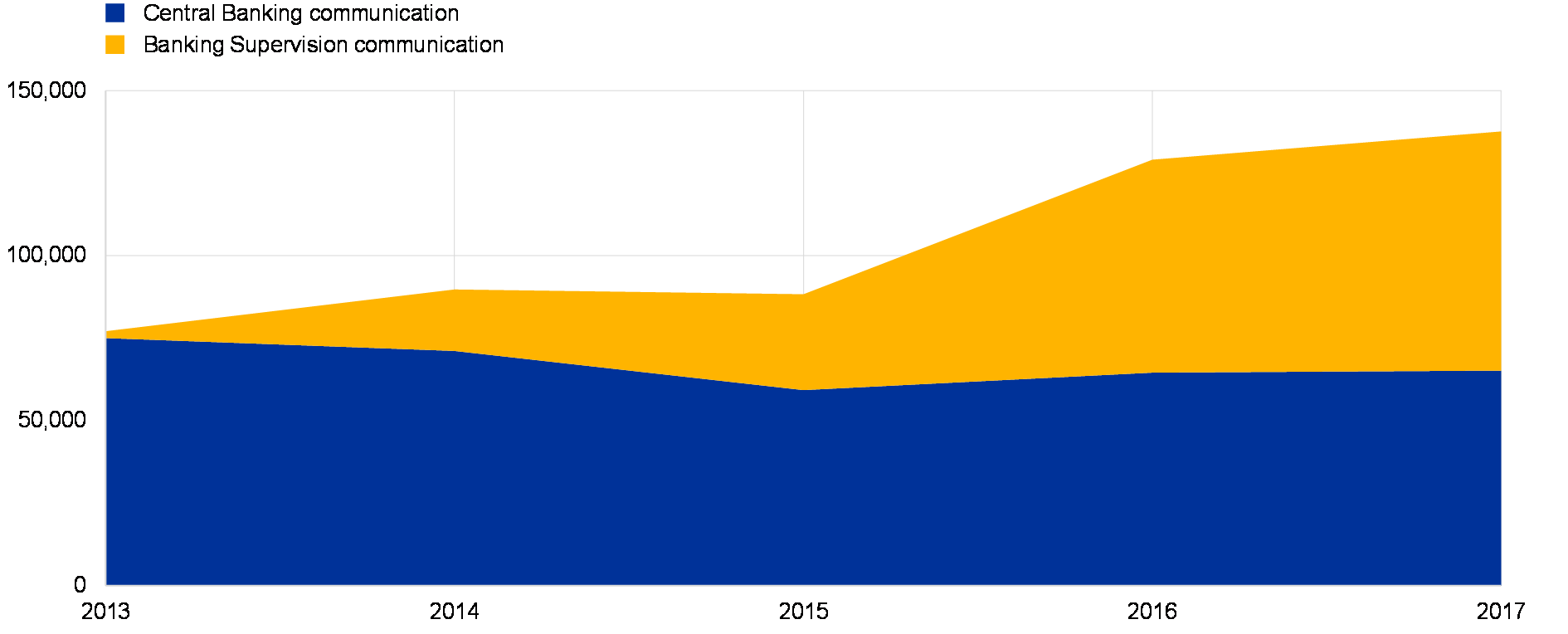

Foreword by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB

The financial crisis started ten years ago, bringing pervasive economic, social and financial instability. Dramatic falls in output, employment and lending to the economy, together with the fragmentation of the financial system along national lines, plagued the euro area for several years. The stability of the banking system was threatened and many doubted the survival of the euro.

The crisis exposed several institutional weaknesses in the euro area, in particular the lack of an integrated banking market – the pillars of which are a single supervisor, a single resolution authority with a single resolution fund and a single deposit insurance scheme. As part of their reaction to the turbulence of 2012, policymakers created a single supervisor, which they hosted at the ECB. In the space of two short years, with the participation of the national competent authorities, European banking supervision was built.

Today, the euro area economy has been expanding for almost five years and growth is broad-based across countries and sectors. The ECB’s monetary policy has been the main driver of the recovery, and its actions have been complemented in important ways by banking supervision at the euro area level.

First, integrated banking supervision has contributed to making banks stronger, which has helped overcome financial fragmentation, improve the transmission of monetary policy and restore credit provision to households and firms. Lending rates across the euro area have converged to record lows.

Second, by requiring banks to hold adequate capital and ensuring that they strike a sustainable balance between risk and return, European banking supervision has been the first line of defence against financial stability risks originating in the banking sector. This has enabled monetary policy to pursue its price stability mandate, even when the policy stance needed to remain accommodative for a long time, because risks to financial stability were and are being contained by effective supervision.

In 2018 banks continue to face some key challenges. These include cleaning up their balance sheets, reducing legacy exposures largely originating from the financial crisis, such as certain non-marketable financial products, and from the ensuing Great Recession, such as non-performing loans. They also include the need to adapt their business models to new technological challenges, as well as to address issues of overcapacity and high costs. These must remain the priority action areas for banks that strive to be strong and to serve the euro area economy.

Introductory interview with Danièle Nouy, Chair of the Supervisory Board

Almost ten years have passed since the failure of Lehman Brothers and the start of the financial crisis. Has the financial system become safer since then?

The global financial crisis undoubtedly triggered many changes. At global level, we have just finalised a comprehensive regulatory reform – Basel III. Rules for banks have become tougher and gaps in the regulatory framework have been closed. At European level, we have started to build a banking union. Currently, the banking union rests on two pillars: European banking supervision and European bank resolution. Together, they help to enhance supervision of banks across Europe and to deal with crises more effectively. All in all, it is fair to say that the existing architecture of the financial system was largely shaped by the crisis. And this architecture is much more stable than the previous one. So yes, the financial system has become a safer place.

What about the banks themselves? Did they learn their lesson?

Well, I hope so. After all, one of the root causes of the crisis was a culture which prioritised short-term gains over long-term sustainability, and which often neglected the impact of banks’ actions on the economy and on taxpayers. This culture needs to change; and this change has to come from the banks, although regulators must ensure that incentives are, and stay, consistent.

What incentives do you have in mind?

The fact that banks can now fail in an orderly fashion should, above all, shift their focus towards sustainability. Public bailouts should be a thing of the past. In Europe, the Single Resolution Mechanism plays a key role here. It passed its first test in 2017, when three large banks failed and were resolved or wound down. The message is clear: banks now have to face up to the consequences of their behaviour; if they act unwisely, they might fail.

So the threat of failure prompts banks to start tackling all the challenges they face?

Yes, of course. Banks have come a long way since the crisis, but there are still challenges that need to be addressed. And now is the time; the conditions are ideal for four reasons. First, the euro area economy is doing well. Second, new technologies might be a challenge to banks, but they also offer new opportunities for banks to earn money and remain profitable. Third, there is regulatory certainty as Basel III has been finalised. And fourth, there is supervisory certainty now that European banking supervision is fully in place. Banks know how we work and what they can expect from us.

Profitability is a major challenge for banks in the euro area, right?

Indeed, profitability is the number one challenge for banks in the euro area. A number of them still don’t earn their cost of capital, and in the long run that’s an unsustainable position. While it’s a problem for the banks themselves, it’s also an issue that worries us supervisors. Unprofitable banks cannot support economic growth and build up capital buffers. At the same time, they might embark on a search for yield, which would increase risks. So we supervisors are concerned about the lack of profitability in the euro area banking sector.

What steps should banks take to increase their profitability?

That’s a more difficult question as each bank is different, and each bank needs its own strategy. The starting point for each and every bank is to have a strategy and to implement it. Here, the concept of “strategic steering” comes into play. In a nutshell, it refers to the management’s ability to set a course towards the bank’s long-term objectives. This requires sound processes and good governance, including risk management. If these conditions are met, the management has, at all times, a good overview and understanding of the entire organisation and can quickly change course if necessary. On the whole, the better banks are at “strategic steering”, the more successful they are. On a more practical level, banks should think about diversifying their sources of income, for instance through new technologies. For large banks in the euro area, more than half of operating income consists of net interest income. Given the record-low interest rates, this is something to work on. Banks could, for instance, try to increase their fee and commission income. Many banks have indicated that they indeed plan to do so. But, as I said, each bank is different, and each needs to find its own way. More generally, the European banking sector needs to further consolidate.

What about costs? Wouldn’t cost-cutting be another path to higher profits?

There is room to cut costs, that’s true. Look at the large branch networks: are they still needed in times of digital banking? Cutting costs might be part of a bank’s strategy to become more profitable. There’s a caveat, though: banks mustn’t make cuts in the wrong places. Reducing staff in areas such as risk management? Not a good idea. Saving on IT systems? Not a good idea either. In more general terms, banks must not save on things that are crucial for future success and stability.

Do non-performing loans affect profitability?

Yes, very much so. Non-performing loans, or NPLs, are a drag on profits, and they divert resources that could be used more efficiently. Given that NPLs in the euro area amount to almost €800 billion, they pose a major problem that needs to be resolved. The good news is that banks are making progress: since early 2015, NPLs have fallen by about €200 billion. This is encouraging, but it’s not enough.

What major steps has European banking supervision taken to help resolve the problem of non-performing loans?

NPLs are one of our top supervisory priorities. In early 2017, we published guidance to banks on how to deal with non-performing loans. Using that guidance as a reference point, we have scrutinised the banks’ own plans to address NPLs. In 2018 we will continue to monitor how these plans are being implemented.

But banks not only need to get rid of existing NPLs. They also need to deal with potential new ones. To that end, we published a draft addendum to our guidance at the end of 2017. It lays out how we expect banks to provision for new NPLs – these expectations are non-binding, of course. This is the starting point for the supervisory dialogue and will feed into our bank-by-bank approach. The draft addendum was subject to a public consultation, and a final version was published in March 2018.

So banks still need to clean up their balance sheets.

Yes, the good times won’t last forever, so banks should make the most of them while they can. When a downturn comes, it will become much more difficult to reduce NPLs. More generally, clean balance sheets are key to profitability in the short and medium term. In this context, the European Banking Authority’s stress test in 2018 will be a moment of truth for banks. It will help to assess how resilient the banks will be when the going gets tough.

Besides low profitability and non-performing loans, what else does European banking supervision have to monitor?

Many things. We are, for instance, taking a close look at the internal models that banks use to determine the risk weights of their assets. This is highly relevant for calculating capital requirements and thus for the resilience of banks. In order to ensure that the models yield adequate results, we are conducting a targeted review of internal models – or TRIM, as we call it. The review has three objectives: first, to ensure that the models used by banks are in line with regulatory standards; second, to harmonise the way in which supervisors treat internal models; and third, to ensure that the risk weights calculated with internal models are driven by actual risk and not by modelling choices. TRIM will help to raise trust in internal models, in capital adequacy and, hence, in the resilience of banks.

Is the targeted review of internal models also related to Basel III and the much-discussed output floor?

There is indeed a connection. As a general rule, Basel III seeks to preserve risk-based capital requirements. This makes perfect sense as risk-based capital requirements are efficient and prompt banks to carefully define, measure and manage their risks. In this context, internal models are key. If they don’t work properly, banks might end up undercapitalised and vulnerable. And as I just mentioned, TRIM seeks to ensure that internal models work properly. It does so bottom-up, if you will, by assessing the models themselves. At the same time, Basel III introduces some top-down safeguards, such as the output floor you mentioned. It ensures that the risk weights calculated with internal models do not fall below a certain level. So, just like TRIM, the output floor helps to make risk-based capital requirements credible. This is very much in the interest of banks.

Turning from Basel to the UK: how is European banking supervision preparing for Brexit?

Well, Brexit will most certainly change Europe’s banking landscape. And it affects banks on both sides of the Channel. Their main concern is to retain access to each other’s market. To do that, they might have to implement far-reaching organisational changes, and such changes need to be prepared well in advance, of course.

But supervisors too need to prepare for the post-Brexit world. We have developed a number of policy stances on relevant issues, and we have made clear what we expect from banks that relocate to the euro area. We keep in close contact with the banks concerned through various channels. This helps us to better understand their plans and to clearly communicate our expectations.

But the changes triggered by Brexit go beyond the relocation of some banks that operate from the UK. As supervisors, we have to think about cross-border banking groups more generally: how can we ensure that they are well supervised, that they are resolvable? This will not only affect banks that operate from the UK, but also banks that operate from any other third country. And it may also affect European banks that operate outside the EU.

Looking beyond Brexit, how do you see financial integration developing in Europe?

Brexit is a sad story; that much is certain. But it is equally certain that financial integration in Europe will continue. Work on Europe’s banking union is well advanced, and the idea seems to appeal to countries outside the euro area as well – eastern European and Scandinavian countries in particular. I find this encouraging.

However, the banking union still needs to be finalised, and its third, missing pillar is a European deposit insurance scheme, or EDIS. Now that banking supervision and bank resolution have been transferred to the European level, the same should happen to deposit protection. Only then will control and liability be aligned. In my view, it is time to take further steps towards EDIS.

As the banking union makes progress, banks should start to reap the benefits of a large and integrated market; they should reach more across borders, and form a truly European banking sector, which reliably and efficiently finances the European economy.

1 Supervisory contribution to financial stability

1.1 Credit institutions: main risks and general performance

Main risks in the banking sector

Although some improvements can be observed, the SSM risk map remains largely unchanged

The economic environment within which euro area banks operate continued to improve over the past year, and some banks were able to generate significant profits, although some others still need to recover. Overall, banks made sound progress in strengthening their balance sheets and tackling non-performing loans (NPLs). At the same time, work on completing the regulatory agenda also advanced, helping to lessen regulatory uncertainty.

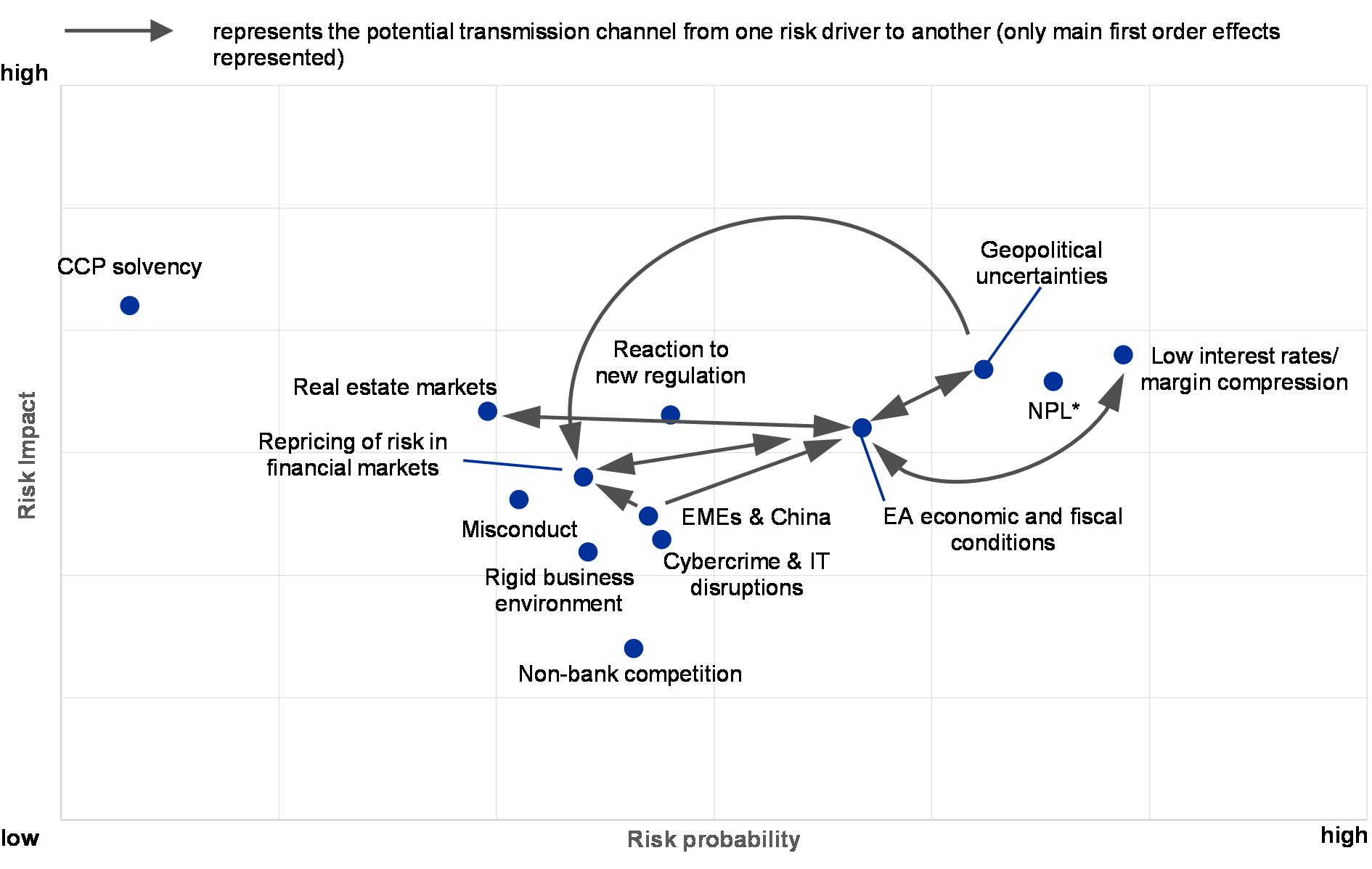

Chart 1

SSM risk map 2018 for euro area banks

Source: ECB and national supervisory authorities.

Notes: The risk map shows the probability and impact of risk drivers, ranging between low and high.

*NPLs: this risk driver only concerns euro area banks with high NPL ratios.

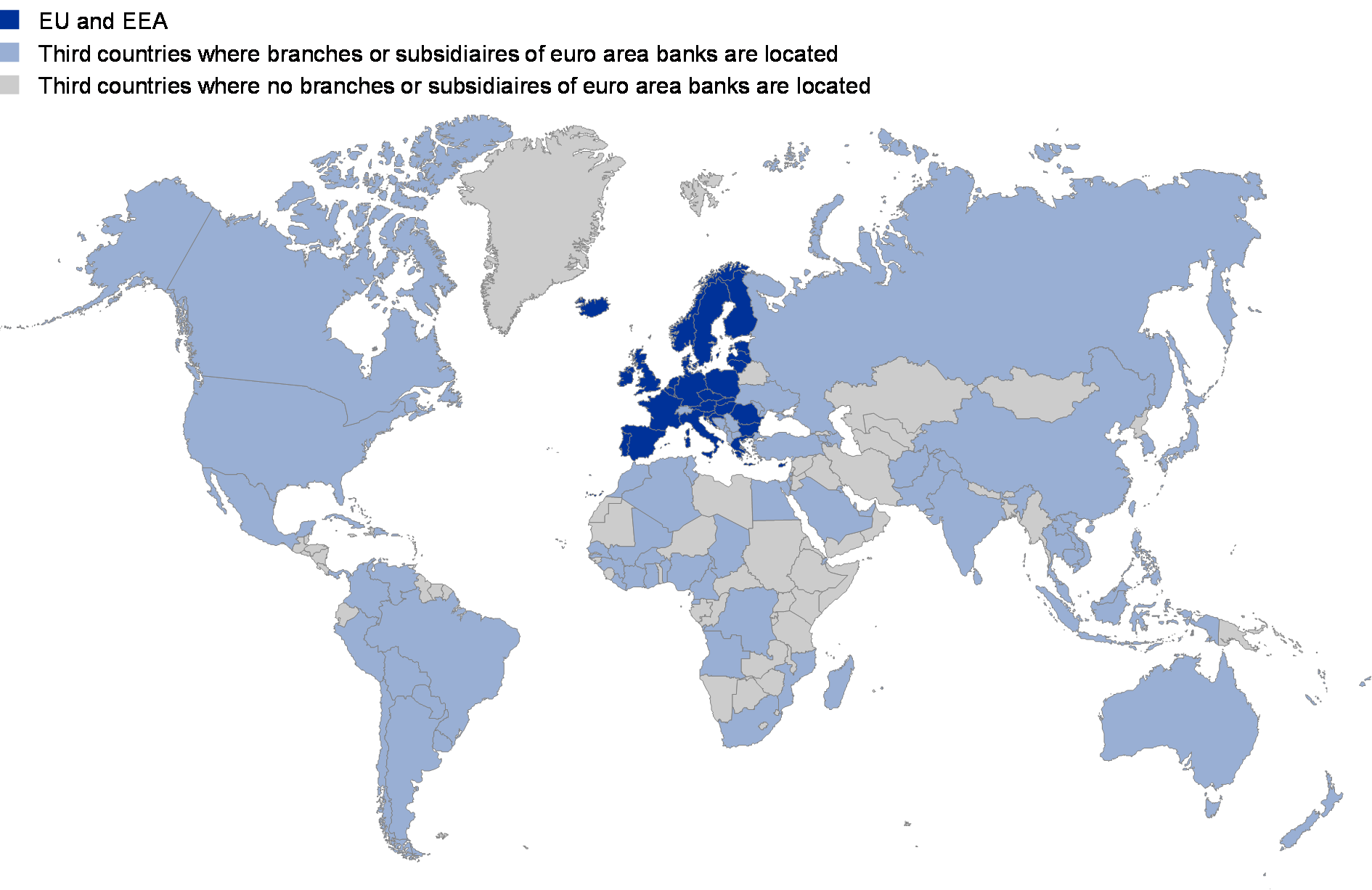

However, some risks persist, and the overall SSM risk map (see Chart 1) has not changed considerably since the beginning of 2017. The three most prominent risk drivers, both in terms of potential impact and probability, are (i) the low interest rate environment and its adverse effects on banks’ profitability; (ii) persistently high levels of NPLs in parts of the euro area; and (iii) geopolitical uncertainties. The first two risk drivers have decreased somewhat since 2016. Geopolitical uncertainties, on the other hand, have markedly increased, mainly owing to ongoing negotiations on the final Brexit deal and more general global political uncertainty (at the same time, political uncertainty in the EU abated somewhat after the French presidential elections).

Profitability remains a key challenge

The prolonged period of low interest rates continues to present a challenge to banks’ profitability. While these low rates reduce funding costs and support the economy, they also compress net interest margins and hence weigh on banks’ profitability. Banks may thus need to adapt their business models and cost structures. At the same time, supervisors have to ensure that banks do not take excessive risks to increase their profits.

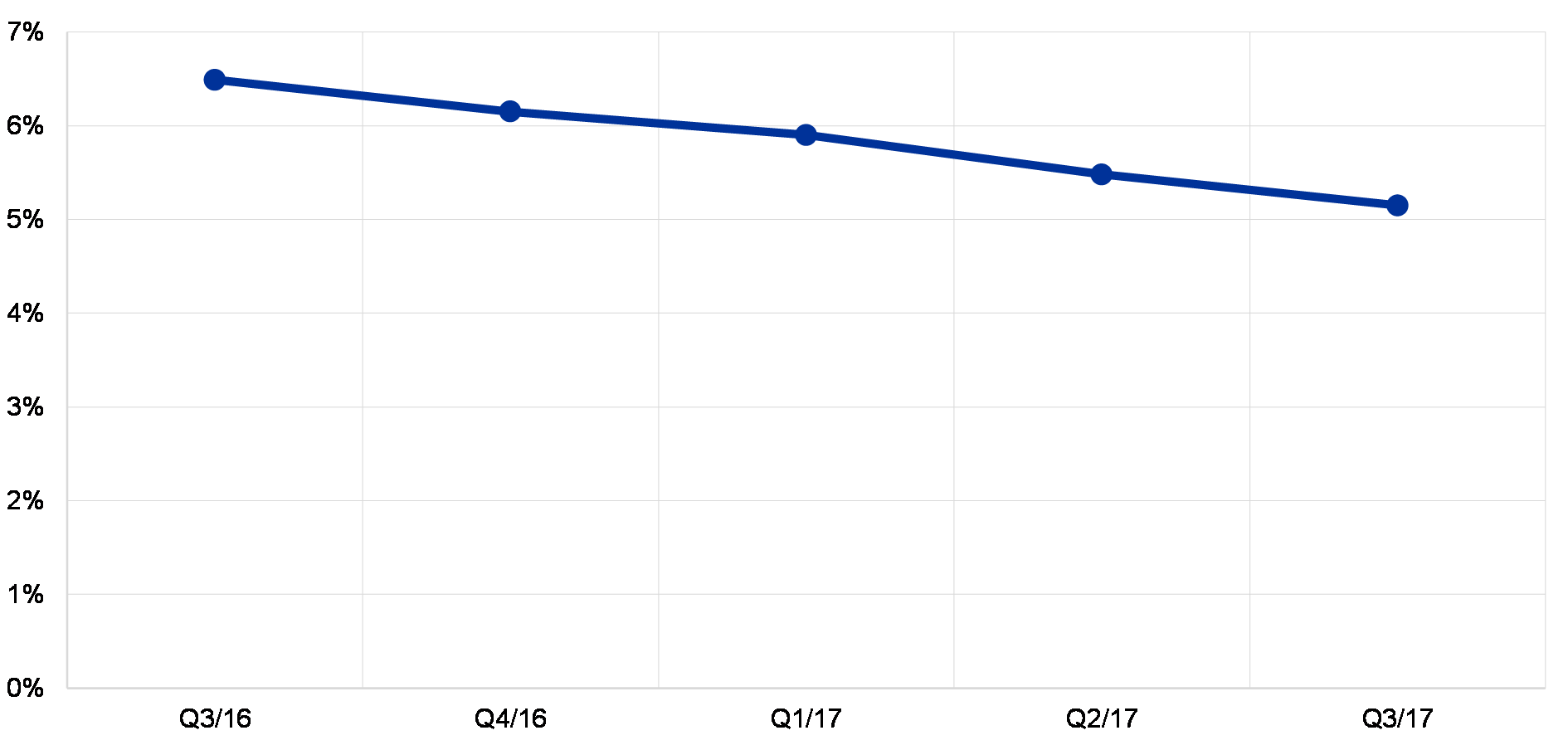

NPLs have been somewhat reduced, but further work is needed

High levels of NPLs constitute another major concern for a significant number of banks in the euro area. Compared to 2016, banks have made some progress in tackling NPLs. This is reflected in a drop in the aggregate NPL ratio from 6.5% in the second quarter of 2016 to 5.5% in the second quarter of 2017. Nevertheless, numerous euro area banks still have too many NPLs on their balance sheets. It is therefore crucial that banks step up their efforts to build and implement ambitious and credible NPL strategies. At the same time, further reforms are needed in order to remove structural impediments to NPL workout.[1]

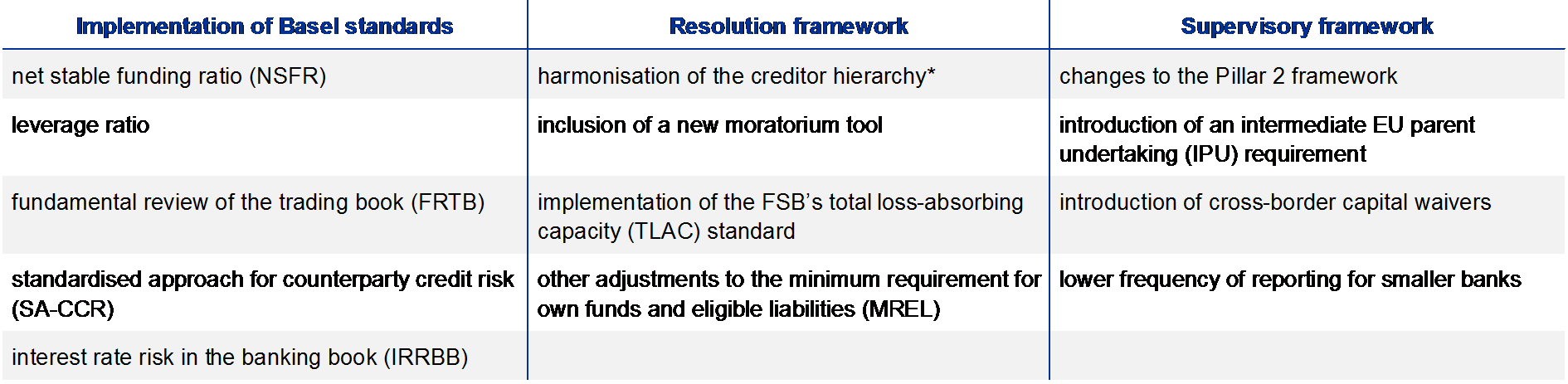

The implementation of the new regulatory framework may be a challenge for some banks

Finalising and fine-tuning the regulatory framework is conducive to banking sector stability in the medium term. However, the transition to the new regulatory landscape may involve short-term costs and risks for banks, including the failure to adapt in time. These risks have somewhat decreased since 2016 as more details have emerged about the final shape of various regulatory initiatives, following agreements reached in international and European fora.

Risk repricing may take place on the back of debt sustainability issues and geopolitical risks

Debt sustainability is still a concern in some Member States, which remain vulnerable to a potential repricing in bond markets (also owing to the current very low levels of risk premia). Sovereign risk is particularly relevant in the current context of historically high geopolitical uncertainty (to which Brexit contributes). Potential sudden changes in risk appetite on the financial markets could affect banks via the repricing of their mark-to-market holdings and funding costs.

SSM supervisory priorities

The SSM supervisory priorities set out focus areas for supervision in a given year. They build on an assessment of the key risks faced by supervised banks, taking into account the latest developments in the economic, regulatory and supervisory environment. The priorities, which are reviewed on an annual basis, are an essential tool for coordinating supervisory actions across banks in an appropriately harmonised, proportionate and efficient way, thereby contributing to a level playing field and a stronger supervisory impact (see Figure 1).

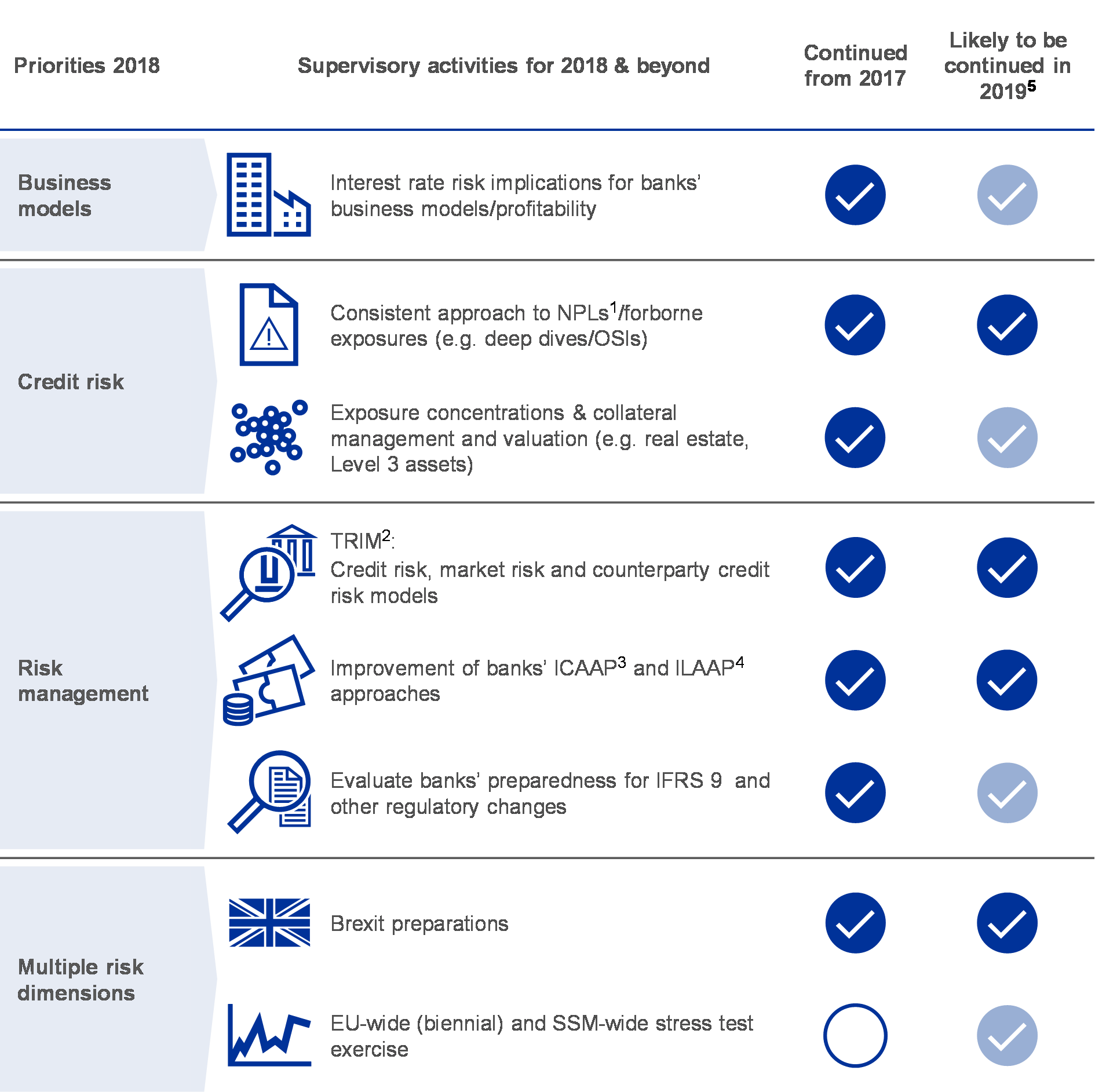

Figure 1

Supervisory priorities for 2018 and beyond

1) Non-performing loans.

2) Targeted review of internal models.

3) Internal capital adequacy assessment process.

4) Internal liquidity adequacy assessment process.

5) Light blue ticks indicate follow-up activities.

The outcome of the sensitivity analysis of interest rate risk in the banking book

The ECB is constantly monitoring the sensitivity of banks’ interest rate margins to interest rate changes. In the context of the low interest rate environment, which affects the profitability of the banking sector, the ECB decided to carry out a more in-depth assessment in 2017 of the strategies developed by banks to maintain the level of their interest margins under several scenarios.

Consequently, in the first half of 2017, ECB Banking Supervision ran a “Sensitivity analysis of interest rate risk in the banking book (IRRBB) – Stress test 2017”.[2] A sample of 111 significant institutions (SIs) was assessed based on two complementary metrics: (i) changes in the banks’ net interest income (NII) triggered by interest rate movements; and (ii) changes in the banks’ economic value of equity (EVE)[3] (i.e. the present value of their banking book) triggered by interest rate movements. The aim of the exercise was to achieve a supervisory assessment of risk management practices and to fully leverage the comparison of results across banks. To that end, the banks were asked to simulate the impact of six hypothetical interest rate shocks coupled with a stylised evolution of their balance sheets.[4]

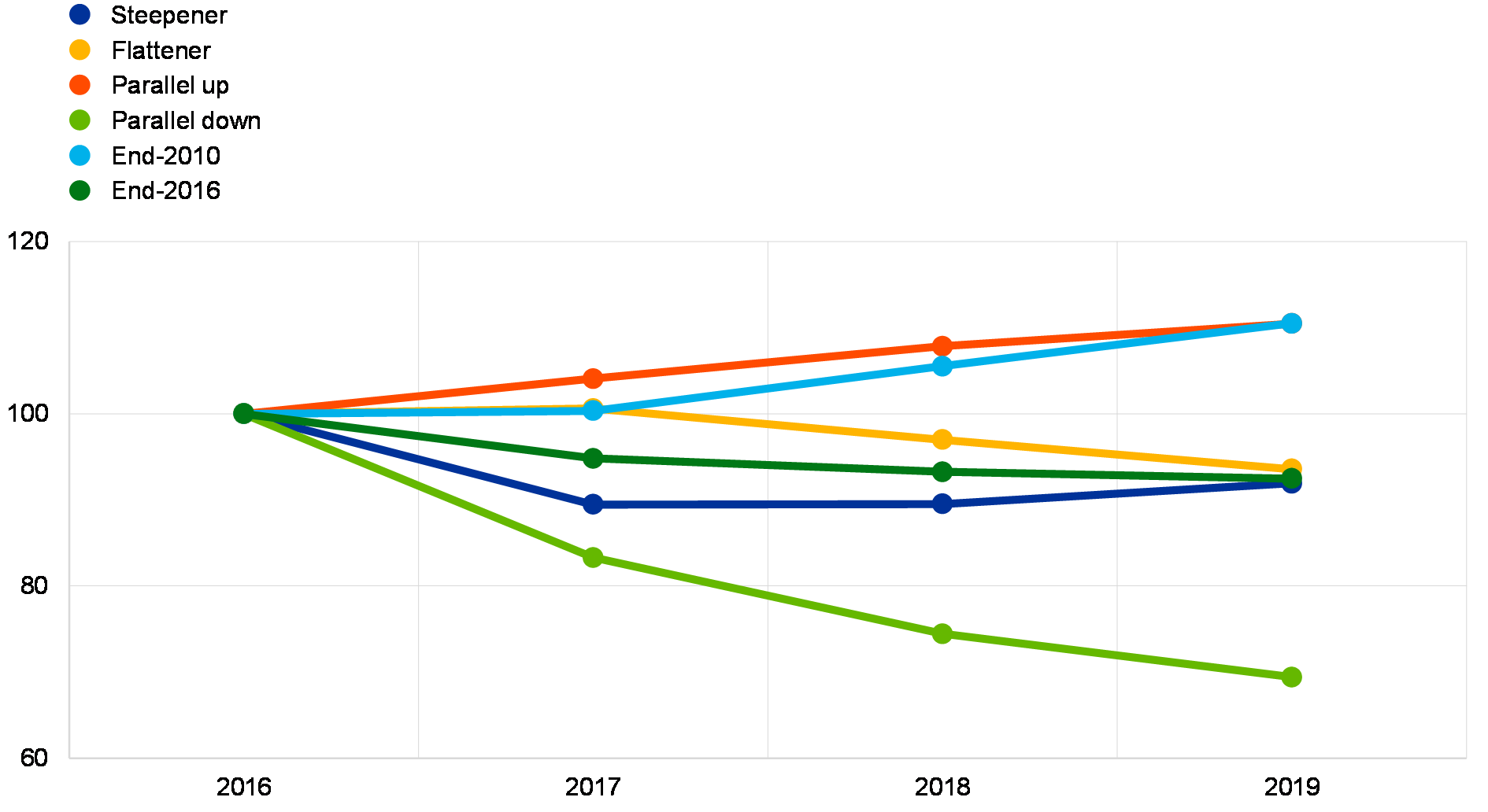

Chart 2

Average projected NII by interest rate shock

(index 2016 = 100)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Figures based on net interest income projections aggregated across all major currencies tested in the exercise for all 111 banks. The parallel shifts are currently used for the IRRBB reporting process (+/- 200 bps for EUR positions); the steepener and flattener are drawn from the recent BCBS Standards on IRRBB; the end-2010 shock envisages a return of interest rates to levels last seen in 2010; the end-2016 shock keeps rates constant at end-2016 levels.

The results show that, on average, banks are well equipped to cope with changes in interest rates. A sudden parallel shift of the term structure of interest rates by +2% would have an aggregate positive impact on NII (+10.5% over a three-year horizon, Chart 2) and a mild negative impact on the EVE (-2.7% of CET1, Chart 3), the latter being the most severe outcome for EVE across all the interest rate shocks considered.

However, the results of the exercise should not be misinterpreted as an absence of risks, especially as they take into account banks’ expectations regarding customer behaviour. For example, banks can model non-maturity deposits as long-term fixed-rate liabilities. In a period of rising interest rates, a repricing of these deposits faster than expected by the bank would result in a NII lower than expected. Banks mostly calibrated their deposit models on a period of decreasing interest rates. As such, the models may only partly reflect the reaction of customers to an increase in interest rates. Moreover, modelled durations of core deposits were found to be surprisingly long in some cases.

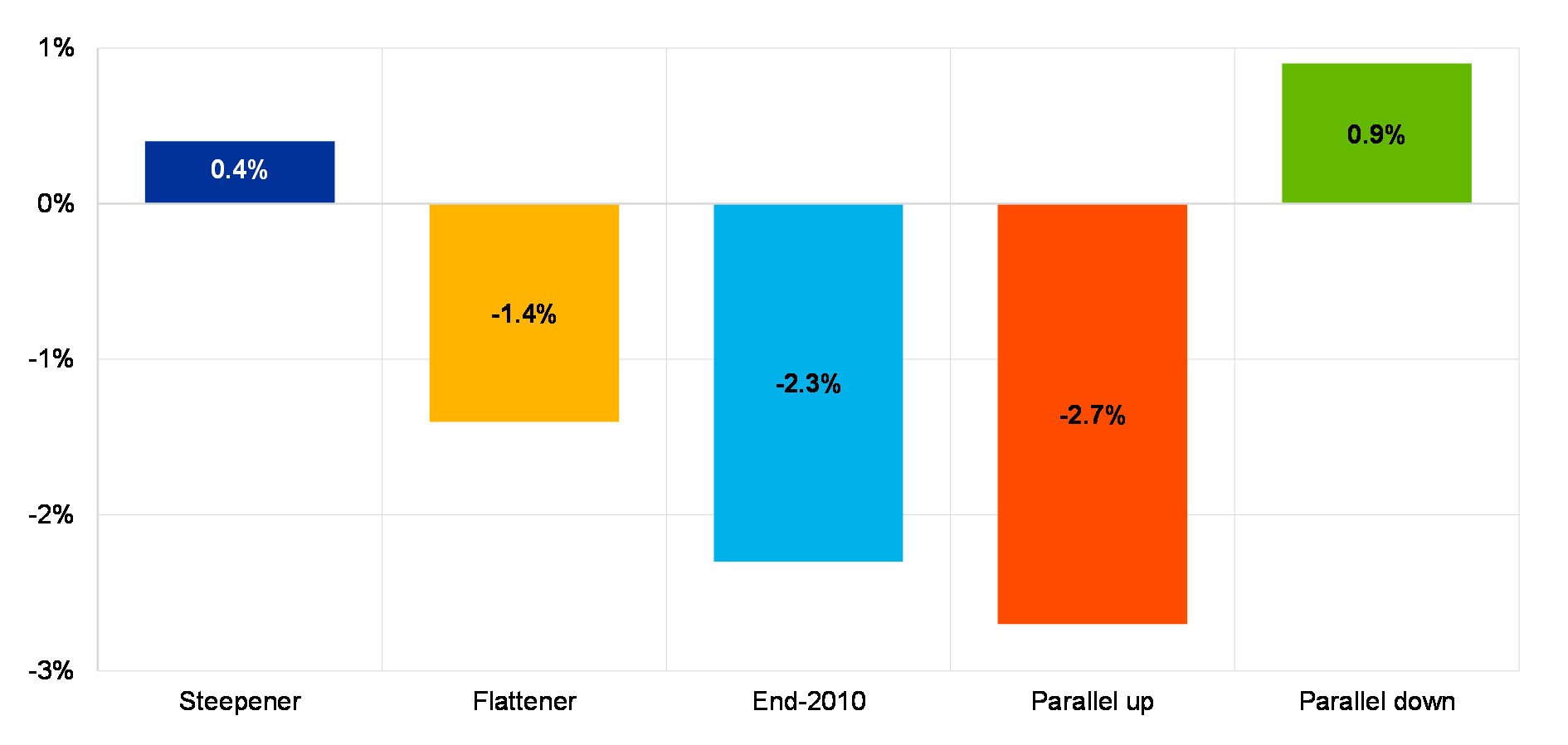

Chart 3

Average change in EVE by interest rate shock

(change in EVE as a percentage of CET1)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Figures based on aggregate EVE projections across all major currencies and aggregate CET1 capital for the full sample of 111 banks. There is no EVE change under the constant rates envisaged under the end-2016 shock.

The results also show that banks make significant use of interest rate derivatives in their banking books. In general, banks use derivatives to hedge mismatches in the repricing profiles of assets and liabilities. However, some banks also use interest rate derivatives to achieve a target interest rate profile. The aggregate impact across banks of these trades on EVE sensitivity is limited (+1.7% of CET1 under the parallel up shock). However, this limited impact is largely the result of offsetting exposures between those banks where derivatives reduce the duration of the assets and those where derivatives increase that duration (55% and 45% of the sample, respectively).

The results of the 2017 exercise fed into the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP). Going forward, the exercise will provide valuable input for supervisory discussions on interest rate risk in the banking book. The exercise could act as a starting point for follow-up analyses by Joint Supervisory Teams (JSTs).

Box 1

Banking sector consolidation – barriers to cross-border mergers and acquisitions

A healthy banking system goes together with a healthy market for bank mergers and acquisitions (M&A). The European banking union, including European banking supervision, will make it easier for banks to merge across borders.

Cross-border mergers within the euro area may bring three main benefits. First, it will deepen financial integration within the euro area, paving the road towards the common goal of a truly European banking sector. Second, savers will have more options when investing their money, and companies as well as households will be able to tap more sources of funding. Third, risk-sharing will be improved, helping the EU economy to become more stable and more efficient. Moreover, bank mergers can play a role in reducing excess capacity and making banks themselves more efficient. For these benefits to materialise, however, merger operations need to be prudentially sound.

The state of the M&A market

After an initial rise following the launch of the euro, mergers and acquisitions in the euro area have been declining. In 2016 they reached their lowest level since 2000, both in terms of the number of deals and their value.[5] And those mergers tend to be domestic rather than cross-border.

Bank mergers are complex, expensive and risky, and their success depends on certain enabling conditions. Banks need to be confident if they are to take that step, and it seems that banks still lack confidence at present.

In particular, there is often uncertainty about the economic value mergers bring. Looking at potential partners, there may be doubts about the quality of their assets and their ability to generate profits. In some parts of the euro area, levels of non-performing loans are still high, and their true value is hard to assess.

On top of this, there seems to be uncertainty about some key long-term drivers of bank performance. How will digitalisation and the associated changes in market structure affect the optimal structure and size of a bank, for instance? Is it still worthwhile to acquire branch networks when digital banking might make them less and less useful? And finally, some remaining uncertainty about regulation may also play a role. It seems that many banks would like to see the single rulebook fully implemented before they consider taking the big leap of merging with another bank.

Uncertainties are compounded by the cross-border dimension. First of all, cross-border mergers require banks not only to go beyond national borders, but also to overcome cultural and linguistic barriers. The lack of harmonisation in the legal and regulatory basis governing supervisory M&A reviews in the countries participating in the SSM may increase the costs of, and prove to be an obstacle to, cross-border M&A. The national laws that govern mergers tend to differ across countries.

More generally, the ring-fencing of capital and liquidity within jurisdictions plays a role. Options to waive cross-border intragroup requirements are currently being considered as part of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) and the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV) review and could, where introduced, play a supportive role for cross-border M&A. In addition, the CRD IV and CRR still contain a number of options and discretions which are exercised differently at national level. They make it difficult to ensure a consistent overall level of regulatory capital across Member States and to fully compare the capital positions of banks.

Of course, other regulatory factors can also play a role in banks’ decisions to consolidate. The additional capital requirements that may arise from an increase in the size and complexity of a bank, via other systemically important institution (O-SII) buffers or even global systemically important bank (G-SIB) buffers, may be a disincentive, for example.

Adding to the picture is the fact that part of the legislative framework (e.g. insolvency laws), tax systems, and regulations (e.g. consumer protection) which supports the functioning of financial systems remains diverse in the EU and in the euro area.

While European banking supervision can point out these obstacles, its role in shaping the environment is limited. Consolidation itself needs to be left to market forces, and changes to the regulatory landscape to the lawmakers.

What European banking supervision has done, though, is help reduce uncertainty about the quality of banks’ assets, the asset quality review of 2014 being a first step towards that goal. In addition, it has made it a priority to address banks’ NPL portfolios. Supervisors can also ensure that supervisory processes related to mergers are effective. On the regulatory side, it is important to ensure faithful and consistent implementation of agreed reforms, including Basel III, as well as to take further steps towards completing the banking union, most importantly the European deposit insurance scheme. All these elements will contribute to reducing uncertainty.

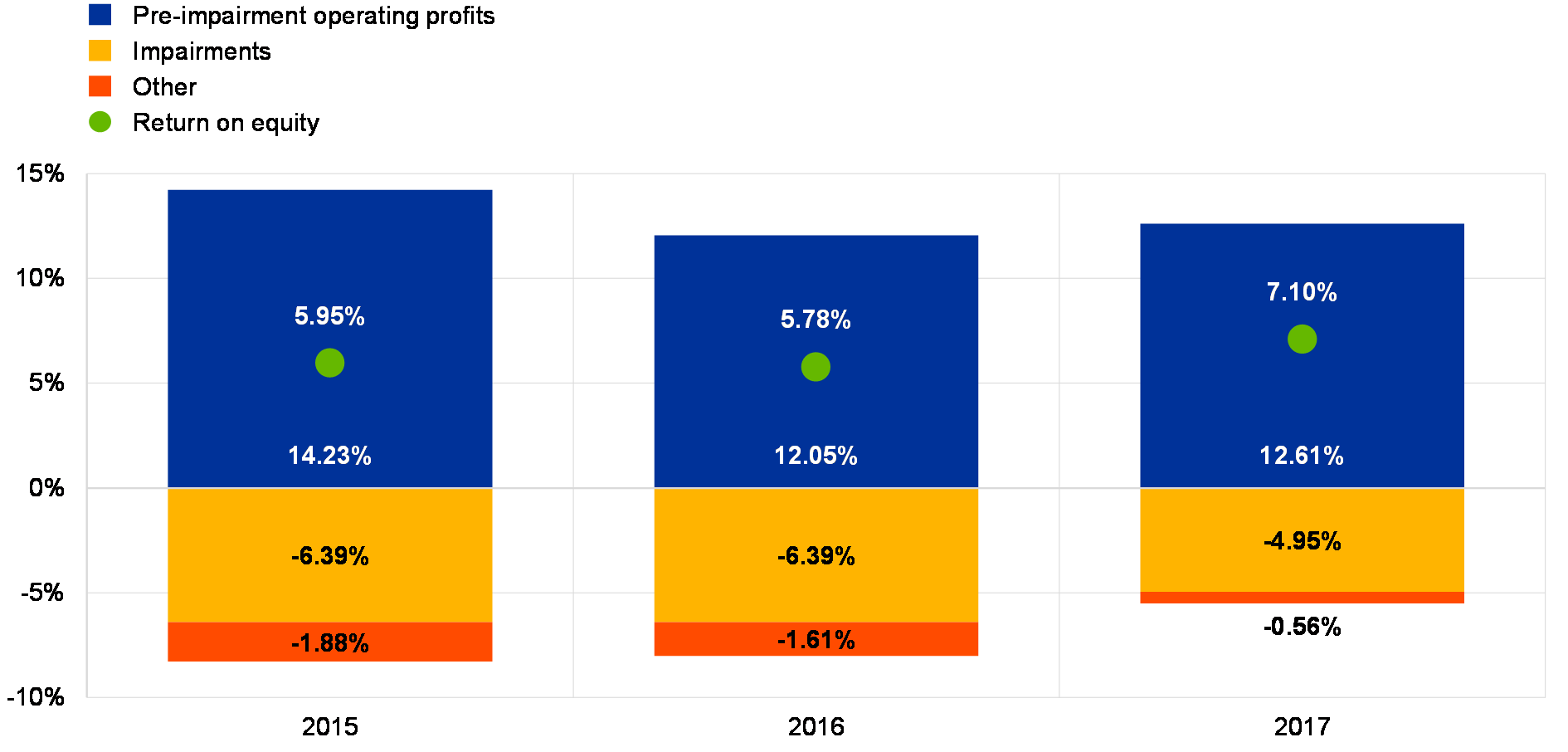

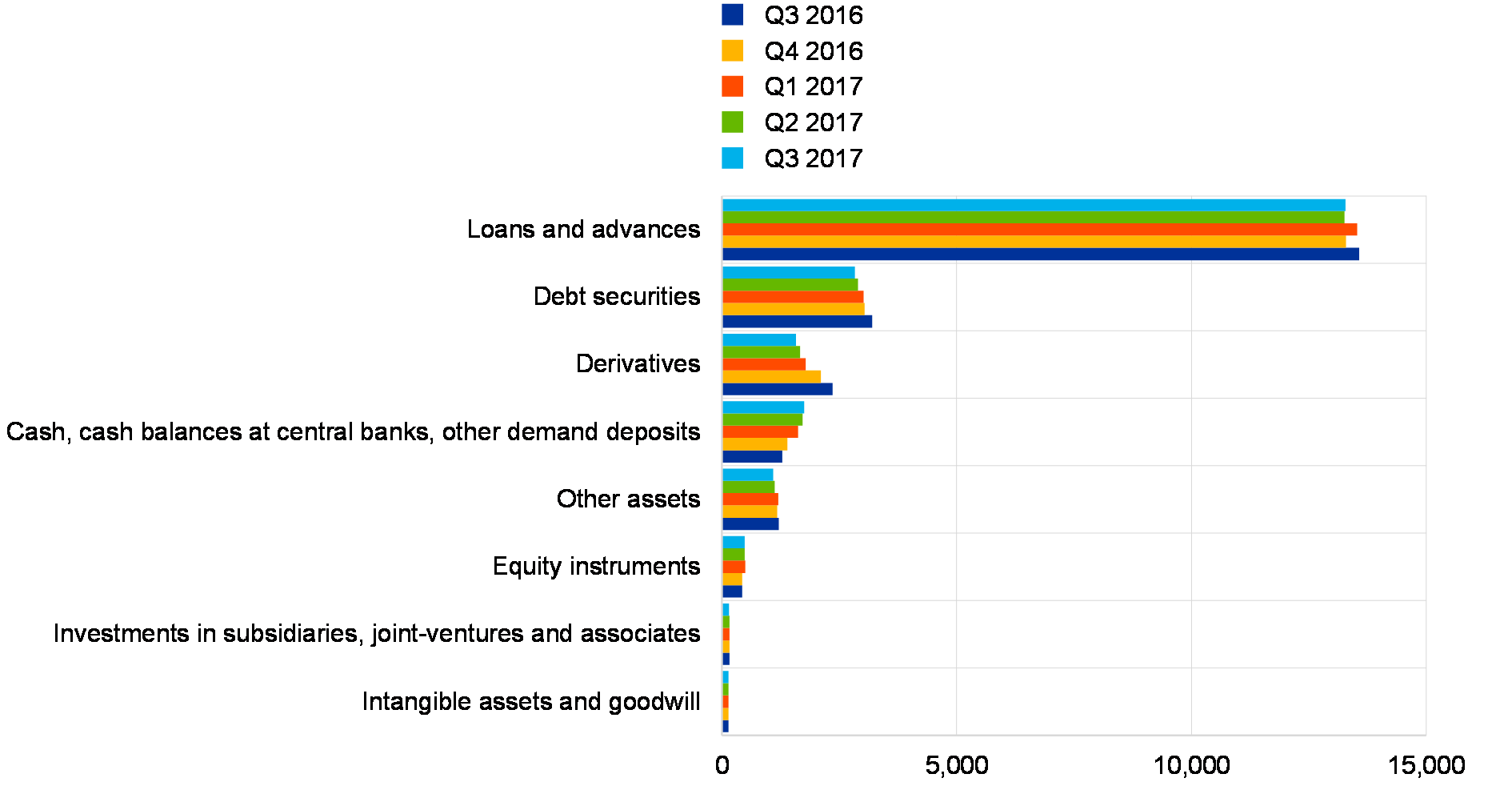

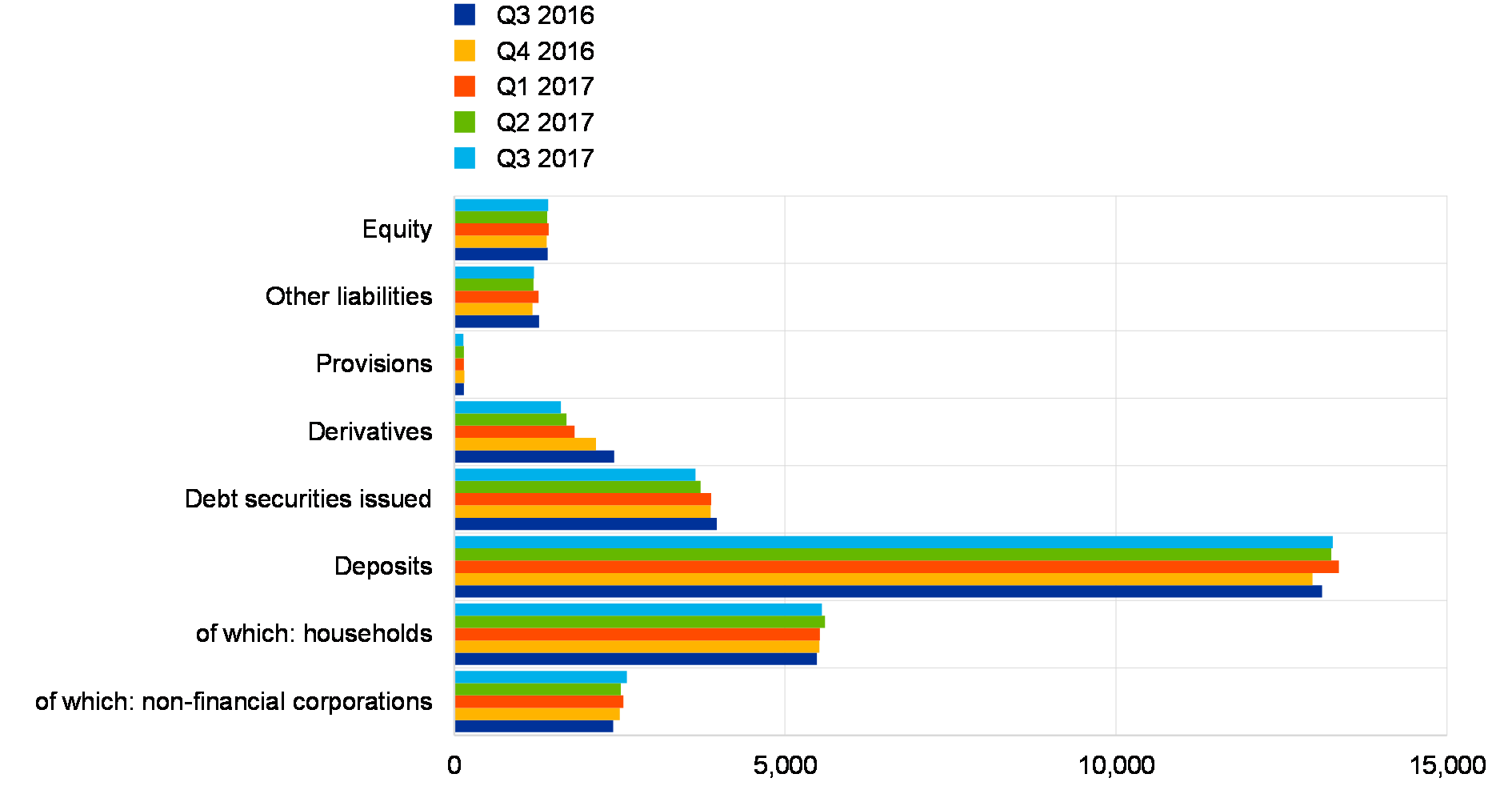

General performance of significant banks in 2017

While 2016 was a particularly difficult year for euro area banks, the situation improved somewhat in 2017. In the first three quarters of 2016, the pre-impairment operating profits of SIs plunged by 10% compared with the first three quarters of 2015. The first nine months of 2017 then saw a recovery in pre-impairment operating profits (+2%). Coupled with a strong decline in impairments (-14.9% compared with 2016, -35.2% compared with 2015) this led to a relative improvement in the annualised return on equity for SIs, which averaged at 7.0% compared with 5.4% in 2016 and 5.7% in 2015.

However, the overall improvement masks considerable differences across banks. Around a dozen banks are still making losses, while a group of about two dozen banks have achieved an average return on equity of around 8% or above over the past three years. Nevertheless, the fact that many publicly listed banks still trade at price-to-book ratios below one indicates a need for further improvements in order to meet investors’ expectations.

The improvement in pre-impairment operating profits was driven by an increase in net fee and commission income of 3.2%, and in net trading income, which increased by 62% compared with the first three quarters of 2016. Net interest income, by contrast, continued to decline and was 1.9% below the value recorded in the first three quarters of 2016, after already dropping by 0.9% from the first three quarters of 2015.

Chart 4

Higher return on equity in 2017 thanks to greater operating profits and lower impairments

(All items are displayed as percentages of equity)

Source: ECB Supervisory Banking Statistics.

Note: Data for all years are shown as second quarter cumulated figures, annualised.

The decrease in net interest income from the third quarter of 2015 to the third quarter of 2016 seemed to be driven by a decline in margins, as loan volumes increased by 4.7%. By contrast, loan volumes decreased by 2.1% between the third quarter of 2016 and the third quarter of 2017, in particular loans to financial institutions (loans to credit institutions -11.8%, loans to other financial corporations -7.3%). It is worth noting that, despite this negative trend, roughly half of SIs have managed to improve their net interest income.

The positive results of banks in the first three quarters of 2017 were helped by lower operating expenses, which are at their lowest since 2015. They dropped by 2.3% with respect to the first nine months of 2016 (-1.6% compared with the first nine months of 2015), most likely thanks to the restructuring measures recently taken by several euro area banks.

1.2 Work on non-performing loans (NPLs)

The situation across Europe

Levels of non-performing loans have come down since 2015 but are still unsustainable

Non-performing loans (NPLs) on SIs’ balance sheets stood at almost €760 billion in the third quarter of 2017, down from €1 trillion in early 2015. However, there are parts of the banking sector where NPL levels remain far too high. Clearly, NPLs are a sizeable problem for the European banking sector. This is because NPLs weigh on the balance sheets of banks, drag down profits, divert resources from more productive uses, and keep banks from lending to the economy. It is therefore necessary for banks to address NPLs. Work on NPLs was one of ECB Banking Supervision’s most important supervisory priorities in 2017. The ongoing project is coordinated by a high-level group on NPLs, which reports directly to the ECB’s Supervisory Board. The group’s main objective is to develop an efficient and consistent supervisory approach with regard to banks with high levels of NPLs.

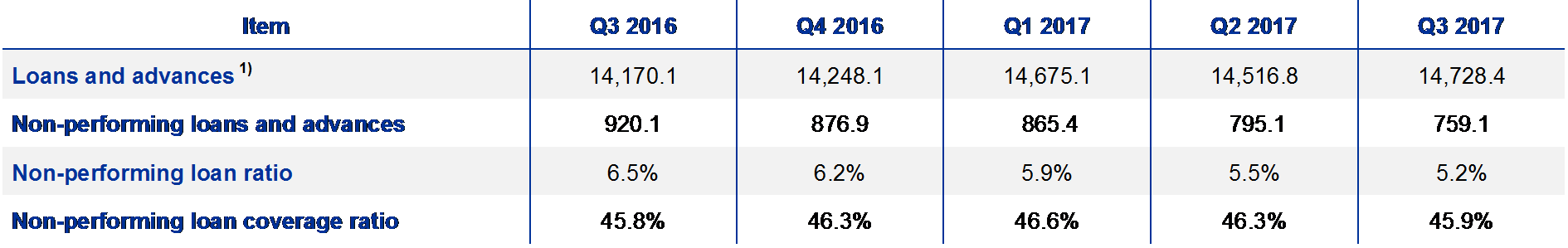

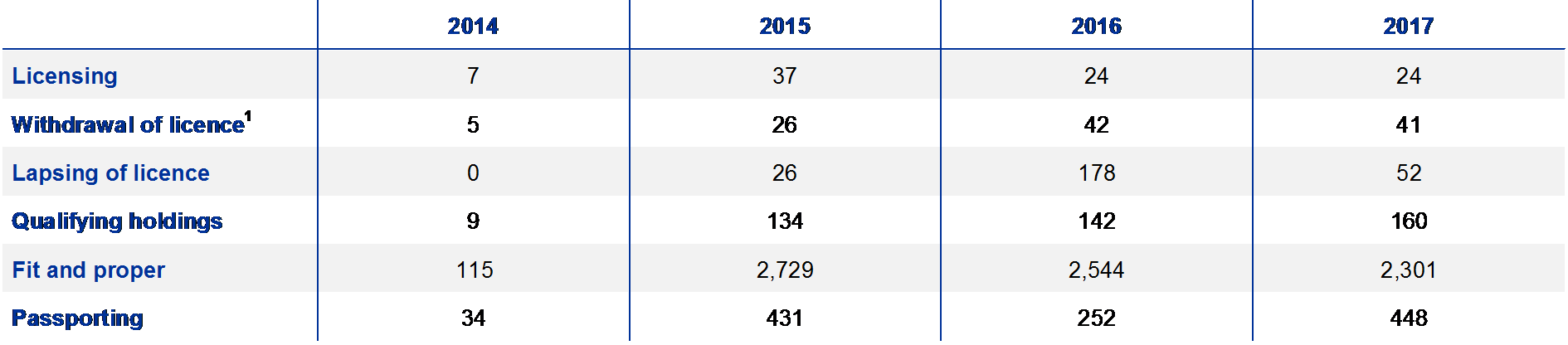

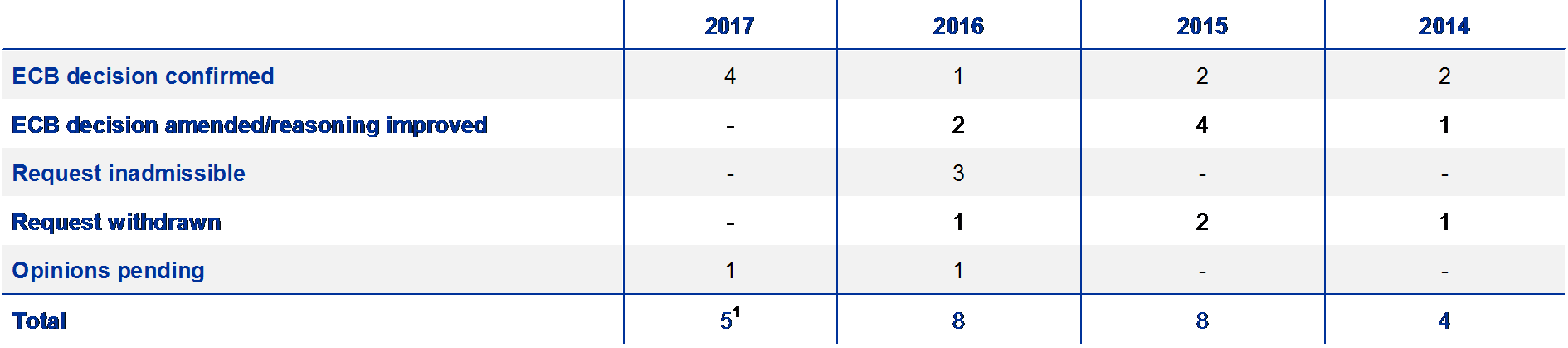

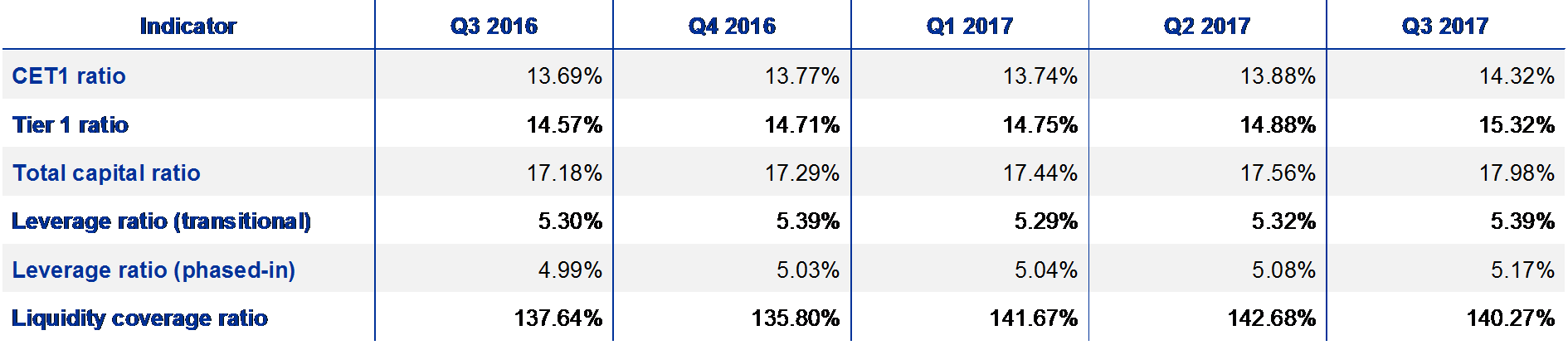

The ECB publishes its Supervisory Banking Statistics[6] on a quarterly basis, including data on asset quality for SIs. Table 1 shows the decrease in NPL levels between 2016 and 2017.

Table 1

Non-performing loans and advances – amounts and ratios by reference period

(EUR billions; percentages)

Source: ECB.

Notes: SIs at the highest level of consolidation for which common reporting on capital adequacy (COREP) and financial reporting (FINREP) are available. Specifically, there were 124 SIs in the second quarter of 2016, 122 in the third quarter of 2016, 121 in the fourth quarter of 2016, 118 in the first quarter of 2017 and 114 in the second quarter of 2017. The number of entities per reference period reflects changes resulting from amendments to the list of SIs following assessments by ECB Banking Supervision, which generally occur on an annual basis, and mergers and acquisitions.

1) Loans and advances in the asset quality tables are displayed at gross carrying amount. In line with FINREP: (i) held for trading exposures are excluded, (ii) cash balances at central banks and other demand deposits are included. In accordance with the EBA definition, non-performing loans are loans and advances other than held for trading that satisfy either or both of the following criteria: (a) material loans which are more than 90 days past due; (b) the debtor is assessed as unlikely to pay its credit obligations in full without realisation of collateral, regardless of the existence of any past-due amount or of the number of days past due. The coverage ratio is the ratio between accumulated impairments on loans and advances and the stock of NPLs.

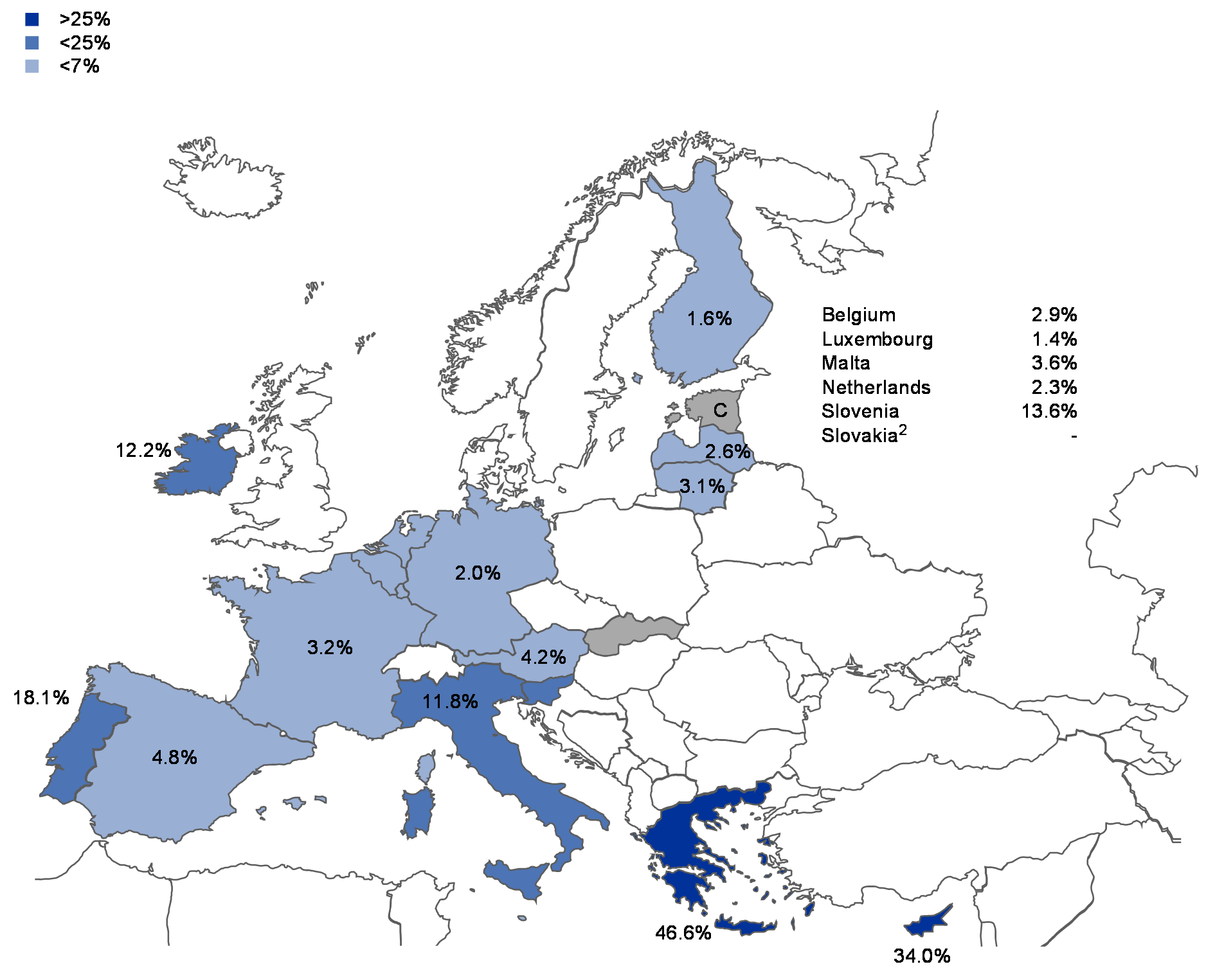

NPL ratios vary markedly across the euro area

Looking across the euro area, the NPL ratio continues to differ significantly from country to country, as shown in Figure 2. In the second quarter of 2017, Greek and Cypriot SIs had the highest NPL ratios (with country-weighted averages standing at 46.6% and 34.0% respectively). With 18.1%, Portuguese SIs had the third highest NPL ratio. Looking at the trend, the NPL ratio decreased significantly year-on-year for SIs in Cyprus (-6.3 pp), Ireland (-5.6 pp), Italy (-4.4 pp) and Slovenia (-3.2 pp). In the third quarter of 2017, the stock of NPLs for Italian SIs was €196 billion, followed by French SIs (€138 billion), Spanish SIs (€112 billion), and Greek SIs (€106 billion).

Figure 2

Non-performing loans and advances1 – ratios by country, reference period Q2 2017

Source: ECB.

Notes: SIs at the highest level of consolidation for which common reporting (COREP) and financial reporting (FINREP) are available.

C: the value is not included for confidentiality reasons.

1) Loans and advances in the asset quality tables are displayed at gross carrying amount. In line with FINREP: (i) held for trading exposures are excluded, (ii) cash balances at central banks and other demand deposits are included.

2) There are no SIs at the highest level of consolidation in Slovakia.

Some FINREP are net of NPL transfers, which are ongoing and expected to be finalised shortly.

The need for a comprehensive strategy for resolving NPLs

The need for a strategy was identified in three main areas: (i) supervisory actions, (ii) legal and judicial reforms, and (iii) secondary markets for NPLs

ECB Banking Supervision highlighted at an early stage that a joint effort from all stakeholders was needed to resolve NPLs. This was also one of the main findings of the ECB’s NPL stocktake report on national practices, the latest version of which was published in June 2017 (see Section 1.2.3.1). This report referred to the need for a comprehensive European strategy in three key areas: (i) supervisory actions, (ii) legal and judicial reforms, and (iii) the need to develop secondary markets for distressed assets.

Figure 3

A comprehensive strategy to address NPLs requires action from all stakeholders, including EU and national public authorities

Regarding supervisory actions, ECB Banking Supervision has implemented a comprehensive supervisory framework for NPLs, which includes:

- publishing guidance to all SIs, outlining supervisory expectations with regard to managing and reducing NPLs;

- developing quantitative supervisory expectations to foster timely provisioning practices in the future;

- conducting regular on-site inspections with a focus on NPLs;

- collecting additional relevant data from banks with high levels of NPLs.

Following the 11 July 2017 ECOFIN conclusions on an action plan to tackle non-performing loans in Europe, ECB Banking Supervision is also supporting the European Banking Authority (EBA) in issuing general guidelines on NPL management which are consistent for all banks in the EU. Moreover, ECB Banking Supervision is interacting with the EBA on promoting the enhancement of underwriting standards for new loans.

More generally, ECB Banking Supervision has been actively contributing to numerous other NPL initiatives in the three areas mentioned above, including those which are part of the EU action plan (as agreed by the EU Council in July 2017), closely collaborating with the stakeholders in charge of the initiatives.

Key elements of the supervisory approach to NPLs

Stocktake of national practices

An analysis of current supervisory and regulatory practices as well as obstacles relating to the workout of NPLs was carried out

In June 2017 the ECB published its latest stocktake of national supervisory practices and legal frameworks related to NPLs. This report presents analyses of practices across all 19 euro area countries as at December 2016.[7] In addition to identifying best supervisory practices, its purpose was to identify (i) current regulatory and supervisory practices, and (ii) obstacles related to the workout of NPLs. This updated and extended stocktake builds upon a previous stocktake of national supervisory practices and legal frameworks related to NPLs. That stocktake covered eight euro area countries (Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Germany) and was published in September 2016. It focused on identifying best practices in jurisdictions with relatively high levels of NPLs, or a “sectoral” NPL issue, and existing frameworks for managing NPLs.[8]

One of the key lessons: all stakeholders need to be prepared in order to manage legal aspects in a timely and efficient manner

The 2017 stocktake shows that, across the euro area, some progress has been made in addressing the NPL issue from a supervisory perspective. The stocktake, combined with experience from jurisdictions with high NPL levels, reveals one key lesson: there is a need for all stakeholders to be proactive and prepared before NPL levels get too high. Many countries with low levels of NPLs have not amended their relevant legal frameworks since the beginning of the crisis. All in all, they should be better prepared to timely and effectively manage the legal aspects that might arise from a potential future increase in NPL levels. This means, for instance, speeding up out-of-court mechanisms (e.g. in enforcing collateral or processing corporate and household insolvency claims).

Regarding the supervisory regime and practices for addressing NPLs, the stocktake illustrates that tools such as specifically focused on-site inspections of arrears and NPL management play a decisive role in detecting emerging issues at an early stage. In this respect, the ECB’s Guidance to banks on NPLs, which is applicable to all SIs, is an important element of supervisory assessment going forward (see Section 1.1.2).

With respect to less significant institutions (LSIs), euro area countries generally still lacked specific guidance on NPLs when the stocktake of national practices was published. However, a number of NCAs have indicated that they are considering whether to apply the ECB’s guidance on NPLs to LSIs as well. Furthermore, in its conclusions of July 2017 the EU Council asked the EBA to issue, by summer 2018, general guidelines on NPL management, consistent with the aforementioned guidance, with an expanded scope applying to all banks in the entire EU.

With regard to the legal frameworks, the stocktake shows that these have (with some exceptions) improved only incrementally in countries with high stocks of NPLs since the first stocktake. In any case, it is too early to assess the effectiveness of these changes. With regard to judicial systems (including the recruitment of insolvency experts), changes are not keeping pace with legislative developments.

As to information frameworks for NPLs, the stocktake shows that most euro area countries have central credit registers in place, which are usually managed by national central banks. Such registers are generally considered to be a valuable supervisory tool for on-site and off-site analyses as well as for the sharing of information between banks.

NPL guidance and related follow-up

The publication of NPL guidance to banks was an important step in tackling the NPL issue across the euro area

ECB Banking Supervision published qualitative guidance to banks on how to deal with non-performing loans[9] (hereafter referred to as the “NPL guidance”) in March 2017. The publication was preceded by a public consultation, which ran from 12 September 2016 to 15 November 2016. A public hearing was held on 7 November 2016. More than 700 individual comments were received and assessed during the consultation. The development of the NPL guidance was an important step towards a significant reduction of NPLs in the euro area.

Aim and content of the NPL guidance

NPL guidance outlines supervisory expectations for each stage of the life cycle of NPL management

The key policy message of the NPL guidance is that the banks concerned should address high levels of NPLs as a matter of priority and in a comprehensive manner, by focusing on their internal governance and setting out their own operational plans and quantitative targets. All three elements will be scrutinised by the relevant JSTs. The “wait and see” approach we have often seen in the past cannot continue. Banks’ own targets need to be adequately embedded in incentive schemes for managers and must be closely monitored by their management bodies.

The NPL guidance is a practical document which sets out supervisory expectations on all the relevant areas that a bank should address when dealing with NPLs. It is based on the EBA’s common definition of non-performing exposures[10]. However, it also covers aspects of foreclosed assets and performing exposures with a high risk of turning non-performing, including “watch-list” exposures and performing forborne exposures.

The NPL guidance was developed on the basis of the existing best practices of several euro area countries. Its structure follows the life cycle of NPL management, outlining related supervisory expectations on NPL strategies, NPL governance and operations, forbearance treatments, NPL recognition, NPL provisioning and write-off and collateral valuations.

Follow-up work on NPL and foreclosed asset strategies

Banks with high NPL ratios submitted their NPL reduction strategies and operational plans to the ECB for assessment

Following the publication of the NPL guidance, SIs with high NPL ratios were asked to submit their strategies and operational plans for reducing NPLs to ECB Banking Supervision. To ensure comparable information and a level playing field, a specific template was devised for banks to fill in. Using that template, banks had to demonstrate, at portfolio-level, how and over what period of time they planned to reduce their NPLs and foreclosed assets.

From March to June 2017, the banks submitted their strategies, and ECB Banking Supervision assessed them against its supervisory expectations. The assessment was carried out by JSTs on a bank-by-bank basis with the support of a horizontal NPL team. Throughout the process the JSTs met with their banks to discuss the strategies.

While NPL strategies, operational plans and quantitative targets are the responsibility of each individual bank, ECB Banking Supervision expects them to be ambitious and credible in order to ensure that the reduction of NPLs and foreclosed assets is both timely and sufficient.

Assessment of the NPL strategies

Strategies must be ambitious and credible, and supporting governance frameworks fit for purpose

In line with the NPL guidance, a bank’s governance framework should ensure that the NPL strategy can be smoothly executed. Against this backdrop, the JSTs assess the strategies bank-by-bank, focusing on three core building blocks: (i) level of ambition, (ii) the credibility of the strategy and (iii) governance aspects.

The level of ambition is measured by the gross and net reduction of non-performing exposures and foreclosed assets that a bank expects to achieve over a three-year horizon. For each bank, an appropriate “level of ambition” is defined. This takes into account a number of elements, such as the bank’s financial situation, its risk profile, the characteristics of its non-performing portfolio, and the macroeconomic environment. ECB Banking Supervision carried out both country-level and peer benchmarking analyses of the ambition levels projected by the banks with high NPL ratios.

In assessing whether the banks’ strategies are credible, ECB Banking Supervision uses a wide range of analyses to determine whether their projected ambition levels match what they can achieve. The relevant indicators include: capital capacity, provisioning coverage and trends, the materiality of “asset-based” strategies, vintage analysis, assumptions about inflows and outflows to and from the non-performing portfolio, cash recoveries and resources to support them, timelines and diversification of strategic options.

What is an ambitious and credible NPL strategy?

- Oversight and ownership by management bodies.

- Clear and unambiguous reduction targets, identified in a bottom-up manner by the bank on sufficiently granular segments.

- A detailed capital, RWA and provisioning impact assessment of the individual elements of the reduction strategy with detailed rationale to support the execution of the strategy and targets.

- Diversification across a variety of strategic options with a strong focus on vintages greater than two years past due.

- Strong strategic governance, including well-defined staff incentives at senior and operational level, to effectively drive through NPL reduction targets at all stages of the NPL resolution chain.

- Robust internal operational capacities and frameworks to deliver effective NPL reduction, including the ability to engage with borrowers early to reduce the level of exposures which turn non-performing.

- If applicable to a bank, a strong focus on the timely sale of foreclosed assets or on increased provisioning if sales are not carried out in the short term.

- A detailed operational plan setting out the key deliverables, milestones, actions and timelines which are required in order to execute the strategy successfully.

- A strong focus on sound forbearance, i.e. identifying sustainable borrowers and providing them with viable restructuring options to return their loans to performing.

- A well-developed forbearance toolkit, monitored for effectiveness on a granular level.

- A granular monitoring framework for the implementation of the strategy, which allows under-/over-performance drivers to be identified.

The assessment of governance focuses on a wide range of areas, which include: (i) banks’ self-assessment processes; (ii) the level of oversight and monitoring of the strategic plan by the management body; (iii) the incentive schemes in place to promote the execution of the strategy; (iv) the ways in which the strategy is embedded into day-to-day operations; (v) the level of resources (both internal and external) allocated by the bank to work out the loans; and (vi) the strategies underlying operational plans.

Quantitative supervisory expectations on timely provisioning

The draft addendum to the NPL guidance outlines supervisory expectations regarding the levels and timing of prudential provisioning and will be applied on a bank-by-bank basis

In line with its mandate, the ECB needs to apply a forward-looking approach to proactively address risks. Since the publication of the NPL guidance, and also learning from past experience, ECB Banking Supervision has continued working on further measures to address NPLs. On 4 October 2017, it published a draft addendum to the NPL guidance for consultation. This addendum seeks to foster more timely provisioning practices for new NPLs in order to avoid NPLs piling up in the future. During the public consultation, which ended on 8 December 2017, ECB Banking Supervision received 458 individual comments from 36 counterparties. This represents valuable feedback, which was carefully assessed when finalising the document.

The supervisory expectations will improve supervisory convergence and ensure a level playing field. Naturally, the expectations are subject to a case-by-case assessment. In this context, the general supervisory expectation outlined in the addendum is that for unsecured loans, 100%-coverage should be reached two years after a loan has been classified as non-performing. For secured loans, the corresponding time frame is seven years. To avoid cliff edge effects, a suitably gradual path towards those supervisory expectations is important, starting from the moment of NPE classification.

The level of prudential provisions is assessed in the context of the normal supervisory dialogue. As a starting point, the supervisor determines whether a bank’s accounting allowances adequately cover its expected credit risk losses. The accounting allowances are then compared against the supervisory expectations set out in the addendum.

More precisely, during the supervisory dialogue the ECB will discuss with banks any divergences from prudential provisioning expectations. The ECB will then consider the deviations on a bank-by-bank basis and decide, after a thorough analysis that might include deep dives, on-site examinations or both, whether a bank-specific supervisory measure is needed. There is no automaticity in this process. These supervisory expectations, unlike Pillar 1 rules, are not binding requirements which trigger automatic actions.

On-site inspections of NPLs

In the course of 2017, 57 credit risk inspections were completed, of which six were led by the ECB and 51 by NCAs. The management and valuation of NPLs was a key topic in these inspections, addressed in 54 out of the 57 on-site inspection reports. In this context, the main aspects of the work were the assessment of NPL strategies, policies and procedures (54 reports) and a quantitative impact assessment (37 reports).

NPL strategies, policies and procedures

Using the NPL guidance as a benchmark, the most significant shortcomings in NPL strategies, policies and procedures have been identified as follows.

Despite improving NPL governance, deficiencies in NPL recognition remain a concern, especially for forborne NPLs

NPL strategy and governance: in this area, a trend towards more active NPL management has been observed. This is mostly a result of banks’ attempts to meet the supervisory expectations set out in the NPL guidance. However, most of the on-site inspection reports highlight that the information provided to banks’ management bodies is still not granular enough. This affects, for instance, early warning risks and risks that were incurred in different entities of the banking group or that arise from the application of certain restructuring models.

For existing NPLs, findings relate to the adequacy of loan loss provisions and the use of sufficient collateral haircuts and discount times

NPL forbearance: most banks have been found lacking in efficient forbearance policies, be it at the point of entry to or the point of exit from forbearance status. At entry, the criterion of viable versus distressed restructuring is not precisely defined and certain forbearance measures referred to in the NPL guidance are not recognised as such (e.g. granting of additional facilities, request for additional securities/collateral). At the same time, classic forbearance measures (interest rate reduction, term extension) often do not trigger an NPL status in reporting on clients facing financial difficulties. The rules for identifying financial difficulties remain very heterogeneous and too restrictive, mostly owing to insufficient data. Forbearance exit criteria, especially with regard to forbearance during the probation period, are insufficiently monitored.

NPL recognition/classification: most of the findings concerned (i) insufficient unlikely-to-pay criteria, concerning, notably, specific sectors (shipping, commercial real estate, oil and gas) or financing techniques (leveraged finance) and (ii) undue reliance solely on the backstop criteria explicitly mentioned in the CRR.

NPL provisioning and collateral valuation: although provisioning processes are increasingly being supported by IT tools and more precise policies, the main areas for further improvement are unrealistic collateral valuations (sometimes indexed upwards instead of revalued), overly optimistic collateral haircuts and recovery times. Besides, certain banks still have inappropriate practices with regard to the treatment of accrued but not yet paid interest.

NPL data integrity: the many findings in this area include a lack of risk data aggregation processes, for data relevant to the detection of financial difficulties (e.g. data from income statements, EBITDA, DSCR). Furthermore, key parameters (e.g. collateral haircuts, discount times, cure rates) are often significantly misestimated and the criteria for write-offs (e.g. expressed as time in default) are in many cases not clearly defined.

Quantitative assessment

Following inspections, significant quantitative adjustments have been requested – largely to make up for shortcomings in provisions

In addition to assessing policies and procedures as usual, the on-site inspection teams reviewed extensive samples of credit files. In this context, statistical techniques were sometimes used to evaluate parts of the loan book in order to verify whether the level of provisions was sufficiently compliant with prudential requirements (Article 24 of the CRR, and Article 74 of CRD IV transposed into national legislation) and international accounting standards (notably IAS 39 and IAS 8). While the majority of these reviews resulted in either no significant change or by and large bearable adjustments, some of the on-site inspections did identify cases of very significant quantitative shortcomings that triggered individual supervisory actions.

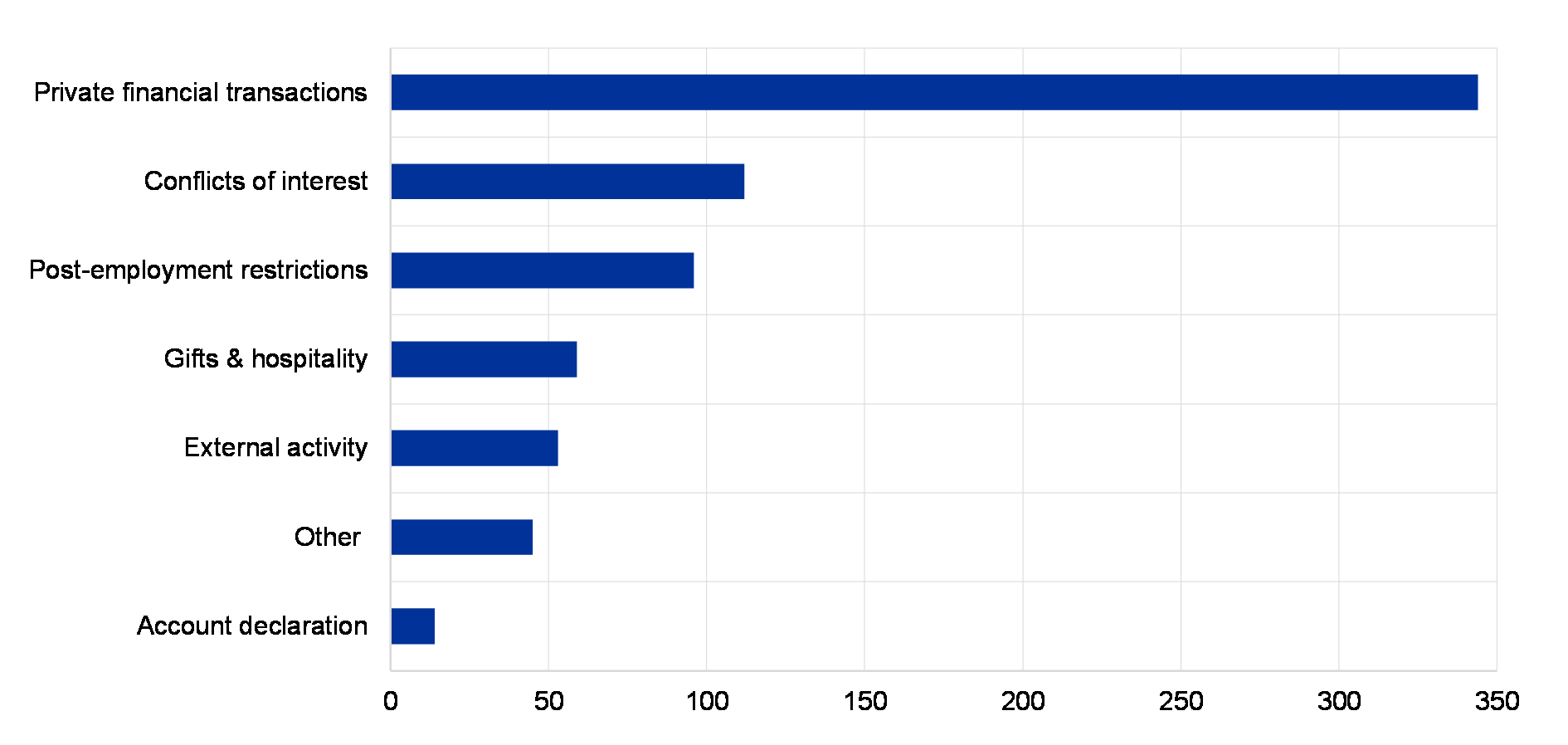

ECB quarterly data collection for high-NPL banks

Additional quarterly data collection has been introduced for SIs with material NPL exposures

In September 2016 the ECB’s Supervisory Board approved the launch of a quarterly collection of data on NPLs for SIs with material NPL exposures (“high-NPL banks”).[11] The objective is to supplement the information collected by the supervisors under the harmonised reporting framework (EBA ITS on Supervisory Reporting) with additional and more granular data. Such data are necessary to efficiently monitor the NPL-related risks of high-NPL banks.

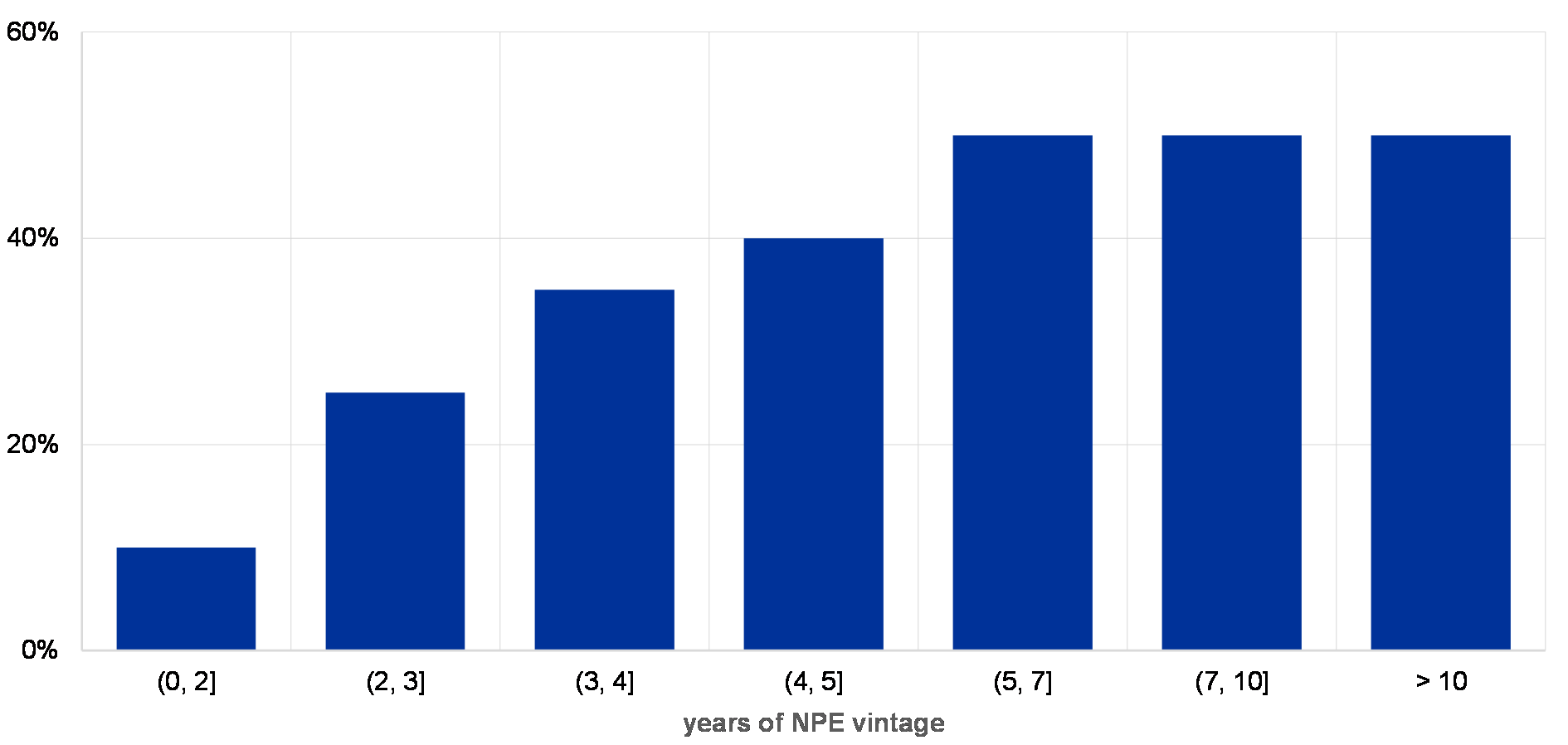

The ECB reporting templates used throughout the 2017 reporting cycle[12] complement the existing FINREP templates for non-performing and forborne exposures. They include, among other things, a breakdown of the stock of NPLs by vintage as well as information on collateral (also comprising foreclosed assets), NPL inflows and outflows and restructuring/forbearance data.

The data from the quarterly collection are benchmarked and inputted by the Joint Supervisory Teams into the assessment of banks’ strategies, procedures and organisation with regard to NPL management. The example below shows non-performing exposures in respect of which court proceedings had been started as a percentage of the reporting sample of high-NPL banks as at end-June 2017.

Chart 5

Share of NPLs for which court proceedings have been started; sorted by years of vintage

(percentages)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Based on a sample of high-NPL banks, covering ~50% of all SI NPL volume. Data rounded.

Banks participating in this data collection have been informed of the relevant requirements in their respective SREP letters.[13]

Leveraging on the experience gained during the 2017 reporting cycle, the ECB has amended and streamlined the set of templates used for the quarterly data collection and has provided the reporting institutions with a revised version of the requirements, which will be applicable from 31 March 2018.

The ECB and the EBA are currently discussing the possibility of including those NPL templates into the harmonised reporting framework.

Outlook and next steps

It is an ongoing key supervisory priority for ECB Banking Supervision to continue its efforts to resolve the NPL issue across SIs. The JSTs will continue their close interaction with high-NPL banks, in particular focusing on their strategies to resolve NPLs. These strategies are expected to be closely monitored and updated at least annually.

The final addendum to the NPL guidance was published on 15 March 2018. However, since the addendum focuses on new NPLs, any related follow-up activities with the SIs will only start gradually over time.

Finally, given that many stakeholders are required to act on the issue of NPLs, ECB Banking Supervision will continue to collaborate closely with other European and national stakeholders to address the remaining issues in the NPL-related framework, as outlined in its stocktake report published in June 2017.

1.3 Work on thematic reviews

Business models and profitability drivers

In 2016 European banking supervision launched a thematic review in order to assess the business models and profitability drivers of the majority of SIs in depth. This thematic review will be concluded in 2018.

Assessing banks’ business models and profitability drivers is a key priority for European banking supervision. Profitable banks can generate capital organically and thus build up adequate buffers, while maintaining a reasonable risk appetite and lending to the real economy. Banks that struggle to reach sustainable profitability, on the other hand, may stray into riskier activities.

Profitability has been under pressure from various sources

In the current environment, euro area banks’ profitability is under pressure from low interest rates and continued high impairment flows in some countries and sectors. Moreover, it is also challenged by structural factors, such as overcapacity in some markets, competition from non-banks, increasing customer demand for digital services, and the need to adapt to new regulatory requirements.

The first year of the thematic review was a preparatory phase: tools were developed and guidance for the JSTs devised

The thematic review addresses banks’ profitability drivers both at firm level and across business models. In doing so, it pursues several objectives. Besides assessing banks’ ability to mitigate weaknesses in their business models, it assesses how weak profitability impacts banks’ behaviour. It will also enrich horizontal analysis, in particular by pooling the insights gained by the JSTs and harmonising their follow-up across banks. During the first year of the thematic review, the necessary analytical tools were created and comprehensive guidance to support the JSTs in their analysis was devised.

In the first quarter of 2017, the ECB collected data on banks’ forecasted profit and loss results as well as the assumptions underlying them. In aggregate, over the next two years, banks expect a gradual improvement in profitability on the back of solid loan growth and lower impairments, while net interest margins will remain under pressure.

In the second year of the thematic review, the JSTs analysed their banks’ business models and profitability drivers

During the second and third quarter of 2017, the focus of the thematic review shifted to bank-specific analyses, which were performed by the JSTs. The teams interacted directly with the banks in order to screen all aspects of their business models and profitability drivers. The aspects examined ranged from the banks’ core capacity to generate revenues to their ability to understand and steer their activities and implement their chosen strategies.

The findings of the JSTs are being combined with analytical results from the ECB’s DG Microprudential Supervision IV, leveraging on internal and external data sources. This includes a thorough analysis of the most profitable banks to understand the drivers of their performance and ascertain whether these are sustainable. Banks’ strategies to address low profitability vary significantly: they include growth strategies to bolster net interest income, expanding fee and commission-related business, cost-cutting and digitalisation.

Deficiencies in the institutions’ internal set-up to steer profitability, as well as issues related to the business plans, such as excessive risk-taking, were brought to the banks’ attention as part of the supervisory dialogue. The identification of deficiencies will also result in risk mitigation plans being drawn up for the affected banks, to be communicated in early 2018.

Ultimately, the results of the thematic review will feed into the 2018 Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) and could trigger on-site inspections as well as deep dives into areas where blind spots have been identified. The analyses will also provide the opportunity to benchmark practices across comparable institutions.

Impact of IFRS 9 on provisioning

IFRS 9 aims to ensure more adequate and timely provisioning practices

The new accounting standard for financial instruments (IFRS 9), which entered into force in January 2018, aims to address the lessons learned from the financial crisis, namely, that provisions based on incurred loss models often resulted in “too little, too late”. Against this backdrop, IFRS 9 was designed to ensure more adequate and timely provisioning by introducing an expected credit loss model that incorporates forward-looking information.

The new features introduced by IFRS 9 constitute a major change in the accounting regime for financial instruments, augmenting the role of judgement in the implementation and subsequent application of the standard. Given that accounting numbers form the basis for calculating prudential capital requirements, the SSM made it one of its supervisory priorities for 2016 and 2017 to (i) assess how well SIs and LSIs are prepared for the introduction of IFRS 9, (ii) gauge the potential impact on provisioning, and (iii) promote consistent application of the new standard. This assessment was mainly based on what are considered best practices at international level, as set out in the guidance issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and the European Banking Authority (EBA). In carrying out this supervisory exercise the ECB collaborated closely with the NCAs, the EBA and the BCBS. This collaboration will continue throughout the follow-up activities planned for 2018.

A transition period will smooth the potential negative impact of IFRS 9 on the regulatory capital of banks

Regarding the impact on prudential figures, it is important to note that the EU co-legislators have adopted transitional measures. These measures aim to smooth the potential negative impact of IFRS 9 on the regulatory capital of banks. The measures have been implemented through Regulation (EU) 2017/2395[14], which was published in the Official Journal on 27 December 2017.

A report with the results of the thematic review has been published on the ECB’s banking supervision website. It provides a summary of the main qualitative and quantitative results for SIs and LSIs. With regard to the qualitative results, the overall conclusion is that, for some institutions, there is still room for improvement if a high-quality implementation of IFRS 9 is to be achieved. Overall, the supervisors have noted that the largest SIs are more advanced in their preparation for the new standard than the smaller SIs. For SIs, the most challenging aspect of IFRS 9 is measuring impairment, as this requires the institutions to significantly change their internal processes and systems. For LSIs, the most challenging aspects are expected credit loss (ECL) modelling and data availability. The thematic review has shown that the vast majority of institutions are working intensively on the implementation of IFRS 9.

The fully loaded average negative impact of IFRS 9 on the CET1 ratio is estimated to be 40 basis points

From a quantitative viewpoint, the report shows that the fully loaded average negative impact of IFRS 9 on the regulatory Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio is estimated to be 40 basis points (bps). This result is based on information provided by SIs which are at an advanced stage in their implementation of IFRS 9 and can thus provide the most reliable data. Likewise, the fully loaded average negative impact on the regulatory CET1 ratio of LSIs is expected to be 59 bps. Taking transitional arrangements into account, the average negative impact of IFRS 9 on CET1 at the transition date is expected to be around 10 bps for SIs and 25 bps for LSIs.[15]

The first phase of the review for the SIs was conducted for those institutions that were ready to be assessed in the first quarter of 2017. Any findings and any need for remedial actions were communicated to the relevant institutions; the JSTs will follow up on outstanding issues throughout 2018.Those institutions that were not fully prepared for the assessment received a warning letter in the first quarter of 2017, and were assessed by the JSTs by 30 November 2017. A horizontal evaluation of the preparedness of a sample of LSIs was performed. The ECB and the NCAs plan to follow up on LSIs’ implementation of IFRS 9 in 2018.

Risk data aggregation and risk reporting

A thematic review on risk data aggregation and risk reporting was one of the SSM’s supervisory priorities for 2016 and 2017

Sound risk management in banks rests on firm-wide data quality and effective risk data aggregation and reporting practices. However, a key lesson from the financial crisis was that some banks were unable to fully identify risk exposures. This was because they lacked adequate risk information and relied on weak risk data aggregation practices. The affected banks’ ability to take timely decisions was seriously damaged, with wide-ranging consequences for the banks themselves and the entire financial sector.

Against this backdrop, a thematic review on risk data aggregation and risk reporting was one of the SSM’s supervisory priorities for 2016 and 2017.

The thematic review started in 2016, covering a sample of 25 SIs. It was performed by the relevant JSTs, supported by a centralised working group comprising ECB and NCA staff. The NCAs provided operational guidance and ensured that it was applied consistently across the sample. The review was carried out in line with the principle of proportionality, taking into account the size, business models and complexity of the banks under review.

The results of the review were communicated to banks and requests for remedial action were made in the second quarter of 2017

The outcome shows that the implementation status of the BCBS 239 principles for the SIs in scope remains unsatisfactory to a considerable degree. The results of the review were communicated to the banks that were part of the sample, in the context of individual supervisory dialogues. Requests for remedial action were included in the final follow-up letters sent by the ECB in the second quarter of 2017. These requests were particularly directed at banks which showed significant weaknesses that might have a major impact on their risk profiles.

In this context, the banks were also requested to submit clear, accurate, and detailed action plans. The centralised working group, supported by the JSTs, assessed these action plans in order to ensure horizontal consistency.

The methodology developed by the centralised working group will enrich the supervisory assessment methodology on risk data aggregation and risk reporting. More generally, for all SIs, the main outcomes of the review will be incorporated into the assessment of data aggregation and reporting capabilities as part of the SREP.

The review was guided by the principles for effective risk data aggregation and risk reporting[16] issued by the BCBS. And as the ECB monitors how institutions’ risk data aggregation and risk reporting capabilities are improving, it regularly informs and updates the BCBS’s Risk Data Network on relevant insights.

Outsourcing

Over the past decade, technological developments have not only changed customers’ expectations regarding banking services. They have also changed the way banks operate and deliver their services. The advent of cloud computing in particular has had a significant impact on how banks structure their business, namely, what they still do “in house” and what they outsource to external service providers.[17] These developments provide banks with new business opportunities and easy access to services and expertise outside of the regular banking realm. However, these opportunities also entail the challenge of managing the associated risks. And, quite naturally, this is something European banking supervision pays close attention to. One of the concerns is that outsourcing could render euro area banks mere shell companies or create obstacles to the effective supervision of banks, for instance in view of Brexit and the potential relocation of banks from the United Kingdom to the euro area.

Outsourcing was identified as one of the SSM’s supervisory priorities for 2017 and a targeted thematic review of banks’ outsourcing management and practices was launched

The ECB is notified of certain outsourcing arrangements where a relevant procedure is provided by the national framework. More generally, determining whether outsourcing arrangements are adequate is part of assessing an institution’s risk profile, including its risk management arrangements for SREP purposes[18]. Against this background, outsourcing was identified as one of the SSM’s supervisory priorities for 2017 and a targeted thematic review of banks’ outsourcing management and practices was launched. The objective of the review is to obtain insights into the policies, strategies and governance arrangements that banks use when dealing with risks from outsourcing, and how they assess and monitor outsourced risks.

As part of the thematic review, a horizontal team, working together with the relevant JSTs, collected information on how a representative sample of significant banks manage the risks associated with outsourced activities. The thematic review found that, under the current set-up, banks’ approaches to outsourcing differ a lot both in terms of governance and monitoring. Banks’ uncertainties with regard to the identification of outsourcing and material outsourcing were also flagged. Furthermore, the team identified best practices and found that further guidance for banks on how to manage outsourced activities is not only necessary from a supervisory point of view, but would also be welcomed by the banks themselves.

Outsourcing developments impact the banking sector worldwide. They are, however – even within the countries covered by European banking supervision – treated very differently under the respective legal frameworks

The thematic review also included a mapping and assessment of the outsourcing landscape across the euro area, including procedural aspects (e.g. notifications and approvals). A comparison of the national regulatory frameworks confirmed that the landscape is very diverse. While SSM countries have transposed the CEBS[19] Guidelines on Outsourcing[20] in one form or another, they differ greatly in how formal and detailed the resulting provisions are. To complete the picture and account for the international character of many SIs, the ECB also exchanged views on supervisory approaches with several supervisors outside the euro area. It sought to better understand those supervisors’ expectations regarding the management of outsourced activities and, on that basis, to level the international playing field.

The review shows a clear need to further flesh out supervisory expectations regarding banks’ outsourcing arrangements. This would provide more clarity to the banks and, at the same time, help to harmonise the supervisory approach to outsourcing. This work will be initiated in close liaison with the NCAs and the EBA.

1.4 On-site supervision

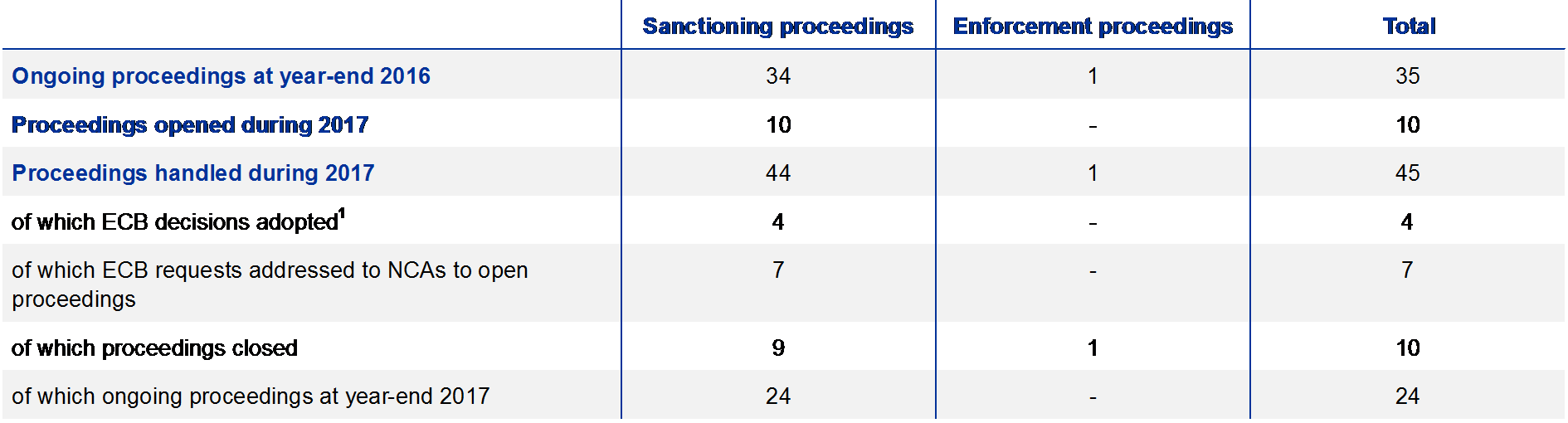

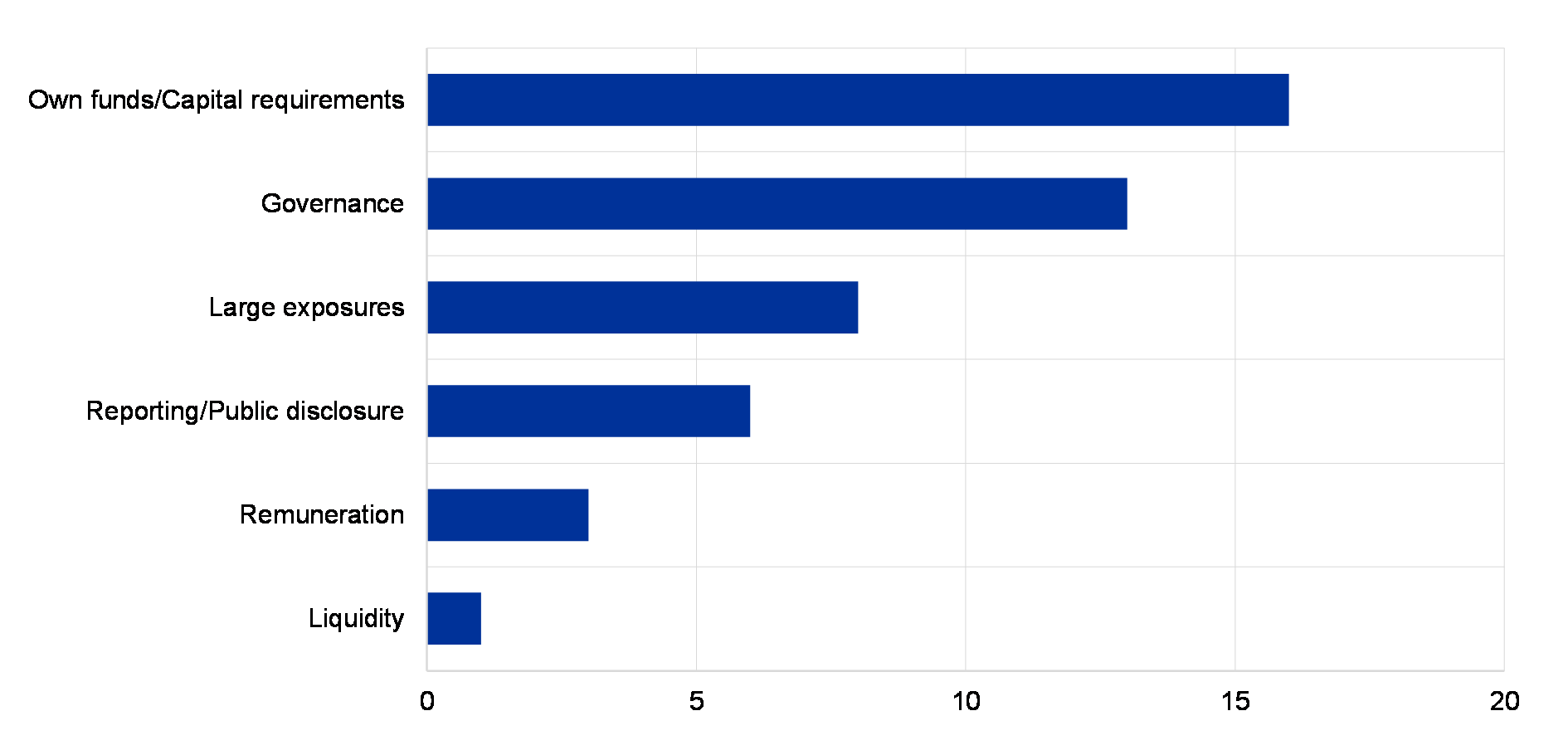

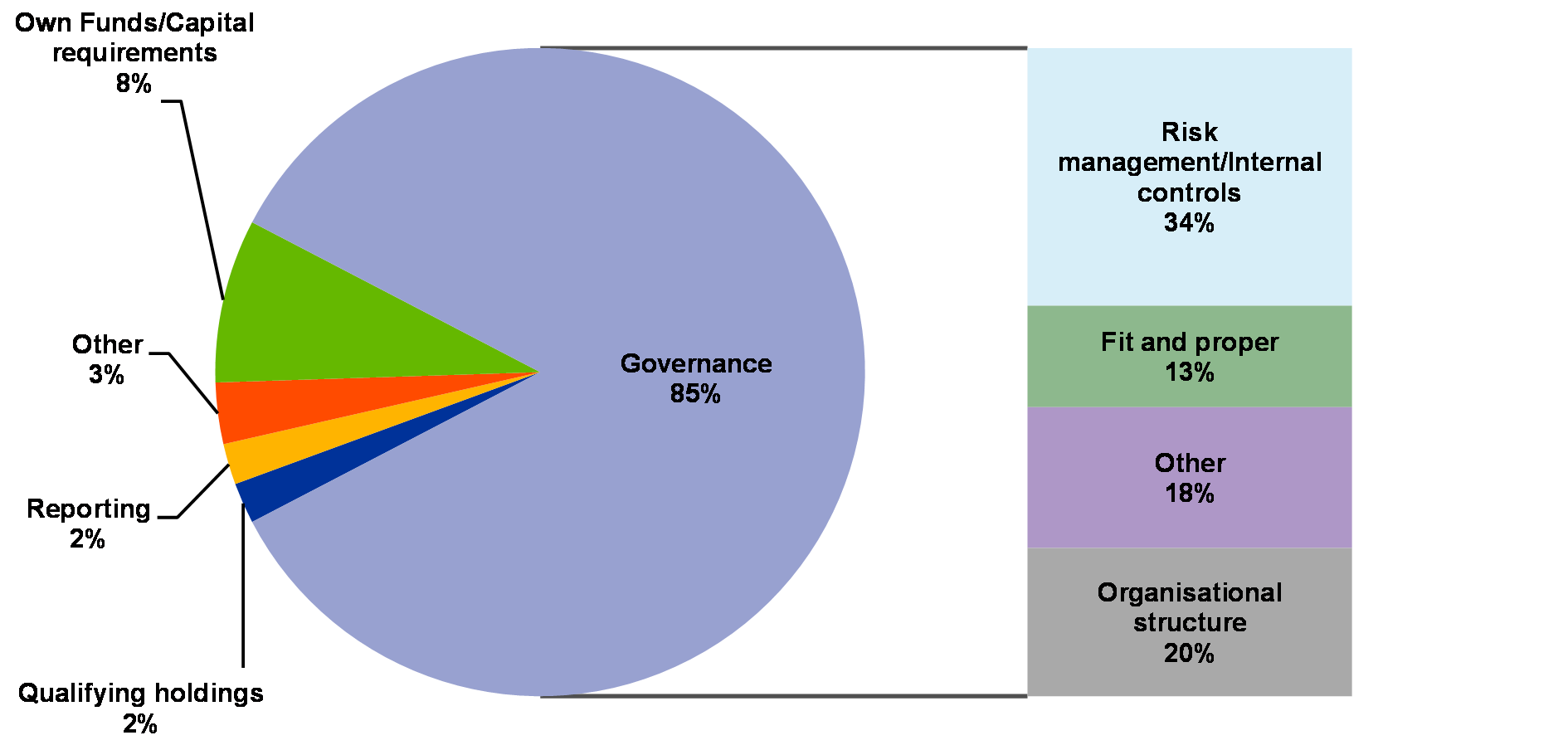

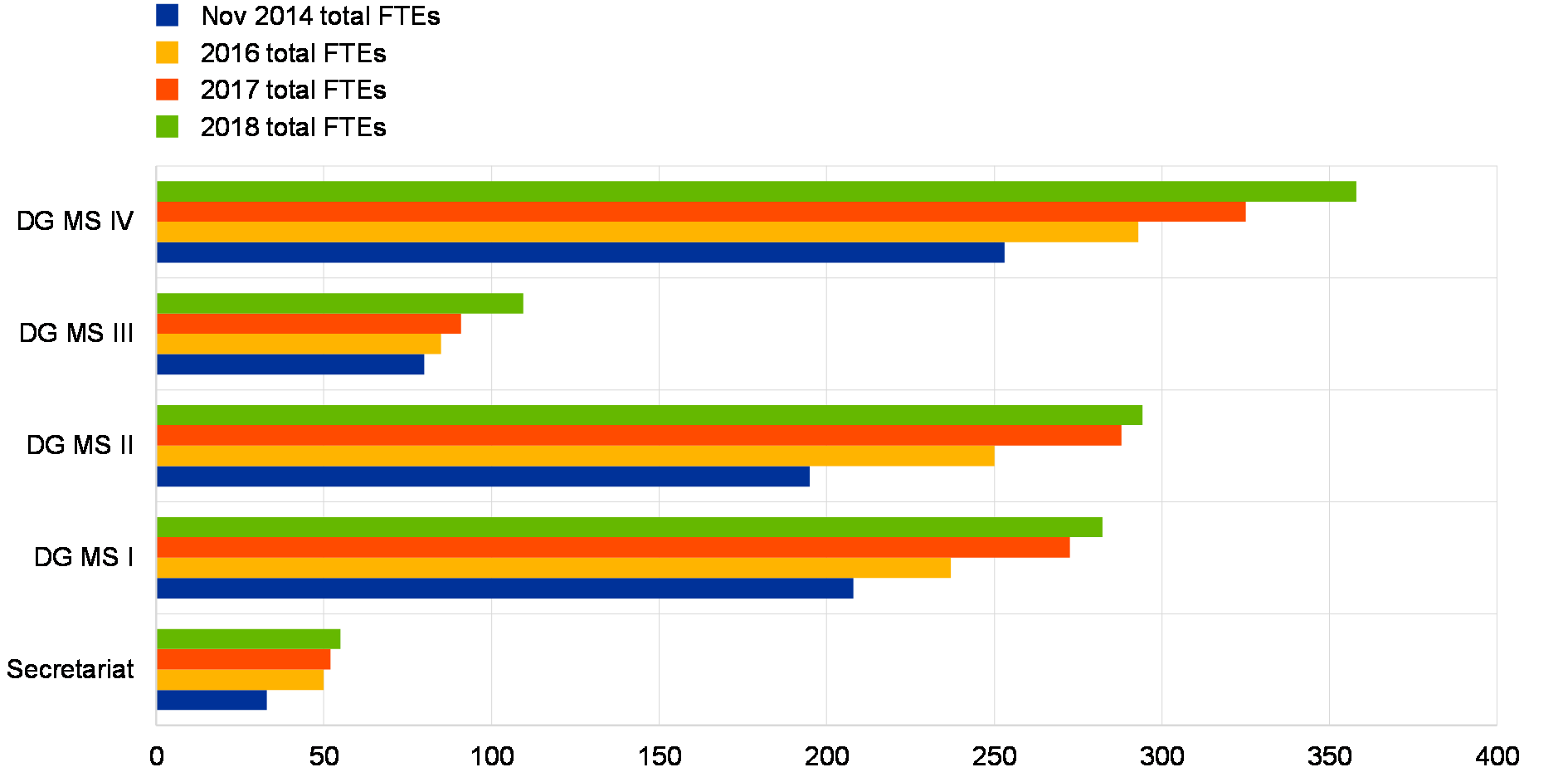

A total of 157 inspections were approved for 2017

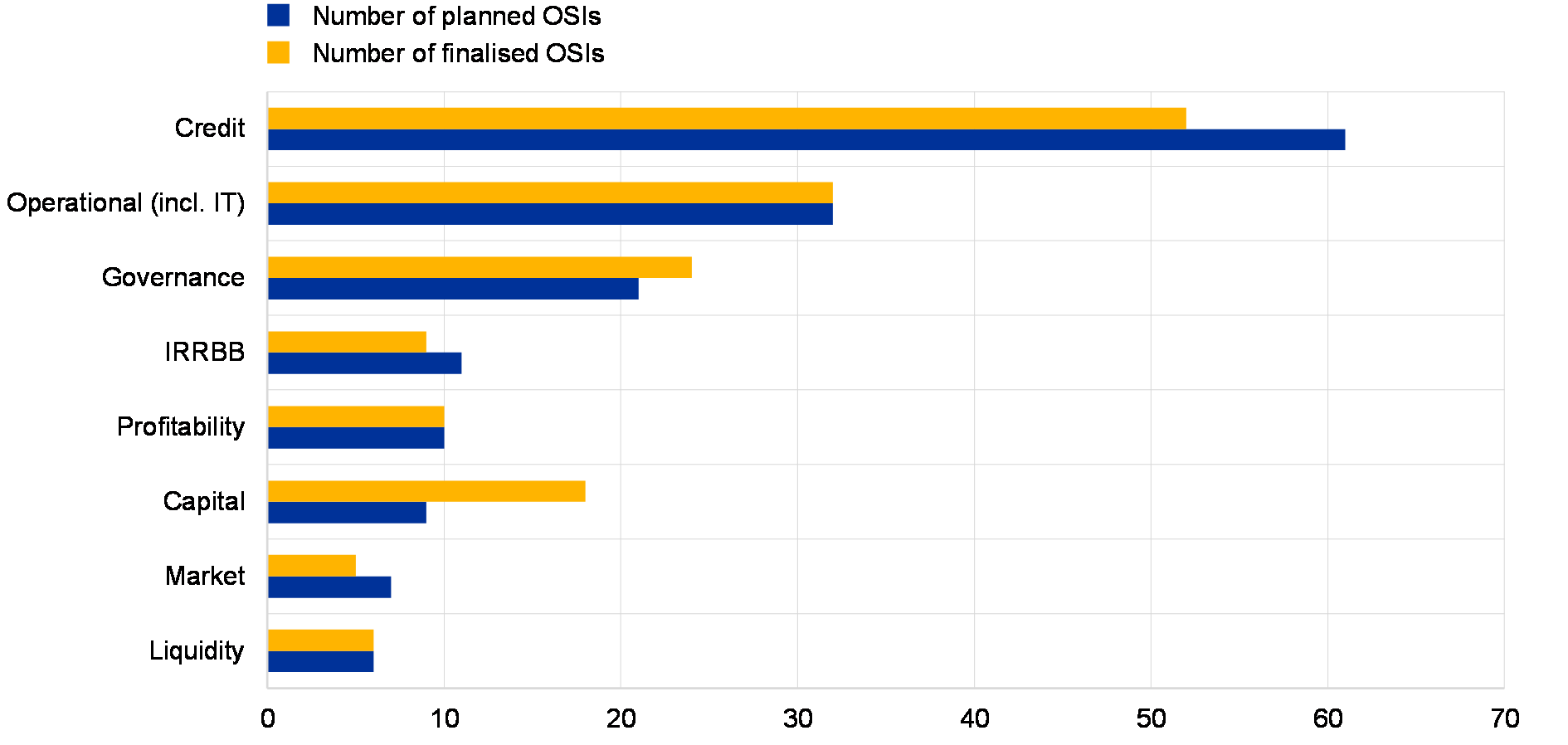

The third cycle of on-site inspections was part of the 2017 supervisory examination programme (SEP). A total of 157 inspections were approved for 2017 (compared with 185 in 2016). The drop in planned on-site inspections (OSIs) compared with 2016 resulted from the prioritisation of TRIM investigations and from a shift to more complex and time-consuming on-site inspections, in particular credit risk inspections.[21]

As at 31 December 2017, all but one of the planned OSIs (156 out of 157) had been launched. Of these, 64 inspections were completed in 2017 and the final reports shared with the inspected institutions. The overall number of OSIs finalised in 2017 also includes 98 inspections carried out as part of the 2016 on-site SEP programme, which were started in 2016 and finalised in 2017, as well as 18 OSIs outside the SSM countries.

Chart 6

2017 on-site inspections: breakdown by risk type

Notes: In the course of 2017, inspections from both the 2016 and 2017 on-site SEP programmes were finalised. This explains why more capital inspections were finalised in 2017 than were included in the 2017 SEP.

On-site inspections are planned and staffed in close cooperation with the NCAs, which continue to provide most of the heads of mission and team members. As at 31 December 2017, 90% of the inspections had been led by the NCAs, with a focus mainly on groups that are headquartered in the NCAs’ respective countries. The remaining 10% of the inspections were led by the ECB’s Centralised On-site Inspections Division (COI).

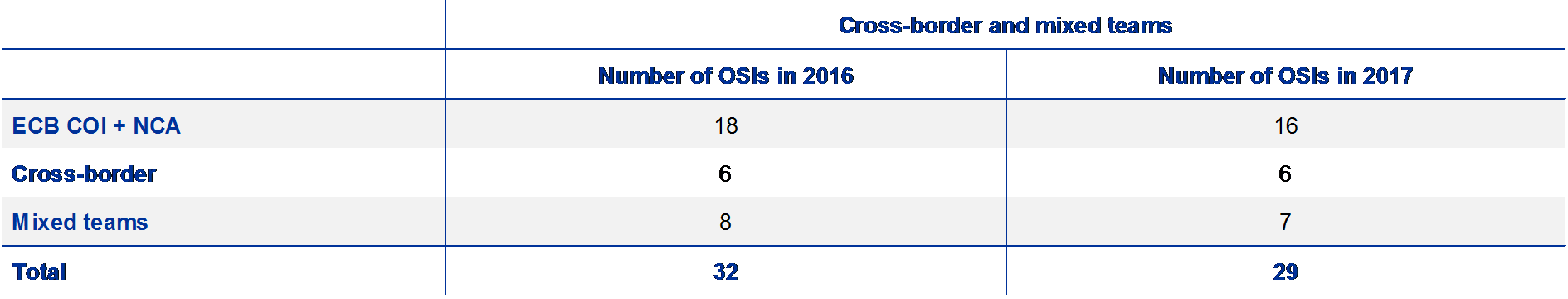

In 2017 European banking supervision launched a system-wide approach to increase the number of cross-border and mixed-team inspections in the coming years

In 2017 European banking supervision launched a fully-fledged system-wide approach with the objective of increasing the number of cross-border and mixed-team inspections in the coming years. To this end, a more precise definition of mixed/cross-border teams was introduced and an action plan devised by the ECB’s Supervisory Board. Teams are considered to be “cross-border” when the head of mission and at least one team member do not come from the relevant home/host NCA. A team is considered to be “mixed” when the head of mission comes from the relevant home/host NCA, while at least two team members do not come from the relevant home/host NCA.

Applying this new definition, 29 of the 157 OSIs planned for 2017 (18.5%) were staffed by mixed/cross-border teams, representing a slight drop when compared with 2016. The implementation of the new action plan is expected to reverse this trend: in 2018, about 25% of planned OSIs will be carried out by mixed/cross-border teams.

Table 2

Staffing of inspections: NCA vs ECB

After more than two years of experience, the ECB’s Supervisory Board decided to amend the end-to-end[22] process for on-site inspections. These modifications aimed to improve the overall quality, speed and accountability of the inspections. Banks now have the possibility to comment on the findings in writing in an annex to the inspection report. This revised process allows for full transparency and ensures that the relevant JST can take the bank’s comments into consideration when preparing the follow-up to the inspection.

In July 2017 the ECB issued a guide on on-site inspections and internal model investigations for public consultation

In July 2017 the ECB issued a guide on on-site inspections and internal model investigations for public consultation. The objective of the guide is to explain how ECB Banking Supervision conducts OSIs and to provide a useful reference for inspected banks. The draft guide is currently being revised and will be issued following the ECB’s Supervisory Board’s approval and the Governing Council non-objection procedure.

For 2018, several inspections that cover virtually identical topics will be aligned in scope and timing. This will allow for an intensified discussion between the heads of mission and the ECB’s monitoring teams. The aim is to further improve the efficiency of the inspections and the consistency of the approach.

Key findings from on-site inspections

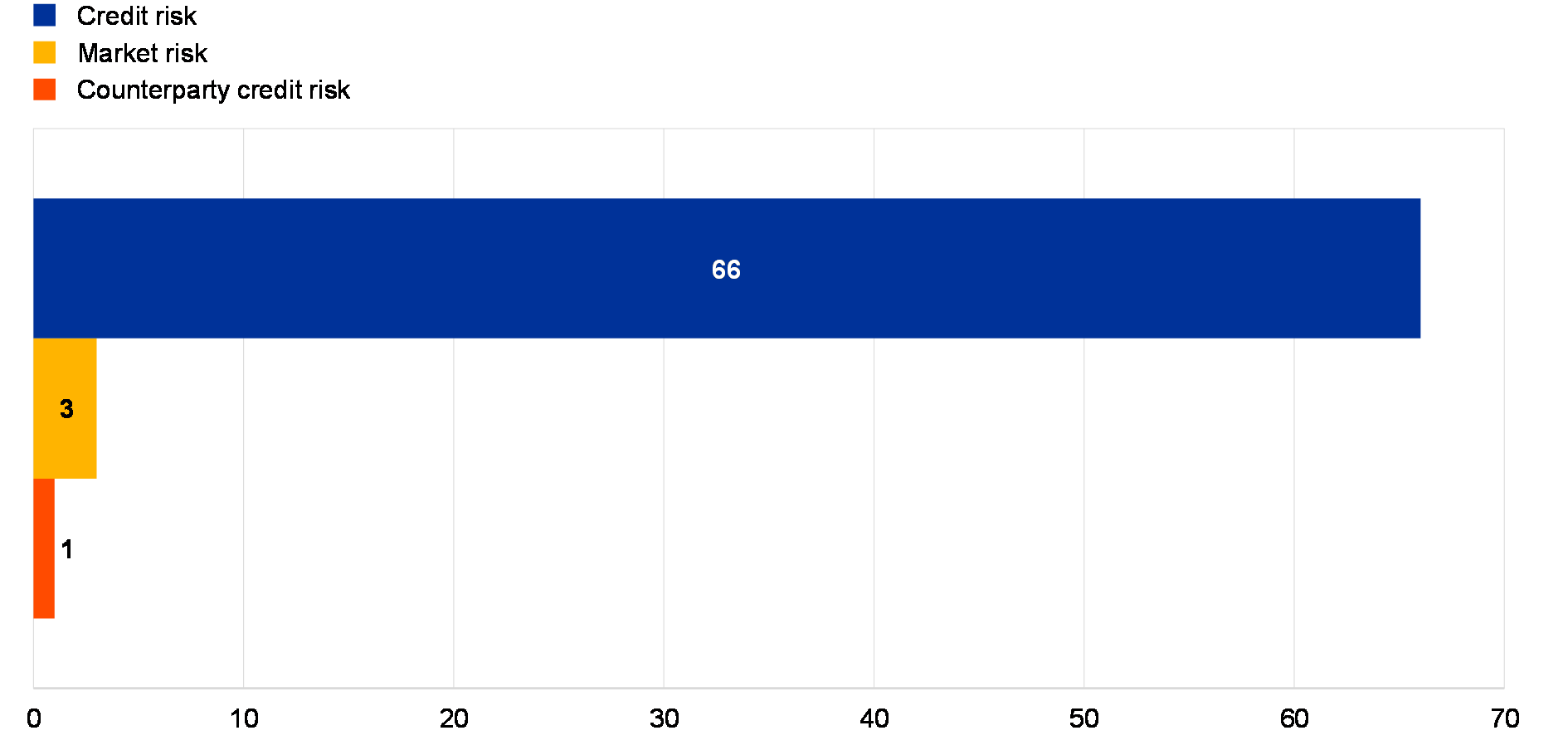

The following analysis covers eight risk categories and 137 inspections in respect of which the on-site inspection report was released between 1 January and 31 October 2017.

Credit risk

More than half of the credit risk inspections focused exclusively on the qualitative aspects of the credit risk management process. The remaining 45% targeted the quality of the assets by performing credit file reviews, and revealed financial impacts in excess of €10 billion. In more detail, the most critical findings were:

- Inappropriate classification of debtors: shortcomings in the definition and/or identification of default or non-performing exposures, weak processes for monitoring high-risk borrowers (early warning system, forbearance identification, internal ratings). As a result, there is a need for additional provisions.

- Miscalculation of provisions: collateral haircuts, time to recovery, cure rates, cash flow estimates, and collective provisioning parameters.

- Weak credit-granting processes: inadequate debtor analysis, unidentified exceptions to the bank’s delegation/limit system.

- Governance issues: deficiencies in the internal control “three lines of defence” model, e.g. weak second line of defence: weak risk management function, lack of involvement of the board or top managers, insufficient power of internal audit functions, over-centralisation of the decision-making process.

- Regulatory ratios: miscalculation of risk-weighted assets, breaches of large exposure regulations.

Governance risk