- SPEECH

The evidence is in: resilient banks build Europe’s growth on solid ground

Keynote speech by Claudia Buch, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the 2025 EBA Policy Research Workshop on “Bridging capital and growth – the role of financial structures and intermediaries”

Paris, 19 November 2025

Thank you for the opportunity to speak today about the evolution of the European capital regulation framework – how it has changed since the global financial crisis, what we know about its effects and how we can further improve the way we evaluate its impact.[1]

The global financial crisis painfully revealed the need to strengthen global capital rules. Through the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision, policymakers from across the globe worked together to provide a coordinated response. The result, the Basel III standards, was designed with a straightforward purpose: to rebuild confidence by ensuring banks maintain capital and liquidity commensurate with their risks, to limit leverage and to make crises less frequent and less costly.[2] These objectives remain as valid today as they were 15 years ago.

Yet, discussions about capital regulation are once again moving to the foreground. Some argue that the framework has become overly complex or too demanding, while others question whether it strikes the right balance between fostering resilience and supporting growth. Another perspective points to the heightened risks and uncertainties in the financial system, advocating for stronger safeguards and larger capital buffers. It is vital that these debates are grounded in good evidence.

Today, I would like to make four points.

First, the Basel reforms were the right response to the vulnerabilities that had built up in the global banking system before the financial crisis and were then laid bare by the crisis in 2007-08.

Second, the new standards are now being implemented across jurisdictions, including in Europe. This strengthens banks’ resilience against future shocks and makes them better equipped to address the vulnerabilities that are building up today.

Third, evaluations of the post-crisis reforms show that these measures have increased resilience without constraining economic growth or stifling lending to households and firms.

And lastly, as new risks are emerging, we can further improve our evaluation framework to ensure that policy debates remain firmly grounded in the best evidence.

The evolution of capital regulation since the global financial crisis

The global financial crisis of 2008 exposed fundamental weaknesses in regulatory and supervisory frameworks in place at that time. Pre-crisis global capital rules – Basel II – were a key contributor to the vulnerabilities within the system. Banks entered the crisis with too little capital, excessive leverage and insufficient liquidity. The system was overly reliant on external credit ratings, while supervisory tools were limited and often fragmented. Additionally, the perception that some banks were “too big to fail” encouraged excessive risk-taking and unchecked balance sheet expansion.

When confidence in the system evaporated, its fragility and deep interconnectedness became apparent.[3] Shocks spread quickly throughout the financial system and became amplified. Negative externalities were huge. The repercussions of the crisis went far beyond the banking sector. Public finances came under strain, growth weakened, inequality worsened and unemployment surged – leaving long-lasting scars in many countries.

The response that followed was equally far-reaching. Policymakers introduced a comprehensive overhaul of the prudential framework, which included requirements for higher and better-quality capital, new liquidity requirements, a sophisticated architecture of useable buffers and new resolution frameworks.[4] Together, these measures marked a decisive shift towards a more resilient and better-capitalised banking system. The reforms realigned incentives, enabling banks to be better placed to take risks and absorb losses. This supports economic growth and overall welfare.

Higher and better-quality capital

The first and most visible post-crisis change was an increase in the quality of capital. These reforms were agreed in 2010, when the Basel Committee and the Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision endorsed the Basel III package tightening capital definitions.[5]

Before the crisis, many instruments were classified as capital even though they would not be able to absorb losses during a going concern scenario. The Basel III reforms addressed this by tightening the definition of Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital to ensure it truly represents loss-absorbing capital. Deductions from capital related to goodwill, deferred tax assets or minority interests became less generous. As a result, CET1 capital now consists of the highest-quality equity and retained earnings.

At the same time, the crisis revealed weaknesses in the risk-weighting framework. Banks using internal models could assign very low risk weights to certain exposures, which made reported capital ratios look strong even for highly leveraged banks. While capital requirements need to take risks into account, this created scope for an understatement of risks and inconsistency across banks.

But the reforms went further. Basel III introduced a microprudential capital conservation buffer, which requires banks to maintain an additional 2.5% of risk-weighted assets in CET1 capital above the minimum requirement. If a bank falls below this level, its ability to distribute dividends or bonuses is automatically constrained. This incentivises the conservation of capital in good times and provides a cushion to absorb shocks in times of stress.

A second macroprudential buffer – the countercyclical capital buffer – gives authorities the flexibility to mandate the accumulation of additional capital during periods of economic expansion and to release it when the financial cycle turns. Unlike microprudential buffers, which address risks at the individual bank level, the countercyclical capital buffer addresses vulnerabilities across the broader banking system. It helps mitigate the effects of boom-and-bust cycles and makes capital requirements less procyclical.[6]

These were the first steps towards a more dynamic and risk-sensitive framework – one that recognises that capital adequacy is not a static concept. Capital needs to be available and useable when a crisis hits. The reforms thus address the “paradox” of banking regulation,[7] wherein static buffers – if they cannot be drawn down in a crisis – may force the bank to deleverage or compel the supervisor to intervene when capital requirements are breached.

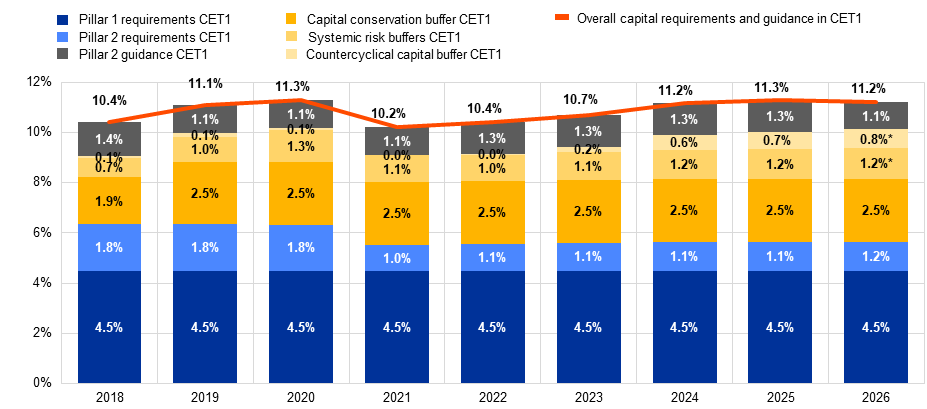

Today, the euro area banking sector remains well-capitalised (Chart 1): the average CET1 ratio stands at around 16% and is thus 3.4 percentage points higher than at the beginning of the banking union in 2014.

Chart 1

Developments in overall capital requirements and Pillar 2 guidance for significant institutions

(percentages of risk-weighted assets)

Sources: ECB supervisory banking statistics and SREP database.

Notes: The sample selection follows the approach outlined in the methodological note for the publication of aggregated supervisory banking statistics. For 2018, the first quarter sample is based on 109 euro area entities, for 2019 on 114 entities, for 2020 on 112 entities, for 2021 on 114 entities, for 2022 on 112 entities, for 2023 on 111 entities, for 2024 on 110 entities and for 2025 on 113 entities. For 2026, the sample is based on 109 entities. The Pillar 2 requirements are applicable from January 2026.

The leverage ratio – a backstop to models

The second pillar of the post-crisis reforms was the introduction of a non-risk-based leverage ratio. Before the crisis, many banks had expanded their balance sheets significantly while maintaining only minimal equity capital. Although their reported risk-weighted capital ratios appeared robust, overall leverage in the financial system had risen to unsustainable levels.

High leverage leaves banks highly vulnerable to even minor losses:[8] a bank with a leverage ratio of 2% – meaning €2 of capital for every €100 of assets – would lose half of its capital if the value of its assets fell by just 1%. To restore its capital ratio, it would need to sell nearly 50% of its assets. Such fire sales can lead to falling prices and force other banks to deleverage, deepening an economic downturn. These dynamics were observed in 2008, when small losses quickly eroded capital and forced large-scale balance sheet contraction across the global banking system.

To mitigate the effects of high leverage, the Basel Committee introduced a minimum leverage ratio of 3%, calculated on total exposures without risk weights.[9] It serves as a backstop – a floor below which capital cannot fall, irrespective of modelled risk weights.

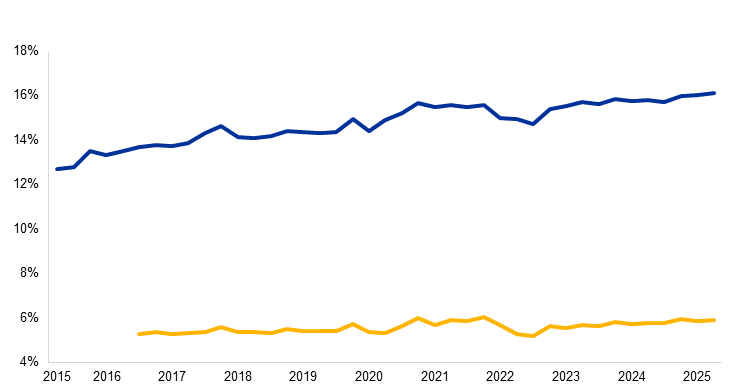

In Europe, the leverage ratio has been fully integrated into the Capital Requirements Regulation. Today, the actual leverage ratio of euro area banks is around 6% (Chart 2). This means that if asset values were to decline by 2%, a bank would lose about one-third of its capital. To restore its capital position, it would need to shrink its balance sheet by around 15-20%, instead of nearly 50%, as was the case pre-crisis. The system is therefore less fragile – but it remains quite leveraged,[10] implying that even modest shocks could still have relatively significant effects on banks’ balance sheets.

This is one reason why supervision in Europe not only focuses on banks’ compliance with key prudential ratios but also takes a comprehensive perspective to assess their risk management, governance and business models and address potential deficiencies.

Chart 2

CET1 ratio and leverage ratio of significant institutions

Source: ECB supervisory banking statistics.

Liquidity and funding standards

The financial crisis revealed that insufficient solvency is not the sole reason banks fail during periods of distress. Many institutions have failed in the past not because they were insolvent, but because they were illiquid. To address this, Basel III introduced two new global standards.

The liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) requires banks to hold sufficient high-quality liquid assets to withstand a 30-day period of market stress. It ensures that banks can absorb short-term liquidity shocks without resorting to fire sales or emergency support from the central bank.[11]

The net stable funding ratio (NSFR) complements the LCR, imposing a more structural requirement: it mandates banks to fund illiquid assets with stable sources of funding, such as long-term debt and retail deposits.

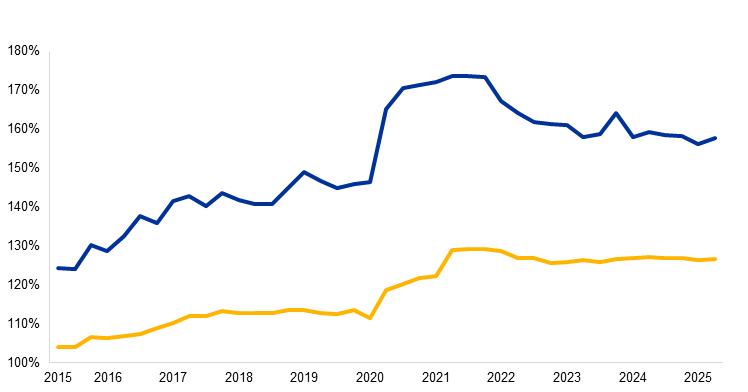

Together, the LCR and NSFR have shifted business models away from excessive reliance on short-term wholesale funding. Today, liquidity positions remain comfortable, with the average LCR standing at around 158% and the NSFR at approximately 127% (Chart 3). Favourable financing conditions are reflected in relatively tight bank bond spreads. However, banks’ growing reliance on market-based funding could pose risks in times of stress.

Chart 3

Liquidity ratios of significant institutions

Source: ECB supervisory banking statistics.

Addressing “too big to fail”

A further lesson of the financial crisis was that some institutions were too big or too interconnected to be allowed to fail. During the crisis, distress spread rapidly through the system, amplifying losses and turning stress in individual banks into a global financial crisis. Yet, consistent frameworks for dealing with failing banks were lacking, requiring ad hoc interventions by fiscal authorities to stabilise the system. The rescue of large institutions came at significant fiscal cost, ultimately placing the burden on taxpayers.

The post-crisis regulatory framework therefore seeks to address these externalities through additional safeguards for systemically important banks, including capital surcharges and measures to improve their resolvability.

Global systemically important banks are now subject to additional capital surcharges calibrated based on their systemic importance.[12] Moreover, they must meet minimum levels of total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC), which consists of instruments that can be written down or converted into equity during resolution.[13] In the European Union, this is mirrored in the minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL).[14]

Together, these measures make resolution more credible and protect public finances. Moving from a “bail-out” to a “bail-in” approach reduces banks’ incentives to take excessive risks – thus better aligning banks’ interests with those of society.

Mitigating model risk and the “finalisation” of Basel III

Around ten years after the global financial crisis, attention turned to another weakness in the regulatory framework – the wide variation in risk-weighted assets reported by banks with similar portfolios. The concern was that internal models, while designed to be risk-sensitive, were producing results that were neither sufficiently consistent nor comparable across institutions. Additionally, internal models often failed to adequately account for structural breaks and systemic effects.

The Basel Committee responded with a comprehensive set of revisions, finalised in December 2017. These included:

- strengthening the standardised approaches for credit, market and operational risk;[15]

- restricting the use of internal models, including prohibiting advanced approaches for certain low-default portfolios;

- implementing an output floor that requires model-based risk-weighted assets to remain below 72.5% of the amount calculated under the standardised approaches;

- overhauling the market risk framework through the fundamental review of the trading book.[16]

This package of revisions, sometimes referred to as “Basel III finalisation”, marked the conclusion of the post-crisis capital reforms, around a decade after the crisis began.

Implementation in the European Union

Designing and calibrating the reforms was only the first step; their subsequent implementation has taken some time. In the EU, the Basel standards have been translated into law through successive iterations of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) and Capital Requirements Directive (CRD). The latest updates – CRR III and CRD VI[17] – complete this process, with provisions taking effect from 1 January 2025. The European Banking Authority (EBA) has been tasked with calibrating the technical details of Basel III implementation.

The full phase-in period for Basel III will end in 2032 – nearly 25 years after the global financial crisis. This extended timeline gives banks ample opportunity to adjust their balance sheets in an orderly manner. For comparison, newly issued residential mortgages in Europe typically have an average initial maturity of 20-25 years.[18] Corporate bank loans, meanwhile, are typically short to medium-term, with the majority maturing within 1-5 years.[19] The extended phase-in period thus provides time for banks to reprice their loans, if needed, and roll over most of their loan portfolios before the new framework is fully effective.

Co-legislators in the EU have introduced transitional provisions and adjustments tailored to the specific structural features of the European banking system, including granting more favourable capital requirements for limited time periods.

One example of such transitional provisions is the output floor. It will be fully phased in only in 2030, and banks in the EU will be able to use lower risk-weights than a full implementation of the output floor would allow on specific exposures until 2032.

An example of adjustments is the SME supporting factor, which lowers the capital charge on exposures to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This deviation from the Basel standards aims to offset potential adverse effects of higher capital requirements on SME lending.

Finally, the implementation of a new market risk framework – the fundamental review of the trading book – has recently been postponed. However, banks are still required to compute and report the relevant regulatory figures to ensure operational readiness and data quality ahead of its full application.[20]

Collectively, these and other similar measures are designed to safeguard the flow of credit to the real economy and allow banks sufficient time to adapt. From a supervisory perspective, it is important that such deviations do not create undue risks or weaken banks’ resilience.

In principle, the Basel III standards apply only to internationally active banks. In practice, European policymakers have chosen to extend the framework to all credit institutions, regardless of size or business model. This is consistent with the Single Market. It ensures a high and consistent level of prudence, but it also means that the framework must cater to a diverse banking landscape.

To address differences across banks, the Basel standards and the EU’s implementation of them embed the principle of proportionality. This means more sophisticated approaches are available for banks with more complex risk profiles, while smaller or less complex institutions may use simpler, standardised methods. Within the EU, small and non-complex institutions (SNCIs) enjoy simplified reporting, disclosure and liquidity requirements under the CRR, reflecting their limited cross-border activity and lower systemic relevance. For example, banks that qualify as an SNCI report only 30% of the data required by the standard reporting requirements.[21]

To address differences across national banking systems, the CRR applies directly and equally across all Member States. The CRD, by contrast, must be transposed into national law – a process that can lead to divergences in the resulting rules through national options and discretions.

This is the architecture that now underpins the prudential framework for European banks. It is more robust, more data-driven and more targeted to relevant risks than what was in place before the crisis. But the key question is: does it work as intended?

What have evaluations and impact assessments shown?

Let me now turn to the evidence on the expected and actual effects of the Basel III package.

It is useful here to distinguish between ex ante impact assessments and ex post evaluations.

Impact assessments are carried out during the design phase of new regulatory requirements to estimate their likely quantitative effects – for example on capital ratios, lending capacity or profitability. These include the quantitative impact studies conducted by the Basel Committee and the EBA. The ECB also carries out similar studies.

Evaluations, by contrast, are conducted after regulatory requirements have been implemented. They assess whether the rules have achieved their intended objectives and look for any unintended consequences. Analysing relevant indicators is a good starting point. But controlling for external factors and accounting for effects that go beyond the individual institution and affect market structures more broadly also require the right analytical tools.[22] Many evaluations have been performed by public authorities, but there is also extensive evidence from academic research.

Impact on capital

As regards the impact on capital, most of the studies summarised here focus on the ex ante phase – they quantify the potential effects of the final Basel III reforms and their implementation in the EU through CRR III and CRD VI.

The studies share a common methodological feature: they assume static balance sheets. This means that it is assumed that banks do not adjust their portfolios in response to the new rules. As a result, these studies may overstate the actual capital impact. In reality, banks respond to regulatory changes well in advance – by retaining earnings, raising capital and adjusting their loan portfolios. Over the long phase-in periods built into Basel III and its implementation in Europe, such adjustments mitigate the initially expected effects on capital ratios and lending.

Overall, the data confirm that the final Basel III reforms strengthen resilience while maintaining European banks’ capacity to support the economy. The evidence is broadly consistent across the different studies.[23]

- Basel III finalisation leads to a moderate, manageable increase in capital needs, concentrated in the largest banks.

- The estimated impact in the EU is lower than under full Basel implementation, reflecting jurisdiction-specific adjustments and the gradual phase-in of certain elements.

- The aggregate capital shortfall is negligible, and capital ratios remain well above regulatory requirements.

The EBA’s impact assessment, which is based on 2023 data, finds the average increase in Tier 1 requirements resulting from the European implementation of the Basel package to be below 4% until 2030 and below 8% in 2033, when transitional provisions are lifted.[24] This relatively moderate impact is still likely to overstate the actual impact because banks continue to adjust their exposures dynamically.

EBA impact assessments using earlier data provide supporting evidence here.[25] These assessments tend to find higher capital impacts for the end of the phase-in period in 2033 than studies using more recent vintages of data. This suggests that, over time, banks adjust their balance sheets to reduce the capital impact of the reforms. This can be considered an intended effect of the reforms if risk management becomes more prudent and better aligns risks and risk controls.

ECB Banking Supervision has conducted similar analyses based on the same underlying data as the quantitative impact studies but using more granular supervisory information and forward-looking assumptions. These exercises yield comparable findings – a moderate overall capital impact concentrated among large, model-intensive banks. On aggregate, the gap between banks’ available capital and their minimum regulatory requirements would be small.

Data collected by the ECB in the context of the 2025 stress test confirm this: the average impact of the reform in the first year (2025) would be close to zero.[26] Capital requirements even declined for some banks.

All in all, the results of these exercises confirm that European banks remain well-positioned to meet the final Basel III requirements. Therefore, capital requirements should not constrain banks’ capacity to lend.

While impact assessments estimate the expected effects of new rules, broader ex post evaluations examine whether the reforms have achieved their objectives and whether there have been any unintended effects. The post-crisis capital framework was designed to strengthen resilience, but it is equally important to evaluate how it has affected the provision of financial services, incentives and behaviour, as well as financial stability.

Impact on lending and cost of finance

The Financial Stability Board (FSB) and the Basel Committee have carried out comprehensive evaluations of the post-crisis reforms.

The Basel Committee’s evaluation of the Basel III rules finds that the framework has significantly increased banks’ resilience without broadly or persistently reducing credit supply.[27] Banks that were not well-capitalised or had less liquidity to begin with have shown greater improvements in solvency and liquidity.

Generally, better-capitalised banks are in a better position to take risks and lend to the real economy. Yet, introducing higher capital requirements could lead to an initial contraction of credit if banks start with insufficient levels of capital. Banks that were weak or even undercapitalised after the crisis tended to respond to higher capital requirements by reducing lending. However, the aggregate supply of credit has not suffered overall because stronger banks and non-bank providers of credit have increased their market share.[28]

From a macroeconomic perspective, model simulations by the ECB have confirmed that the long-term effects of the reforms on GDP growth are positive.[29] In the short-term, growth could be somewhat slower than a no-reform baseline, as banks need time to adjust. In the longer term, however, the positive effect of a less procyclical banking system would dominate.

The FSB has carried out a dedicated evaluation of the impact of the new rules on lending to SMEs and found no negative effects in general.[30] Results differ somewhat across jurisdictions, potentially related to other policies and macroeconomic conditions affecting SME lending. There were some negative temporary effects on SME lending for banks with weaker capital positions before the reforms.

Impact on banks’ costs and efficiency

Theoretically, the impact of higher capital requirements on banks’ funding costs is ambiguous. Ceteris paribus, higher capital lowers banks’ return on equity, which may appear to fall below banks’ cost of capital. But the cost of capital is not exogenous: stronger capital positions also reduce the likelihood of distress, thus reducing risk premia. Another factor that could drive up the costs of debt finance is the withdrawal of implicit funding cost advantages owing to the strengthening of bail-in tools.

Empirically, the effect of stronger balance sheets and improved market confidence seems to dominate. An ECB study found that higher capital requirements under the Basel III finalisation initially reduced CET1 ratios slightly, but banks were then able to rebuild them over time.[31] The analysis also shows that higher capitalisation ultimately lowers funding costs and improves banks’ long-term profitability.

Recent ECB research examined whether stricter capital requirements could constrain banks’ competitiveness, with banks’ profit efficiency serving as a proxy.[32] Using supervisory data for euro area banks, the study found no evidence that the current capital requirements constrain profit efficiency. Microprudential and macroprudential buffer requirements were statistically insignificant in explaining variations in profit efficiency.

But there is a relevant non-linear relationship: up to a certain point, profit efficiency improves as capital ratios rise, with marginal gains tapering off at a CET1 ratio of around 18% and starting to decline beyond that level. This number is higher than the median capitalisation of banks in the sample (around 16%) and substantially higher than the median capital requirements (around 11%), supporting the conclusion that the current requirements are not constraining efficiency. Higher capital is associated with lower interest rate expenses and lower earnings volatility, consistent with stronger balance sheets reducing funding premia and smoothing profits.

Impact of the too-big-to-fail reforms

The FSB’s evaluation of the too-big-to-fail reforms found that larger banks are now more resilient and resolvable, and that the reforms have delivered net benefits to society.[33]

The evaluation emphasised that it is not sufficient to look at indicators in isolation. Withdrawing implicit fiscal funding subsidies through resolution reforms, for example, could lead to increased funding costs for affected banks. This would be an intentional effect of the reforms: banks that might have leveraged up before the reforms because they enjoyed implicit government guarantees would now better internalise the costs of failure. Market-based indicators do indeed show a reduction in implicit funding advantages and systemic risk.

The report also identified areas for further progress, namely ensuring full implementation of resolution regimes, improving transparency around loss-absorbing capacity and continuing to monitor potential spillovers to smaller or domestically important banks.

Impact on risks outside of the banking sector

The FSB’s holistic review of the March 2020 market turmoil and subsequent work on non-bank financial intermediation highlight a structural shift of risk outside the banking system.[34] As banks have become safer, activity has increasingly migrated to investment funds and private credit markets, where leverage and liquidity mismatches can build up.

The FSB’s 2024 Global Monitoring Report on non-bank financial intermediation notes that the sector continues to expand faster than the banking system, underscoring the need for better data and targeted policy responses.[35] The FSB’s peer review of money market fund reforms finds that implementation of the reforms remains uneven and that structural vulnerabilities persist in certain segments of short-term funding markets.[36]

Taken together, these evaluations confirm that the post-crisis reforms have strengthened the core of the financial system. Banks are better capitalised, funding is more stable and the broader economy is more resilient. There is no consistent evidence that suggests any unintended side effects on lending, profitability or competitiveness. On the contrary: well-capitalised and stronger banks are better able to support their customers in good times and in bad.

Looking ahead

The Basel reforms were the response to the devastating effects of the global financial crisis. In today’s financial system, new fault lines have emerged and new vulnerabilities have been building up. Recent reports on financial stability have stressed the threats posed by overvalued asset prices, potentially unsustainable levels of fiscal debt, high leverage and potential liquidity mismatches.[37]

At the same time, debates about competitiveness and the costs of regulation are once again shaping the policy agenda. Some argue that capital and liquidity requirements constrain bank lending and weigh on Europe’s ability to finance growth. Yet these concerns must be judged against the evidence.

More than a decade of analysis shows that the post-crisis reforms have delivered what they set out to achieve: a stronger, more resilient banking system that better supports the economy. Short-term costs of higher capital and liquidity requirements, if any, were modest and mitigated by long phase-in periods. The long-term benefits – in terms of financial stability and sustained lending to the economy – clearly outweigh the short-term adjustment costs.

The new framework has delivered. In strengthening the banking sector through higher and better-quality capital, the Basel reforms continue to be the right response to the vulnerabilities exposed during the global financial crisis. The best way forward is not to reopen the core prudential architecture, but to continue evaluating its effects, broaden its perimeter to address newly emerging risks, and ensure that regulation and supervision remain grounded in the best evidence.

A sound framework for prudential policymaking should be circular – not linear. We need to define objectives, assess likely effects in advance, implement measures and then evaluate after the fact whether those objectives have been achieved. This policy cycle is the essence of evidence-based supervision and financial sector policies. But the infrastructure for policy evaluation has not always kept pace with the speed of change in finance and technology.

The international community, including the FSB, the Basel Committee and the Bank for International Settlements, has already made important progress.[38]

But more work is needed, and three priorities stand out.

First, systematic learning. Evaluations should not be one-off exercises, but a continuous process built into a policy cycle. This means clearer baselines, better documented objectives and agreed indicators to monitor whether objectives have been achieved.

Second, stronger data infrastructure. High-quality, consistent and shareable data are essential. Ongoing efforts in Europe to harmonise and digitalise supervisory data – for example through the EBA’s Integrated Reporting Framework and related ECB initiatives[39] – are important steps forward.

Third, collaboration and open communication. Supervisors, central banks and academics should work more closely together to pool expertise and ensure that decisions are informed by empirical evidence. Structured exchanges and repositories that aggregate and compare studies can help build cumulative knowledge rather than isolated results.

A well-designed regulatory framework provides the predictability that investors and banks need to plan and innovate. It ensures that European banks remain resilient and well-positioned to support growth in the real economy in challenging times.

I am grateful to Skirmantas Dzezulskis, Korbinian Ibel, Massimo Libertucci, Massimiliano Rimarchi and John Roche for their comments and support in preparing this speech. All errors and inaccuracies are my own.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2011), Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems, Bank for International Settlements, June.

Hellwig, M. (2009), “Systemic risk in the financial sector: an analysis of the subprime mortgage financial crisis”, De Economist, Vol. 157, July, pp. 129-207.

Financial Stability Board (2011), Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions, October.

BCBS (2010) “Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision announces higher global minimum capital standards”, 12 September

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2010), Guidance for national authorities operating the countercyclical capital buffer, Bank for International Settlements, December.

Hellwig, M. (2010), “Capital Regulation after the Crisis: Business as Usual?”, Preprints of the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, No 2010/31, Bonn, July, p.9.

Hellwig, M. (2021) “Twelve Years after the Financial Crisis—Too-big-to-fail is still with us”, Journal of Financial Regulation, Vol. 7, Issue 1, March, pp. 175-187.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2014), Basel III leverage ratio framework and disclosure requirements, Bank for International Settlements, 12 January.

Erik Thedéen (2024), “Charting the course: prudential regulation and supervision for smooth sailing”, keynote speech at the Institute of International Finance Annual Membership Meeting, Washington DC, 23 October.

Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/61 of 10 October 2014 to supplement Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and the Council with regard to liquidity coverage requirement for Credit Institutions (OJ L 11, 17.1.2015, pp. 1-36).

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2013), Global systemically important banks: updated assessment methodology and the higher loss absorbency requirement, Bank for International Settlements, July.

Financial Stability Board (2015), Principles on Loss-absorbing and Recapitalisation Capacity of G-SIBs in Resolution, 9 November.

While both TLAC and MREL aim to ensure that banks have sufficient liabilities to absorb losses and support resolution, they are not identical. TLAC is a global standard set by the Financial Stability Board and applies only to global systemically important banks. MREL, by contrast, is an EU requirement under the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive and applies to all EU banks.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2017), Basel III: Finalising post-crisis reforms, Bank for International Settlements, December.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2019), Minimum capital requirements for market risk, Bank for International Settlements, January.

Regulation (EU) 2024/1623 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2024 amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 as regards requirements for credit risk, credit valuation adjustment risk, operational risk, market risk and the output floor (OJ L, 2024/1623, 19.6.2024) and Directive (EU) 2024/1619 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2024 amending Directive 2013/36/EU as regards supervisory powers, sanctions, third-country branches, and environmental, social and governance risks (OJ L, 2024/1619, 19.6.2024) (adopted June 2024).

European Mortgage Federation (2025), Quarterly Review of European Mortgage Markets for the first quarter of 2025, Table 3, “Average maturity of new residential mortgage loans in Europe”.

Loans to non-financial corporations show the bulk of new lending with original maturities between one and five years. See ECB Data Portal, Bank interest rate statistics – new business.

The European Commission has postponed the application of the new market risk framework (FRTB) by an additional year, from 1 January 2026 to 1 January 2027, under a new Delegated Act adopted following a targeted public consultation. This decision was taken under the CRR empowerment to preserve the international level playing field, given that several major jurisdictions have not yet finalised or announced timelines for implementing the FRTB standards. While the binding Pillar I requirements are deferred, banks must continue to compute and report FRTB metrics for reporting and output-floor purposes, ensuring operational readiness ahead of full implementation. See European Commission (2025), Questions and Answers: Postponing market risk requirements to preserve the international level playing field, 12 June.

EBA (2025), Report on the efficiency of the regulatory and supervisory framework (EBA/REP/2025/26), October.

Financial Stability Board, (2017), Framework for Post-Implementation Evaluation of the Effects of the G20 Financial Regulatory Reforms, July.

EBA (2024) “Basel III monitoring exercise results based on data as of 31 December 2023”, EBA/REP/2024/22; BCBS (2024) “Basel III monitoring report, October 2024”. Results for the BCBS Basel Committee, EBA and ECB exercises are drawn from reports using data for the fourth quarter of 2023the 2023Q4 vintage of data. This ensures full comparability across sources, as all three assessments refer to the same reference date and underlying sample. The BCBS Basel Committee has since published monitoring exercises using more recent data, but; however, the data for the fourth quarter of 2023 2023Q4 vintage provides the most consistent basis for comparison of cross-jurisdictional results in this context.

EBA (2024), Basel III monitoring exercise results based on data as of 31 December 2023 EBA/REP/2024/22, October.

See Table 5 in EBA (2024), Basel III monitoring exercise results based on data as of 31 December 2023 EBA/REP/2024/22, October.

ECB (2025), 2025 stress test of euro area banks – Final results, August.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2022), Evaluation of the impact and efficacy of the Basel III, Bank for International Settlements, December.

Financial Stability Board (2021), Evaluation of the Effects of Too-Big-To-Fail Reforms, April.

Budnik, K., Dimitrov, I., Gross, J., Lampe, M. and Volk, M. (2021), “Macroeconomic impact of Basel III finalisation on the euro area”, Macroprudential Bulletin, No 14, European Central Bank, July.

See Financial Stability Board (2019), “FSB publishes final SME financing evaluation report”, press release, 29 November.

Budnik, K., Dimitrov, I., Giglio, C., Groß, J., Lampe, M., Sarychev, A., Tarbé, M., Vagliano, G. and Volk, M. (2021), “The growth-at-risk perspective on the system-wide impact of Basel III finalisation in the euro area”, Occasional Paper Series, No 254, ECB, July.

Profit efficiency is defined as the ratio between observed and potential profits given input prices and outputs. See Behn, M. and Reghezza, A. (2025), “Capital requirements: a pillar or a burden for bank competitiveness?”, Occasional Paper Series, No 376, ECB, October.

Financial Stability Board (2021), Evaluation of the effects of too-big-to-fail reforms, March.

Financial Stability Board (2020), Holistic Review of the March Market Turmoil, November.

Financial Stability Board (2024), Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation 2024, December.

Financial Stability Board (2023), Thematic Review on Money Market Fund Reforms, 2024.

See ECB (2025), Financial Stability Review, May and IMF (2025), Global Financial Stability Report – Shifting Ground beneath the Calm, October.

Buch, C. (2025), “Financial stability, supervision and regulation: building a 21st century infrastructure for better, evidence-based policymaking”, keynote speech at the BIS Innovation Summit, 10 September; Financial Stability Board (2017), Framework for Post-Implementation Evaluation of the Effects of the G20 Financial Regulatory Reforms – Technical Appendix, July; and Bank for International Settlements, Financial Regulation Assessment: Meta Exercise.

See Section 5.2 of ECB (2025), ECB Annual Report on Supervisory Activities 2024.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts