- SPEECH

Evidence-based supervision: addressing evolving risks, maintaining resilience

Keynote speech by Claudia Buch, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, at the Banking Supervision Research Conference 2025 on “Technological innovations in financial markets – Risks and opportunities in banking and regulation”

Frankfurt am Main, 9 December 2025

Welcome to this year’s Banking Supervision Research Conference.[1] Last summer, when I spoke to this group, I talked about the “risk assessment paradox”. Many analytical tools rely on past data. So at the precise moment when forward-looking risk assessments are needed to cut through uncertainty and identify emerging vulnerabilities, these tools may become less useful. This does not mean that we should stop doing analytical work. Quite the contrary: this is the time when we need to use a range of analytical approaches, compare results provided by different models, and apply judgement to draw lessons from the outcomes.

These considerations have, if anything, become more relevant over the past year, as some of the trends I described last summer have since intensified.

Some geopolitical risk scenarios that were fairly abstract last year have materialised in the meantime. Trade policy uncertainty has significantly increased with, so far, a relatively limited impact on credit losses and provisioning needs. However, the longer-term effects on banks may only unfold over time.[2] Cyberattacks have increased in intensity and severity over the past few years, and these are a key concern for the risk management of many banks. Therefore, in September last year, we published a framework that can be used to analyse the impact of geopolitical risks on banks.[3]

Competitive pressure through non-bank financial intermediaries and issuers of crypto-assets such as stablecoins has increased. Some lending activity has shifted to providers of private credit – often outside of the regulatory perimeter, but with significant links to banks and with limited visibility for banks’ risk management and supervisors.[4] Generally, the changing patterns of competition and developments in the provision of financial services can have positive welfare effects. Nevertheless, regulators and supervisors need to remain vigilant to emerging financial stability risks, liquidity mismatches and pockets of heightened leverage.[5] Banks need to monitor associated risks well and invest in the resilience of their IT infrastructures.

How to promote growth and competitiveness is certainly a discussion that has become more prominent. Some argue that relaxing banking regulation or supervision could unleash productivity and growth. I am strongly convinced that deregulation and “de-supervision” are not the right paths to take. It would only weaken resilience at a time when it is needed the most. Resilience and growth are two sides of the same coin.

We are responding to these developments in two ways.

First, we have supervisory priorities that focus on banks’ resilience (Figure 1).[6] We have a dedicated work programme centred on banks’ resilience to geopolitical risks and macro-financial uncertainties. We will, for example, gather evidence on banks’ underwriting standards as one way to assess future credit risks. The work programme also focuses on banks’ operational and IT resilience, with a specific emphasis on improving banks’ risk data aggregation capabilities. These capabilities are key to informed decision-making in an uncertain environment.

Figure 1: The ECB’s supervisory priorities for 2026-28

Source: ECB.

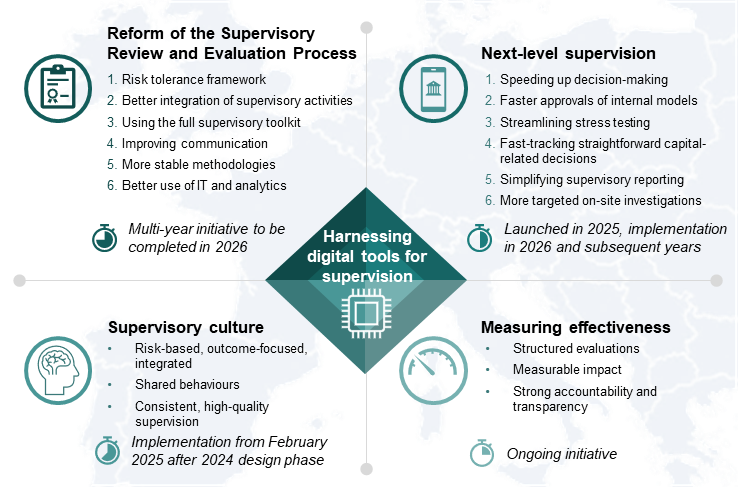

Second, we are improving the way we conduct supervision (Figure 2). Evolving risks, structural changes in the financial system and potential risk spillovers from less well-regulated parts of the financial system can have adverse implications for the banks we supervise. But to understand those implications, we cannot simply monitor standard financial indicators or extrapolate trends from the past. We need to create space to analyse the changes, and we are creating this space by becoming more efficient, effective and risk-based.

Figure 2: The ECB’s agenda for more efficient, effective and risk-based European banking supervision

Source: ECB.

When setting priorities and carrying out these reforms, we follow an evidence-based agenda. Starting from our objectives, we collect key indicators, we track their evolution over time, we monitor changes in our efficiency as we track the evolution of risks and resilience, and we assess our effectiveness. All of this is far from easy. It requires an infrastructure that supports evidence-based supervision and policy, and it requires good analytical frameworks.

In short, there is a large spectrum of projects in which supervisors and academics can benefit from an exchange of views. So let me go into more detail about what we do to stimulate discussions and encourage new ideas.

Forward-looking risk assessment amid high geopolitical uncertainty

Geopolitical risks and macro-financial uncertainties are undoubtedly heightened. Global trade tensions escalated sharply following the announcement of new tariffs in early 2025, triggering a rapid repricing in bond markets. The episode underscored how sensitive markets have become to geopolitical signals and how abruptly risk assessments and liquidity conditions can shift.

The impact on European banks has been benign so far. However, there are good reasons to believe that the full effect of higher tariffs and uncertainty has not yet materialised. The “risk assessment paradox” is very real. We must use different analytical tools to cut through the uncertainty and shed light on potential future developments.

This year’s stress test conducted by the European Banking Authority (EBA) has provided one important piece of information.[7] The adverse scenario was based on a macroeconomic scenario of escalating trade tensions, market disruptions and weaker growth. The results are encouraging in the sense that Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital depletion in the adverse scenario would be lower than in the 2023 stress test.

But this largely reflects higher profitability rather than lower underlying risk. Losses would in fact be higher than in the stress test two years ago, and the increase in non-performing loans would be greater. Hence, geopolitical risks are certainly not “benign” – they leave their mark on banks’ balance sheets. Higher profits cushion the impact of the losses, which explains why the capital depletion would be lower.

Moreover, the results differ across individual banks. A total of 24 banks would be subject to dividend restrictions automatically imposed by regulation in at least one year of the three-year projection horizon, as they would breach the maximum distributable amount trigger point in the adverse scenario.[8] Recent research drawing on the published 2025 stress test data shows that the impact of geopolitical tensions is higher for smaller and less diversified banks.[9]

Understanding such differences across banks is important from a supervisory perspective: the stress test results inform our bank-specific supervisory follow-up in terms of setting Pillar 2 capital guidance and deciding on qualitative measures, such as any improvements needed in banks’ risk management systems.

The EBA stress test applies a common adverse scenario to all banks, which then leads to different capital impacts across banks. This ensures comparability. But it also means that the scenario may be more severe for some banks than for others, so that the results may not reflect the most severe risk scenario individual banks need to prepare for.

Therefore, next year, we will take a complementary perspective.[10] We will “reverse” the assumptions: instead of using a common scenario, we will ask banks to conduct a stress test that leads to a common capital depletion. We will not impose restrictions on the geopolitical risk scenarios that can lead to such a depletion. Banks will use their internal tools for capital and liquidity planning,[11] and common data reporting requirements will be much leaner than for standard stress tests. At the same time, the reverse stress test will provide relevant information about banks’ preparedness to face geopolitical risks, their internal stress-testing capabilities and the scenarios that lead to large losses.

Apart from stress testing, banks have to address evolving risks through IFRS 9 overlays – adjustments to expected credit loss models to reflect risks not captured by historical data. Progress has been made, particularly on climate and environmental risks, but practices remain diverse.[12] Some banks still rely on generic “umbrella overlays” that do not differentiate between sectors, or they use standard, aggregate macroeconomic forecasts that they adjust for their purposes. Such approaches may underestimate the specific vulnerabilities of certain borrowers. Sound risk management requires more granular analysis and appropriate changes in the classification of loans when risks increase, rather than a general overlay. Nevertheless, when there is substantial uncertainty that is hard to model, ex post model overlays – if applied correctly – can be a good mitigant.

Geopolitical risk management is not the only challenge banks are currently facing. They also need a strategic response to the increasing presence of non-banks in the market for the provision of traditional banking services, including private credit and stablecoin issuance.

We need better visibility of the risks and vulnerabilities that are building up in this space, as traditional reporting does not capture some of the new developments. But, for the time being, we need to find our way using the patchy and incomplete map that we have until a global consensus on minimum reporting and transparency requirements has been reached and the relevant reporting standards have been implemented.[13]

Navigating unknown territory with an unreliable map requires innovative ideas – and academic work can partly fill the gap. We need conceptual and applied theoretical work to make sense of changing patterns in market structures, the drivers of entry and exit, the drivers of competitive advantage and the potential implications for risk-taking incentives and vulnerabilities. Academia has certainly made great strides in terms of rigorous empirical work, but at a time of deep structural change, empirical work naturally reaches its limit. This is why we need continuous interaction between building hypotheses, analysing incoming evidence and updating our priors.

Adapting supervision to the new environment: more efficient, effective and risk-based

Banks need strategic responses to the changing environment, as do supervisors. So let me quickly recap where we have come from and what the new challenges are.

The Single Supervisory Mechanism – a key pillar of the European banking union – celebrated its tenth anniversary last year. In the first years of European supervision, the priority was to build common processes and ensure consistency across jurisdictions. This was a necessary “start-up phase”.

In terms of risks and resilience, the task was relatively straightforward: reducing exposures to non-performing loans and building resilience. The global financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis had left deep scars on the balance sheets of many banks. In 2010, euro area banks’ median CET1 capital ratio was around 10%.[14] In 2015, the non-performing loan ratio was still around 10%, on average, but in some countries it was as high as 50%.[15]

So the task was to reduce banks’ exposures to non-performing loans and strengthen financial resilience. Today, the CET1 capital ratio is around 16%, while the non-performing loan ratio has fallen to around 2%.

Better resilience has come about thanks to strengthened regulation and supervision and better risk management by banks. But there is a third key factor that matters: policy support for households and firms. Even during the recent recessions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the energy crisis, loan losses did not increase, thanks to resilience in the real economy and substantial monetary and fiscal support.

Today, the challenges for banks are different. Banks need to identify potential future sources of risk in a highly uncertain environment. They need to ensure robust operational resilience, sound IT systems and effective protection against cyber risks. Scenario planning, stress testing and good governance have moved to the forefront.

Supervisors are facing a familiar challenge: how to remain forward-looking and create space to analyse and react to new developments. In recent years, European banking supervision has launched a reform agenda with three main objectives.

Enhancing efficiency. Supervisors need to assess the impact of the new environment on banks’ risks and risk controls while operating within fixed resource envelopes. Some procedures that served us well in a more stable environment may prevent us from focusing on key risks and vulnerabilities. Moreover, good supervision requires close interaction between Joint Supervisory Teams, which are the key contact point for banks, and on-site inspectors and horizontal functions analysing common trends across banks. This requires an integrated planning process, not least to avoid overlapping information requests.

Ensuring effectiveness. Effective supervision means identifying the root causes of banks’ weaknesses, communicating expectations clearly and escalating measures where banks’ remediation falls short.

Focusing on the risks that matter. Not every risk requires the same amount of supervisory attention. We have thus developed a risk tolerance framework and a multi-year approach that guides Joint Supervisory Teams in allocating resources based on banks’ risk profiles and business models.

These reforms have tangible benefits for all stakeholders by reducing compliance costs, strengthening our ability to deliver on our mandate while enhancing transparency and accountability, and improving our data infrastructures.

More specifically, the objectives of the reforms guide four concrete initiatives.

The first is the overhaul of the annual Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP), in which we assess banks’ risks and risk controls.[16] In 2023 we received recommendations from an independent expert group we had commissioned. In 2024 we decided on a reform agenda which is now well advanced and will be fully implemented next year. It is about taking a multi-year perspective during risk assessments, streamlining coordination across supervisory activities, strengthening the use of the full supervisory toolkit, delivering decisions earlier and communicating clearly with banks, stabilising methodologies, and making better use of IT systems and analytics.

The second initiative, “Next-level supervision”, was launched in 2025. This project applies the reform objectives to all major supervisory tasks, including authorisations, approvals of internal models, stress testing, reporting and on-site inspections. Across these reform elements, we use digital and suptech tools to focus resources and to create capacity to address evolving risks.

The third element is a supervisory culture initiative, which makes sure that the spirit of the reforms is embedded into everyday decision-making, both within the ECB and across the national competent authorities.

The fourth element of the reform agenda is about assessing the effectiveness of supervision and enhancing evidence-based supervision. This is where input from academia is most valuable. How can we measure supervisory effectiveness? What are the trade-offs between efficiency and resilience when streamlining processes? How can we assess whether our supervisory culture has evolved? And what are the implications for the banks – in terms of both the risks they face and their resilience? All these questions merit analytical answers and we would appreciate your ideas.

Improving the infrastructure for evidence-based supervision

Evidence-based supervision is, in my view, essential to maintaining a resilient financial system. But it is also essential to containing the forces pushing for deregulation and a loosening of standards with the supposed benefit of generating growth and promoting productivity.

Let me explain what I mean by “evidence-based supervision”. The legislator, and therefore the public, has given us a clear mandate – keeping banks safe and sound. This must be our starting point and the objective of our work.

We must, of course, deliver on our mandate in the most efficient and effective way, and we must ensure that banks are resilient, given the risks they take.

Selecting indicators – for capital, liquidity, business-model viability and the quality of governance – is thus the second step in our evidence-based supervisory cycle. We are also tracking progress made with the reforms I have described above – how quickly we issue decisions, how focused our supervision is, or how much data and information we request from banks.

The third step is to design and implement supervisory measures – from moral suasion to legally binding decisions, including enforcement measures, which are designed to compel banks to restore compliance with prudential requirements.

And finally, we need to evaluate outcomes – both intended and unintended – and feed the lessons back into the next round of supervisory measures and priority-setting. This process facilitates systematic learning.

This is, of course, a highly stylised supervisory cycle. We cannot conduct comprehensive evaluations for all the activities we perform, and we cannot exactly “measure” all relevant aspects of banks’ safety and soundness, which is why qualitative supervisory judgement remains indispensable. There are many qualitative factors shaping banks’ performance that cannot be precisely quantified; observable outcomes at bank level are shaped by many factors other than supervision.

This supervisory cycle structures our work and enhances transparency and accountability. It requires a sound infrastructure consisting of five elements.

Evaluation frameworks. Over the past decade, the Financial Stability Board and the Basel Committee have developed frameworks to evaluate the post-crisis financial sector reforms.[17] These frameworks combine quantitative indicators with qualitative assessments and enable potential unintended effects to be identified. Within European banking supervision, we are building on this work and integrating assessments of supervisory effectiveness into our reform agenda, making use of a “second line of defence” function that benchmarks supervisory actions across banks.

Repositories. There is a plethora of information and analytical work on supervision, regulation, and the impact on banks and the economy. However, this evidence is not easily accessible. Repositories and meta analyses pool this widely dispersed evidence into cumulative knowledge. The Bank for International Settlements’ Financial Regulation Assessment: Meta Exercise (FRAME) classifies empirical studies on the effects of capital and liquidity regulation and on the too-big-to-fail reforms.[18] The results of this work are encouraging: the benefits of the post-crisis reforms clearly outweigh their costs, and better-capitalised banks support credit provision over the long run.[19]

Extending FRAME to other key policy issues would be the natural next step. There are many studies on bank efficiency and competitiveness, as well as their drivers, but, again, this evidence is patchy and often not easily accessible for policy work.

Certainly, building and maintaining repositories can be resource-intensive, but artificial intelligence offers new opportunities. Natural language processing can automate the identification and classification of studies. Within ECB Banking Supervision, we are developing “Athena”, an AI-enabled tool that supports textual analysis and translation, allowing us to process large volumes of documents. Alongside this, we are setting up a virtual lab to consolidate methodologies and facilitate code sharing.

Data centres. Good policy analysis requires consistent and well-documented data. The ECB has launched a pilot project to grant external researchers access to anonymised bank-level data.[20] Access to these data is organised in close cooperation with national central banks and statistical offices. This pilot can pave the way towards a permanent research infrastructure. Within ECB Banking Supervision, the single data lake – Agora – integrates large volumes of structured data into one system, improving efficiency and consistency. Clear governance of access rights and data protection is essential, of course.

Innovation. Innovation in modelling can help overcome data constraints and support the analysis of evolving risks. Within the ECB, we are using different suptech tools, such as network analysis software (“Navi”) to map institutional interlinkages or stress-testing platforms (“Gabi”), to optimise models at scale. In practice, Gabi can generate and refine large numbers of regression models simultaneously. Navi produces network diagrams that visualise complex ownership structures and interdependencies, combining information from multiple sources to give a clearer overview of relationships within banking groups. Tools of this kind support more structured analysis and help us test the robustness of our assessments, while also facilitating cooperation with academics and other authorities.

Dialogue. Dialogue between researchers and policymakers is crucial. Policymakers are often faced with urgent issues but lack the time and data to conduct detailed analyses. Researchers have the analytical tools and methods to provide evidence, but incentive structures in academia may not reward work on policy-relevant questions or the replication of earlier studies – both of which are so crucial for policy work. To facilitate dialogue, we need conferences like this one as well as structured network building. Our participation in initiatives such as the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Industrial Doctoral Network on Digital Finance is one element of this. ECB Banking Supervision’s involvement includes hosting six doctoral candidates for 12 months. These researchers will work with our suptech team on various research topics related to digital finance.

Together, these five pillars form the foundation for evidence-based supervision. They embed rigour and accountability into the policy process itself. And they provide the analytical basis for our reform agenda.

The role of evidence in safeguarding resilience

Evidence-based supervision is a safeguard against complacency. Periods of calm can create pressure to simplify or relax rules in ways that erode resilience over time. Following a clear policy and supervisory cycle allows us to identify effects and potential unintended side effects of regulation and supervision. Decisions to modify rules should be based on sound empirical evidence rather than anecdotal evidence. They need to take confounding factors and general equilibrium effects into account.

Of course, analytically sound evaluations take time. But we do have that time. Empirical evidence to date shows that stronger capital and liquidity requirements have not constrained lending in the long run but have rather supported sustainable credit growth and resilience. This strengthens the case for maintaining robust regulatory and supervisory standards while improving implementation and addressing evolving risks.

Looking ahead, our focus is on turning this agenda into day-to-day practice. Next year, reforms of European banking supervision will be fully implemented, and we will report on the progress achieved in the annual reports on the ECB’s supervisory activities. We will further develop the infrastructure for evaluating supervision and regulation. This includes expanding repositories, strengthening evaluation frameworks, improving data access and availability, and deepening cooperation with academia and other authorities.

Without that, there is a clear risk that efforts to “simplify” regulation and supervision in the end lead to deregulation and de-supervision. Together, we can mitigate this risk. The resilience built over the past decade is a public good. It should be protected, not traded for short-term convenience.

I am grateful to Korbinian Ibel, Thomas Jorgensen, and John Roche for their comments and support in preparing this speech. All errors and inaccuracies are my own.

Avril, P., Bochmann, P., Fahr, S., Horan, A., Pancaro, C. and Pizzeghello, R. (2025), “Risks to euro area financial stability from trade tensions”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, May.

See the ECB’s banking supervision website, “Addressing the impact of geopolitical risk”.

Buch, C. (2025), “Hidden leverage and blind spots: addressing banks’ exposures to private market funds”, The Supervision Blog, ECB, 3 June.

ECB (2025), Financial Stability Review, November.

See the ECB’s banking supervision website, “ECB Supervisory Priorities 2026-28”.

ECB (2025), “Stress test shows that euro area banking sector is resilient against severe economic downturn scenario”, press release, 1 August; ECB (2025), 2025 stress test of euro area banks – Final results, August.

Under Article 141 of the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD), institutions that fall below their combined buffer requirement breach the “MDA trigger point”. Once this trigger is breached, automatic restrictions on distributions apply – covering dividends, variable remuneration and AT1 coupons – with the MDA determining the ceiling on such distributions.

Haselmann, R., Heider, F., Kaiser, L.E., Schlegel, J. and Tröger, T. (2025), “The Impact of Geopolitical Risks on the Resilience of Banks in the Banking Union”, In-depth analysis requested by the ECON Committee, European Parliament, November.

Buch, C. (2025), “Stress tests in uncertain times: assessing banks’ resilience to external shocks”, The Supervision Blog, ECB, 5 September.

More specifically, they can draw on their internal capital adequacy assessment process (ICAAP)

ECB (2024), IFRS 9 overlays and model improvements for novel risks – Identifying best practices for capturing novel risks in loan loss provisions, July.

European Systemic Risk Board (2024), A system-wide approach to macroprudential policy – ESRB response to the European Commission’s consultation assessing the adequacy of macroprudential policies for nonbank financial intermediation, November; Financial Stability Board (2025), Leverage in Nonbank Financial Intermediation: Final report, 9 July.

See Chart 28 in ECB (2025), “Financial integration indicators”, Financial integration and structure in the euro area – Statistical annex, November.

See Chart 23 in ECB (2025), “Financial integration indicators”, Financial integration and structure in the euro area – Statistical annex, November.

Buch, C. (2024), “Reforming the SREP: an important milestone towards more efficient and effective supervision in a new risk environment”, The Supervision Blog, ECB, 28 May.

Thedéen, E. (2025), “Resilience pays: the strategic value of regulation and supervision”, speech at the Eurofi Financial Forum, Copenhagen, 19 September; Financial Stability Board (2017), Framework for Post-Implementation Evaluation of the Effects of the G20 Financial Regulatory Reforms – Technical Appendix, 3 July; Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2022), Evaluation of the impact and efficacy of the Basel III reforms, 14 December.

Bank for International Settlements, Financial Regulation Assessment: Meta Exercise.

Boissay, F., Cantú, C., Claessens, S. and Villegas, A. (2019), “Impact of financial regulations: insights from an online repository of studies”, BIS Quarterly Review, March.

ECB, “Pilot project for research access to confidential statistical data”.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts