liquidity. My question is how banks should react to that, in your view. Should they avoid attracting too many deposits, or do they have to increase their efforts to pass on negative interest rates even to retail clients with lower deposits? Maybe for the big picture, do you think in general that retail deposits are less important for the stability of banks than they have been in the past?

In general, as supervisors, the concern we have with deposits is when they become too volatile, and that’s not the case at the moment. Of course, we understand that, in the current interest rate environment, attracting deposits means that there are limited margins that could be earned on those deposits, but still, it’s up to the banks to decide their own commercial policies, also in terms of pricing. That’s not something where we would express any specific assessment. So our key point is to make sure that deposits are sufficiently protected, and in particular, the aspect that was more destabilising in the crises of the past is when you see a materialisation of credit risk problems, and the deposits start moving. This is one of the stronger arguments in favour of having European deposit insurance schemes, which ensure that whatever the value is, the value of €1 of deposit is the same across the banking union, so I think that’s the most important focus I would have on the topic.

I have two questions for Mr Enria. The first is about SREP requirements. Could you clarify when they will come back to normal, so they will not be pragmatic any more?

The second question is about bad banks. You proposed a European asset management company (AMC). What do you think about the European Commission’s proposal on national bad banks? Do you think they will be useful in cleaning up banks’ balance sheets, and do you expect to see them operational in the short term?

On the SREP requirements, we will start soon with the SREP 2021 cycle. At the end of this year we plan to complete the new cycle. The stress test that we will soon start, together with the EBA, will lead to also the determination of the Pillar 2 Guidance as well. At the end of the year there will be new SREP requirements and guidance that will be defined and that I hope we will discuss again next year in January with the individual banks’ results as well. We have said, of course, that we will give time to the banks to rebuild the buffers, so at least until the end of 2022. We said more precisely that we will not start to rebuild the buffers before the capital depletion generated by the crisis is over. There will be an issue of deciding the appropriate timing and fine-tuning the appropriate timing according to the development of the coming months, but in any case, we said clearly not before the end of 2022. So that’s a little bit the picture for the SREP, for the P2R and the P2G.

In terms of the issue of asset management companies, I am pleased that the Commission took up the topic of asset management companies in their communication on non-performing loans and on how to deal with the problem. I think that the paper was useful to keep the subject on the table. Let me be clear with you. I hope that there will be no need for asset management companies, so I hope that the relatively rosy projections that we have seen also by market analysts will be the right projections, and that maybe we have been a little bit too gloomy in our assessment of credit risk, but indeed, if we move in the direction of a significant increase in non-performing loans, I think it is important that we start making some preparations in that respect. This dilemma, European versus national AMC, I mean, if you asked my personal opinion, I’ve never been convinced by the arguments against a European AMC. There are people saying that the non-performing loans are very heterogeneous across countries, could not be managed at the European level. What I see is that the major private buyers and managers of European distressed assets are actually in many cases pooling the servicing and the management of these assets for the whole area. If this can be done already by private buyers, I don’t see why an asset management company could not do the same.

There have been concerns that there are forms of State aid having a sort of mutualisation of losses across Member States would be politically very difficult, but in my proposal I’ve always mentioned that you can very well engineer a scheme that does not entail any mutualisation that reallocates potential losses, and by the way, asset management companies, if well designed, should not generate losses in the long-term, but could be reallocated to individual Member States. I’m not convinced of the arguments against European asset management companies, but I think also national asset management companies could be useful. I understand that the idea of European initiatives is not getting traction. That’s fine. Having national asset management companies would also be a positive way forward if we go into a situation in which bad loans start piling up. What I mentioned in my contribution to the debate is that if you go to asset management companies at the national level, in the banking union at least, it would be important to have some common criteria which ensured that the speed and effectiveness with which banks can clean their balance sheet is equivalent, irrespective of the country, the Member State where the bank is headquartered.

I focused in particular on the issue of pricing and funding. These two aspects, in my view, are crucial to provide an important European component and to put banks across the banking union on a level playing field to deal with the issue.

I just wanted to ask about Brexit. Are there any outstanding concerns for euro zone banks, and have enough staff and resources been moved into the EU at this point?

On Brexit, first of all, let me congratulate the negotiating teams that have managed to conclude a difficult deal at the razor’s edge at the end of the year. I think this has been very, very positive. As far as the banks are concerned, we have had a very clear engagement with the banks. We have defined since a long while their target operating model, so where we expect them to be at the end of the transition when they move their business with European customers to the European Union. My impression is that there are still some sticking points in terms of especially the level, quality of the management in particular, which has been moved to the European Union. I think that one key issue for our attention is that we have sufficient strategic and risk management capacity onshore here, and we’re not there yet. For some banks we are, but not for all the banks, so that’s an area on which we are focusing a lot of our attention. The reliance on back-to-back booking and on outsourcing is another area which is of great attention for us, but there has been a very good engagement with all the banks. They know what we are asking of them, and we have seen significant progress also in the final months of last year, so we are encouraged that we will get to the target operating model pretty soon.

I’ve got two questions. The first one, would European banks be more profitable without negative interest rates?

The second one, what do you recommend in terms of remuneration policies?

I think I addressed the first question to some extent in a previous answer. The negative interest rate policy has, of course, a negative effect on the interest rate margins for banks, but it has also positive compensating effects on volumes and on market valuation, on the trading book, and especially, which is very difficult to quantify because we don’t have the counterfactual, it has had an important effect in terms of avoiding an even harsher recession and a much more, let’s say, concerning deterioration in asset quality. All in all, it’s difficult to assess the impact on profitability.

On remuneration we have not been as clear as we have been on dividends, so we have not put specific limits, because there are already quite detailed rules on remuneration, but we made a clear recommendation to banks to exercise extreme moderation in this extraordinary year, especially by relying also on payments in instruments, or delayed compensation. So it’s clear that it’s an area in which we are also engaging quite a lot with banks.

I have two questions for you. My first is regarding credit risk. I was wondering is there a more specific focus on corporate lending versus house lending. It has been reported that you have asked banks for more details in Germany and in France, and I wonder if you had specific concerns for those two economies.

My second question is about staff policies. You mentioned the fact that staff policies of banks could be changed because of the context we all know of. Do you expect job cuts in the European banking sector in the coming months and years?

On credit risk it’s not as easy as corporates versus households. This is a very specific crisis, a very peculiar crisis, which has a very differentiated impact across a different set of counterparts. In the corporate sectors there is a very diverse impact according to sectors. There are sectors which have been heavily hit by the crisis, and other sectors which have been instead even benefiting from the distancing measures and the behaviours that these distancing measures have triggered. Also, we have to keep in mind that the very significant fiscal support measures that we’ll deploy also, thanks to the Next Generation EU package in the coming months and years, might have also a differential effect on different sectors. There could be sectors in particular linked to, let’s say, digital economy, to sustainable investments, to green and environmental-friendly investments that might be benefited from this fiscal expansion and others that could instead be less on the receiving end of the support. There is a very differential effect within the corporate sector. Also, within households, we have not seen a lot of effect, for instance, on traditional residential portfolios, but instead in terms of lending for consumption there have been some segments in which we have identified enhanced risk. There is a lot of differentiation, which has made the traditional modelling and understanding of the credit risk environment quite difficult for us as supervisors, and that has been a point that I have raised also in my remarks.

On staff policies, the cost-to-income, on average, is very high. If I remember well, it’s around 65%, 66%, and it’s been stable for some time now. It is clear that there are banks which have a cost-to-income ratio which is way too high. I mean, for some, very close to 100%, which means that they’re basically not generating sufficient capital. So for these banks, for this tail of banks, efforts on the side of cost-reductions and staff costs, so staff cuts, also will be absolutely necessary.

Thank you for letting me ask a question. I have two, in fact. One is on non-performing loans (NPLs). The extreme case that you gave a few months ago for NPLs was that there could be €1.4 trillion of extra NPLs. What is the base case? Because apparently we’ve already heard from the ECB that it’s looking more likely it will be the base case than the extreme case. It would be good to know what your base case is on that. Also, you mentioned about debt moratoria. Is that your main area of concern, so these loans that are subject to forbearance and moratoria could transform into NPLs?

Second question is on dividends and, how much do you expect the banks to pay out in dividends this year?

On NPLs, I wouldn’t give any specific figure here. I think that we wanted to put on the table in July, when we made our vulnerability analysis, the possibility that in an extremely severe scenario the deterioration of asset quality could have been much higher than the banks were at the time estimating with their, in our view, excessively mild projections. So that was the main point. Now, the €1.4 trillion case is, to be honest, less likely right now. The probability of that scenario has reduced according to the most recent forecasts. We are starting in a short while a new stress test that will be the tool with which we will try to estimate in a more accurate way the potential deterioration in asset quality. Moratoria is a peculiar area of concern, because of course, the delays in payments are one of the main indicators the banks use to classify their customers, and moratoria generate a sort of blindness, lack of visibility in terms of payments. That’s why since the very beginning, since March last year, we have told banks that they should have developed additional indicators, try to understand the quality of their customers and to see through the moratoria to be able to reclassify customers if they are unlikely to pay back their loan. We have not seen a lot of that happening; so that’s an area in which indeed we are focusing a lot of our attention. It was one of the areas of focus of our letter in December. I must say that also the flagging of forbearance cases is something which we were puzzled. We have not seen sufficient loans being reclassified as forborne, and we were concerned because the indicators showed that this was not reflecting the reality on the ground. So these areas are areas in which we are collecting information now from the banks. We ask banks to give us replies to our letter in December by the end of January, and we will analyse carefully these answers.

On dividends, it’s a bit early days. We just received the feedback from banks, and with some of them we are still negotiating and discussing how the aggregates should be calculated and the like, but our very, very preliminary estimate is that the ballpark should be what we, basically, expected, so slightly above €10 billion, so around €10.5 billion, maybe €11 billion in that region. So that’s what we expect in full compliance with our recommendation.

- For more details, see ECB (2020), Financial Stability Review, November.

- Available on the ECB’s banking supervision website.

Europese Centrale Bank

Directoraat-generaal Communicatie

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Duitsland

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproductie is alleen toegestaan met bronvermelding.

Contactpersonen voor de media