Foreword by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB

Five years on, the benefits of European banking supervision are now evident. Supervisory practices have converged from 19 national models to one European one. And more harmonised rules and increased transparency have led to a more level playing field for banks in the euro area.

Supervisors now have a more comprehensive view of the banking system. Banks across the euro area are now being compared with a large number of their peers, leading to effective benchmarking in terms of business models and risk profiles. At the same time, cross-border linkages and spillovers can also be monitored more easily, which has strengthened not only our understanding of bank-level risk, but also of systemic risk originating in the banking sector.

These benefits have been instrumental in making the European banking sector more resilient. Banks have increased their CET1 ratios from 11.3% at the end of 2014 to 14.1% in 2018. Progress has been made in reducing legacy assets, with non-performing loans (NPLs) falling by around €300 billion over the same period. And funding and liquidity are also more stable than they used to be.

Banks continue to face some key challenges. Profitability remained low in 2018, which affects the capacity of banks to lend to the economy. Between 2016 and 2018, better-performing banks in the euro area offset lower interest margins by expanding credit, while worse-performing banks deleveraged instead.

Reducing overcapacity and high costs improves profitability. To the same end, it is necessary to further reduce the remaining stock of NPLs as well as the hidden losses and uncertainty associated with the valuation of certain complex financial assets – including, but not limited to, level 3 assets. Looking forward, banks, supervisors and regulators need to continue to work together to address these issues, while ensuring that banks adhere to high risk-management standards.

It is equally important to establish a consistent regulatory and institutional framework for robust cross-border integration. A more integrated banking sector would encourage cross-border consolidation and deepen private risk-sharing within the euro area, creating a more stable macroeconomic environment. Regulators and supervisors should push further towards a more unified prudential framework that impedes the ring-fencing of regulatory capital and liquidity.

These efforts go hand in hand with the necessary process of completing the banking union. European banking supervision should be supported by a strong resolution framework and effective deposit insurance scheme to ensure that the integrity of the single banking market remains unchallenged.

Introductory interview with Andrea Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board

You took up the position of Chair of the ECB’s Supervisory Board in January 2019. How will you approach this important task?

First of all, Danièle Nouy, Sabine Lautenschläger and all our colleagues – both here at the ECB and in the national competent authorities (NCAs) – have done a great job of establishing a well-functioning organisation. So I do not have to re-invent the wheel. High standards of supervision will have to be maintained, following the rigorous and demanding approach defined in the set-up phase.

Establishing a single supervisory mechanism has been a major step forward, but we have to acknowledge that we still do not have a truly integrated European banking market. Progress in this area will require the removal of legislative barriers, which is not our task, of course. Still, I think we have to do all we can to achieve progress towards the banking union as a single jurisdiction – a single jurisdiction with regard to banking regulation and supervision, that is. This would lay the foundation for a true domestic market for European banks.

The one thing we must remember is who we are working for: European citizens, depositors, investors, borrowers and the economy at large. Our work must benefit them, and we are accountable to them. This is something I take very seriously, and I see good reasons for being as transparent as possible. People must be able to understand what we do and how it benefits them. Banks must be able to understand and anticipate our policies and actions. And the same is true for investors. We now live in a “bail-in world”; if a bank gets into trouble, its investors will have to take losses. For that reason, they need to better understand the risks they take.

Right at the start of your term, you had to deal with a bank in trouble. How was your first experience with the new European framework for crisis management?

What struck me most was the commitment of our staff. Everyone worked very hard, throughout the Christmas and New Year period. And everyone knew what was at stake and how much the woes of a bank can affect people’s lives. That’s what counts in a crisis. All the processes ran smoothly, and all the authorities involved worked together well.

That said, there is some room for improvement. When we supervisors deal with a crisis, we have to work within the boundaries set by existing regulation. And regulation still differs from country to country. The Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD), for instance, has not been uniformly transposed into national law. Likewise, each country has its own insolvency laws. This means that the tools we can use in a crisis are not the same in all countries. And we cannot always be certain that a smooth exit from the market can be ensured in all cases. This is a problem, not least in the case of cross-border banks. The lack of arrangements for liquidity in resolution is another issue that has recently been highlighted. So, we still have some work to do in order to prepare for future crises.

Looking ahead, the next big change on the horizon is the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union. What is your view on this?

To me, Brexit is a very sad event – not least because I studied in the United Kingdom and then lived in London for 12 years. And speaking from that experience, I can also say that the European Union is not always accurately portrayed in the United Kingdom. Many people seem to overestimate the costs – and underestimate the benefits – of a united Europe.

As for the banking sector, Brexit will bring a lot of change. Quite a number of banks will relocate to the euro area, and this will transform the banking landscape. This raises plenty of questions – how to regulate and supervise third-country branches or investment firms is just one of them. Banks, regulators and supervisors have had to make many preparations for Brexit, and we will have a great deal to do post-Brexit. Nevertheless, I am confident that we will rise to the challenge, also thanks to our effective cooperation with the supervisory authorities in the United Kingdom.

What other challenges do banks face?

Well, there is certainly no lack of challenges for banks. They need to further clean up their balance sheets, they need to rethink their business models, they need to improve their governance, and they need to ensure their resolvability. And these are just the challenges of the past and the present.

Looking ahead, banks should also keep a close eye on what’s happening in the markets. Liquidity has been abundant and cheap for quite some time now. Together with low profits, this has induced banks to take on greater risks. But they should be careful; high asset valuations and compressed risk premia should not be taken for granted. At some point, things may change, and such a change can come very suddenly. Risk and term premia could suddenly increase and hurt banks in many ways, potentially affecting their profits, liquidity and capital. Funding and market risks are likely to become more material going forward. We supervisors take these risks very seriously, and so should banks.

You just mentioned governance as something banks need to work on. How important is this?

Banks now hold more and better capital, more liquidity, and have reverted to more stable sources of funding. However, all this is of little value if a bank suffers from poor governance, short-sighted leadership and a problematic culture. There are two things that bankers must keep in mind. Short-term profits should not be the driving force of bank operations; keeping banks in business long term is what counts. Sustainability is key. Besides being unacceptable from a societal perspective, short-term profits generated by causing long-term detriment to customers, shareholders and taxpayers are not in the interest of the banks themselves. The recent string of scandals and money laundering cases are a case in point.

It has become conventional wisdom that these are difficult times for banks. What can we learn from those banks that are still thriving?

In the euro area, there are indeed a number of banks that are performing better than their peers. What do these banks have in common? At first glance, not much: they are all very different from one another. It seems that there is no “golden” strategy for becoming profitable. But having a strategy is of the essence. The one thing that unites these successful banks is that they excel at what we call strategic steering. They are able to formulate a strategy and to pull it off. It’s not just what they do, it’s how they do it. This is the lesson they offer.

We also have to acknowledge that there is still a structural problem in European banking markets: many banks have been bailed out, but not so many have actually left the market. As a result, Europe still seems to be overbanked, which is reflected in profitability. In other industries, consolidation has been key in eliminating the excess capacity accumulated in the run-up to the crisis.

On the subject of changes in market structure – what is your take on digitalisation? Challenge, opportunity or both?

Technological change is always a complex process that is hard to predict. But I do see opportunities. Digitalisation can help banks to become more efficient and unlock new sources of revenue; it facilitates leaner and faster processes and enables banks to offer customers a better service and new products. If banks manage to seize these opportunities, they will benefit. But if they don’t act, others will – be they small and agile fintech start-ups or well-established tech giants. That’s the challenge for banks.

Surely it is not the task of regulators and supervisors to protect incumbent banks from more efficient competitors. That said, we still have to deal with new risks – cyber risk being the most obvious example. We have to keep a close eye on such new risks and assess whether they require us to adapt the rules. At the same time, digitalisation can help regulators and supervisors become more efficient and reduce compliance costs, especially for smaller and simpler firms. In other words, there are opportunities for us as well.

Adapting the rules has been the leading theme ever since the crisis. What is your view on regulatory reform – has it gone too far, as some claim, or not far enough?

The reform was needed. The crisis had revealed a lot of gaps in the regulatory framework, and we had to close them. I believe the package developed at the G20 level is a balanced one: it has significantly enhanced the safety and soundness of banks, with requirements calibrated and phased in to avoid unwarranted effects on lending and real growth. Some jurisdictions went beyond the requirements set by international standards in some areas and are now reconsidering these choices. In general, I think we should resist pressure to alleviate requirements in good times. As I said before, banks must resist short-term thinking – the same should apply to regulators. We need to think about the long-term stability of the system and avoid pro-cyclical approaches to rule-making.

That said, it is true, of course, that the revised rulebook is fairly complex. So we do have to monitor its effects, and adjust it if necessary. But the priority now must be to finalise the implementation of the reforms consistently around the world.

In Europe, the banking package is about to be finalised and will shape the regulatory landscape for years to come. Are you happy with the outcome?

The banking package is a very important piece of legislation, not least because it implements the Basel standards into European law. While the overall assessment is positive, there are some areas in which the proposed legislation deviates from international standards. This is the case for some technical details of the leverage ratio, the net stable funding ratio and the new rules for banks’ trading books. So the global playing field will not be as level as it could have been.

Turning to the European Union, my view is that the banking package could have been more ambitious in pursuing the objective of a truly integrated banking sector, at least within the banking union. If we aspire to a single jurisdiction for banking, we must overcome the instinct to ring-fence. Banking groups must be able to freely allocate their regulatory capital and their liquidity within the euro area. Unfortunately, the banking package maintains a narrow national scope with respect to waivers from capital and liquidity requirements within banking groups. I hope the legislators will reconsider their approach in the near future as further steps are taken towards completing the banking union.

What else needs to be done in order to move closer to a truly European banking sector?

It is clear that in the absence of a genuinely European safety net, national authorities will remain reluctant to allow the integrated management of capital and liquidity within cross-border groups operating in the banking union. Some progress has been made in establishing a backstop for the Single Resolution Fund, but the political debate on the establishment of the third pillar of the banking union, the European deposit insurance scheme, remains fraught with difficulties. I believe the polarisation between the “risk reduction camp”, which argues that risks should go down before common guarantees are set up, and the “risk-sharing camp”, which argues that the time is now ripe for integrated deposit insurance, is misleading. The two objectives are interlinked. Hence, the European Union should do what it is good at and come up with a clear roadmap. This roadmap should acknowledge how closely connected the remaining elements of reform are. This would allow us to make progress on all those elements in lockstep.

1 Implementing the SSM model of supervision

1.1 Credit institutions: main risks and general performance

Main risks in the banking sector

In 2018, a broad-based expansion in euro area economic activity supported banks’ profitability and balance sheets

ECB Banking Supervision, in close cooperation with national supervisors, conducted its annual risk identification and assessment exercise, and updated the SSM Risk Map, which depicts the main risks faced by euro area banks over a two to three-year horizon, accordingly. During the period under review, a broad-based expansion in euro area economic activity supported banks’ profitability and their balance sheets. This helped to improve the resilience of the euro area banking sector and mitigate some of the related risks, in particular those related to legacy non-performing loans (NPLs) and the low interest rate environment. Nevertheless, the current aggregate level of NPLs in the euro area remains far too high by international standards.

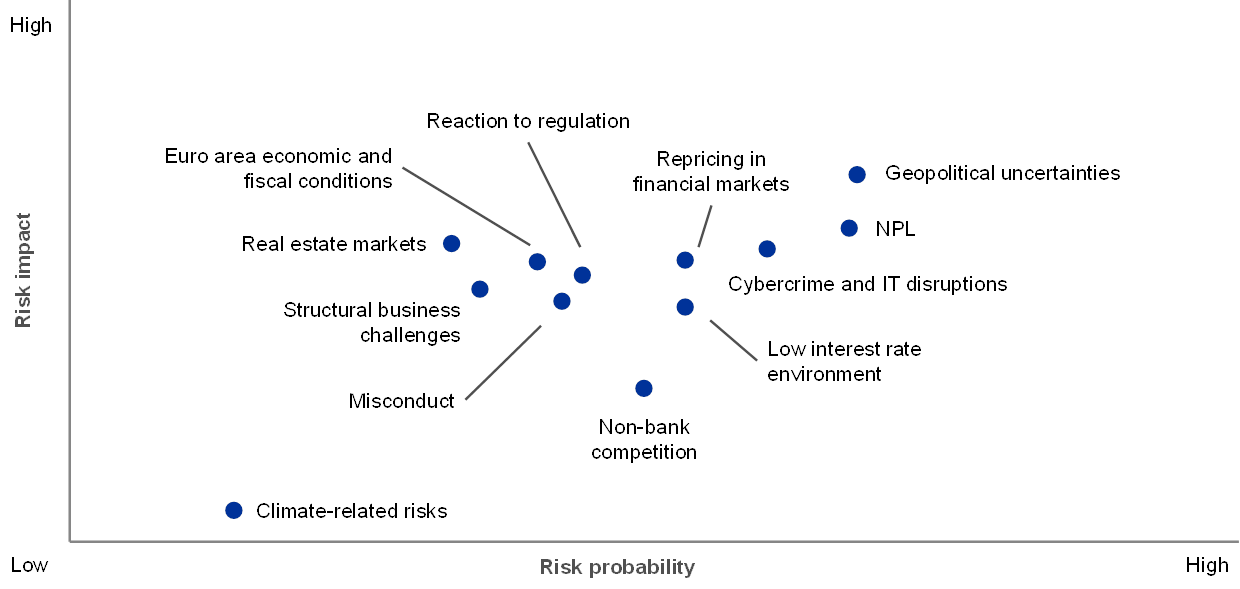

Geopolitical uncertainties and the risk of repricing in financial markets, on the other hand, have escalated since 2017. Moreover, ever-increasing digitalisation is exacerbating the risks related to banks’ (often legacy) IT systems and cyber security (see Chart 1).

Chart 1

SSM Risk Map for 2019

Sources: ECB and national supervisory authorities.

Notes: The probability and impact of risk drivers are based on the outcome of a qualitative assessment. The assessment identifies the key developments that might materialise and adversely affect the euro area banking system in the short to medium term (two to three years).

Geopolitical uncertainties are a growing risk

The reporting period saw an escalation of geopolitical uncertainties regarding, among other things, the political situation in some euro area countries, rising trade protectionism and adverse developments in certain emerging market economies, all of which could have negative repercussions on financial markets and the economic outlook for the euro area. With regard to Brexit, it remains uncertain whether a withdrawal agreement will be in place on the date of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union and, therefore, whether a transition period will apply, meaning that banks and supervisors need to be prepared for all possible scenarios.

Banks significantly reduced their legacy NPLs

Despite a significant improvement in asset quality in recent years, high levels of NPLs remain a concern for a significant number of euro area banks. Owing to the ongoing implementation of NPL reduction strategies, those banks have already made significant progress in reducing their volumes of legacy NPLs, with the NPL ratio of significant institutions (SIs) falling from 8% in 2014 to 4.2% in the third quarter of 2018. Nevertheless, the current aggregate level of NPLs remains high, and further efforts are needed to ensure that the issue of NPLs in the euro area is adequately addressed.

Potential future build-up of NPLs should be closely monitored

In addition, banks’ continued search for yield could increase the potential for a future build-up of NPLs. Euro area banks reported an easing of credit standards throughout 2018, although this development slowed down in the last quarter of 2018.[1] Moreover, they seem to be turning to more risky sectors and accepting lower levels of protection. Leveraged loan issuance in the euro area reached new heights in 2017, with “covenant-lite” loans making up a record high proportion of the volumes issued.

Ever-increasing digitalisation is driving up IT and cybercrime-related risks

Cybercrime and IT disruptions are a growing challenge for banks amid the trend towards digitalisation. They are under mounting pressure to invest in and modernise their core IT infrastructures to boost efficiency, enhance the quality of customers’ experience and compete with fintech/big tech companies. Moreover, they are faced with an increasing number of cyberthreats.

Risk of repricing in financial markets has increased

The global search for yield, ample liquidity and compressed risk premia have heightened the risk of a sudden repricing in financial markets, which is also being exacerbated by the high level of geopolitical uncertainty. On average, the sustainability of public sector debt has improved in the euro area, supported by the positive cyclical momentum. However, stock imbalances are still elevated in several countries, leaving them vulnerable to a potential repricing of sovereign risk.

Banks’ profitability improved but is still subdued

The positive economic developments during the reporting period supported banks’ profitability levels, although they remain subdued. The long period of low interest rates, while supporting the economy, has put pressure on banks’ interest margins. On aggregate, SIs forecast a pick-up in net interest income in 2019 and 2020. However, many expect their profits to remain low in terms of return on equity in the coming years.

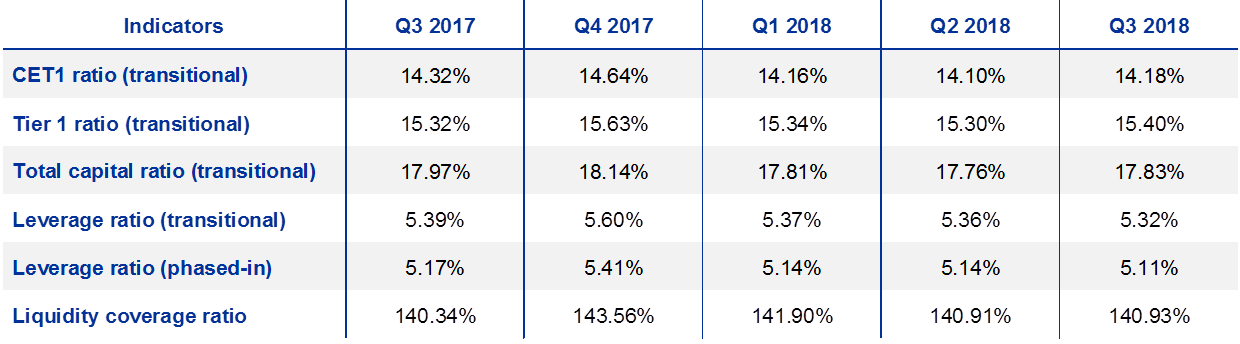

Euro area SIs entered the 2018 stress test with higher capital ratios

The results of the 2018 EU-wide stress test, coordinated by the European Banking Authority (EBA), show that the 33 largest banks directly supervised by the ECB have further enhanced their resilience over the past two years. Owing to their efforts in dealing with legacy assets and consistently building up capital, they entered the stress test with an average capital base that was much stronger, with Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) standing at 13.7%, up from 12.2% prior to the 2016 stress test.

A more severe scenario and stricter methodology led to higher capital depletion in the adverse scenario

For the 33 largest banks under the direct supervision of the ECB, the adverse scenario led to an aggregate CET1 depletion of 3.8 percentage points on a fully loaded basis[2], which is 0.5 percentage point higher than in the 2016 stress test. This includes a 0.3 percentage point impact from the first-time application of IFRS 9, which came into force on 1 January 2018. It also reflects the use of a more severe macroeconomic scenario and more risk-sensitive methodology than in 2016. All of these factors offset the positive effects of the improvement in asset quality following the successful reduction of NPLs.

Stress test results show that banks are generally more resilient, but vulnerabilities remain

Despite the higher capital depletion, the aggregate post-stress capital ratio was higher than in the 2016 adverse scenario, standing at 9.9% compared with 8.8%. This confirms that the resilience of the participating banks to macroeconomic shocks has improved. However, the exercise also exposed vulnerabilities in some individual banks, which supervisors will follow up on in 2019.

Stress test results show that an additional 54 banks not included in the EBA sample are now better capitalised

In addition to the 33 banks in the EBA sample, the ECB conducted its own stress test on another 54 banks which it directly supervises and which were not included in the EBA sample. The results of the stress test show that these 54 banks have also become better capitalised, increasing their ability to absorb financial shocks. Thanks to the continuous build-up of capital in recent years, they entered the stress test with a higher average CET1 ratio of 16.9%, up from 14.7% in 2016. They exited the test with a higher average final CET1 ratio of 11.8%, compared with 8.5% in 2016.[3]

Box 1

The 2018 stress tests

Overall set-up of the 2018 stress test and involvement of the ECB

As in previous years, the ECB was involved in both the preparation and execution of the 2018 EU-wide stress test, which was coordinated by the EBA. As part of the preparatory work, the ECB took part in designing the stress test methodology as well as the baseline and adverse scenarios. The adverse scenario was developed together with the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) and the EBA, and in close cooperation with the NCAs. Benefiting from a fruitful collaboration with experts from the EBA and NCAs, the ECB also produced the official credit risk benchmarks for the stress test. Banks are expected to apply these credit risk benchmarks to portfolios where no appropriate credit risk models are available.

Following the launch of the EU-wide stress test on 31 January 2018, the ECB, together with the NCAs, carried out the quality assurance process for the banks under its direct supervision. The key objective was to ensure that banks were correctly applying the common methodology developed by the EBA. Of the 48 banks covered by the EU-wide stress test, 33 are directly supervised by ECB Banking Supervision and account for 70% of euro area banking assets. The EBA published the individual results for all 48 participant banks, along with detailed balance sheet and exposure data as at year-end 2017, on Friday, 2 November 2018.[4]

In addition, the ECB conducted its own stress test on 54 banks that are under its direct supervision, but were not included in the EBA sample. Earlier in 2018, it had also stress tested the four Greek banks that it directly supervises. While this stress test used the same methodology, scenarios and quality assurance approach as the EBA stress test, it was brought forward in order to complete the exercise before the end of the European Stability Mechanism’s third economic adjustment programme for Greece.

Scenarios

The adverse scenario for the 2018 stress test was based on a consistent set of macro-financial shocks that could materialise in a crisis, including a contraction of 2.4% in GDP, a 17% fall in real estate prices and a sudden 31% drop in equity prices across the euro area as a whole. It reflected the main systemic risks identified at the launch of the exercise, namely (i) abrupt and sizeable repricing of risk premia in global financial markets, (ii) an adverse feedback loop between weak bank profitability and low nominal GDP growth, (iii) concerns about the sustainability of public and private debt, and (iv) liquidity risks in the non-bank financial sector with potential spillover effects on the broader financial system.

Key drivers of the 2018 stress test results

One key driver of the capital depletion in the adverse macroeconomic scenario were credit impairments, which were largely attributable to the fact that the macroeconomic scenario was more severe than in the 2016 stress test, although NPL stocks played a less prominent role than in 2016 owing to the improved quality of assets on banks’ balance sheets. A second key driver was a funding spread shock that was partly offset by the positive effect of higher long-term interest rates. A third key driver was the impact of market price and liquidity shocks on fair value portfolios. The impact of the full revaluation of these portfolios was strongest for global systemically important banks (G-SIBs). However, these banks were largely able to compensate for the losses with high client revenues. The stress impact of the scenario on liquidity reserves and model uncertainty also affected G-SIBs more than other entities. Another key driver was significant stress on net fee and commission income.

Stress test integration into regular supervisory work

Both the qualitative results (i.e. the quality and timeliness of banks’ submissions) and the quantitative results (i.e. capital depletion and banks’ resilience to adverse market conditions) of the stress test have served as input to the annual Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP). In the context of the SREP, the stress test results have also been taken into account when determining the supervisory capital demand.

SSM supervisory priorities

The SSM supervisory priorities, which set out focus areas for supervision in a given year, are discussed and approved by the Supervisory Board of the ECB. They build on an assessment of the key risks faced by supervised banks, taking into account the latest developments in the economic, regulatory and supervisory environment. The priorities, which are reviewed on an annual basis, are an essential tool for coordinating supervisory actions across banks in an appropriately harmonised, proportionate and efficient way, thereby contributing to a level playing field and a stronger supervisory impact (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Supervisory priorities 2019

Source: ECB.

1 Non-performing loans

2 Targeted Review of Internal Models

3 Internal Capital and Liquidity Adequacy Assessment Processes

4 In 2018 the EU-wide stress test was performed.

5 Planned activities include an OSI campaign on valuation risk and a horizontal analysis consisting of a data collection exercise to equip the JSTs with more granular information on complex assets assessed at fair value, such as those classified as level 2 and level 3.

General performance of significant banks in 2018

After improving in 2017, the profitability of euro area banks remained more or less stable in 2018

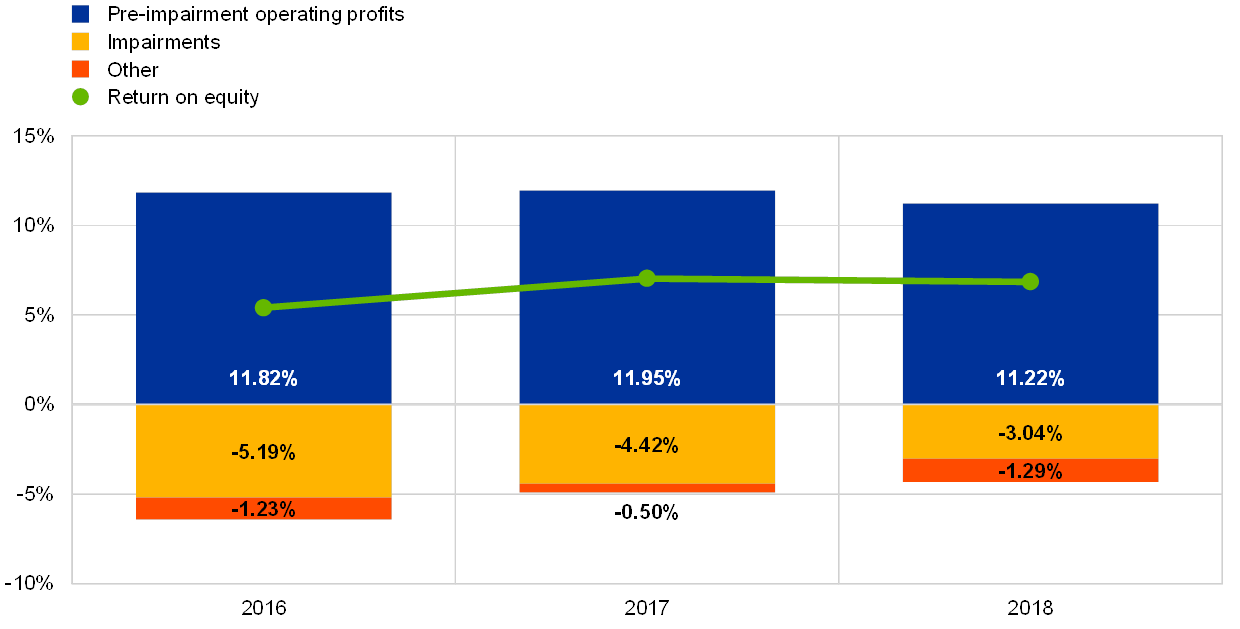

The profitability of euro area banks remained more or less stable in 2018, after improving in 2017. The annualised return on equity for SIs changed only slightly, averaging at 6.9%, compared with 7.0% in 2017 and 5.4% in 2016. However, this overall stable level of profitability masks considerable differences across banks. Moreover, many publicly listed banks are still trading with price-to-book ratios below one, indicating that further improvements are needed to meet investors’ expectations.

In 2018 two main factors affected banks’ aggregate earnings. Having increased in 2017, pre-impairment operating profits fell considerably, by 7.1%, over the first nine months of 2018. This decline was largely offset by a sharp decrease in impairments (-31.8% compared with 2017).

The drop in pre-impairment operating profits was driven mainly by lower net trading income (-50%)[5], compared with the first three quarters of 2017. By contrast, net fee and commission income continued to improve and stood 1.4% above the value recorded in the first three quarters of 2017, while over the same time period, net interest income remained broadly stable (-0.1%).

Chart 2

Stable return on equity (annualised figures) in 2018: lower pre-impairment operating profits offset by a decline in impairments

(All items are displayed as percentages of equity)

Source: ECB Supervisory Banking Statistics.

Note: Data for all years are shown as second quarter cumulated figures, in annualised terms.

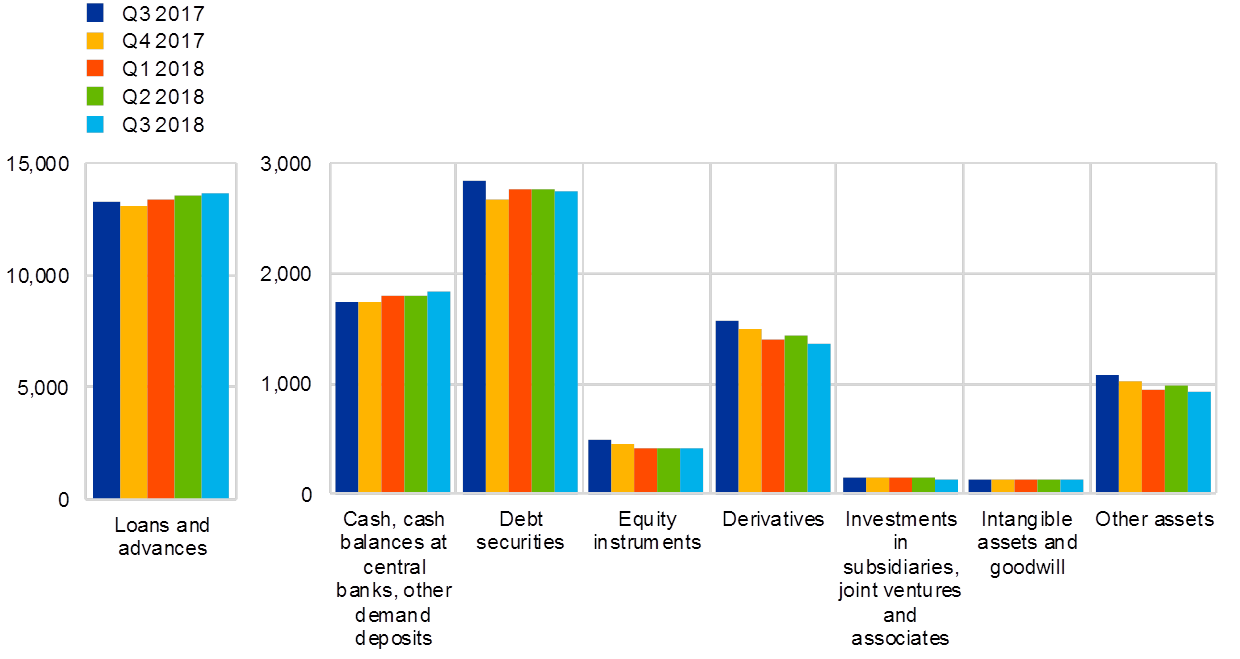

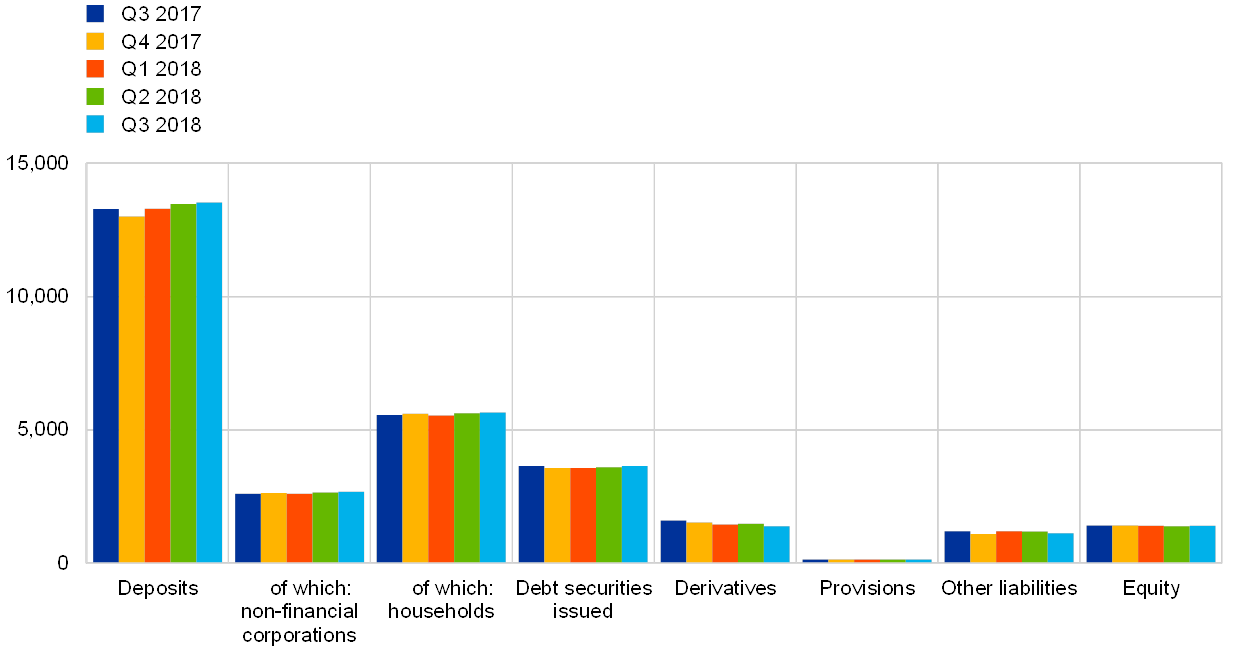

The stable evolution of net interest income masks two underlying trends, as growing loan volumes were offset by lower interest margins. Loan volumes increased by 2.8% between the third quarter of 2017 and the third quarter of 2018, with the financial institutions segment (loans to credit institutions: +3.7%; loans to other financial corporations: +12.1%) and the non-financial corporations segment (+3.3%) displaying the most dynamic growth. Over the first three quarters of 2018, net interest income improved for roughly half of SIs and declined for the remaining half.

Operating expenses increased by 2.0% in the first three quarters of 2018 with respect to the same period in 2017, despite the restructuring measures recently taken by several euro area banks.

1.2 Work on non-performing loans (NPLs)

1.2.1 The situation across Europe

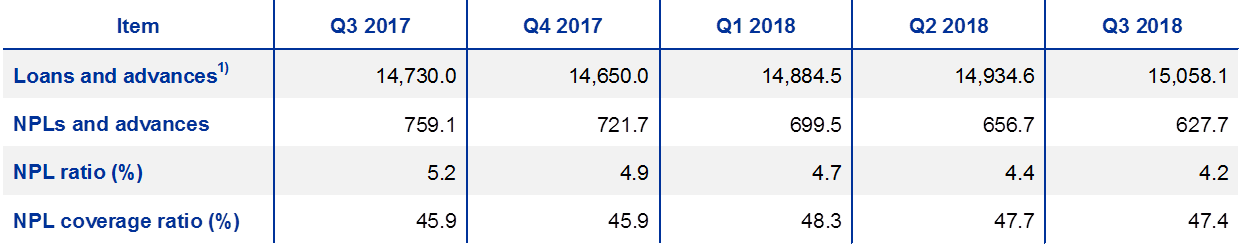

NPL stocks have declined since 2015 …

The volume of NPLs on SIs’ balance sheets stood at €628 billion in the third quarter of 2018, down from €1 trillion in early 2015. Between the third quarter of 2017 and the third quarter of 2018, it decreased by €131 billion, and the gross NPL ratio dropped by 1 percentage point, to 4.2%. The decline in NPLs has accelerated over the past two years and has been particularly rapid in countries with high NPL ratios.

Nevertheless, the aggregate level of NPLs in the European banking sector remains elevated by international standards, and the clean-up of balance sheets will take more time.

… but the aggregate level remains high by international standards

Work on NPLs was one of ECB Banking Supervision’s most important supervisory priorities in 2018 and will continue to be an area of focus in 2019, building on the achievements thus far by engaging with affected institutions to define bank-specific supervisory expectations within a harmonised framework. The aim is to ensure continued progress in reducing legacy risks and to achieve consistent coverage of both the stock of NPLs and new NPLs over the medium term.

With regard to NPL statistics, the ECB publishes its Supervisory Banking Statistics[6] on a quarterly basis, including data on asset quality for SIs. Table 1 shows the decrease in NPL levels between 2017 and 2018.

Table 1

NPLs and advances – amounts and ratios by reference period

(EUR billions; percentages)

Source: ECB.

Note: The table covers SIs at the highest level of consolidation for which common reporting on capital adequacy (COREP) and financial reporting (FINREP) are available. Specifically, there were 114 SIs in the third quarter of 2017, 111 in the fourth quarter of 2017 and 109 in the first, second and third quarters of 2018. The number of entities per reference period reflects changes resulting from amendments to the list of SIs following assessments by ECB Banking Supervision, which generally occur on an annual basis, and mergers and acquisitions.

1) Loans and advances in the asset quality tables are displayed at gross carrying amount. In line with FINREP: i) held for trading exposures are excluded, and ii) cash balances at central banks and other demand deposits are included. In accordance with the EBA’s definition, NPLs are loans and advances other than held for trading that satisfy either or both of the following criteria: (a) material loans which are more than 90 days past due; (b) the debtor is assessed as unlikely to pay its credit obligations in full without realisation of collateral, regardless of the existence of any past-due amount or of the number of days past due. The coverage ratio is the ratio between accumulated impairments on loans and advances and the stock of NPLs.

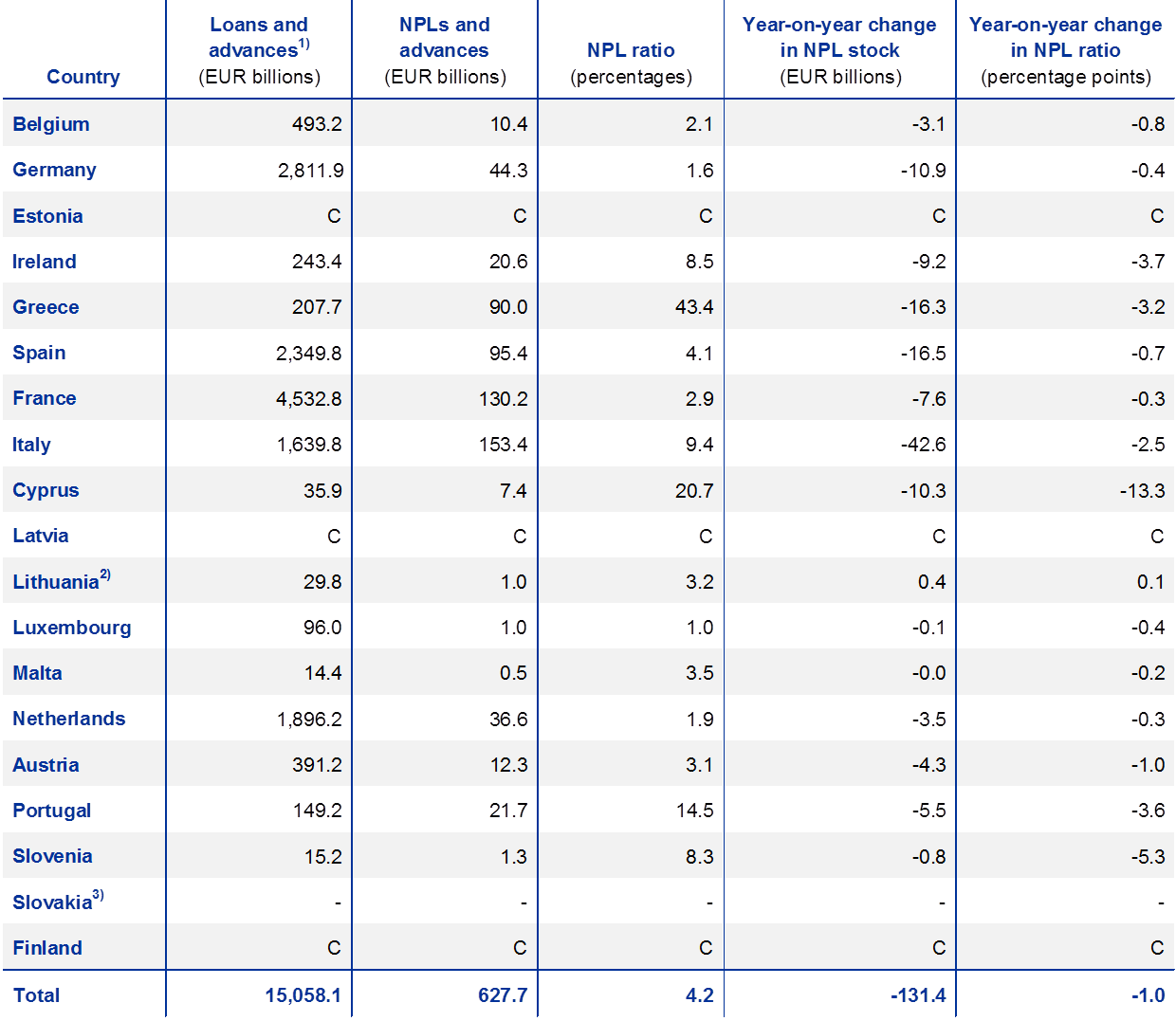

NPL ratios vary markedly across the euro area

Across the euro area, NPL ratios continue to differ significantly from country to country, as shown in Table 2. Greek, Cypriot and Portuguese SIs have the highest NPL ratios (with country-weighted averages standing at 43.4%, 20.7% and 14.5% respectively in the third quarter of 2018). Looking at the trend, the NPL ratio decreased significantly year-on-year for SIs in Cyprus (-13.3 percentage points), Slovenia (-5.3 percentage points), Ireland (-3.7 percentage points), Portugal (-3.6 percentage points), Greece (-3.2 percentage points) and Italy (-2.5 percentage points). In the third quarter of 2018, the stock of NPLs was largest in the case of Italian SIs (€153 billion), followed by French SIs (€130 billion), Spanish SIs (€95 billion) and Greek SIs (€90 billion).

Table 2

NPLs and advances – amounts and ratios by country (reference period: third quarter of 2018)

(EUR billions; percentages; percentage points)

Source: ECB.

Notes: SIs at the highest level of consolidation for which common reporting (COREP) and financial reporting (FINREP) are available.

C denotes that the value is not included for confidentiality reasons.

1) Loans and advances in the asset quality tables are displayed at gross carrying amount. In line with FINREP: i) held for trading exposures are excluded, and ii) cash balances at central banks and other demand deposits are included.

2) The increase in the NPL ratio in LT was driven by a change in the approach to consolidation regarding one SI.

3) There are no SIs at the highest level of consolidation in Slovakia.

1.2.2 The role of ECB Banking Supervision in the comprehensive strategy to resolve NPL issues in the EU

ECB Banking Supervision has developed a supervisory framework for NPLs

Addressing the risks related to high stocks of NPLs is important for the economy as a whole, as NPLs weigh on banks’ profitability and absorb valuable resources, restricting their ability to grant new loans. Problems in the banking sector can quickly spread to other parts of the economy to the detriment of the outlook for jobs and growth. The ECB thus recommends that banks do more to tackle their stocks of NPLs, in line with its mandate to help ensure the safety and soundness of the European banking system.

ECB Banking Supervision has developed a supervisory framework for NPLs. This includes three strategic elements, which either directly address legacy NPLs or aim to prevent the build-up of new NPLs in the future:

- NPL guidance to all SIs, outlining qualitative supervisory expectations with regard to managing and reducing NPLs;

- A framework to address NPL stocks as part of the supervisory dialogue, comprising: (i) an assessment of the banks’ own NPL reduction strategies, and (ii) bank-specific supervisory expectations with a view to ensuring adequate provisioning of legacy NPLs;

- Addendum to the NPL guidance, outlining quantitative supervisory expectations to foster timely provisioning practices for new NPLs.

NPL task force concluded its work in 2018

The framework was developed by a dedicated task force, which comprised representatives from NCAs and the ECB. The EBA was also represented in the group as an observer. A high-level group on NPLs – chaired by Sharon Donnery (Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland) – steered the task force’s work. Between 2015 and 2018 the high-level group met 16 times to discuss proposals for developing and implementing a supervisory framework for NPLs. The Chair reported back to the Supervisory Board 14 times and to the Governing Council five times. Having delivered on its mandate, the task force was disbanded in late 2018 and the application of the NPL supervisory framework successfully handed over to ECB Banking Supervision line functions.

A comprehensive strategy to address NPL stocks requires action from all stakeholders, including the EU and national public authorities

However, solving the challenge of NPLs goes far beyond supervisory action. National authorities and European institutions need to join forces to resolve the issue. This was also one of the main findings of the ECB’s NPL stocktake on national practices, the latest version of which was published in June 2017. Furthermore, it was recognised by the Economic and Financial Affairs Council in July 2017, when finance ministers agreed on an Action plan to tackle non-performing loans in Europe. The plan sets out the need for action in three areas: banking supervision, reforms of insolvency and debt recovery frameworks, and the development of secondary markets. In November 2018 the Commission published the Third Progress Report on the action plan, which stated that substantial progress had been made with its implementation. ECB Banking Supervision has been actively contributing to numerous NPL initiatives in the three aforementioned areas, including those outlined in the action plan, in close collaboration with the stakeholders in charge of the initiatives.

In this context, ECB Banking Supervision closely coordinated with the relevant European institutions, such as the European Commission, on the need to ensure the complementary nature of (i) the proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 as regards minimum loss coverage for non-performing exposures, and (ii) the Addendum to the ECB guidance to banks on NPLs.

Furthermore, ECB Banking Supervision supported the EBA in issuing general guidelines on the management of non-performing and forborne exposures, and guidelines on the disclosure of non-performing and forborne exposures. These guidelines are to be applied by all credit institutions across the EU. With regard to less significant institutions (LSIs), they are to apply the guidelines in a proportionate manner, as set out in the guidelines. In addition, the ECB, in close cooperation with the EBA and the Single Resolution Board (SRB), assisted the European Commission services in the preparation of a technical blueprint for setting up national asset management companies, which was published in March 2018.

Finally, ECB Banking Supervision continued to work alongside the EBA to enhance underwriting standards for new loans. It also participated in the ESRB working group that produced the report on macroprudential approaches to non-performing loans, which focuses on the role macroprudential policy can play in preventing system-wide increases in NPLs.

1.2.3 Key elements of ECB Banking Supervision’s supervisory approach to NPLs

Banks’ NPL reduction strategies – progress and assessment

In March 2017 the ECB published its guidance to banks on NPLs. As a follow-up to this guidance, SIs with higher levels of NPLs and foreclosed assets were asked to submit their NPL and foreclosed asset reduction strategies to ECB Banking Supervision. In this regard, the NPL guidance forms the basis for the ongoing supervisory dialogue with individual banks. It is the banks themselves that are responsible for implementing adequate NPL strategies and managing their NPL portfolios using a range of strategic options, such as NPL workout, servicing, portfolio sales, etc.

Such NPL strategies should contain targets for reducing NPLs at the portfolio level over a three-year horizon. These targets are set by the banks themselves and submitted to the JSTs. Chapter 2 of the NPL guidance outlines best practices for formulating NPL reduction strategies and provides a list of tools for their implementation, including forbearance, active portfolio reductions, change of exposure type and legal options. It also highlights that banks should ensure that their NPL strategies include “not just a single strategic option but rather combinations of strategies/options to best achieve their objectives over the short, medium and long term”. The ideal combination of such tools depends on the characteristics of each bank’s portfolio and on the market and legal environment in which it is operating. It is important to note that each bank’s management should use its own discretion when choosing the combination of tools on the basis of a thorough assessment. The ECB has not expressed any preference for certain NPL reduction tools over others.

The role of the Joint Supervisory Teams (JSTs) is to review, challenge and monitor the banks’ progress against their NPL reduction targets. This role is fully embedded in their normal supervisory work and is an integral part of the SREP. The JSTs’ assessment of the strategies focuses on three overarching elements: (i) level of ambition, (ii) the credibility of the strategy, and (iii) governance aspects. The assessments are based on very granular examinations of the banks’ portfolios of gross non-performing exposures and foreclosed assets, which can be bundled under the term “non-performing assets”).

Banks with higher levels of NPLs are required to report specific NPL data to the JSTs on a quarterly basis, detailing the underlying drivers of their NPL reduction. The JSTs use these quarterly reports to monitor the banks’ progress and measure it against the reduction targets in their strategies, on both an overall and portfolio level basis. In addition, they monitor the banks’ progress against targets both gross and net of provisions to ensure that the analysis follows a holistic approach. As part of their regular interaction with the JSTs, banks are expected to prepare and submit an implementation report twice a year.

The objective of the implementation report is to ascertain how the banks are performing against their NPL strategies, from both a quantitative and qualitative perspective. Quantitative progress can be measured on the basis of the quarterly NPL data and broken down to identify specific drivers of the reduction in NPLs, such as cash repayments, sales, write-offs, etc. Accordingly, a bank should focus not only on analysing its overall reductions but also on pinpointing drivers at the portfolio level and the reasons behind the associated over or underperformance. The rationale is that a bank’s track record and future capabilities in reducing NPLs are strongly linked.

To document these quantitative aspects, it is recommended that banks carry out a targeted analysis and review of specific problematic asset classes or portfolios, including their impact on capital at the portfolio level. They should also ensure that their NPL strategies are constantly updated, taking into account all such inputs and analyses to ensure that they are credible, fit for purpose and actionable.

The qualitative aspects of a bank’s progress are also very important. Its NPL strategy should therefore also include a well-defined operational plan as a basis for the qualitative milestones, actions and objectives of the strategy. When reviewing its qualitative progress, it should proactively identify any potential roadblocks to the strategy’s successful implementation. In this regard, the various drivers of reductions in NPLs require different things. The curing of loans, for instance, requires a sound operational framework, adequate resources and a comprehensive forbearance framework, while the sale of portfolios requires good quality data, a sophisticated IT infrastructure, experienced management and suitable financial advisors. On a bank-by-bank basis, the JSTs review the qualitative aspects of the banks’ strategies and provide them with feedback on any deficiencies identified.

The NPL guidance focuses heavily on the importance of dedicated NPL workout units, clear policies and procedures, and a well-defined suite of forbearance products. It also emphasises the need for management bodies to be heavily involved and engaged with regard to the issue of NPLs. Banks therefore need to review their internal governance structures and operational arrangements in terms of the management of NPLs – management bodies should, for example, take full ownership of the problem.

A greater focus on curing, workout and restructuring may help to foster more prudent credit risk practices, which could, over time, help banks to apply more risk-appropriate standards and governance to their lending activities.

Over the past few years, banks have generally made good progress with their NPL strategies, as evidenced by the significant decline in NPL stocks across many European countries and banks. This notwithstanding, NPL stocks remain at a high level. For this reason, the JSTs are continuing to engage with the banks and challenge them when necessary to ensure that they make further progress. If individual banks do not meet their own targets, they are expected to implement sufficient and appropriate remediation action in a timely manner.

Banks are using a variety of drivers to reduce NPL stocks, across both institutions and countries. These include forbearance and associated cash repayments, portfolio sales, write-offs and foreclosures. Certain countries favour some drivers over others because of individual circumstances. However, there also appears to be a variety of approaches, even within individual countries, depending on the banks’ individual circumstances.

The NPL strategy process is now an integral part of the high-NPL banks’ processes and ECB Banking Supervision’s supervisory processes. Accordingly, work on this supervisory priority will be continued in 2019.

Bank-specific supervisory expectations for the provisioning of NPL stocks

Further steps in the supervisory approach to the stock of NPLs create a consistent framework for addressing the issue as part of the supervisory dialogue

On 11 July 2018 the ECB announced further steps in its supervisory approach to the stock of NPLs (i.e. exposures classified as non-performing according to the EBA’s definition of 31 March 2018). The approach creates a consistent framework for addressing the issue, as part of the supervisory dialogue, through bank-specific supervisory expectations aimed at achieving adequate provisioning of legacy NPLs, thereby contributing to the resilience of the euro area banking system as a whole.

Under this approach, ECB Banking Supervision has further engaged with each bank to define its supervisory expectations. This assessment was guided by individual banks’ current NPL ratios, their main financial features, their NPL reduction strategy (if available) and a benchmarking of comparable peers in order to ensure consistent treatment. It also took into account the most recent data and their capacity to absorb additional provisions.

All SIs under the direct supervision of the ECB have been assessed with the aim of setting bank-specific expectations to ensure continued progress in reducing legacy risks in individual banks and to achieve the same coverage of the stock and flow of NPLs over the medium term.

Finalisation of the addendum to the NPL guidance

Publication of the addendum followed an extensive public dialogue with all relevant stakeholders

In early 2018 the ECB finalised its addendum to the ECB Guidance to banks on non-performing loans. This was preceded by a public consultation, which ran from 4 October to 8 December 2017. On 15 March 2018 the ECB published the addendum together with detailed comments from the consultation and a feedback statement setting out the ECB’s response to those comments.

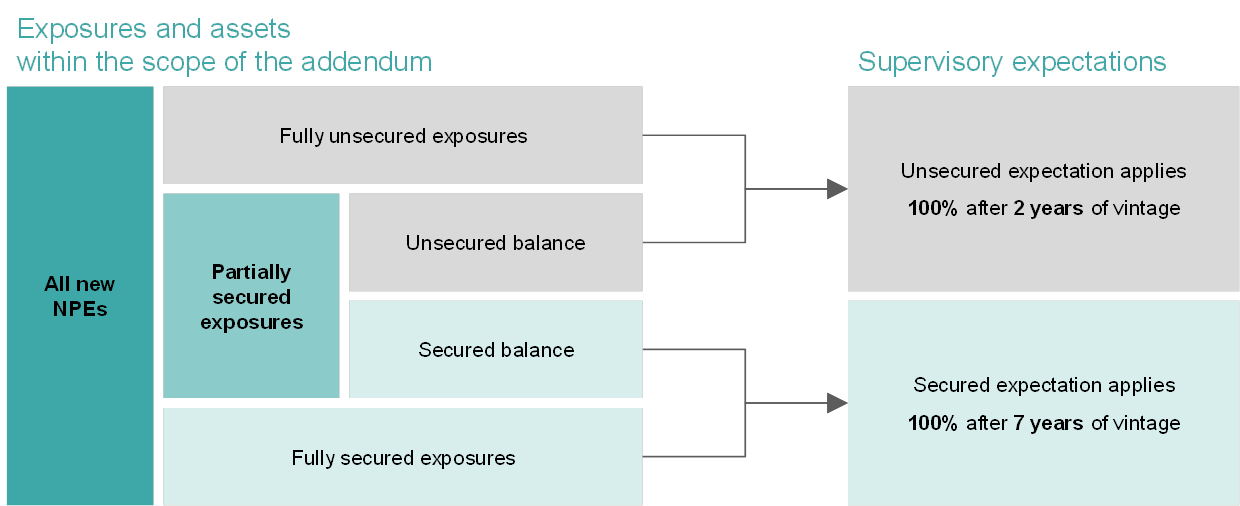

The addendum supplements the qualitative NPL guidance, published on 20 March 2017, and specifies the ECB’s supervisory expectations for prudent levels of provisions for new NPLs. It is non-binding and serves as a basis for the supervisory dialogue between SIs and ECB Banking Supervision. It addresses loans classified as NPLs after 1 April 2018, in line with the EBA’s definition.

The background to the addendum is that, in line with the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV), supervisors have to assess and address institution-specific risks which are not already covered, or which are insufficiently covered, by the mandatory prudential requirements in the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) (often referred to as “the Pillar 1 rules”). In particular, the existing prudential framework requires supervisors to assess and decide whether banks’ provisions are adequate and timely from a prudential perspective. The addendum lays out what ECB Banking Supervision expects in this regard and thus clarifies the starting point for the supervisory dialogue. As with other supervisory expectations, the addendum is complementary to any binding legislation; this includes the proposal for a Regulation amending the CRR as regards minimum loss coverage for non-performing exposures. The ECB therefore cooperated closely on the addendum with the relevant European institutions, such as the European Commission.

Figure 2

Overview of quantitative supervisory expectations outlined in the NPL addendum

Source: ECB.

The supervisory expectations outlined in the addendum take into account the extent to which NPLs are secured. For fully unsecured exposures and unsecured parts of partially secured exposures, it is expected that 100% coverage is achieved within two years of the NPL classification. For fully secured exposures and secured parts of partially secured exposures, it is expected that 100% coverage is achieved within seven years of the NPL classification, following a gradual path. The expectations for secured exposures adhere to the prudential principle that credit risk protection must be enforceable in a timely manner.

The addendum is to be implemented through the supervisory dialogue with each bank

The practical implementation of the addendum is to form part of the supervisory dialogue, in which the JSTs discuss with each bank divergences from the prudential provisioning expectations set out in the addendum. Thereafter, and taking into account the bank’s specific circumstances, ECB Banking Supervision will decide, on a case-by-case basis, whether supervisory measures are appropriate and if so, which. The results of this dialogue will be incorporated, for the first time, in the 2021 SREP. Banks should use the time to prepare themselves and also to review their credit underwriting policies and criteria to reduce the emergence of new NPLs, in particular during the current benign economic conditions.

1.3 Further development of the SREP methodology

1.3.1 ICAAP/ILAAP to play a greater role in supervisory assessment

In the future, the ICAAP and ILAAP are expected to play an even bigger role in the SREP, incentivising banks to keep improving their internal processes

Financial shocks to the banking sector are often amplified or even caused by the inadequate amount and quality of the capital and liquidity held by banks. Two core processes, the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP) and the Internal Liquidity Adequacy Assessment Process (ILAAP), are essential to strengthening institutions’ resilience. The requirements for their ICAAPs and ILAAPs are stipulated in the CRD IV.

Both the ICAAP and ILAAP aim to encourage institutions to measure and manage their capital and liquidity risks in a structured way, using institution-specific approaches. They are not simply about producing a report for the benefit of supervisors: they are comprehensive and valuable bank-internal processes for identifying, assessing and effectively managing and covering capital and liquidity risk at all times. Banks are responsible for implementing the ICAAP and ILAAP in a proportionate manner, i.e. they need to be commensurate with, among other things, the institution’s business model, size, complexity and riskiness, as well as with market expectations.

As stated in the SSM supervisory priorities, the ICAAP and ILAAP are key instruments for institutions in managing their capital and liquidity adequacy. For that reason, they warrant particular attention from supervisors. As part of the SREP, the quality and the results of ICAAPs and ILAAPs are taken into account when establishing capital, liquidity and qualitative measures. Good ICAAPs and ILAAPs reduce uncertainty for both institutions and supervisors regarding the actual risks an institution is exposed to. In addition, they reassure supervisors to a greater extent of the institution’s ability to ensure its capital and liquidity adequacy, and thus remain viable.

In the future, the ICAAP and ILAAP are to play an even bigger role in the SREP, incentivising banks to keep improving their internal processes. Among other things, both the qualitative and quantitative aspects of the ICAAP will play an enhanced role in the determination of Pillar 2 own funds requirements on a risk-by-risk basis.

1.3.2 Finalisation of the guides for banks on their capital and liquidity management

Banks are encouraged to use the guides to close any gaps and remedy deficiencies in their capital and liquidity management as soon as possible

In its recent SREP assessments, ECB Banking Supervision came to the conclusion that there were serious shortcomings in more than half of SIs’ ICAAPs and more than one-third of their ILAAPs, as reflected in overall verdicts of either “inadequate” or “weak”. Such ICAAPs and ILAAPs do not provide a solid basis for either the prudent management of capital and liquidity or the determination of additional own funds requirements. Thus, there is a need for institutions to (further) improve their ICAAPs and ILAAPs.

In November 2018 ECB Banking Supervision published guides regarding institutions’ ICAAPs and ILAAPs. These guides will play an important role in facilitating the necessary improvements. They are a major milestone in the ECB’s attempt to improve banks’ approaches to capital and liquidity management, which began with the publication of its supervisory expectations regarding ICAAPs and ILAAPs in January 2016. As a follow-up, it then launched a multi-year plan for ICAAPs and ILAAPs in early 2017, the aim being to set out more detailed expectations and communicate to institutions early on what direction they would be expected to take. The 2016 expectations were used as a basis for the guides and underwent three rounds of enhancements, taking into consideration around 800 comments that were collected by means of two public consultations. Nevertheless, the general direction of the expectations remained unchanged throughout that process.

Overview of the seven ICAAP and ILAAP principles

The seven ICAAP and ILAAP principles refer to:

- Governance: management bodies are expected to take full responsibility for ICAAPs and ILAAPs.

- Integration: ICAAPs and ILAAPs should form integral parts of the overall management framework, including business decision-making. Both processes should be consistent within themselves, between each other and with other strategic processes.

- Quantitative framework: it is expected that capital and liquidity adequacy are ensured from two different perspectives in terms of the institution’s continued viability – a “normative” perspective, which reflects external requirements and constraints, and an “economic” perspective, which should reflect the undisguised economic situation.

- Risk identification: all material risks are expected to be identified and managed.

- Internal capital/liquidity definitions: from the economic perspective, the capital and liquidity buffers are expected to be of a high quality and clearly defined so that economic losses can be absorbed when they occur.

- Risk quantification methodologies: risks are expected to be assessed and quantified in a conservative manner, using own risk quantification methodologies that have been thoroughly validated.

- Stress testing: the ECB expects banks to implement sound and comprehensive stress-testing frameworks which ensure that they can survive by themselves during plausible, yet very severe and prolonged periods of adverse circumstances.

The expectations in the guides are now far more comprehensive, and the ECB started to apply them in January 2019. However, the guides are not intended to provide complete guidance on all aspects relevant to sound ICAAPs and ILAAPs. Instead, they follow a principles-based approach with a focus on selected key aspects from a supervisory perspective. ECB Banking Supervision thus stresses that, in the first place, ICAAPs and ILAAPs are internal processes that should be tailored to each institution. The implementation of an ICAAP and ILAAP appropriate for its particular circumstances therefore remains the responsibility of each individual institution. The guides help banks do this by setting out the ICAAP and ILAAP expectations in the form of seven principles and by providing a number of charts and examples as illustrations.

As a key part of the SREP, but also in other activities such as on-site inspections (OSIs), supervisors will assess on a case-by-case basis whether institutions are meeting their responsibilities and managing their capital and liquidity in a way that is commensurate with their individual business activities, risk profile and other relevant circumstances. It is expected that the conclusions drawn from these assessments will have an ever greater influence on the SREP and its follow-up in terms of supervisory measures. If banks have good and sound ICAAPs/ILAAPs, this will be positively acknowledged in the SREP.

As sound, effective, comprehensive and forward-looking ICAAPs and ILAAPs are key instruments for ensuring their resilience, banks are encouraged to use the guides to close any gaps and remedy deficiencies in their capital and liquidity management as soon as possible. As the overall philosophy and direction of the ECB’s supervisory expectations have not changed since they were first published in January 2016, SIs are expected to do their utmost to take these expectations into account as soon as possible. The development of the guides was a multi-year process, and the ECB was very transparent about the gradual enhancement of its expectations. The short period between the publication of the guides in November 2018 and the start of their application in January 2019 does not justify inaction.

1.3.3 Steps taken to address IT risk

IT risk, including cyber risk, has been a focus area of ECB Banking Supervision from the outset and became one of the supervisory priorities for 2019.

As part of the ongoing operational risk supervision, the JSTs supervise IT risk. In 2018 they were provided with additional training on all relevant IT risk areas in order to advance their awareness and skills for ongoing supervisory activities, as well as for the annual SREP. On the basis of the EBA’s Guidelines on ICT Risk Assessment under the SREP, ECB Banking Supervision implemented a common and standardised IT risk assessment methodology. Using a comprehensive self-assessment questionnaire for banks, and the JSTs’ IT risk assessment results, an elaborate set of horizontal analyses was performed. This produced a wealth of findings that informed the JSTs’ supervisory activities, as well as thematic feedback on the overall state of IT risk management in SIs. In general, the analyses confirmed ECB Banking Supervision’s previous focus areas, namely IT security, third-party dependencies and third-party management, and IT operations.

OSIs focusing on IT risk continued in 2018, supplementing the ongoing supervision by the JSTs. Based on ECB Banking Supervision’s OSI methodology, the inspections investigated specific IT risk objectives at the request of the JSTs, in order to elaborate on and substantiate the IT risk assessments made by the JSTs and get a better idea of how SIs manage IT risks. In 2019 some IT risk OSIs will follow a campaign approach, where the same topic is inspected in several SIs on a comparable scale. This facilitates a more efficient preparation and execution of inspections, as well as a comparison of results.

As in previous years, all SIs from the 19 euro area countries were required to report significant cyber incidents as soon as they had been detected. This enables ECB Banking Supervision to identify and monitor trends in cyber incidents affecting SIs. It also allows it to react quickly in the event that a major incident affects one or more SIs.

In order to ensure a coordinated approach to IT and cyber risk, and to facilitate the sharing of knowledge and best practices, ECB Banking Supervision continued to liaise with all relevant stakeholders (NCAs, internal ECB stakeholders, payment systems and market infrastructure experts, other supervisors within and outside the EU, European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), etc.) through bilateral meetings and participation in international working groups.

1.4 Thematic reviews

Thematic review of business models and profitability drivers

In 2018 the multi-year thematic review on business models and profitability drivers was completed

In 2018 ECB Banking Supervision concluded its thematic review on business models and profitability drivers, and published a report on it. The thematic review was launched in 2016 with the aim of performing an in-depth, bank-by-bank analysis of SIs’ ability to mitigate weaknesses in their business models, monitoring the consequences of weak profitability and enriching horizontal analysis by integrating JSTs’ insights in a consistent manner across banks. The first two years of the review were dedicated to developing tools, collecting data and, for the JSTs, performing in-depth analyses.

At the beginning of 2018 the JSTs informed the SIs of the findings and main conclusions of the thematic review. As part of a dedicated supervisory dialogue, they discussed any shortcomings identified and challenged the SIs’ business plans. Follow-up letters summarised the findings and formalised the results of the supervisory dialogue. The findings fed into the business model assessment for the 2018 SREP cycle. In September 2018 ECB Banking Supervision published the overall messages from the thematic review on its website.

Euro area banks are still adjusting after the crisis, but the profitability situation differs widely across SIs

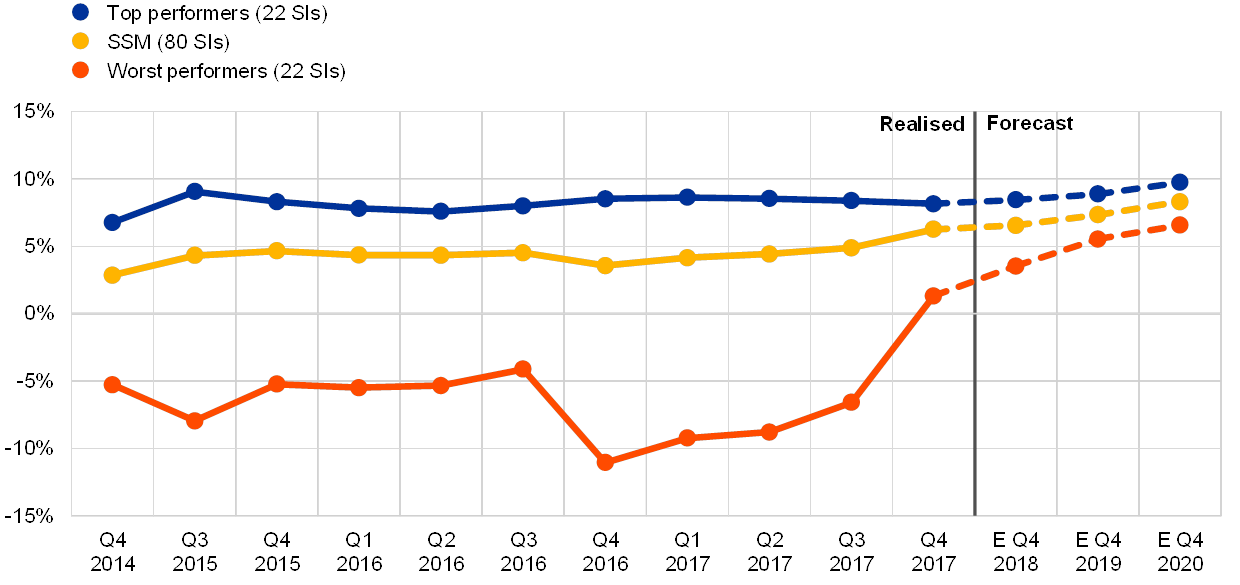

The review showed that even though the economic situation of banks in the euro area has generally improved, profitability and business models remain under pressure. Looking beyond the aggregate trends, the profitability situation differs widely across SIs, with some convergence to the mean projected by banks, as the worst performers expect significant improvements in their profitability (see Chart 3). Banks that outperformed their peers in previous years are geographically spread out, are of different sizes and have differing business models.

Chart 3

Three-year evolution of return on equity

(percentages)

Sources: FINREP and profitability forecast exercise.

Notes: All samples exclude subsidiaries of non-SSM banks. Top performers: 22 SIs with an average return on equity above 6% over the last three years. Worst performers: 22 SIs with a negative average return on equity over the last three years.

Strategic steering capabilities are an important factor for profitability

Increases in risk-taking by individual banks are closely monitored by their JSTs

The analysis confirmed that banks’ strategic steering capabilities[7] have a major influence on their profitability. JSTs also observed that many banks try to boost profitability by turning to activities that can entail more risk (most notably related to credit risk[8] or operational risk[9]). As there can be valid business reasons to turn to such activities, the individual recommendations do not necessarily challenge a given strategy, but rather focus on ensuring that strategic steering and risk management are improved by monitoring and containing the risk. JSTs have been involved in the identification and assessment of these issues and are following up on them as part of their regular monitoring of banks, using their full supervisory toolkit.

Thematic review of IFRS 9

IFRS 9 aims to ensure more adequate and timely provisioning

The new accounting standard for financial instruments (IFRS 9) entered into force in January 2018. It addresses the lessons learned from the financial crisis, namely, that provisions based on incurred loss models often resulted in loss recognition that could be described as “too little, too late”. IFRS 9 addresses this weakness by introducing an expected credit loss model that incorporates forward-looking information over a loan’s remaining lifetime. This, by its very nature, requires considerable effort to implement, with potential risks arising from the as-yet-unknown effectiveness of expected credit loss models in practice.

The results of the thematic review launched in 2016 to assess banks’ preparedness for IFRS 9 show room for improvement

The ECB therefore decided in 2016 to launch a thematic review on IFRS 9 as part of its supervisory priorities. The aim was to assess institutions’ preparedness and foster high quality and consistent implementation of the new standard. Institutions were divided into two batches, based on the progress they had made in implementing IFRS 9. The results of the thematic review for the first batch were published in a report on the ECB’s banking supervision website in 2017. The results for the second batch were published in an article in the Supervision Newsletter in 2018.

Overall, the thematic review helped increase awareness of the challenges banks are facing in implementing IFRS 9. At the same time, it highlighted that there is still room for improvement.

ECB Banking Supervision is closely monitoring the implementation of remedial actions by banks

It was recommended that institutions put in place remedial actions to rectify the shortcomings identified by the thematic review in 2017 and 2018. ECB Banking Supervision is currently closely monitoring their progress in implementing those actions. Among other things, the thematic review revealed a significant divergence in banks’ provisioning practices, which were subject to a follow-up by JSTs throughout 2018 and which will continue to be scrutinised in 2019. Another area of supervisory focus in 2018 was the impact of the first-time application of IFRS 9, including the change in the classification of exposures, the allocation of provisions and the migration of exposures between stages. In this regard, the ECB is looking into the banks’ accounting with a focus on regulatory capital and reporting.

In conducting its follow-up activities on the implementation of IFRS 9, ECB Banking Supervision is cooperating with the ESRB, EBA and ESMA on accounting-related topics in order to ensure a high-quality, consistent implementation of IFRS 9 and a high level of transparency for investors across the EU.[10]

A transition period will ease the potentially negative impact of IFRS 9 on banks’ regulatory capital

In addition, it is closely monitoring how banks are using the transitional arrangements for IFRS 9. These transitional arrangements were incorporated into the prudential framework by the EU co-legislators to mitigate the impact on banks’ CET1 capital of the transition to IFRS 9 impairment requirements. As the phasing-in rules could have an impact on some banks’ capital ratios, the ECB is monitoring the correct application of the phasing-in rules.

Thematic review of BCBS 239

A report on the thematic review on effective risk data aggregation and risk reporting was published in May 2018

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) principles on risk data aggregation and risk reporting were published in January 2013. Against this background, a thematic review on banks’ risk data aggregation and risk reporting was conducted between 2016 and 2018, covering a sample of 25 SIs. The outcome was published in the form of a dedicated report on the ECB’s website in May 2018. The report revealed that the SIs covered had implemented the BCBS 239 principles in an unsatisfactory manner. The results of the review were communicated to the banks and requests for remedial action were set out in follow-up letters. In this context, the banks were also requested to submit clear, accurate and detailed action plans. The centralised working group, supported by the JSTs, has assessed these action plans in order to ensure horizontal consistency and is now closely monitoring the banks’ progress in implementing them.

The methodology used in the thematic review will enrich the supervisory assessment methodology on risk data aggregation and risk reporting. Currently, a dedicated drafting team is incorporating this methodology into the SREP methodology, which will be used for all SIs in the future.

The review was guided by the principles for effective risk data aggregation and risk reporting issued by the BCBS. As the ECB monitors how institutions’ risk data aggregation and risk reporting capabilities are improving, it regularly informs and updates the BCBS’s Risk Data Network on relevant insights.

Thematic review of outsourcing

In recent years, technological developments have affected the way banking services are offered worldwide. Outsourcing, for instance, may help banks to be more efficient, but it may also pose challenges for them in terms of their risk management and the ways in which they control outsourced activities. Banks are also showing increasing interest in outsourcing to cloud service providers. While cloud services can offer some advantages (e.g. economies of scale and cost-effectiveness), they also present challenges in terms of data protection and data location.

Against this backdrop, ECB Banking Supervision has been keeping a close eye on outsourcing, which was identified as one of the SSM supervisory priorities for 2017. To this end, a thematic review involving a targeted sample of SIs was launched and concluded in 2017, with follow-up actions continuing in 2018 as part of ordinary ongoing supervision. The thematic review took stock of banks’ outsourcing practices, revealing significant differences in terms of their governance and management. ECB Banking Supervision also identified best practices in order to promote further improvements. Based on the thematic review, it has contributed to the EBA’s work in relation to (i) the EBA Recommendations on outsourcing to cloud service providers[11], and (ii) the new EBA Guidelines on outsourcing, which will replace the CEBS Guidelines and the aforementioned recommendations, when they enter into force later in 2019.

In these documents, the EBA addresses a number of relevant issues which arose during ECB Banking Supervision’s thematic review. Overall, the EBA Recommendations deal with specific features of material cloud outsourcing, such as security and location of data and systems. Other relevant aspects, such as ensuring access and audit rights in written outsourcing agreements, confidentiality matters, exit strategies and sub-outsourcing or “chain” outsourcing, are covered in the revised Guidelines. A duty to maintain a register of information for all outsourcing activities and to make it available to supervisors, on request, has also been introduced.

Under the revised EBA framework, ECB Banking Supervision aims to ensure that banks take full advantage of innovative advancements while maintaining a secure environment, with risks duly monitored and mitigated. To this end, it has embedded the EBA Recommendations in its supervisory standards, duly taking them into account in the context of ongoing supervision. ECB Banking Supervision is also committed to implementing the Guidelines and will monitor the actions taken by banks to adapt their outsourcing arrangements. Furthermore, it is paying attention to the outsourcing-related challenges arising from Brexit and banks’ relocation plans, in order to ensure that outsourcing arrangements do not hinder effective supervision.

1.5 Ongoing supervision

ECB Banking Supervision strives to supervise SIs in a risk-based and proportionate manner, while, at the same time, being tough and consistent. To that end, each year a set of core ongoing supervisory activities is defined. These activities draw on the existing regulatory requirements, the SSM Supervisory Manual and the SSM supervisory priorities. They are included in the ongoing supervisory examination programme (SEP) for each of the SIs.

In addition to these centrally defined core activities, JSTs can adapt supervisory activities to banks’ specificities, where appropriate. This allows them to address rapidly changing risks at individual institutions or at the level of the entire system.

In 2018 ongoing SEP activities comprised: (i) risk-related activities (i.e. SREP and stress testing); (ii) other activities related to organisational, administrative or legal requirements (e.g. the annual assessment of significance); and (iii) additional activities that are planned by JSTs to further adapt the ongoing SEP to the specificities of the supervised group or entity (e.g. analyses of specific topics such as selected credit portfolios and asset classes).

Being proportionate

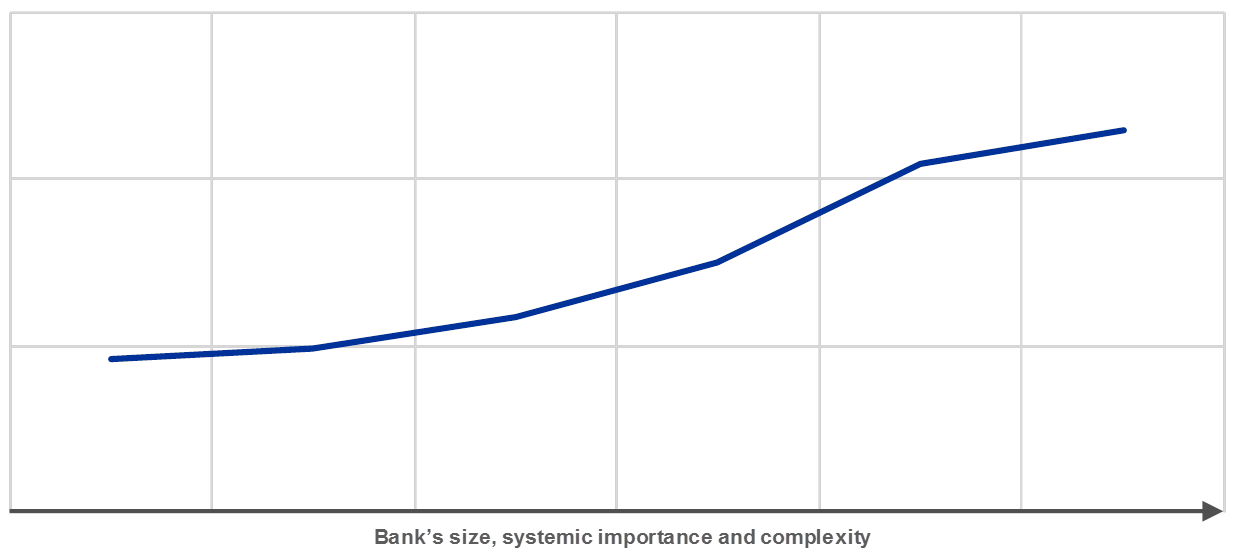

Supervisory activities in 2018 followed the principle of proportionality, tailoring the intensity of supervision to the systemic importance and risk profile of the supervised banks

The SEP follows the principle of proportionality, i.e. the intensity of supervision is tailored to the size, systemic importance and complexity of each institution. It is these factors that determine the overall number of ongoing activities performed for any particular institution (see Chart 4).

Chart 4

Average number of tasks per SI in 2018

Source: ECB.

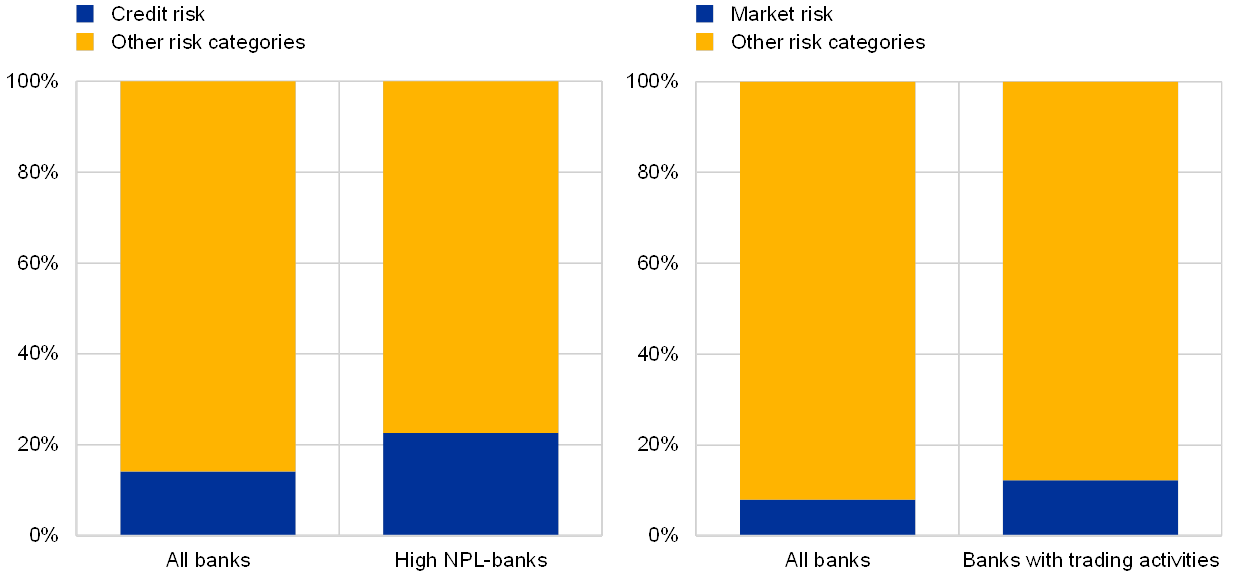

Taking a risk-based approach

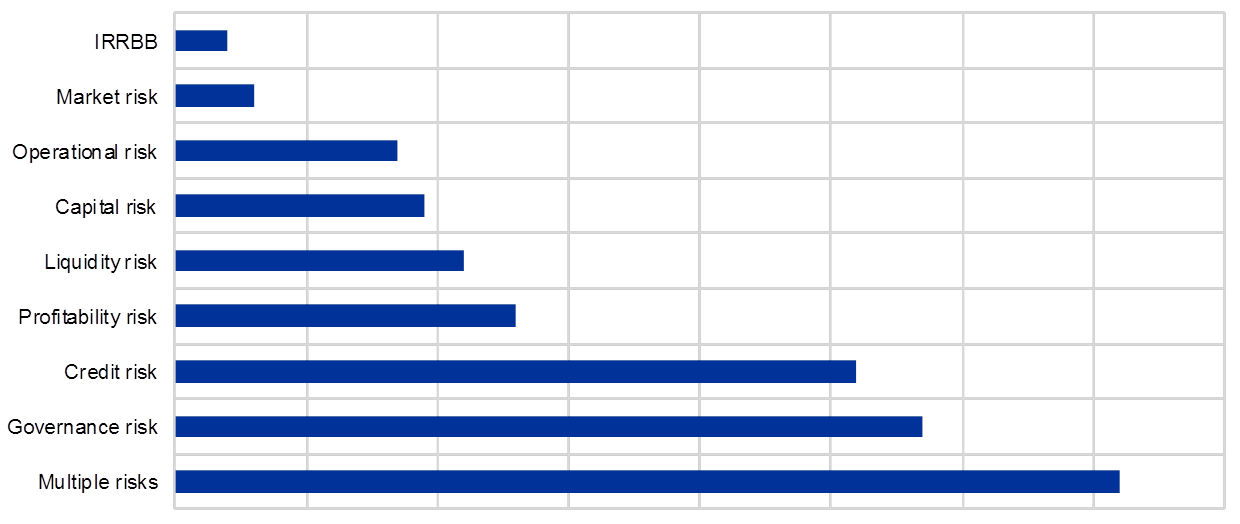

The SEP also follows a risk-based approach, focusing on the most relevant risk categories for each SI. Banks with high levels of NPLs serve as an example. For these banks, dedicated tasks, such as assessing NPL reduction strategies against the ECB’s expectations, were carried out in 2018. As a result, the percentage of tasks related to credit risk for high-NPL banks was higher than for the average bank. The same applies to institutions with high exposures to market and trading activities. These banks were the subject of more intense supervision for market risk-related issues (see Chart 5).

Chart 5

SEP activities in 2018: focus on credit and market risk

Source: ECB.

Note: Only planned activities related to risk categories were considered.

Highlights of ongoing supervision in 2018

In the context of the ongoing 2018 SEP, activities related to the SREP assessment, the conduct of the EU-wide stress test and the follow-up to the IRRBB (interest rate risk in the banking book) sensitivity analysis were particularly significant for JSTs.

The SREP is one of the JSTs’ key tasks. JSTs were involved in the SREP exercise throughout 2018, with some peaks in activity in relation to key milestones, such as the preliminary assessment of capital, liquidity and qualitative measures and the production of draft decisions. To be able to include the results of the EU-wide stress test, the deadline for drafting the final decision letters was extended to January 2019.

Another activity that required considerable JST involvement was the supervisory stress-testing exercise. This exercise comprised the EU-wide stress test (on 33 SIs included in the EBA sample) and the ECB’s own stress test (on 54 SIs which were not part of the EBA sample).[12]

One additional key activity performed by the JSTs in 2018 was the follow-up to the IRRBB sensitivity analysis conducted in 2017. Those banks in respect of which the exercise revealed potential vulnerabilities were subject to a follow-up by the JSTs in the first quarter of 2018. The remedial actions taken in response to the individual findings were monitored throughout the year as part of the ongoing supervisory dialogue with the banks.

Deep dives

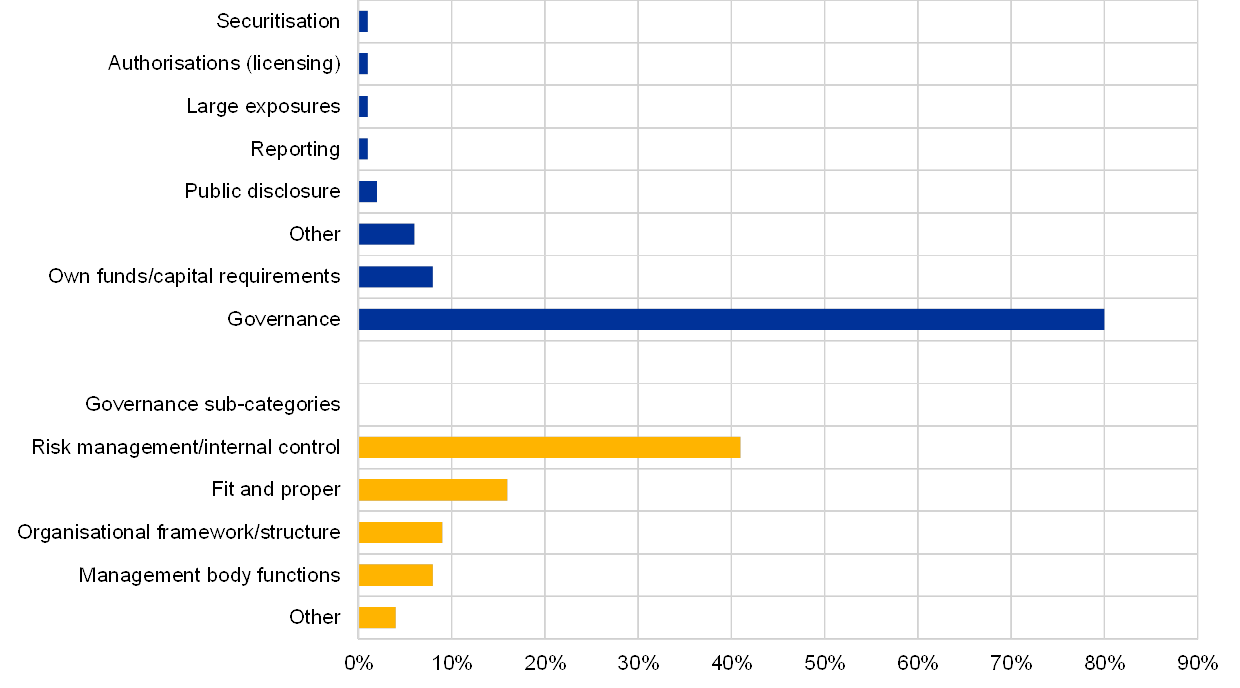

As a part of ongoing supervision, JSTs have the discretion to address institution-specific risks. They do so, for instance, by setting the scope of the deep dives, i.e. analyses of idiosyncratic issues, which are part of the SEPs. In 2018 the JSTs focused mostly on governance, credit risk, and business models and profitability. This focus broadly reflected the 2018 supervisory priorities (see Chart 6).

Chart 6

Deep dives and analyses by risk category in 2018

Source: ECB.

Status of SEP activities

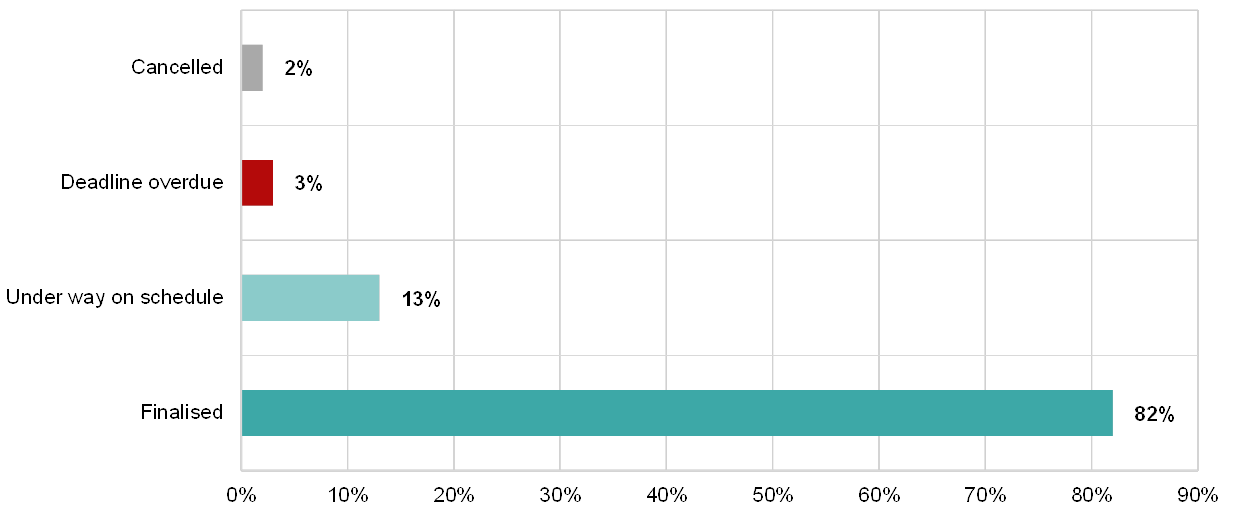

The 2018 SEPs were successfully executed, with a 95% implementation rate

The 2018 SEPs were successfully executed. At the end of the year, 95% of all activities had been implemented. Of these, 82% had been completed, while 13% were still being executed as planned (e.g. the assessment of recovery plans, which began in 2018 and was planned to be completed in 2019). Another 3% of activities will be completed with some delay, and 2% of activities were cancelled, mainly owing to changes in bank structures or licence withdrawals (see Chart 7). The key activities were performed according to plan, though, covering the main risks for the banking system. Overall, the low proportion of delays and cancellations confirms the suitability and stability of the ongoing SEPs, as well as the JSTs’ ability to carry out activities according to plan.

Chart 7

Completion rate in 2018

Source: ECB.

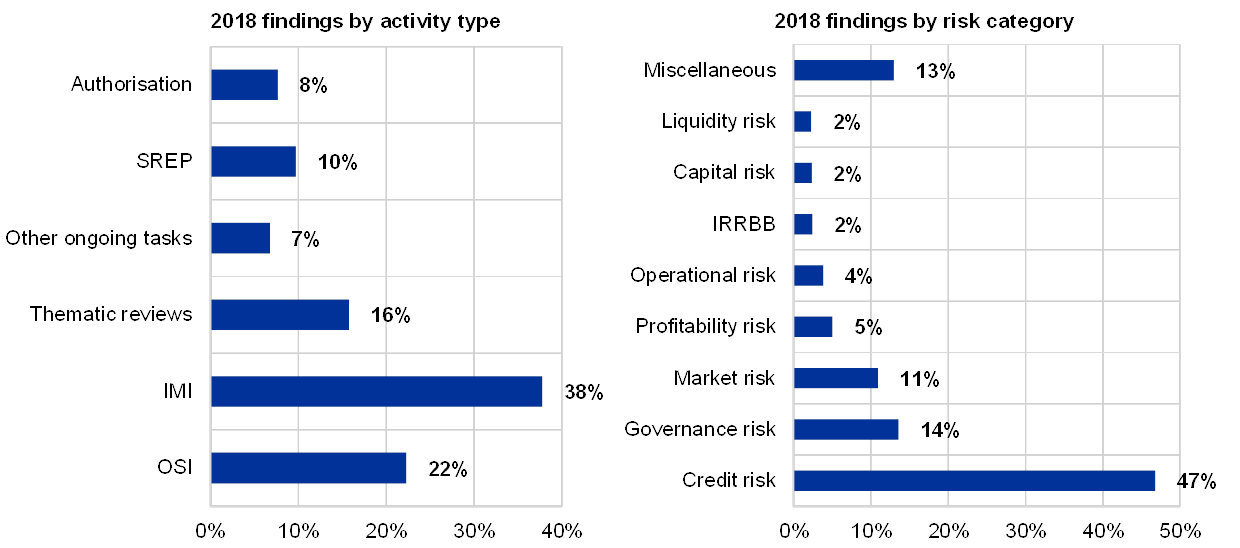

Supervisory findings

One of the main outcomes of regular supervisory activities are the “supervisory findings”, in other words, shortcomings which need to be remedied by the banks. JSTs are responsible for monitoring how banks follow up on these findings. The annual number of registered findings has stabilised after increasing in the first few years of the SSM. In 2018 the majority of findings originated from internal model investigations (partly owing to the TRIM project, which increased supervisory involvement), OSIs and thematic reviews (e.g. of business models and profitability, see Chart 8).

Chart 8

Supervisory findings

Source: ECB.

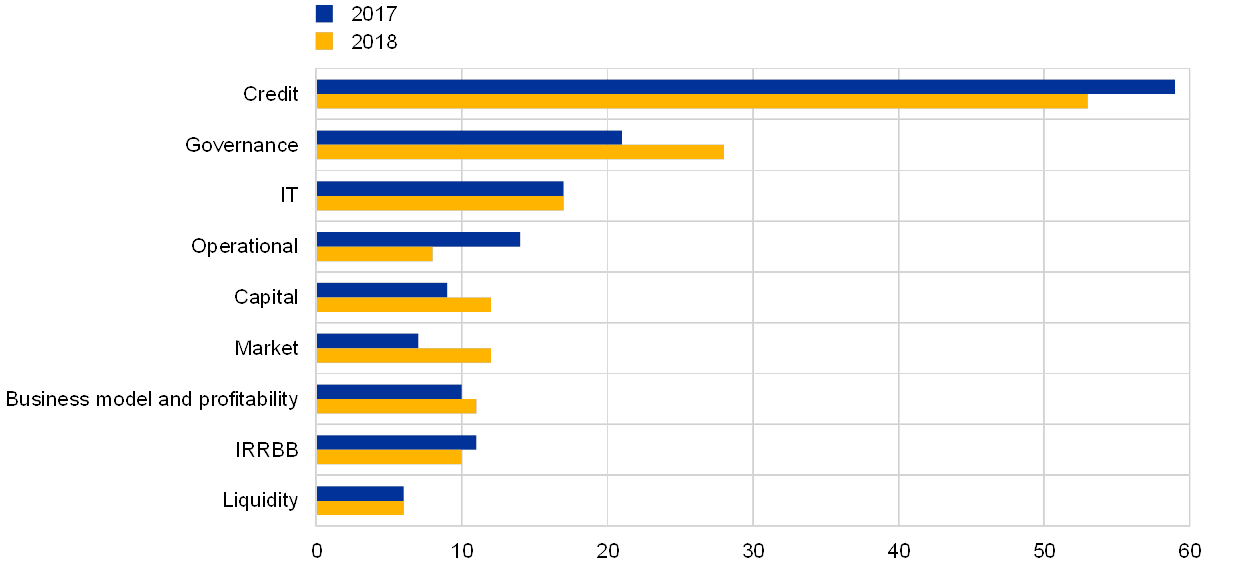

1.6 On-site supervision

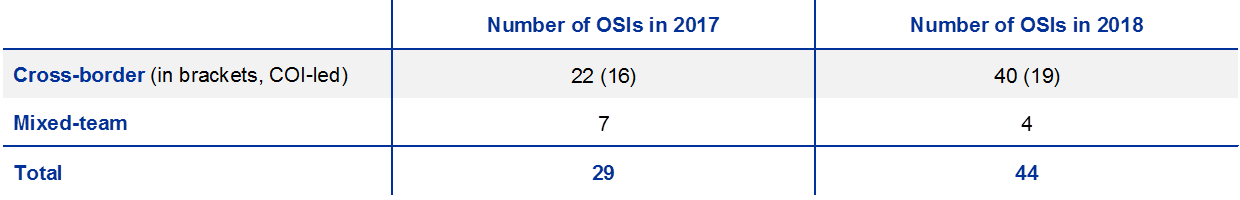

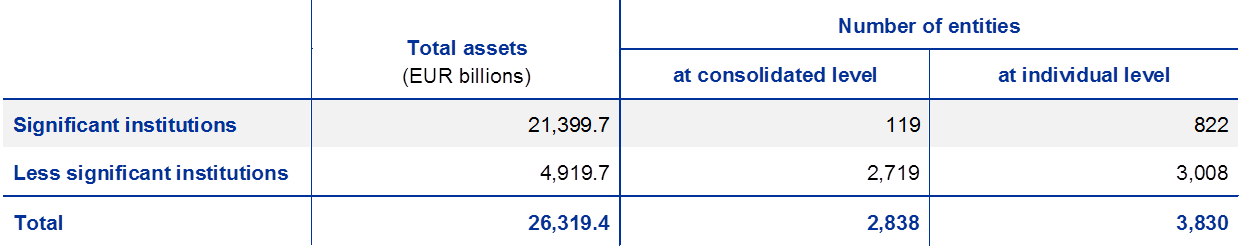

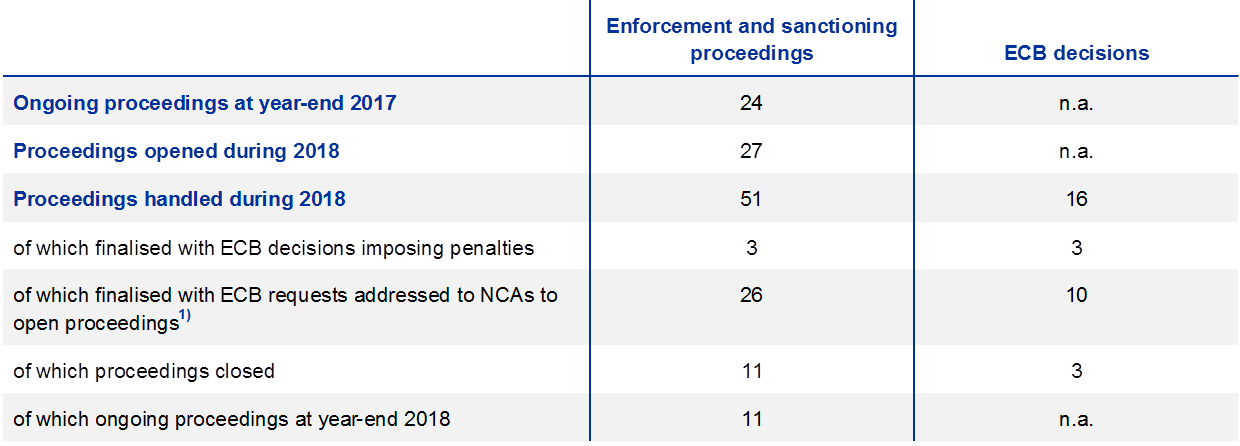

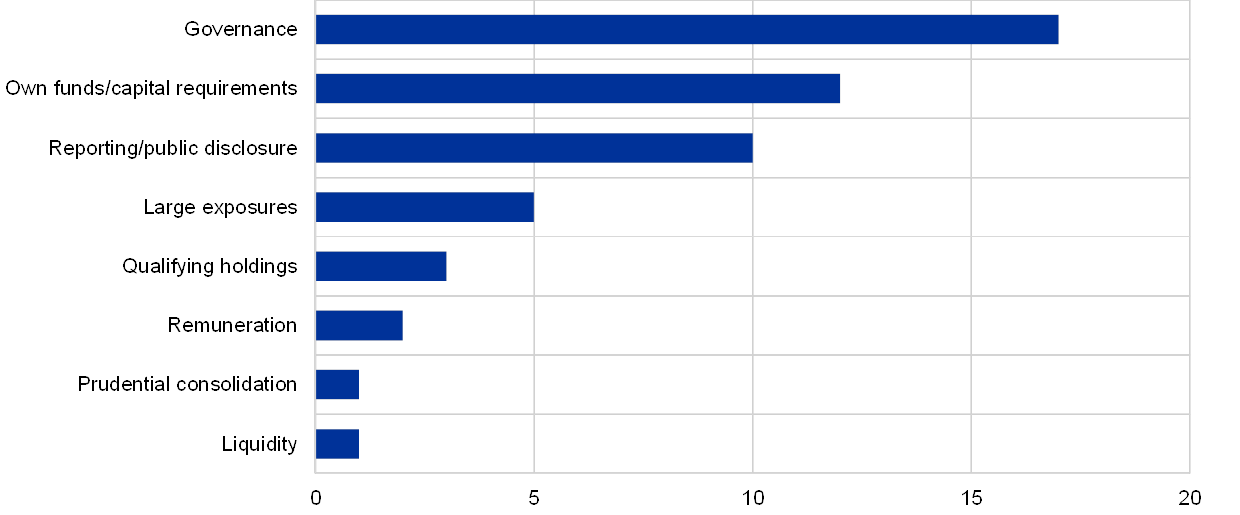

A total of 156 on-site inspections were launched in 2018